Today we imagine ketchup as the ultimate modern American food (and it is true that we like to put ketchup on…well, a lot of things). But ketchup’s origins are found in Asia, and its adaptation into the thing that resembles our thick, modern-day ketchup began in early modern Britain.

The word “ketchup” is borrowed either from the Chinese language (kôe-chiap, a brine of pickled fish or shellfish, with “kôe” as a kind of fish, and “chiap” as juice or sauce), and/or from Malay (with “kecap” or “kicap,” soy sauce). It’s likely that Britons encountered this tasty sauce – a thin, black-brown liquid that was either a type of fish sauce or a type of soy sauce – during acts of travel and colonization.

Ketchup (which early modern Britons spelled a lot of different ways: ketchup, katchup, ketchop, katchop, kitchup, ketsup, catchup, cachup, catchop, and even catshup) began to appear in British texts at the end of the seventeenth century.[1] These were sometimes travelogues and books about colonization, with a description of the sauce – and how good it tasted – but without any instructions on how to make it. When ketchup did start to show up in recipe books, it was often listed as an ingredient, but again, without providing readers with a guide on how to produce it themselves. This might mean that the recipe book authors trusted that their readers would be able to purchase ready-made, imported ketchup.

But ketchup was either so popular, so hard to get, or so expensive, that early modern British people soon started trying to make their own. Evidence for these early ketchup experiments can be found in manuscript recipe books from the period. In their quest to replicate the umami flavor found in soy- or fish-based Chinese or Malay sauces, Britons turned to a variety of ingredients: mushrooms, anchovies, oysters, walnuts, and even horseradish. One 1693 recipe for “Cucumber Catchup” called for cooks to “put a handful of scraped horseradish” to “every quart of the Liquor” in the dish.[2]

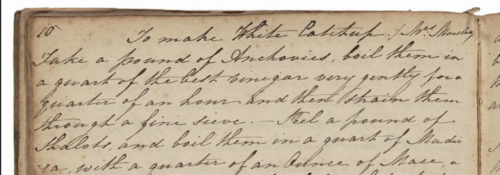

Like that cucumber ketchup, most early modern British ketchups were heavily flavored, seasoned, and spiced. Mrs. Marshall’s “white Catchup,” found in Jane Staveley’s 1693/4 handwritten recipe book, called for “a pound of shallots…a quart of Madira, a quarter of an Ounce of Mace, [and] a quarter of an Ounce of whole white pepper.” Staveley – or someone in her household – clearly liked ketchups, because her book also contained receipts for oyster ketchup, made with lemon peel, a quarter of an ounce of mace, a quarter of an ounce of cloves, and one sliced nutmeg.[3] Spices were also added to a recipe “to make catchup of Wallnut [from] Mrs Richmond” which is found in an anonymous recipe book from c. 1720. This recipe author included a quarter of an ounce of mace, a quarter of an ounce of cloves, a quarter of an ounce of nutmeg, and a little bit of pepper to their ketchup, which was supposed to be cooked until “it’s the Couler of Clarett.” Another recipe in the same anonymous book claimed that ketchup could be made spicy by using Dianthus caryophyllus, the clove gillyflower – also known as the clove carnation – as a base. This Carnation Ketchup called for the “top of three clove gilly flowers” along with one nutmeg, half an ounce of cloves, half an ounce of mace, half an ounce of cinnamon, and one shallot. This combination of botanicals created a mixture so potent, the author warned, that “a little of this goes a great way.”[4]

Longevity was another important factor. One of Mrs. Knight’s 1740 recipes for ketchup was entitled “to make catchup to keep 20 years.” This effect was apparently achieved by using “strong stale bear [beer]…the stronger and staler the bear [beer] the better.”[5]

Flavor, spice, and shelf-life were clearly important to early modern British ketchup-makers as they attempted to replicate the soy and fish sauces that had come to them via acts of travel, conquest, and colonization. But just as these Britons worked to use and enjoy Chinese and/or Malay sauces, they simultaneously adapted them, changing the recipes to suit their own tastes, needs, expectations, and palates.

Recent works by scholars of early America and the Atlantic world have traced how white Europeans appropriated, gleaned, bought, and stole knowledge and knowledge-systems from indigenous Americans and enslaved people of African descent in acts of colonization; two Recipes Project posts by Claire Gherini describe these acts via cures for poison. These frameworks can be exceptionally useful for anyone analyzing culinary adaptations made by British recipe authors. Jane Staveley explained to her friends and family members that, if “you wish” her “white Catchup” could be “thicken’d with flour and butter,” using a technique that was “the same as if you were melting butter.” In her aim to produce a sauce that, she believed, was a good accompaniment “for [the] Turkey Fowls & Veal” that often appeared on British tables, she worked to turn southeast Asian ketchup (in its place of origin a thin, salty, vinegary sauce) into British ketchup (now a dense, creamy sauce). These instructions, for making ketchup into something it wasn’t – thick, not thin; buttery, not astringent; white, not brown – were an admittedly minute act of colonization, but they were a symbolic one nonetheless.[6]

It wasn’t until the nineteenth century that Anglo-Americans began to incorporate tomatoes into their ketchup, making antecedents of the thick, red paste that we slather on fries, burgers, and hotdogs today. But as we have seen, as early as the seventeenth century, early modern British women were colonizing condiments in the pages of their manuscript recipe books.

[1] “Ketchup, n.,” OED Online, March 2019, Oxford University Press, accessed April 10, 2019, http://www.oed.com.proxy.wm.edu/view/Entry/103080?rskey=SEQwHQ&result=2&isAdvanced=false.

[2] Jane Staveley, Receipt book of Jane Staveley, 1693-1694, V.a.401, Folger Shakespeare Library.

[3] Jane Staveley, Receipt book of Jane Staveley, 1693-1694, V.a.401, Folger Shakespeare Library.

[4] Anon., Cookbook, c. 1720, W.b.653, Folger Shakespeare Library.

[5] Mrs. Knight, Mrs. Knight’s receipt book, c. 1740, W.b.79, Folger Shakespeare Library.

[6] Jane Staveley, Receipt book of Jane Staveley, 1693-1694, V.a.401, Folger Shakespeare Library. For some recent studies of the ways that European scientists and natural philosophers (both amateur and traditionally-trained) appropriated, stole, managed, and bought information from indigenous Americans and African-descended people, many of whom were enslaved, see Christopher Parsons, “The Natural History of Colonial Science: Joseph-François Lafitau’s Discovery of Ginseng and Its Afterlives,” William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 73, No. 1 (January 2016); Kathleen S. Murphy, “Collecting Slave Traders: James Petiver, Natural History, and the British Slave Trade,” William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 70, No. 4 (October 2013), 637-670; Science in the Spanish and Portuguese Empires, Daniela Bleichmar, Paula De Vos, Kristin Huffine, and Kevin Sheehan, eds. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009); James Delbourgo and Nicholas Dew, Science and Empire in the Atlantic World (New York: Routledge, 2008).

2 Replies to “Colonizing Condiments: A (Very) Short History of Ketchup”