It’s late in the afternoon after a full day of actions in a week long campaign. People are starting to feel weary and sluggish under the baking hot sun and the exhaustion of thinking is only made worse by the sniping and grizzling everyone seems to be using against each other. The day’s almost at an end and all you want to do is sit down in the shade, take off your shoes and drink some water. Everyone else in the affinity group seems keen to get out of there as soon as possible and go to the pub, but you also want to raise with the group a concern about the action and you’re not sure that people want to listen.

*

It’s 1 o’clock in the morning at an overnight encampment, cool air feeling like it’s freezing your damp clothing. The night has been fairly uneventful, save for a small but loud argument a few hours ago, and your body is nagging you to sleep. The next buddy team is due to come on shift and mind the first aid tent until the morning soon and you’re waiting for them to arrive.

*

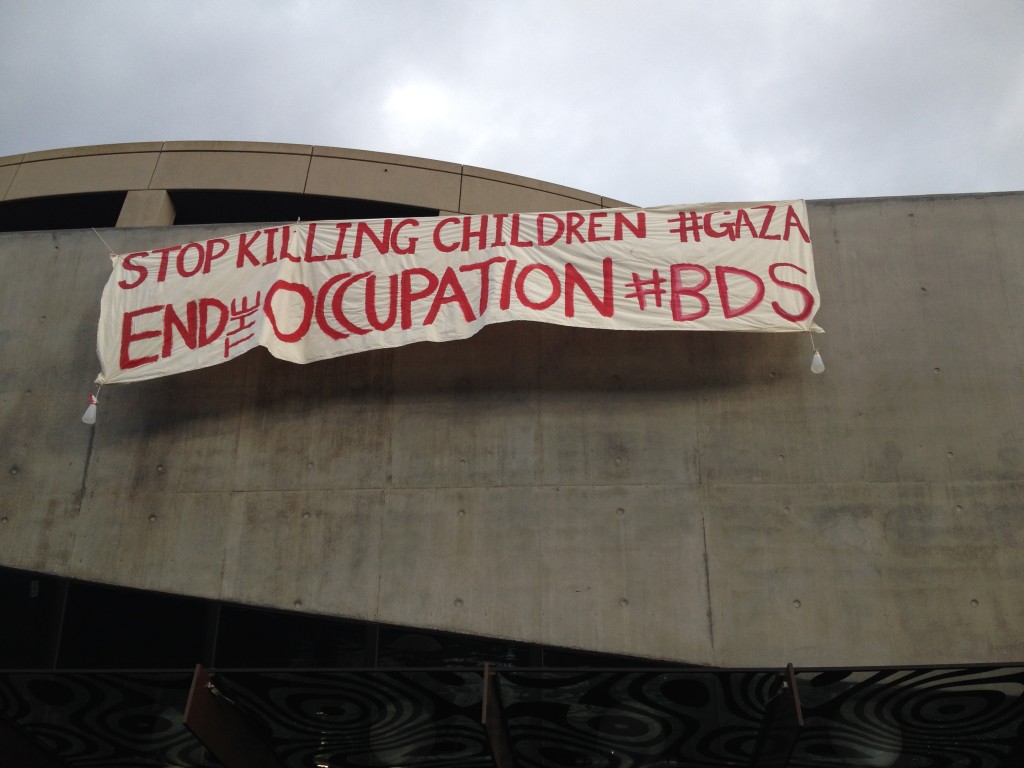

Today you have been taking part in a solidarity vigil against the forced deportation of a refugee from a detention centre. The vigil has progressed very smoothly, with no incidents and a good atmosphere amongst those who have attended. Yet, in listening to the speeches you couldn’t help but feel upset and a little disturbed by what you heard and it has started to make you feel quite stressed and anxious. On the outside, you seem okay – you don’t want to feel like you’re letting other people down. After all, you’ve been at these sorts of actions many times before without a problem, why start to worry now?

*

Each of the situations described above are not unusual situations to find yourself in when participating in protests. Long days and nights with little rest and even less sleep can grind even the most hardy down, while personal and political concerns can suddenly flare and become vitriolic. In order to deal with these issues and, if possible, prevent them from getting out of control we encourage affinity groups and even individuals to debrief after actions.

