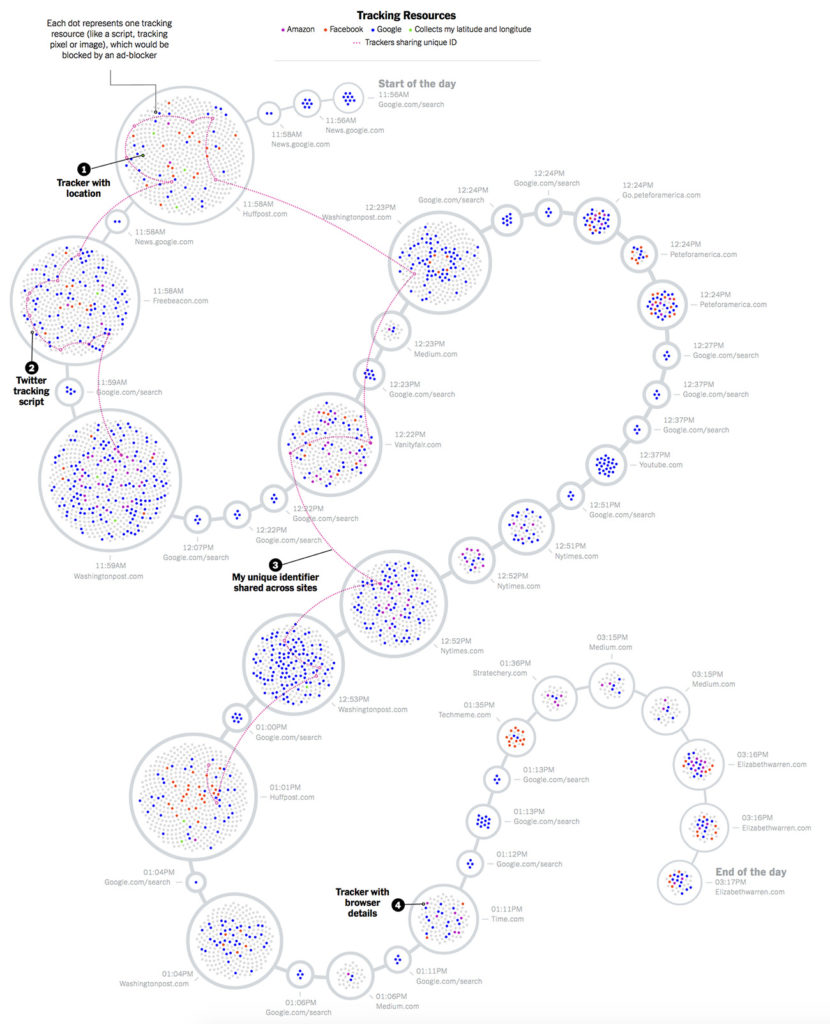

Farhad Manjoo, in the New York Times, ran an experiment on themself:

Earlier this year, an editor working on The Times’s Privacy Project asked me whether I’d be interested in having all my digital activity tracked, examined in meticulous detail and then published — you know, for journalism…I had to install a version of the Firefox web browser that was created by privacy researchers to monitor how websites track users’ data. For several days this spring, I lived my life through this Invasive Firefox, which logged every site I visited, all the advertising tracking servers that were watching my surfing and all the data they obtained. Then I uploaded the data to my colleagues at The Times, who reconstructed my web sessions into the gloriously invasive picture of my digital life you see here. (The project brought us all very close; among other things, they could see my physical location and my passwords, which I’ve since changed.)

What did we find? The big story is as you’d expect: that everything you do online is logged in obscene detail, that you have no privacy. And yet, even expecting this, I was bowled over by the scale and detail of the tracking; even for short stints on the web, when I logged into Invasive Firefox just to check facts and catch up on the news, the amount of information collected about my endeavors was staggering.

