I am grateful to Maaike Matelski and Marion Sabrié for their support and guidance throughout the preparation of this paper. I also wish to thank Benjamin and Douglas Forbes for their suggestions; and Yadana Than Htaik, Susanne Kempel, Helene Maria Kyed, and Sue Mark for important factual inputs.

1Myanmar is unusual among Southeast Asian countries for the frequency of its shifts between political and economic systems since independence. In modern post-colonial history, it has experimented with representative democracy, socialist dictatorship, capitalist dictatorship, and is now transitioning towards a capitalist democracy. By embracing a capitalist economic model in the late 20th century and subscribing to a democratic form of governance in the early 21st, the country is poised for a new merger with the global economic system. The country’s increasing rate of urbanization is one by-product of this merger, as discussed in this paper. Urbanization presents both problems and opportunities to Myanmar, as it does elsewhere in the world. Therefore, it is important to provide policy makers and the people of Myanmar with knowledge which can form the basis for making decisions that will take advantage of the opportunities while coping with the problems.

2Little research on urban Myanmar was published prior to 2015, and accessible official data is still lacking. Myanmar was politically isolated from the West for decades and thus developed almost outside of the mainstream global economy. It is often said that because of Myanmar’s delayed development, it can now take advantage of a wealth of “lessons learnt” from countries around the region and elsewhere that have already travelled this path. However, because of the country’s unique trajectory, it would be wise not to try to apply these lessons wholesale to the Myanmar context. Instead, in-depth research is especially needed at the local level to inform the strategies of individuals and communities, as well as public policy for coping with rapid urbanization and growth of informal settlements.

- 1 The questionnaire consisted of multiple sections including basic household information, condition o (...)

- 2 I concluded that in-depth interviews were the best way to access potentially sensitive information (...)

- 3 These are quasi-governmental voluntary positions. Neither position is on the government payroll, bu (...)

3This paper draws upon the same primary data that I gathered for an article published in the Independent Journal of Burmese Scholarship in 2016. The secondary sources, however, are different. There has been a wave of new material produced since 2016 on this topic, including the thirteen sources included in the bibliography of this paper. I first engaged with the topic of urbanization in Yangon while working for UN Habitat in Myanmar during the period 2010-2014. That interest led to my accepting a year-long fellowship (2015) through Harvard University which enabled me to examine the issue in greater depth. During that year, I conducted 38 household interviews across four townships with the assistance of a translator. Every household that had a resident at home at the time of the visit was approached in a target area selected at random from the larger informal settlement area using a satellite image. The “semi-structured” household interviews1 averaged just over one hour in length and generally took place inside homes upon invitation of the interviewee.2 I also interviewed key informants including representatives of international and local non-governmental organizations working in the studied townships, YCDC (Yangon City Development Committee) officials at township and central levels, a Ward Administrator, two heads of 100 households (ya ein hmu) and three heads of 10 households (seh ein hmu).3 Since 2015 I have also been a consultant on projects pertaining to informal settlements in Myanmar and homelessness in the United States.

- 4 In mainland SE Asia, Cambodia is the least urbanized (23%) and Myanmar the second least (30%) accor (...)

4Although it is still the main city of one of the least urbanized countries in Southeast Asia,4 Yangon, the cultural and commercial capital of Myanmar, has seen a marked increase in migration from other parts of the country in recent years, and the boom in new construction of high-end residential and commercial buildings is very visible (Sabrié 2019, this volume). Additionally, many Burmese exiles have returned to the country since the political reform, especially to Yangon, and with them, more foreigners have entered to take advantage of economic opportunities enabled by the reforms. These returnees and foreigners constitute only a small percentage of new arrivals to Yangon, but they have a disproportionate impact on the economic landscape because of the money they bring with them. The arrival of wealthy new residents and businesses and the foreign investment in commercial and residential real estate work in concert to drive up property values and the cost of living for everyone in the city.