Debriefing is a process by which people come together after an incident or event to discuss what has happened and to come to a common understanding of what has just occurred. It is a useful opportunity to check in with other people and make others aware of how you are feeling, and to flag concerns or issues that arose during the incident; perhaps its primary use is being the first step in recognising and acting against Critical Incident Stress if there has been a traumatic incident. Through debriefing, questions such as “Did I/we do the right thing?”, “Is it okay to feel like this?”, “Should I/we have done more?” can be directly addressed and resolved, rather than leaving them to fester in the back of our minds.

It is important to keep in mind that trauma is subjective: different people may be affected by one situation in radically different ways depending on earlier traumas, coping techniques and a whole range of other factors. Hence the third example, above: in this case it is not seeing an act of violence, suffering or seeing a physical injury that has caused the trauma. Instead, repeated exposure to stories of severe suffering has taken its toll and the person in the example is experiencing emotional distress. You may also note that the example does not specify that the person is acting as a Street Medic: this process obviously has its benefits for medics (as the nature of our work at protests places us at a higher risk of encountering traumatic situations), but it is something that all protesters and affinity groups should consider and embrace. Trauma is by no means monopolised by Street Medics.

So, the advantages of debriefing amongst affinity groups are two-fold: to maintain and strengthen the affinity of the group, and to look out for the mental welfare of affinity group members.

How to debrief

Melbourne Street Medic Collective’s practice when it comes to debriefing is to debrief after every action, with an open invitation for non-medics to also attend. Sometimes this means debriefs are very short and quickly over and done with. Other times it has proved the opportunity for concerns to be aired, openly and without prejudice, and either quickly resolved or deferred upon agreement to a more convenient and appropriate time and setting.

We have also found it most effective to conduct debriefings as soon after the event/incident as possible and will generally move to a quiet area to debrief once the action has begun to wind up, so long as there are no immediate concerns/incidents to be dealt with.

Once assembled, someone volunteers to facilitate/chair the debrief and we conduct a check-in: taking it in turns to greet the group, describe how we’re feeling (“I’m all good”, “I feel like shit”, “I’m okay but I was pretty stressed for a while when the cops were getting aggro”, etc.) and briefly – i.e., one or two sentences – describe how we feel the action went.

For Street Medic collectives it is often useful to follow check-ins with any report-backs about incidents during the action (mostly because these may have been referenced during the check-in). Otherwise, a call is made for anyone to raise any concerns or points of praise for the action. This can be conducted in a similar manner to the check-in, with input from each person in the group, or input can be received through a general call-out to the group.

If a point is raised, it is important to remember that this process is intended to be constructive and that we need to be respectful of one another, even if the issue is of a personal nature.

Concerns should be raised without attacking a person, and responses called for after the first person has been given time to raise and explain their concern. Responses should be directed at the issue, not the person, and the discussion managed in such a way as to prevent digression or rambling. Here, active listening and non-violent communication skills are invaluable.

If needed, a two-minute time limit on speaking can be used and a speaker’s list employed to ensure the conversation is open to all and not dominated by a few key voices. Here, the role of the facilitator is key and to that end we have included some information about facilitation skills below.

Discussion should be directed towards finding a resolution but, if this is not possible (after all, Rome wasn’t built in a day) within the current debriefing space, the group should aim towards setting another date and time in the near-future to further discuss and hopefully resolve the issue. If for some reason this cannot be arranged, emphasis should be put on trying to organise this as soon as possible in the following days.

To recap:

1. After the action, find a quiet place away from the action.

2. Nominate a facilitator.

3. Conduct check-ins (How are you feeling/How do you think the action went?).

4. Make any report-backs.

5. Ask group members if they have any issues they want to raise or any general comments on the action.

6. If needed, agree on a date and time to follow up from the debrief.

http://melbsmc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/facilitating_group_agreements.pdf

http://melbsmc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/facilitating_difficult_behaviour.pdf