Here is a shrunk-down version of the graphic that resulted (click it to see the whole thing on the New York Times site):

Notably — at least from my perspective! — Stratechery is on the graphic:

Wow, it sure looks like I am up to some devious behavior! I guess it is all of the advertising trackers on my site which doesn’t have any advertising…or perhaps Manjoo, as seems to so often be the case with privacy scare pieces, has overstated their case by a massive degree.

Stratechery “Trackers”

The narrow problem with Manjoo’s piece is a definitional one. This is what it says at the top of the graphic:

This strikes me as an overly broad definition of tracking; as best I can tell, Manjoo and their team counted every single script, image, or cookie that was loaded from a 3rd-party domain, no matter its function.

Consider Stratechery: the page in question, given the timeframe of Manjoo’s research and the apparent link from Techmeme, is probably The First Post-iPhone Keynote. On that page I count 31 scripts, images, fonts, and XMLHttpRequests (XHR for short, which can be used to set or update cookies) that were loaded from a 3rd-party domain.1 The sources are as follows (in decreasing number by 3rd-party service):

- Stripe (11 images, 5 JavaScript files, 2 XHRs)

- Typekit (1 image, 1 JavaScript file, 5 fonts)

- Cloudfront (3 JavaScript files)

- New Relic (2 JavaScript files)

- Google (1 image, 1 JavaScript file)

- WordPress.com (1 JavaScript file)

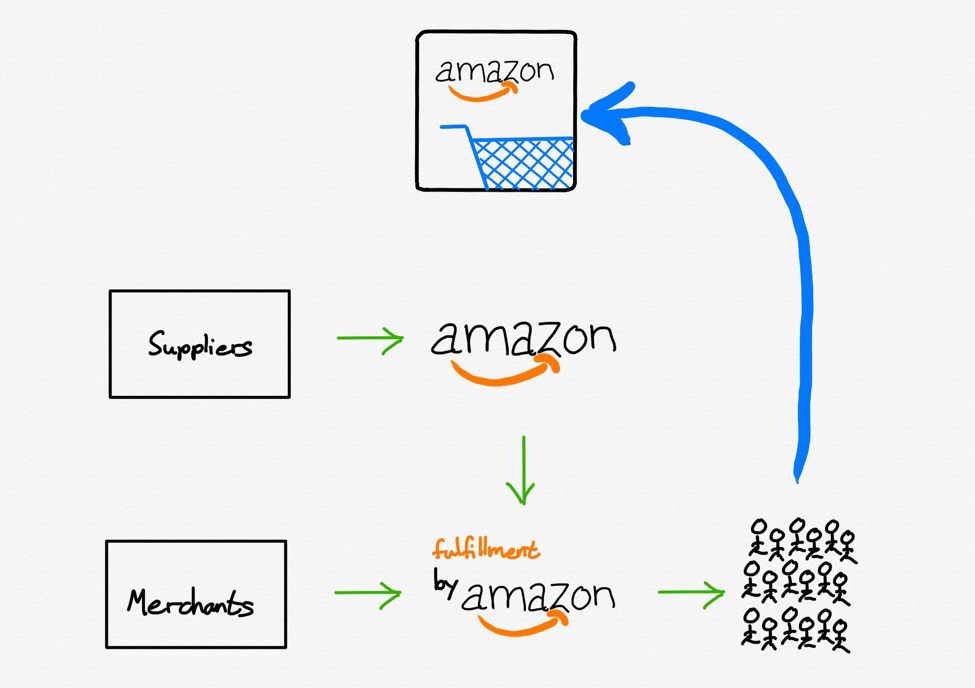

You may notice that, in contrast to the graphic, there is nothing from Amazon specifically. There is Cloudfront, which is a content delivery service offered by Amazon Web Services, but suggesting that Stratechery includes trackers from Amazon because I rely on AWS is ridiculous. In the case of Cloudfront, one JavaScript file is from Memberful, my subscription management service, and the other two are public JavaScript libraries used on countless sites on the Internet (jQuery and Pmrpc). As for the rest:

- Stripe is the payment processor for Stratechery memberships.