5For reasons that will be detailed in the next section, Yangon is the top destination for internal migrants, and Yangon’s peripheral townships receive the majority of new arrivals. But not all of Yangon’s in-migrants are coming from outside. A smaller, but significant portion is migrating to the peripheral townships from central Yangon. These are low and middle income renters whose incomes could not keep pace with the rapidly rising rents and cost of living that have taken hold of inner Yangon in recent years. This paper will examine the various migration trends that contribute to “urbanization” in and around Yangon today. There are circumstances in the place of origin that compel persons to move away, and there are situations desired in the place of destination that draw migrants in. Both emigration from rural areas to the urban periphery and emigration from the city center to the urban periphery will be discussed in light of the costs and benefits of migration, both to the migrants themselves and to the city as a whole.

6Even though Yangon—as any city—depends on a supply of unskilled labor, and as in other developing countries much of that labor is provided by the residents who have settled informally, the historical practice of the government has been to clear squatters from central Yangon and relocate them to the new towns at the periphery (Lubeigt 2008; Sabrié 2019, this volume). This practice is problematic due to the trauma that eviction causes, the government’s inability to extend basic urban services to the peripheral areas, the increasingly unbearable commute times for those who have been relocated, and potential political consequences for the now formally democratic government.

7Many factors contribute to the precariousness of life in informal settlement areas, including underemployment, lack of proper sanitation, crowded conditions, natural and industrial hazards, and of course tenure insecurity itself (see also Kyed 2019, this volume). By direct observation of the author, these factors are common to informal settlements throughout the developing world, and Yangon is not alone among Southeast Asian cities where informal settlements are distinguished by the near constant threat of eviction (Korff 1996), and high levels of indebtedness (for example Jakarta, or Phnom Penh [Blot 2014]). Taken together, these factors contribute to a growing crime rate, which has been discussed in detail in at least two recent studies (Freeman et al. 2017; Kyed 2017) Exploration of these subjects is both important and timely due to the rapid rate of in-migration and growth of informal settlements happening in Yangon today.

8Based on field research, this paper argues that most sensible locations for informal settlements, both for the settlers themselves as well as for the city as a whole, are neither in the central business district (CBD) nor the periphery, but in the “Central City” area in-between. Here there is proximity to middle class neighborhoods where there are work opportunities in “helper jobs” (e.g. cooking, cleaning, maintenance, security) while other members of the household can also easily commute to the industrial zones in the periphery for work. Meanwhile the marketplaces, hospitals and other services of the CBD and sub-centers are not too far away thanks to the Circle Line train and BRT (Bus Rapid Transit). These “Central City” locations often take advantage of existing infrastructure by “pirating” electricity and water from wires and pipes traveling through or alongside the settlement on their way to adjacent neighborhoods. Finally, the smaller pockets of settlements found here tend to have healthier community spirit and lower crime rates, compared to the larger informal settlement areas common in the periphery.

9The monetary value of land in urban areas increases with the growing demand for land by high-end residential and commercial developers. UN Habitat also notes that several new laws passed since 2011 have eased the process of land acquisition, allowed the establishment of Special Economic Zones (Special Economic Law, 2014); provided for the conversion of farmland to other uses (Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Land Act, 2012); and have legalized the transfer, exchange and lease of land (Farmland Act, 2012) between individuals with land use rights. These laws have increased the demand for both rural and urban land. In urban areas, this has also contributed to the increase in cost of rental housing. New high-income jobs have emerged for skilled professionals who are willing and able to pay more for the convenience of residing near the downtown area. The eviction of squatters becomes a by-product of this process and it usually falls on city authorities to carry out the “dirty work” (Korff 1996).

10Yet there is simultaneously a greater demand for low-skilled workers to satisfy the demands for services and goods of the new middle class and high-income employees in the city center: “the availability of inexpensive services provided by security guards, cleaners, maids and so forth” (Korff 1996: 293). The availability of cheap labor in developing countries attracts foreign investment in the city and its periphery. Korff refers to the “metropolitan dilemma” when “low income employees have to reside closer to their places of employment in city centers on potentially valuable land, as travel from distant places would be too expensive and time-consuming”. Squatting in or near the city center could be one “solution” to the urban dilemma, but it comes with a critical risk: eviction. This risk has been fully realized in central Yangon, where most squatters have already been removed.

