This is a transcript of a talk I gave at Bend the Arc’s 2020 Conference, Pursuing Justice, on rising white nationalism and antisemitism in the era of COVID-19.

—–

I’m going to tell you a story about white nationalism in the era of COVID-19.

On Saturday, April 18, one of the first protests against coronavirus public health measures was held in front of the state house in Columbus, Ohio.

The protests attracted many demonstrators, including white nationalists.

One white nationalist held an openly antisemitic sign with an offensive caricature, saying that Jews are “the real plague”.

A journalist later identified the white nationalist as 36-year old Matt Slatzer of Canton, Ohio, from the organization National Socialist Movement. The N.S.M leads the Nationalist Front, an umbrella organization that consists of neo-Nazis, traditional white supremacists, and racist skinheads.

Slatzer told journalist Nate Thayer that “The Jews are responsible for the Corona virus” and continued with a series of conspiracy theories blaming Jews for forcing political leaders, from behind the scenes, to enforce the shut down and quarantine. He claimed all COVID vaccines are a Jewish conspiracy to poison people.

He complained that even as he and many Ohioans were unable to work, the federal government was spending $2 trillion to bail out the rich and powerful. In Slatzer’s antisemitic interpretation: “Why are these Jewish controlled corporations getting all the money and those of us who work for a living getting nothing? How much are the CEO’s of the big companies being paid? We are both not allowed to go to work and getting no support from the government.”

How much sympathy was he able to generate from others at the rally by framing his antisemitism in language that taps into the widespread misery of working people and anger at corporate greed in this moment? Why did nobody at the rally stop him? And how many other white nationalists like him were out there spreading antisemitism, racism, and twenty-first century civil war narratives?

As the coronavirus crisis unfolds, white nationalists are increasing their recruitment and radicalization efforts, hoping to tap into suffering, resentment and uncertainty to build their movements.

Online, far-right social media leans into anti-Semitic conspiracy theories. In their groups and forums, Jews “invented” the coronavirus to secure world domination and financial profit. They claim that the virus is a bioweapon funded by Jewish philanthropist George Soros, who has become the target of choice for right-wing conspiracy theories in the U.S. and Europe.

Nor is far-right bigotry limited to sign-making and spreading offensive memes. Earlier in April, a white nationalist was arrested on suspicions of planning an attack on a Missouri hospital. He also had plans to attack a mosque and a synagogue. His justification: the federal government was using the pandemic as an “excuse to destroy our people”, meaning the white race. For him, the pandemic is a “Jewish power grab”. Words and ideas have consequences. We can only be thankful that the call by white nationalist groups to intentionally try to spread the coronavirus to Jews has, so far it seems, gone unanswered.

Nor is antisemitism in the time of the pandemic limited to internet provocateurs and would-be mass murderers. Mainstream right-wing leaders are drawing on the familiar language of conspiracy and scapegoating, to deflect blame from their anti-science, anti-human policies and pet causes.

Trump’s newly appointed spokesman for the Department of Health and Human Services, among others, has claimed George Soros is behind the COVID pandemic in some form. Trump himself, along with right-wing politicians like Florida Representative Matt Gaetz, and popular Fox News anchors like Tucker Carlson have blamed ‘globalists’, another antisemitic dog whistle, for the unfolding crisis. Pastor Rick Wiles, whose TruNews network still holds White House press credentials, said God is spreading COVID in synagogues to punish “those who oppose his son, Jesus Christ”.

This rise in white nationalism and antisemitism is occurring alongside a rise in anti-Asian racism and anti-immigrant xenophobia, which we’ll discuss.

White nationalists have been waiting for a crisis like this to organize, and right-wing politicians are adept at using a crisis like this to advance rhetoric and policies of bigotry and exclusion. But we can use this crisis as well, to advance our own transformative vision of a better world.

So today, WNs are organizing in the streets and online, and committing mass shootings-

We remember the 11 Jews martyred at Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, the one Jewish victim at a synagogue in Poway California, the 23 members of the Latinx community murdered in El Paso Texas, the 51 Muslims murdered in Christchurch, the 9 black worshippers killed in a Charleston SC church in 2015, the at least 28 people murdered by misogynst anti-feminist and incel shooters since 2014, and more.

Now, white nationalists are not just a marginal, exotic movement. They’re a well-organized political force that played a critical role in the election of President Trump in 2016.

From 2017 to 2019, SPLC reported a 50% increase in white nationalist groups.

The movement is growing, even as many movement leaders have been driven underground due to deplatforming, doxxing, lawsuits, infighting and more.