- Typekit is Adobe’s web-font service (Stratechery uses Freight Sans Pro).

- New Relic is an analytics package used to diagnose website issues and improve performance.

- Google is Google Analytics, which I use for counting page views and conversions to free and paid subscribers (this last bit is mostly theoretical; Memberful integrates with Google Analytics, but I haven’t run any campaigns — Stratechery relies on word-of-mouth).

- WordPress.com is for the Jetpack service from Automattic, which I use for site monitoring, security, and backups, as well as the recommended article carousel under each article.

The only service here remotely connected to advertising is Google Analytics, but I have chosen to not share that information with Google (there is no need because I don’t need access to Google’s advertising tools); the truth is that all of these “trackers” make Stratechery possible.2

The Internet’s Nature

This narrow critique of Manjoo’s article — wrongly characterizing multiple resources as “trackers” — gets at a broader philosophical shortcoming: technology can be used for both good things and bad things, but in the haste to highlight the bad, it is easy to be oblivious to the good. Manjoo, for example, works for the New York Times, which makes most of its revenue from subscriptions;3 given that, I’m going to assume they do not object to my including 3rd-party resources on Stratechery that support my own subscription business?

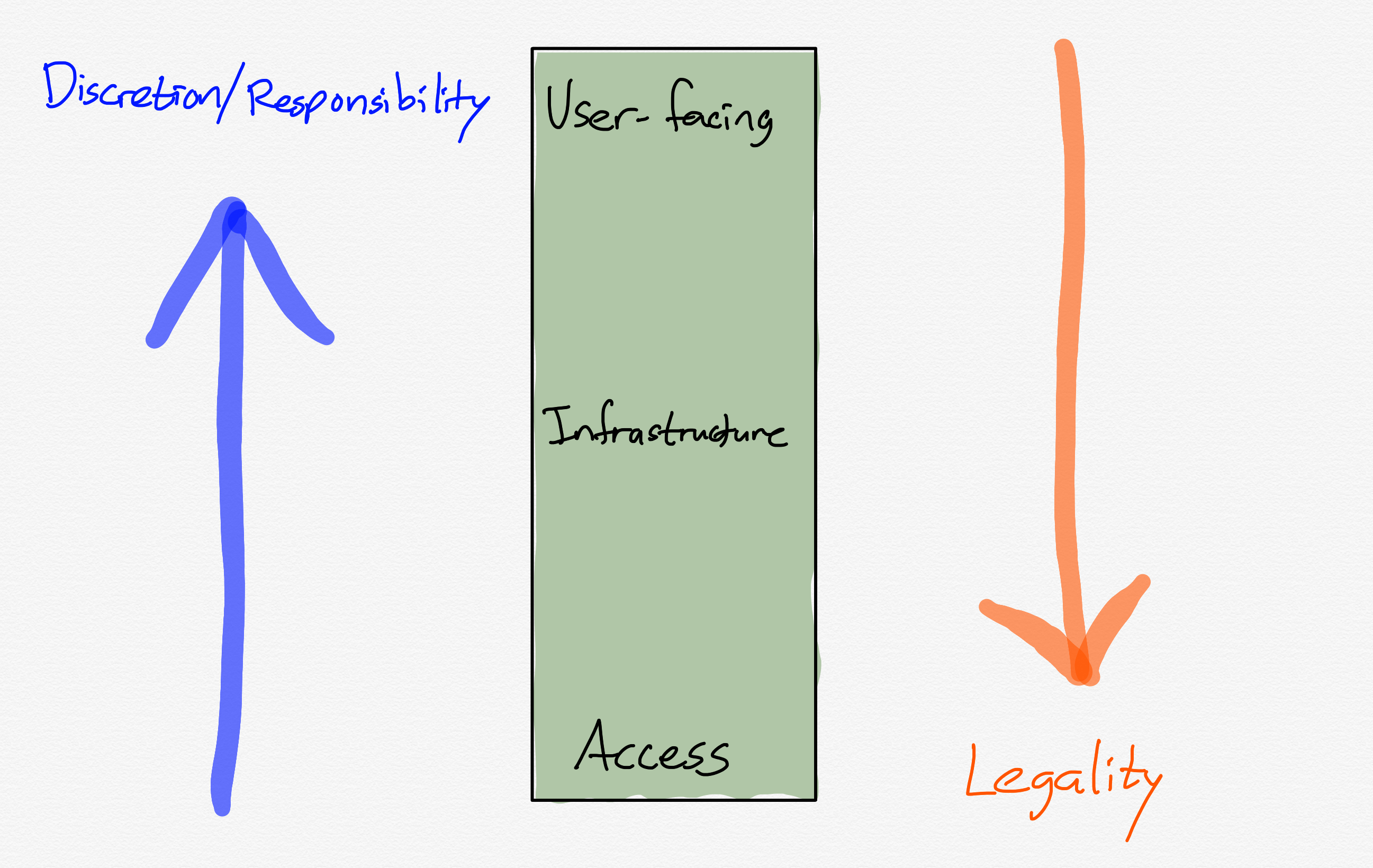

This applies to every part of my stack: because information is so easily spread across the Internet via infrastructure maintained by countless companies for their own positive economic outcome, I can write this Article from my home and you can read it in yours. That this isn’t even surprising is a testament to the degree to which we take the Internet for granted: any site in the world is accessible by anyone from anywhere, because the Internet makes moving data free and easy.

Indeed, that is why my critique of Manjoo’s article specifically and the ongoing privacy hysteria broadly is not simply about definitions or philosophy. It’s about fundamental assumptions. The default state of the Internet is the endless propagation and collection of data: you have to do work to not collect data on one hand, or leave a data trail on the other. This is the exact opposite of how things work in the physical world: there data collection is an explicit positive action, and anonymity the default.