- 5 From 1985-9 there were 1106 fire outbreaks in these areas which led to the destruction of 7737 dwel (...)

- 6 Data from YCDC (2012). Dagon Seikkan has the highest percentage of households with living spaces le (...)

11In this paper, the term “slum” refers to an informal settlement area where residents not only lack legal claim to their land or housing and lack basic urban services, but also live in precarious conditions and are at risk of eviction. Such settlement areas in Yangon are frequently prone to flooding during the rainy season (which is nearly half the year), and due to their crowded conditions, use of highly flammable building materials (e.g. thatched roofs) and use of wood for cooking fuel, they are also prone to fire in the dry season.5 Typically, slum dwellers stay in substandard housing with over five family members living in a one room hut (the average in this study was 5.4, compared to the Yangon average of 4.4 members per household6). A hut is typically 15 ft. by 20 ft. Conditions may be visibly squalid with open garbage dumps and inadequate latrines resulting in foul odors. Pit latrines are generally used but rarely maintained. Most residents let them fill up until the rainy season when flood waters clear out the latrines’ pits or holding tanks, resulting in very unsanitary conditions.

12Estimates of the numbers of informal settlement residents in Yangon range from 270,000 (JICA and YCDC 2013), 365,000 (UN Habitat 2017), 400,000 (Myint 2017) up to 1 million (Dobermann 2016), and 1.8 million (Ye Mon 2016). Part of the reason that there is such a wide range of estimates may be lack of agreement on what constitutes an “informal settlement”. In particular, a distinction should be made between squatters who live in slums and fear eviction (who form the focus of this study) and people who live in violation of zoning or business codes in one way or another. The latter is a much larger group, up to three times as great as the number of squatters discussed in this paper. They are people who live in homes built on illegally subdivided private land, homes in violation of zoning ordinances, apartments that are unauthorized additions to existing structures, structures in violation of building codes, and so forth. However, since these residents generally face no threat of eviction, discussion of their condition falls outside the scope of this article.

- 7 Myanmar is not the first country to use eviction as a means to political ends. The most famous in t (...)

13The rate of rural to urban migration is on the rise and the prospect of Yangon’s population doubling within the next 20 years (JICA/YCDC 2013) is disturbing given the current state of urban problems (traffic congestion being only the most obvious). Yet it should be remembered that during a nearly equivalent period of time, from 1941 to 1965, the city’s population tripled. The area of the city expanded dramatically, and mostly towards the north due to the physical restrictions of rivers and swamps in other directions. The first major slum clearance of inner-city Yangon occurred in the late 1950s. The population of lower Myanmar had been swelling since the late 19th century due in part to increased production of rice and the corresponding increase in the demand for labor in the Yangon and delta regions. Following World War Two and independence, many rural areas were affected by political instability and conflict, which resulted in a further influx of people seeking security in the urban centers. Correspondingly, the squatter population also increased. Rangoon’s squatter population, said to be 50,000 in 1951, was over 300,000 by 1958 (Than Than Nwe 1998). While previous governments had hesitated to move squatters involuntarily, the new military regime moved nearly one third of Rangoon’s population to three new satellite townships in the late 50s and early 60s (Yin May 1962). Sites-and-services plots were created in the satellite townships of South Okkalapa, North Okkalapa and Thaketa to accommodate the relocation of these squatters. At the time, these townships were at the periphery of the city. UN Habitat reported in 1991, that a total of 60,000 plots were provided, and although they suffered from inadequate services, especially drainage and sanitation, they had merged into the socioeconomic fabric of the city. The Housing Department attempted to replicate the squatter clearance and relocation of the late 1950s in the late 1980s, by which time the proportion of squatters in the inner city had again reached the levels of the late 1950s. Yet this second relocation seems to have been more rushed and more politically motivated that its predecessor. In the wake of the 1988 crackdown on political dissent, squatters living around pagodas and monasteries (which were staging points for protests) were forcefully relocated to the new townships at the urban fringe.7