White nationalism enjoys an expanding potential base of support across the U.S. landscape. Studies indicate that millions of White Americans hold a strong attachment to a sense of White identity and grievance politics, and millions also fear that the effects of the country becoming majority non-White by 2045 will be mostly negative.

White nationalism is on the rise.

And when we say white nationalism, we’re not just talking about online trolls, white power groups and mass shooters, terrible as those things are. Today, in the Trump era, we’re seeing white nationalism spread from the periphery to the center of mainstream right-wing politics in America. White nationalists are part of the Republican coalition, alongside the Christian Right. This gives them a pipeline into national politics and leadership positions.

- We’ve seen many white nationalists run for elected office and attempt to embed themselves in local Republican party infrastructures, and campus conservative groups, across the country.

- Often they rebrand themselves as good old patriotic, Christian “American Nationalists”, selectively downplaying their extreme views on antisemitism and white pride, as part of a strategy to influence movement conservatism from within.

- White nationalists have been exposed as employees of prominent conservative think tanks and policy outfits, journals, newspapers and other institutions.

- For them, this is part of a long-term strategy of social transformation, trying to shift the boundaries of acceptable discourse further to the Right, and gradually transform the basic common-sense worldview held by millions of Americans.

At the same time, prominent conservative leaders are meeting them halfway- dancing further to the Right, and increasingly sounding like white nationalists.

The core belief of white nationalism is that the ‘white race’ in America and Europe is undergoing a gradual extinction, through massive non-white immigration. White nationalists call this the great replacement or white genocide. They’re opposed to any and all immigration of non-whites, as a demographic threat which spells in their eyes the physical, biological survival of the white race, is core to their worldview.

Prominent right-wing pundits like Fox News’ Tucker Carlson and Laura Ingraham, who command nightly audiences of millions of people, increasingly adopt “great replacement” rhetoric to claim that ‘real Americans’ are being ‘replaced’ by an “invasion…of illegal immigrants”. This brings white nationalist ideas about immigration and demographics smack dab into the middle of public discourse.

Mainstream right-wing pundits on Fox and elsewhere also provide cover for white nationalists, downplaying the threat they pose or even their existence while retweeting them, protesting their ‘censorship’ when social media platforms remove their accounts, and even sometimes inviting them on their shows.

White nationalism is shaping anti-immigrant policy, as well.

Throughout the four years of the Trump administration, White House staffers with affinities for white nationalism, from Steve Bannon to Stephen Miller- who, by the way, is a shonda- have pushed draconian anti-immigrant policies- from concentration camps at the border to family separations, rewriting asylum law, continued attempts at a Muslim ban, and moving to suspend immigration entirely in the era of COVID-19.

In public and in private, they mount their anti-immigrant crusade using the white nationalist language of demographic change.

These policies are being pushed by radical anti-immigrant organizations closely aligned with white nationalists, like the Federation for American Immigration Reform and Center for Immigration Studies, who echo white nationalist talking points of demographic change. For years these think tanks were considered fringe, but they now enjoy a direct pipeline to the White House and mainstream politicians and media outlets.

White nationalist antisemitism is moving mainstream, as well. Trump and other right-wing politicians like Matt Gaetz, Josh Hawley, Kevin McCarthy, Louie Gohmert and more, as well as media outlets like Fox News, use dog-whistle antisemitic conspiracy theories, scapegoating liberal Jewish philanthropist George Soros or “globalist elites” as the hidden puppeteers of left-wing causes.

In the past few years, they’ve claimed Soros is the hidden puppeteer of so many liberal causes- like non-white immigration into the U.S.; protests against the nomination of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh; black lives matter; antifa; the impeachment proceedings against Trump; and more.

This all creates a call-and-response type of feedback loop, between mainstream right-wing leaders and white nationalists.

Right-wing leaders like Trump and Fox News use white nationalist conspiracies about Jews, immigration and demographics as a powerful tool, helping them consolidate support for their racist and nationalist policy agenda.

White nationalists are thrilled, because their ideas are granted legitimacy and a massive public forum, giving them more opportunities to win new recruits and pull mainstream discourse even further to the Right.

They become inspired to commit more attacks against Jews, immigrants and other minorities, as Dove explained earlier in the Pittsburgh example.

So what about today, in the era of COVID-19?

To quote veteran antifascist researcher and organizer Scot Nakagawa- “For white nationalists, this pandemic may be right on time. Because when it comes to sheltering in place, white nationalists are the experts.”