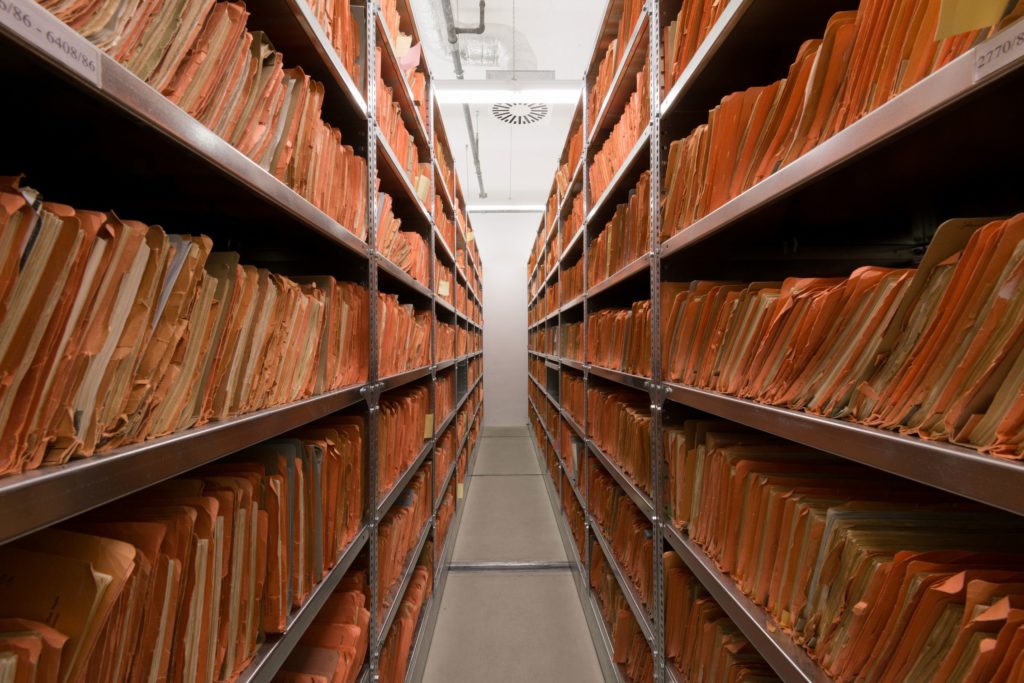

That is not to say that there shouldn’t be a debate about this data collection, and how it is used. Even that latter question, though, requires an appreciation of just how different the digital world is from the analog one. Consider one of the most fearsome surveillance entities of all time, the East German Stasi. From Wired:

The German Democratic Republic dissolved in 1990 with the fall of communism, but the documents assembled by the Ministry for State Security, or Stasi, remain. This massive archive includes 69 miles of shelved documents, 1.8 million images, and 30,300 video and audio recordings housed in 13 offices throughout Germany. Canadian photographer Adrian Fish got a rare peek at the archives and meeting rooms of the Berlin office for his series Deutsche Demokratische Republik: The Stasi Archives. “The archives look very banal, just like a bunch of boring file holders with a bunch of paper,” he says. “But what they contain are the everyday results of a people being spied upon.”

That the files are paper makes them terrifying, because anyone can read them individually; that they are paper, though, also limits their reach. Contrast this to Google or Facebook: that they are digital means they reach everywhere; that, though, means they are read in aggregate, and stored in a way that is only decipherable by machines.

To be sure, a Stasi compare and contrast is hardly doing Google or Facebook any favors in this debate: the popular imagination about the danger this data collection poses, though, too often seems derived from the former, instead of the fundamentally different assumptions of the latter. This, by extension, leads to privacy demands that exacerbate some of the Internet’s worst problems.

- Facebook’s crackdown on API access after Cambridge Analytica has severely hampered research into the effects of social media, the spread of disinformation, etc.

- Privacy legislation like GDPR has strengthened incumbents like Facebook and Google, and made it more difficult for challengers to succeed.

- Criminal networks from terrorism to child abuse can flourish on social networks, but while content can be stamped out private companies, particularly domestically, are often limited as to how proactively they can go to law enforcement; this is exacerbated once encryption enters the picture.

