by Seth Tobocman | October 31, 2019

Peter Kuper is a first rate comic book artist and a master stylist who has, over the years, adapted many classic works of literature to graphic format, including Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and numerous works by Franz Kafka. But adapting Joseph Conrad’s Heart Of Darkness may prove to be his most difficult assignment.

Title: Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

Words by: Joseph Conrad and Peter Kuper

Art by: Peter Kuper

Foreword by: Maya Jasanoff

Published by: W. W. Norton & Company (1st edition)

Pages: 160

Additional Specs: Hardcover, 6.5″ x 9.4″, $21.95 USD

When I was in grade school there was a big controversy over Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. Parents wanted it removed from the curriculum because they felt it would encourage racist attitudes. The author would have certainly turned over in his grave. Twain was an abolitionist and most of the book concerns the attempt of a character called “N***** Jim” to escape slavery. And there’s the rub, of course. The n-word is all over that book. And just preventing kids from picking up the habit of using that word is good enough reason to keep them from reading it until they are old enough to understand the historical context. The good intentions of the author aren’t enough to transcend the prejudices of his era. The same could be said about many other books of the past, such as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery melodrama, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. And I’m afraid Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness falls easily into this category.

The n-word is all over that book. And just preventing kids from picking up the habit of using that word is good enough reason to keep them from reading it until they are old enough to understand the historical context. The good intentions of the author aren’t enough to transcend the prejudices of his era. The same could be said about many other books of the past, such as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery melodrama, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. And I’m afraid Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness falls easily into this category.

The Heart Of Darkness tells of a journey up an unnamed stretch of African river, but it is obvious, both from details of the story and from details of Conrad’s own, 6 month service in Africa, that this story takes place in ‘The Belgian Congo’. A colony in which local people were being forced to harvest ivory, and later rubber, at gunpoint.

By the time that Conrad was writing this novel, slavery had been abolished in the United States and Europe. There was a broad European consensus that slavery was wrong. What will seem odd to us, however, is that Europeans, of that time, did not see any connection between slavery and racist ideology. Nor any connection. between slavery and colonialism. While European governments knew exactly what they were doing, they had sold the public a fairy tale, that in conquering Africa and South America, the white man was on a civilizing mission. Bringing the ‘savages’ railroads, modern medicine and Christian morality. In fact, people were told that colonial forces were protecting Africans from ‘the Arab slave trade’. So what is revealed in The Heart Of Darkness must have been quite shocking to that public.

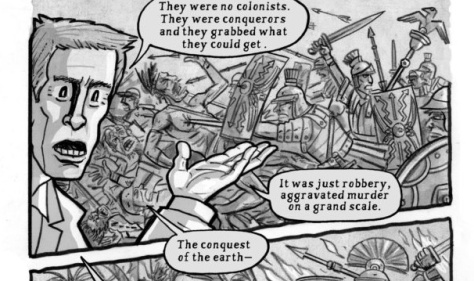

Conrad clearly intended the book to be an attack on European colonialism. He starts out by comparing the conquest of Africa to the Roman invasion of Briton, a reference which surely hit home with an English audience schooled in ancient history. He portrays the colonial administration as driven by greed, incompetent, cruel and cowardly. The author accurately describes how Africans were being worked to death in chains by their colonial masters. His wild depictions of colonial agents living like kings, displaying the shrunken heads of their enemies and taking black women as concubines are all factually based. In showing the high mortality rate of Europeans due to disease, he is no less truthful. He makes Africa sound like a horrible place that no sane European would want to go to.

Conrad details numerous atrocities committed against the Africans. But it is in his description of those Africans that the author’s prejudices become apparent. To start with, that ‘n-word’ is on every fifth page. But it gets worse. While he is quite frank about the fact that Africans are being enslaved beaten, starved and shot, he can’t seem to produce an African character who is a fully formed human being. To Conrad, Africans are monstrous and weird. ‘Savages’, with all the supernatural qualities that word ‘savage’ held for the Europeans of his generation. When he occasionally shows us an African who is using any type of machinery, he always points out the incompetence of that individual, as though there are certain tasks only white people were born to perform. There is just no way around it! This is a racist book.

So there is a lot of work to do before this story can be read by a contemporary audience. And Peter, always a hard worker, does it. The n-word is no where in this book. Most of the descriptions of Africans beguiled and confused by technology are also left out. And Peter draws the black characters beautifully and carefully. A great student of the history of cartooning, Kuper takes pains to avoid the type of racial caricature frequent in all but the most recent comic books.

African authors have criticized Conrad for comparing their continent to a blank space on the map, dark, mysterious, uncivilized and empty. A wild place waiting to be tamed. They remind us that Africa was home to a complex society before the colonial invasion. There are many places in the book where the settlers are firing at an unseen enemy. Shooting into the mist or into dense jungle. The comic artist tries to remedy this by re-staging these scenes so that we can see what the white characters cannot see. The people running from their bullets.

