Brodie Waddell

Hundreds of people complete a doctorate in History each year at UK universities, a process with huge implications for the strength and sustainably of academic history as a discipline. This figure has been rising gradually but fairly consistently over the past couple decades, from around 250 in the late 1990s, to around 550 in the late 2000s, to a peak of more than 750 in 2016.

In previous posts, I’ve discussed the job market for History PhDs using various measures including staff/PhD ratios, cohort studies and job listing data. None of the numbers present an especially rosy picture for newly completed PhDs searching for an academic post.

However, in response to each of these posts, readers have rightly asked about the motives of those pursuing doctorates. It is obvious that not all of those 700 or more new PhDs want to become lecturers, so the job market is thus presumably less disastrous than the headline figures imply. But the problem is that it is difficult to know whether this proportion is substantial or negligible.

Thankfully, Andy Burn not only brought it to my attention that there is a UK-wide survey of current PhD students about this, but also very generously turned the raw data into something useable for me. This is the ‘Postgraduate Research Experience Survey’ (PRES) and it asks all sorts of questions, including two about motivations. The highest recent response rate was in the 2017 survey and that’s what I’ve used here, though the proportions were similar in the 2018 survey.

So, what are the results for History?

Almost half of doctoral students in History, when asked directly why they chose to do a PhD, said that they were motivated by their interest in the subject (48%). This is a much higher proportion than in most other disciplines such as clinical medicine (30%), biology, chemistry or computer science (35%), though it is similar to literature (43%), classics (48%) and, intriguingly, mathematics (48%). It is only lower than philosophy (57%).

Less than a quarter said that their ‘main motivation’ was an academic career (22%), lower than the average across all disciplines (27%), though in the same general range of most humanities subjects (20-30%). Perhaps surprisingly, subjects like medicine and health, comp sci, architecture and even ‘business and management studies’ had higher proportions than history.

An optimistic reading of the answers to this question would be that most people who take History PhDs are doing it for the love of history and only a minority want an academic job. If so, this is good news both for those pursuing academic jobs – because there would be less applicants per post – and for the remainder – because they will not be disappointed about the lack of academic jobs available.

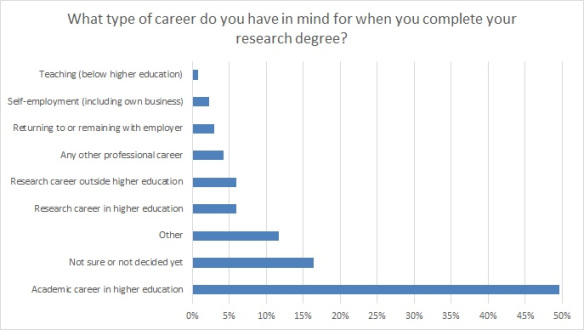

However, the next question on the survey suggests this optimistic reading may be too rosy. When History PhDs are asked what type of career they ‘have in mind’ for their future, the proportion thinking of a lectureship is much higher, reaching almost precisely 50 percent, and another six percent want a ‘research career in higher education’. A further 28% are ‘unsure’ or ‘other’. Indeed, the number definitely not envisioning an academic career is only 16%. So, although we can be sure that more than 100 of the 700 or so new History PhDs each year are not planning to enter the academic job market, it seems like a significant majority – perhaps 400 to 500 – will be applying for university posts.

When compared to other disciplines, the 56% of History PhDs who are definitely aspiring academics is a high proportion. The average across all subjects is 50%, with 39% aiming for an ‘academic career’, plus another 11% for a ‘research career in higher education’. It is higher in literature (69%), philosophy (69%), law (63%) and economics (58%), but unsurprisingly lower in medicine (40%) and other STEM subjects. Presumably ‘alt-ac’ pathways are rather easier to envision among the latter group.

I’ll leave it to others to decide whether they think this data offers ‘optimistic’ or ‘pessimistic’ news for recent and current PhDs. What is absolutely clear is that doctoral students in history care passionately about their subject, whether or not they hope that it will lead to an academic career.

I’m reading the chapter in my 1982 edition of Alice Clark (the only history book I stole from my mother’s bookshelves), complete with a woodcut of a woman haymaking on the cover (although this image has been edited to remove the couple canoodling in the background which is present in the original below). Is this deeply significant? Probably not …

I’m reading the chapter in my 1982 edition of Alice Clark (the only history book I stole from my mother’s bookshelves), complete with a woodcut of a woman haymaking on the cover (although this image has been edited to remove the couple canoodling in the background which is present in the original below). Is this deeply significant? Probably not …

Those who have never read Alice Clark’s Working Life of Women might wonder why we would pay any attention to a work that is a hundred years old, and superseded by recent research on women. Yet anyone who works on the history of women, and particularly the history of women’s work, in early modern England owes a debt to Alice Clark’s work. It was reissued in 1982 with an introduction by Miranda Chaytor and Jane Lewis, and again in 1992 with an introduction by Amy Erickson. As Natalie Davis noted in a paper delivered at the Second Berkshire Conference in 1974, Clark consulted archives, differentiated among women, and had an overarching theory.

Those who have never read Alice Clark’s Working Life of Women might wonder why we would pay any attention to a work that is a hundred years old, and superseded by recent research on women. Yet anyone who works on the history of women, and particularly the history of women’s work, in early modern England owes a debt to Alice Clark’s work. It was reissued in 1982 with an introduction by Miranda Chaytor and Jane Lewis, and again in 1992 with an introduction by Amy Erickson. As Natalie Davis noted in a paper delivered at the Second Berkshire Conference in 1974, Clark consulted archives, differentiated among women, and had an overarching theory. At first glance Alice Clark seems the most unlikely of historians. Due to ill health she managed only sporadic periods at school and she never went to university. She was a capitalist, not a scholar, spending most of her adult life as a director of the family business, known today as Clarks Shoes Ltd. Yet from a young age she was a voracious reader and would have joined her sister at Cambridge had her parents not felt strongly that the shoe company would benefit from the involvement of a female family member.

At first glance Alice Clark seems the most unlikely of historians. Due to ill health she managed only sporadic periods at school and she never went to university. She was a capitalist, not a scholar, spending most of her adult life as a director of the family business, known today as Clarks Shoes Ltd. Yet from a young age she was a voracious reader and would have joined her sister at Cambridge had her parents not felt strongly that the shoe company would benefit from the involvement of a female family member.