Again, this is not to say that privacy isn’t important: it is one of many things that are important. That, though, means that online privacy in particular should not be the end-all be-all but rather one part of a difficult set of trade-offs that need to be made when it comes to dealing with this new reality that is the Internet. Being an absolutist will lead to bad policy (although encryption may be the exception that proves the rule).

Apple’s Fundamentalism

This doesn’t just apply to governments: consider Apple, a company which is staking its reputation on privacy. Last week the WebKit team released a new Tracking Prevention Policy that is taking clear aim at 3rd-party trackers:

We have implemented or intend to implement technical protections in WebKit to prevent all tracking practices included in this policy. If we discover additional tracking techniques, we may expand this policy to include the new techniques and we may implement technical measures to prevent those techniques.

Of particular interest to Stratechery — and, per the opening of this article, Manjoo — is this definition and declaration:

Cross-site tracking is tracking across multiple first party websites; tracking between websites and apps; or the retention, use, or sharing of data from that activity with parties other than the first party on which it was collected.

[…]

WebKit will do its best to prevent all covert tracking, and all cross-site tracking (even when it’s not covert). These goals apply to all types of tracking listed above, as well as tracking techniques currently unknown to us.

In case you were wondering,4 yes, this will affect sites like Stratechery, and the WebKit team knows it (emphasis mine to highlight potential impacts on Stratechery):

There are practices on the web that we do not intend to disrupt, but which may be inadvertently affected because they rely on techniques that can also be used for tracking. We consider this to be unintended impact. These practices include:

- Funding websites using targeted or personalized advertising (see Private Click Measurement below).

- Measuring the effectiveness of advertising.

- Federated login using a third-party login provider.

- Single sign-on to multiple websites controlled by the same organization.

