Arthur Ransome dismounting a train in Soviet Russia

Or, a review of The Last Englishman; The Double Life of Arthur Ransome by Roland Chambers

Arthur Ransome dismounting a train in Soviet Russia

Or, a review of The Last Englishman; The Double Life of Arthur Ransome by Roland Chambers

In an interview published in the latest

Socialist Review, the great journalist John Pilger was asked, 'Every year now sees a generation of journalism graduates failing to find work in the media. What would you say to young people who want to enter journalism to hold power to account?' and replied that:

I would say that the BBC and the Murdoch press are not for you. Become a freelance; maintain your independence and, above all, your principles. Remember that journalism is a privilege and that you are an agent of ordinary people, not of those who seek to control them. Journalism is about humanity, and your responsibility is to report the world from the ground up, not the other way round.

One freelance journalist who has done this through reporting the student revolt in Britain is Pilger's fellow

New Statesman columnist Laurie Penny. When the revolt subsided over the Christmas break, Penny, having safely won much praise and number of plaudits (including 'Histomat Socialist Blogger of the Year 2010', let's not forget), decided to do what many liberal-lefty columnists tend to do when they run short of material - have a dig at the Socialist Workers Party, mainly for, er, still selling

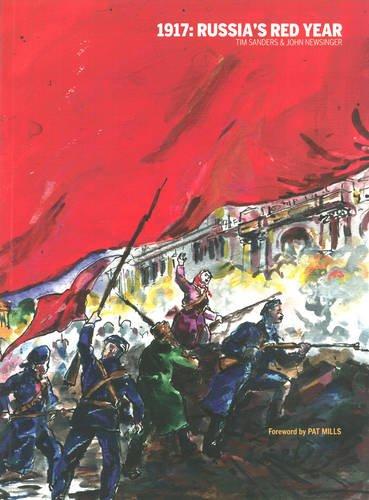

Socialist Worker in the age of the internet and generally acting like some 'cultish Petrograd-enactment society' i.e. arguing the Bolshevik Revolution remains an inspiration for anti-capitalists in the 21st century. Those who want to get into the Laurie Penny-SWP debate can get into it via

Lenin's Tomb, but what I want to do is explore the question of journalists and revolutionary struggle - in particular Arthur Ransome and, (sorry Laurie yes), the er, Russian Revolution. This will be done by way of a short book review of Roland Chambers recent biography - also reviewed

here and

here - and hopefully may go someway to clarifying why revolutionary Petrograd remains an inspiration today.

There is an old saying, don’t judge a book by its cover – and this adage needs to be remembered with Roland Chambers' new biography of Ransome -

The Last Englishman: The Double Life of Arthur Ransome - as much as ever. If the title is incredibly confusing – and not explained in the text itself bar a passing reference to the fact that at one point it seemed – to Ransome himself at least – that he ‘was the last Englishman in Moscow’ during the Russian Revolution, then the subtitle hardly helps – ‘the double life of Arthur Ransome’. Roland Chambers tells us he was initially aiming in the aftermath of released classified documents in 2005 proving that he he had been recruited by the British government as an agent of the newly formed MI6 to write ‘a brief and colourful exposé, a sharp adjustment to the whitewash that hitherto has screened Ransome from anything approaching a candid assessment.’ The fact that the former head of MI5 Stella Rimington is quoted on the front describing the work as ‘fascinating’ might be enough to put any self-respecting socialist off.

However, fortunately, Chambers’ work offers more than this. As he writes, ‘very quickly I realised that his life, as well as the age that he lived through, offered something much richer.’ This should not have been much of a discovery – Ransome’s rich and varied life has long since attracted historians and biographers, above all Hugh Brogan. But let Chambers continue:

‘

No other Englishman saw the war and Revolution from so many points of view. No other journalist so effectively blended the rhetoric of conventional democracy with the radical doctrines of Marxism-Leninism. As a struggling writer in pre-war London, Ransome had befriended strident nationalists and equally strident internationalists. In the same way, between 1914 and Lenin’s death in 1924, he found himself on easy terms with arch-reactionaries and committed revolutionaries. Ransome was a bohemian and a conservative, a champion of self-determination and a an imperialist, a man who cherished liberty but assumed, as a matter of course, that liberty depended on a successful negotiation with power. The fascination of his story consists in the ease with which he adopted all the competing ideals of his generation. Yet Ransome, who longed, above all, to be included, did not consider himself a controversial figure. On the contrary, while others had lost themselves in uncertainty, forgotten who they were or how to live, he had always, he insisted, been the simplest of men’.