14Although there are no publicly available official figures, it has been estimated that 450,000-500,000 people were relocated from the city center (Morley 2013; Mya Maung 1998). Six townships were created by the military government in the late 1980s to resettle squatters relocated from downtown Yangon: North, South and East Dagon; Dagon Seikkan; Hlaing Thayar and Shwe Pyi Tha. A total of 97,730 plots were created in these new townships, as well as in existing townships (UN Habitat 1991). Many of these relocated squatters, victims of fires and middle-class people evicted from their homes, suffered great hardship in their new semi-rural locations lacking basic amenities. In 1991 UN Habitat noted these new resettlement locations were on low-lying ground and adjacent to major waterways, making them subject to seasonal flooding. This created an ongoing hygiene problem still observed today, where pit and septic tank latrines flood in the rainy season, and contaminated water flows into residential plots. A recent informal study by UN Habitat tentatively found that Hlaing Thayar Township has the highest occurrences in Yangon of disease related to poor environmental conditions and lack of water and sanitation facilities (diarrhea, dysentery, malaria and tuberculosis).

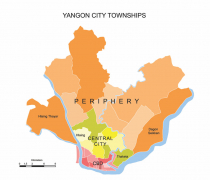

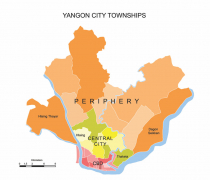

Fig. 1. Yangon ci...

Fig. 1. Yangon city townships

Source: Forbes (2018). Map: Eben Forbes, 2018.

15As previously noted, Yangon stands in contrast to regional cities in that very few informal settlements areas remain in the inner city, especially in the historical downtown area. The settlements that remain are very small, consisting of only a few households and otherwise they are comprised of port workers, railway workers, or other direct or indirect employees of government who enjoy a de facto tenure security. Squatters have been removed from the downtown area over the years to make way for the development of office buildings, hotels and apartment buildings. The new construction has intensified, most noticeably since the political opening in 2012 which was the condition for North American and European countries to rescind economic sanctions, thus resulting in a new flow of capital into the city. According to interviewees, most in-migrants settle in the periphery townships of North Yangon because of the lower cost of living there. On the other hand, West Yangon, which contains the Central Business District, has lost more than twice as many residents as it has gained (UNFPA Census Thematic Report on Migration and Urbanization 2014). Those that have moved out are largely low and middle income renters whose incomes could not keep pace with the rapidly rising rents and cost of living that have taken hold of inner Yangon in recent years. Consequently, there is movement in both directions: from the rural areas towards the city, and also a smaller but still significant movement away from the central business district. These two movements converge on the periphery.

16Outside the downtown area, the situation is somewhat different. There remain many small pockets of slums (15-60 households) scattered throughout the zone between the inner city and the periphery, in townships such as Hlaing, Kamayut, Thaketa, and Thingangyun, in an area referred to in this study as the “Central City”. This zone constitutes an especially advantageous location for low-income residents and their employers and will be further explored in the following sections of this paper.

17Of the 365-500,000 estimated squatters who live in slums and risk being evicted, very few remain in the central townships of Yangon (Forbes 2016; UN Habitat 2017). The largest concentrations are found in townships that form the outskirts of the city. The land that can be described as the outskirts, or periphery, of the city is not delimited by a static boundary. In the 20th century the city twice expanded its boundaries, each time creating new townships to accommodate the resettlement of inner-city squatters. A 2016 UN Habitat survey found that nearly all informal areas settled since 2010 are located in the urban periphery. When compared with other cities in Asia, Yangon has fewer squatters overall, less than 20% of the city’s population, whereas the average in Asia is 30% (Habitat III 2015). Also, more of Yangon’s squatters reside in the periphery as compared with the other Asian cities.