- Embedded media that uses the user’s identity to respect their preferences.

- “Like” buttons, federated comments, or other social widgets.

- Fraud prevention.

- Bot detection.

- Improving the security of client authentication.

- Analytics in the scope of a single website.

- Audience measurement.

When faced with a tradeoff, we will typically prioritize user benefits over preserving current website practices. We believe that that is the role of a web browser, also known as the user agent.

Don’t worry, Stratechery is not going out of business (although there may be a fair bit of impact on the user experience, particularly around subscribing or logging in). It is disappointing, though, that the maker of one of the most important and the most unavoidable browser technologies in the world (WebKit is the only option on iOS) has decided that an absolutist approach that will ultimately improve the competitive position of massive first party advertisers like Google and Facebook, even as it harms smaller sites that rely on 3rd-party providers for not just ads but all aspects of their business, is what is best for everyone.

What makes this particularly striking is that it was only a month ago that Apple was revealed to be hiring contractors to listen to random Siri recordings; unlike Amazon (but like Google), Apple didn’t disclose that fact to users. Furthermore, unlike both Amazon and Google, Apple didn’t give users any way to see what recordings Apple had or delete them after-the-fact. Many commentators have seized on the irony of Apple having the worst privacy practices for voice recordings given their rhetoric around being a privacy champion, but I think the more interesting insight is twofold.

First, this was, in my estimation, a far worse privacy violation than the sort of online tracking the WebKit team is determined to stamp out, for the simple reason that the Siri violation crossed the line between the physical and digital world. As I noted above the digital world is inherently transparent when it comes to data; the physical world, though — particularly somewhere like your home — is inherently private.

Second, I do understand why Apple has humans listening to Siri recordings: anyone that has used Siri can appreciate that the service needs to accelerate its feedback loop and improve more quickly. What happens, though, when improving the product means invading privacy? Do you look for good trade-offs, like explicit consent and user control, or do you fear a fundamentalist attitude that declares privacy more important than anything, and try to sneak a true privacy violation behind everyone’s back like some sort of rebellious youth fleeing religion? Being an absolutist also leads to bad behavior, because after all, everyone is already a criminal.

Towards Trade-offs

The point of this article is not to argue that companies like Google and Facebook are in the right, and Apple in the wrong — or, for that matter, to argue my self-interest. The truth, as is so often the case, is somewhere in the middle, in the gray.5 To that end, I believe the privacy debate needs to be reset around these three assumptions:

- Accept that privacy online entails trade-offs; the corollary is that an absolutist approach to privacy is a surefire way to get policy wrong.

- Keep in mind that the widespread creation and spread of data is inherent to computers and the Internet, and that these qualities have positive as well as negative implications; be wary of what good ideas and positive outcomes are extinguished in the pursuit to stomp out the negative ones.

- Focus policy on the physical and digital divide. Our behavior online is one thing: we both benefit from the spread of data and should in turn be more wary of those implications. Making what is offline online is quite another.

This is where the Stasi example truly resonates: imagine all of those files, filled with all manner of physical movements and meetings and utterings, digitized and thus searchable, shareable, inescapable. That goes beyond a new medium lacking privacy from the get-go: it is taking privacy away from a world that previously had it. And yet the proliferation of cameras, speakers, location data, etc. goes on with a fraction of the criticism levied at big tech companies. Like too many fundamentalists, we are in danger of missing the point.

I wrote a follow-up to this article in this Daily Update.

- This matches the 31 dots in Manjoo’s graphic; I did not count HTML documents or CSS files [↩]

- I do address these services and others in the Stratechery Privacy Policy [↩]

- Let’s be charitable and ignore the fact that the most egregious trackers from Manjoo’s article — by far — are news sites, including nytimes.com [↩]

- Or if you think I’m biased, although, for the record, I conceptualized this article before this policy was announced [↩]

- And frankly, probably closer to Apple than the others, the last section notwithstanding [↩]