Smearing Ransome as 'an imperialist' seems to me to be quite unjustified, and indeed, contra Chambers, rather than leading a ‘double life’ – it seems to me that Ransome remained one man, albeit a many sided man, with fairly consistent principles and a basic if slightly naïve decency and honesty throughout. Moreoever, what emerges as most fascinating about Ransome’s story is not so much this sense of contradiction and ‘double consciousness’ that saw him essentially prove useful for different purposes to the Bolsheviks and the British government, even if never fully really trusted with anything important by either of them. Rather, what is really fascinating about Ransome’s life is the quite unlikely fact that this upper-middle class English journalist and writer of vaguely leftish liberal leanings happened more by accident than design to have been one of the outstanding witnesses of the Russian Revolution.

Chambers' grasp of the Russian Revolution is decidedly shaped by the dominant liberal discourse which portrays the urban insurrection in October 1917 as not the climax of the whole Revolution but rather as a Bolshevik coup. Yet he has done a lot of reading about the revolution and brings it to life generally successfully despite his own political prejudice and weak grasp of what he calls ‘Marxism-Leninism’. For example he sees Lenin’s small polemical pamphlet

What is to be done? as a ‘definitive manifesto’ which envisaged a ‘one party state’, rather than what it was, an intervention which in fact rather more modestly aimed to bring home to Russian Marxists the need for a revolutionary organisation with its own revolutionary paper in preparation for the coming revolutionary upheaval predicted by all careful observers of Russia’s development. As Ransome himself was to write of Lenin in 1919, in person he was far from the humourless, sour-faced, power-hungry plotter and schemer of legend:

‘More than ever, today, Lenin struck me as a happy man, and walking down from the Kremlin, I tried to think of any other great leader who had a similar, joyous, happy temperament. I could think of none. Napoleon, Caesar, did not make a deeper mark on the history of the world than this man in making, none records their cheerfulness. This little bald, wrinkled man who tilts his chair this way and that, laughing over one thing and another…Not only is he without personal ambition, but as a Marxist, believes in the movement of the masses…his faith in himself is the belief that he justly estimates the direction of elemental forces’

It is a pity that, while Chambers’ work focuses quite rightly on Ransome’s experiences as a journalist reporting the Russian Revolution, he either chose to ignore or did not seem to have come across Paul Foot’s 1992 excellent essay,

‘Arthur Ransome in Revolutionary Russia’ - (there is a short version online) written to introduce the republication after about 70 years of Ransome’s pamphlets written in the aftermath of the revolution. In any case, Chambers’ work missed the opportunity to bring out fully the real significance of Ransome’s life – though this theme shines throughout the work nonetheless.

Before Russia, as Foot noted, ‘what he lacked was any sort of clear commitment’ to or enthusiasm for politics. ‘He had not joined the newly-formed Labour Party or shown the slightest interest in any of the great issues which racked pre-war Britain; women’s suffrage, Irish independence or the great strikes of 1911 and 1912 which effectively destroyed the Liberal Party and shook the Tories to their foundations…Perhaps he yearned for the sort of world which William Morris painted in News from Nowhere, but felt that the reality of Britain in the first 14 years of the century was so far distant from anything Morris had hoped for that there was no point in taking up a political position’. Chambers tells us that Ransome attended meetings of the Fabian Society, 'debates which stirred him so deeply that he took long night walks into the country to clear his head...but his interest in politics rarely extended beyond a fashionable contempt for the "bourgeoisie".'

Rather like George Orwell going to fight in the Spanish Civil War, what changed everything for Ransome was the experience of witnessing a society in the midst of a great social revolution. Of course, the revolution had its dangers for a foreign journalist like Ransome still trying to get to grips with the Russian language. At one point in the midst of the February Revolution in Petrograd, a horseman galloped up to him, pointed a pistol in his face and demanded ‘For or against the people?’

‘I am English’, replied Ransome, helplessly.

‘Long live the English!’ shouted the horseman, and galloped away.