18The liberalization of Myanmar’s economy—first in the 1990s and now more profoundly since 2010—has led to the expansion of export-oriented industrial zones in the city periphery, drawing low-skilled workers from the countryside. The expansion of these zones has coincided with several rural trends: nationally, there are a growing number of landless farmers due to distress sales by heavily indebted farmers, land-based speculation, land confiscations, and concentration of land into larger-scale holdings. Without their own land, these farmers are more likely to migrate in search of new opportunities. Sometimes farmers migrate to other rural areas to find better conditions (World Bank 2016) but for the sons and daughters of farmers, urban areas are becoming the preferred destination. Yangon is a big draw for unskilled in-migrants from rural areas, especially the Ayeyarwady Delta—the Region adjacent to Yangon Region and from which Yangon City receives the most migration. Here there are increasing numbers of landless farmers who face a meager existence working other people’s fields for very low wages in seasonal planting and harvesting work. In some Delta villages as many as 75% of young people have migrated (Myanmar Times 2016). Interestingly, local urban centers in Ayeryawaddy Region are seeing a decline in population, which shows that Delta migrants are not heading for their regional towns and cities in search of opportunity but prefer Yangon instead (Tin Yadanar Tun 2017). It is not difficult to understand why Yangon attracts so many migrants, not only from adjacent rural regions, but from other states and regions across the country. On most social development indicators, the Yangon Region scores well above the national average (UNDP Myanmar 2015). Thanks to mass media and word of mouth, migrants are aware that there is generally a higher standard of living in Yangon as compared with the rest of the country. Some migrants I interviewed had seen television footage of construction projects and had heard accounts of construction job opportunities. Studies have shown (Boutry et al. 2016; World Bank 2016) that the proliferation of inexpensive SIM cards and mobile phones that began in 2013 has improved communication between rural dwellers and family and friends in the city. Given the expense and risk inherent in uprooting from the countryside and moving to the city, communicating by phone with “pioneer” family members or former neighbors who have already made the move is an indispensible tool for learning about the availability of jobs and housing prior to undertaking the journey. Thus, through word of mouth, villagers are informed about the proliferation of industrial zones on the city’s periphery.

19In terms of cost of living, moving to the periphery makes sense for low income people, as it does for landlords in the CBD who can charge higher rents after low income tenants are priced out; not to mention investors and developers who can build higher value commercial and residential properties once low income residents leave and squatters are cleared from neighborhoods in and near the CBD, and export-oriented industrial zones get an easily accessible surplus supply of cheap labor. However, for workers who need access to central Yangon or its sub-centers, settlement in peripheral townships results in long commute times, which are a huge burden in terms of both time and money.

20Lubeigt (2008) explains that many factors have led to population growth at Yangon’s periphery. In addition to relocating squatters for political reasons, there were economic incentives to clear them out of the downtown area to make way for higher-value developments. The government also relocated cottage industries out of downtown residential neighborhoods to improve living conditions and as part of a larger strategy to consolidate industry at the periphery. The government chose Yangon’s periphery as the site for boosting industrial production which also necessitated increasing the supply of inexpensive labor at the periphery,

[…] the construction of factories since the beginning of the 1990s had been quite limited and insufficient to provide many job opportunities for the civilian population. Therefore, with a growing population in search of a living, the gap between unemployment and job opportunities increased dramatically. The newly designed industrial zones were intended to bridge this gap. (Lubeigt 2008: 161.)

21By 2013, according to the JICA/YCDC Master Plan, Hlaing Thayar had 868 factories and workshops. Factory jobs are one of the “pull factors” that lure migrants from rural areas, especially landless farm laborers whose work is very seasonal. The prospect of a job that offers stable employment year-round is very appealing to this group who has little or no income for many months of the year on the farms. It is no wonder that they would choose to squat near to the factories to avoid high travel costs. A study in neighboring Htantabin Township (Boutry et al., 2016) interviewed factory workers who regarded their new jobs as “clean” (than) and more “civilized” (yin kyay) compared to having to work in the muddy fields under the rain or under the sun. Yet my own field research found only a small minority of squatters benefitted directly from factory jobs (Forbes 2016). None of the respondents in my study had a regular, formal factory job, and few even knew of someone in their ward who held such a job. One woman interviewed worked temporarily at a factory; another sold food to factory workers. Respondents said that factory jobs had a minimum educational requirement that put these jobs beyond their reach, or that factories only hired workers between the ages of 18-25 and in perfect health. So, although the new industrial zones attract migrants, they still do not seem to be supplying the hoped-for regular jobs. Instead, most informal residents of Hlaing Thayar only benefit indirectly, by providing services sold to factory workers such as ready-made food.