In this moment, our political and economic systems are being exposed as fragile and unsustainable, and the future feels radically uncertain. White nationalists are intent on capitalizing on this uncertainty, hoping to tap into widespread suffering and resentment to build their movement.

Many white nationalists dream of using this crisis to further their accelerationist vision of collapsing government, inciting a civil war, and fomenting revolution (not the good kind).

Others hope to further their goal of transforming mainstream conservatism, pulling it even further in the direction of exclusion, expulsion and a drastically constricted sense of who is rightfully part of the nation–who is the “We.”

As I discussed earlier, white nationalists are increasing their recruitment and radicalization efforts in online spaces, and spreading antisemitic conspiracy theories. They’re helping organize anti-lockdown protests across the country, and showing up, alongside adjacent movements like the Patriot and militia movements.

Much like Trump rallies, they see these anti-lockdown protests as prime spaces to win new recruits and spread their messaging.

Right-wing leaders like President Trump, meanwhile, are staring down a mounting groundswell of popular unrest, as we’re entering the worst economic collapse since the Great Depression. They know that millions of people facing widespread immiseration will be looking for someone to blame, and they’re eager to provide scapegoats, in order to distract blame from themselves.

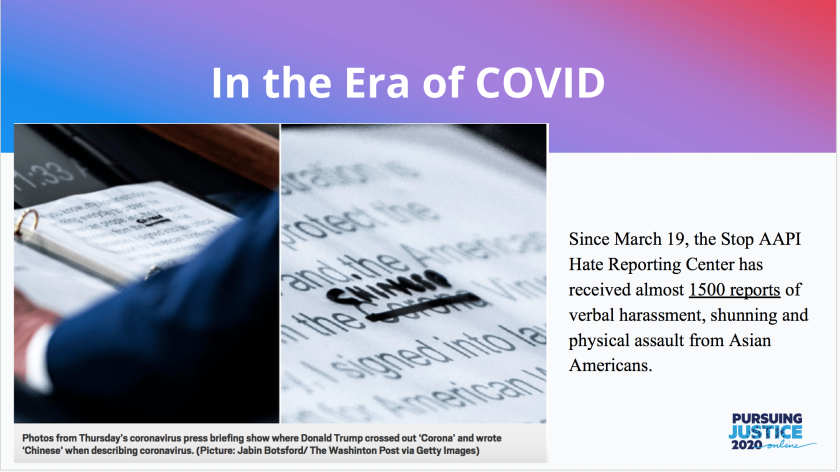

They’re doubling down on anti-China scapegoating, spreading racist rhetoric, like ‘Chinese coronavirus’ or ‘Wuhan flu’, to scapegoat China as a ‘backwards’ primitive country, and a menacing, powerful rival, uniquely responsible for the spread of coronavirus around the world.

Across the country, mounting anti-China rhetoric has driven a spike in harassment and physical attack against Asian American-Pacific Islander communities. Since its launch on March 19, the Stop AAPI Hate Reporting Center has received almost 1500 reports of verbal harassment, shunning and physical assault from Asian Americans.

Right wing leaders also are using the crisis to bolster the scapegoating of immigrants, the closing of borders and a broader America First nationalist agenda. Channeling fascist impulses, Trump places himself above science and expertise, deploying motifs of the cult of a leader and the myth of national greatness- a greatness that has supposedly been ‘compromised’ by internationalism and liberalism.

As things get worse, the Right will also need an image of the ‘elites’ to blame. They will need to point the finger at a caricature of a powerful, subversive internal enemy who is responsible, from behind the scenes, for what went wrong. Otherwise, who else are people going to blame for what went wrong at the top- Trump?!?

This is where antisemitism comes in. We’re already seeing Tucker Carlson, Trump and other right-wing leaders scapegoat ‘globalists’ for the mounting public health crisis, and economic fallout, brought on by COVID.

We know this is how antisemitism functions- getting people to blame a familiar stereotype of a shadowy, powerful elite conspiracy operating behind the scenes, in order to deflect blame from the failed systems, policies and leaders responsible for widespread suffering.

As many others have said, we can’t hope to block the rising climate of bigotry and intolerance by wishing for a return to ‘normal’. We’re living through a moment of profound transformation. The center cannot hold, and a political realignment is inevitable.

An influential right-wing economist named Milton Friedman once said that “only a crisis produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around.”

It’s up to us to use this coronavirus crisis to advance our powerful, transformative vision of a better and more just world, a multiracial democracy where everyone can thrive. For the radical right, too, has their own ideas lying around.