Yet as Foot noted, what Ransome saw in revolutionary Petrograd 'excited him so much that he became for the first and last time politically committed’. As Ransome later wrote in

The truth about Russia in 1918, ‘I do not think I shall ever be so happy in my life as I was during those first days when I saw working men and peasant soldiers sending representatives of their class and not of mine’ to the Petrograd Soviet – the workers council springing out of that revolt.

As Foot notes, ‘The key to his excitement was the new democracy. Representatives of a new class, previously dispossessed of property and power, were suddenly entering the political arena. News from Nowhere was News from Everywhere’. The soviets were the real democratic force – with electable and recallable delegates - democracy from below – and the Soviets were, as Foot notes, ‘a hundred thousand times more democratic than the parliaments of the West, which had never really interested him’. As Ransome wrote back home of the Petrograd Soviet, ‘It was the first proletariat parliament in the world, and by Jove it was tremendous’.

Though he now prepared notes in order to write a full history of the Russian Revolution to date, Ransome unfortunately missed his chance to watch the triumph of Soviet power in October, but rushed back in the aftermath. He arrived in time to witness the period when the Constituent Assembly – the old ‘democracy’ from above - was dissolved in 1918. As Foot notes, Ransome, ‘watching Trotsky in action explaining the government’s policies to hundreds of freezing soviet delegates in crude clothes, this moderate and restrained reporter, trained in the reserved language of British upper class education, wrote this:

‘ I felt I would willingly give the rest of my life if it could be divided into minutes and given to men in England and France so that those of little faith who say that the Russian Revolution is discredited could share for one minute each that wonderful experience’.

Such statements are even more remarkable as Ransome did not see the revolution as someone who was already a committed revolutionary socialist like say, John Reed, who wrote

Ten Days That Shook the World or Victor Serge (see his

Year One of the Russian Revolution) or Alfred Rosmer (

Lenin’s Moscow). Later, returning from the perils of the Russian civil war to his home city of Leeds to write what would become

Six Weeks in Russia in 1919, Ransome confessed to finding his account ‘surprisingly dull’, noting he would have liked to have conveyed more of the excitement of the Revolution which had drawn in the likes of himself, ‘far removed in origin and upbringing from the revolutionary and socialist movements in our own countries’.

‘There was the feeling, from which we could never escape, of the creative effort of the revolution. There was the thing that distinguishes the creative from other artists, the living, vivifying expression of something hitherto hidden in the consciousness of humanity. If this book were to be an accurate record of all of my own impressions, all the drudgery, gossip, quarrels, arguments, events and experiences it contains would have to be set against a background of that extraordinary vitality which obstinately persists in Moscow even in these dark days of discomfort, disillusion, pestilence, starvation and unwanted war’.

As Paul Foot notes, ‘Ransome’s writing style is as plain and clear as in any of his children’s books. His prose, in Orwell’s famous phrase, is “like a window pane”’. Ransome’s eyewitness accounts were then rather exceptional - the

Guardian socialist journalist Morgan Phillips Price also wrote impassioned reports from revolutionary Russia - and Ransome followed

Six Weeks up with

The Crisis in Russia, 1920. However, they were not reprinted after the early 1920s until the Redwords edition of 1990s – in part because the Bolshevik leaders they tended to focus on were the likes of Trotsky (Ransome fell in love with and married Evgenia Petrovna Shelepina - Trotsky’s secretary) and Ransome’s good friend Karl Radek and rather ignored Josef Stalin. As Foot notes, Ransome’s accounts had ‘shuffled him off where he belonged, to the fringe of the revolution’. Incidentally, a similar fate of neglect seems to have befallen

Louise Bryant’s accounts – despite the fame of her partner John Reed.

Foot thought

The Crisis in Russia 1920 ‘the best of Ransome’s work on revolutionary Russia’ and claims ‘the high water mark of all’ is Ransome’s ‘account of a conference at Jaroslavl'.

'He went there in early 1920 with Radek, recently released from prison in Germany…The conference was a long and difficult one and Ransome and his friends were glad to retire that night to their hotel. As they prepared for bed there was a knock at the door. A railwayman stood outside, begging them to come to a performance of a local play written and performed by local workers and their families. Ransome’s description of what follows – especially his account of Radek’s speech to the railwaymen and their families, is an electrifying piece of writing. I read it first in 1976, and return to it again and again when I feel dispirited.‘

According to Ransome, Radek was asked to ‘give a long account of the present situation of Soviet Russia’s foreign affairs'.