Kuper, who has travelled in Africa extensively, draws the African landscape beautifully. Combining a knowledge of specific detail with an eye for economy that he has picked up as an illustrator. There are panels of this book that I could stare at for hours.

But with all this good work, and with Conrad’s racist superstructure remodeled, Kuper cannot escape the underlying architecture of the book, its plot.

Marlow, Conrads’ protagonist, is sent upriver, on a mission to bring back Kurtz, a charismatic colonial agent, who has ‘gone native’ and begun to use ‘unorthodox methods’ such as murder, and collecting shrunken heads, to extract ivory from the local population. While the colonial administration appreciates the ivory, they don’t approve of what Kurtz does to get it. Although it is often implied that their real motive for taking out Kurtz may simply be jealousy of his success. Marlow is horrified by Kurtz’ brutality toward the Africans, but he none the less admires the man, and promises not to damage his reputation. When Marlow returns to England, he cannot bear to tell Kurtz’ fiancé what her beloved was engaged in.

While it’s a good yarn, the message of this narrative is politically problematic. It gives us the impression that the abuses of colonial rule were the result of individual men, driven mad by the difficulties of living in the bush, taking the matters into their own hands. And so European governments, and white society, remain innocent. We know that the opposite is the case. The Belgian government provided colonial agents with printed manuals, explaining how to force Africans to work for them, by taking their wives as hostages.

In his defense, Conrad may not have known this. Or he may have known, but correctly calculated, that his readers would not have believed such a thing.

This contradictory narrative, that describes the horror while exonerating the people most responsible for it, is precisely why The Heart Of Darkness was the perfect template for the Vietnam War film Apocalypse Now. Because this was exactly what we wanted to believe about Viet Nam. That the soldiers who massacred villagers at Mi Lai were good boys, driven crazy by war, and not cold blooded killers enacting a policy designed in Washington.

The story creates an impossible conundrum for Kuper. If he were to change the plot line of the book, then it would not be the same book at all. It would be a new novel and not an adaptation. Kuper stays on-mission, and maintains the story. So the book remains problematic, and maybe that is as it should be.

What, then, is the function of The Heart Of Darkness, be it in graphic novel form or not, for a contemporary audience?

It certainly is not a book about Africans, because Conrad seems to know less than nothing about them. It really is not a very good book about colonialism, because Conrad’s revelations are partial, at best. But it tells us a lot about the mindset of Europeans of that time. It shows us that while they were enthusiastic about colonizing the world, many were shocked when they discovered the methods necessary to accomplish that task. And it shows that when confronted with the truth, they often had trouble processing the information. ‘Denial’ then, is more than a river in Egypt, it is also a river in the Congo.

Today, The Heart Of Darkness, is a book about whiteness. I recommend both Conrad’s original text, and Kupers’ adaptation, to those studying this subject. I’m old enough to remember a world where school teachers assigned students to read books by Joseph Conrad, but told us that reading comics would lead to illiteracy. (They also told us that “The Beatles aren’t music!”) To live, today, in a time in which we must ask ourselves,” Is The Heart Of Darkness good enough to be turned into a graphic novel?” is indeed a delicious irony!

The style and colours in this book made a tremendous impact on me, and I had to read it through several times in order to appreciate the depth of the details and nuance. I enjoyed the ongoing transformation of masks throughout, the tattoo motif, the circle series, and the repetitive use of smoke and fragmentation. I also found the variety of panels and page layouts to be engaging, and I really appreciated the break from tradition western aspects and transitions. The layering of Aboriginal and pop-culture iconography was beautifully done, and the balance created through the imagery made it easily understandable despite my limited understanding certain cultural motifs. The result is a fast paced, engaging, and visually appealing experience.

The style and colours in this book made a tremendous impact on me, and I had to read it through several times in order to appreciate the depth of the details and nuance. I enjoyed the ongoing transformation of masks throughout, the tattoo motif, the circle series, and the repetitive use of smoke and fragmentation. I also found the variety of panels and page layouts to be engaging, and I really appreciated the break from tradition western aspects and transitions. The layering of Aboriginal and pop-culture iconography was beautifully done, and the balance created through the imagery made it easily understandable despite my limited understanding certain cultural motifs. The result is a fast paced, engaging, and visually appealing experience.

I had co-authors for all the science titles but one. I did the math books myself and found them tough going, because I’m so far removed from the classroom. My collaborators, being teachers, all had a good sense of what students find easy and hard, whereas I felt myself groping straight through. And the collaborations, despite occasional struggles, have always been a great experience for me. I learn a lot, and I like to think that my relentless cross-examination can lead the scientists to a little rethinking, too.

I had co-authors for all the science titles but one. I did the math books myself and found them tough going, because I’m so far removed from the classroom. My collaborators, being teachers, all had a good sense of what students find easy and hard, whereas I felt myself groping straight through. And the collaborations, despite occasional struggles, have always been a great experience for me. I learn a lot, and I like to think that my relentless cross-examination can lead the scientists to a little rethinking, too.