'The little box of a room filled to a solid mass as policemen, generals and ladies of the old regime threw off their costumes, and in their working clothes, plain signalmen and engine drivers pressed round to listen. When the act ended, one of the railwaymen went to the front of the stage and announced that Radek, who had lately come back after imprisonment in Germany for the cause of revolution, was going to talk to them about the general state of affairs. I saw Radek grin at this forecast of his speech. I understood why, when he began to speak.

He led off by a direct and furious assault on the railway workers in general, demanding work, work and more work, telling them that, as the Red Army had been the vanguard of the revolution hitherto, and had starved and fought and given lives to save those at home from Denikin and Kolchak, so now it was the turn of the railway workers on whose efforts not only the Red Army but also the whole future of Russia depended. He addressed himself to the women, telling them in very bad Russian that unless their men worked superhumanly they would see their babies die from starvation next winter. I saw women nudge their husbands as they listened. Instead of giving them a pleasant, interesting sketch of the international position, which, no doubt, was what they had expected, he took the opportunity to tell them exactly how things stood at home. And the amazing thing was that they seemed to be pleased. They listened with extreme attention, wanted to turn out someone who had a sneezing fit at the far end of the hall, and nearly lifted the roof off with cheering when Radek had done. I wondered what sort of reception a man would have who in another country interrupted a play to hammer home truths about the need of work into an audience of working men who had gathered solely for the purpose of legitimate recreation. It was not as if he sugared the medicine he gave them. His speech was nothing but demands for discipline and work, coupled with prophesy of disaster in case work and discipline failed. It was delivered like all his speeches, with a strong Polish accent and a steady succession of mistakes in grammar.

As we walked home along the railway lines, half a dozen of the railwaymen pressed around Radek, and almost fought with each other as to whom should walk next to him. And Radek, entirely happy, delighted at his success in giving them a bombshell instead of a bouquet, with one stout fellow on one arm, another on the other, two or three more listening in front and behind, continued rubbing it into them until we reached our wagon, when, after a general handshaking, they disappeared into the night’.

One gets there a glimpse of the real hope of a new world emerging out of the old - a new world workers felt was their own and were prepared to fight and die to defend - but also the utter tragedy of the counterrevolution under Stalin, where such a spirit of public service, sacrifice, work as not something associated with alienated toil but freedom, was taken up by the Stalinist bureaucracy and used to build – not international socialism – but state capitalism in the most disgustingly bloody, hypocritical and cynical manner.

No wonder Ransome by the late 1920s was sickened by what he saw happening in Stalin’s ‘new civilisation’,– and embarked instead on his legendary series of children’s stories –

Swallows and Amazons,

Swallowdale and so on. Paul Foot takes up the question which inevitably arises:

‘Was there any link at all between his delightful tales of middle class children in the Lake District and in Suffolk and the great events which shook the world in 1917? There is perhaps a clue in something wrote when he was only 22. Hugh Brogan recounts:

“The essence of the child, he held, is its imagination, the way in which, left to itself, and not withered by obtuse or manipulative adults, ‘it adopts any material at hand, and weaves for itself a web of imaginative life, building the world again in splendid pageantry, and all without ever (or hardly ever) blurring its sense of the actual”’

‘This combination of the unleashing of the imagination without ever losing grip on reality is the hallmark of Arthur Ransome’s marvellous reports from revolutionary Russia...The Russian Revolution is not just the most important event of the 20th century. It is a beacon for the 21st. For English-speaking socialists there is no more eloquent or accurate assertion of that than these passionate essays by one of the century’s great writers.

“Let the revolution fail” wrote Arthur Ransome in 1918. “No matter. If only in America, in England, in France, in Germany people know why it has failed, and how it failed, who betrayed it, who murdered it. Man does not live by his deeds so much as the purpose of his deeds. We have seen the flight of the young eagles. Nothing can destroy that fact, even if, later in the day, the eagles fall to earth one by one, with broken wings”.

Labels: Marxism, Russia, socialism