22On the urban periphery, my research focused on the townships of Hlaing Thayar (pop. 700,000) and Dagon Seikkan (pop. 120,000) because they currently have the largest informal settlement populations at 124,325 and 45,405 residents respectively (UN Habitat 2017). The field research in Dagon Seikkan focused on Ward 67, due to news of an impending mass eviction. In 2015, the Department of Human Settlements and Housing Development was planning 900 units of what it called “affordable housing” on a site occupied by 1,500 informal dwellings in Ward 67. At $ 20,000 each, these housing units were affordable to some people, but not to any of the residents interviewed in the research area of 1500 households anticipating eviction. A relocation site was designated for the evictees (interview, YCDC Urban Planning Unit) though it is both smaller and further away from central Yangon than the current Ward 67. Furthermore, only squatters in residence for 10 years or longer have been considered for resettlement. No services have been provided at the new site, but a titling program was said to be in the works.

23The households I surveyed in Dagon Seikkan reported migrating from rural and urban areas in equal numbers. Many moved from Dawbon or Thaketa Township (townships closer to Yangon center) when development in those townships caused rents to rise. Some were evicted from Thaketa, some were priced out of the rental market, and others had to give their land to a moneylender when they could not pay their debts. Most of the migrants from rural areas came from the Ayeryawaddy Delta; at least a few of these were displaced by Cyclone Nargis in 2008.

24Hlaing Thayar is the fastest growing township in Yangon in terms of both formal and informal settlement populations. Hlaing Thayar Township was created in 1993 to house squatters relocated from downtown Yangon. The new residents received land but no services, and few received formal land use rights. Over the years, some of those who were relocated here in the 1990s have gained a measure of tenure security, and most have gained access to electricity and garbage collection in the intervening decades (Kyed 2017). Moving forward to the present day (Forbes 2016), migrants to Hlaing Thayar are more likely to come from rural areas. Arrivals from the rural Ayeryawaddy Delta have been largely responsible for the recent population growth here (Dagon Seikkan has received as many migrants coming from other urban townships of Yangon). This migration trend has been more pronounced since Cyclone Nargis ravaged the delta in 2008. Some settlements have sprung up nearly overnight—during interviews there were reports of “land invasions” or organized takeovers of land by squatters en masse.

25Little community sentiment is apparent in Hlaing Thayar, even in the informal areas, owing to the recent and highly mobile population, and the wealth inequalities observed. Several authors have researched this township extensively in recent years and the mistrust between neighbors has been documented (Than Pale 2018; Kyed 2017). Kyed notes that the criminalization of squatters by city authorities is inhibiting the development of viable forms of self-organization in Hlaing Thayar (Kyed 2017). Than Pale notes that the informal settlement areas of Hlaing Thayar lack access to both formal judicial mechanisms because they are unregistered, and informal dispute resolution because of the breakdown of social interconnectedness (Than Pale 2018).

26Wealth inequality is not only a feature of the peri-urban townships on the whole, but also within the informal settlements of Hlaing Thayar and Dagon Seikkan. The standard of living is much higher for residents who control water supply sources (wells, pumps and distribution networks), as well as for those who control sources of electricity such as generators. Heads of 100 households have a financial advantage over their neighbors due to profits from informal real estate transactions. Greater wealth is also visible among those who reside alongside the main roads in the settlements as these huts double as shops and workshops that sell goods and services to other residents in the area. These services include professional lending. Several interviewees reported taking loans from these roadside residents; a fairly lucrative business given the standard 20% monthly interest charged by professional lenders. None of this should be a surprise, as such inequalities are a reflection of the larger society, and these large informal settlement areas can best be thought of as “cities within the city.” But the observation is included here to refute any presuppositions that slums are uniformly poor. Wealth inequality has also been linked to social tensions (UNDP Myanmar 2015) and crime (Freeman et al. 2017). By contrast, social cohesion was observed in the “Central City” informal areas studied and is discussed in the relevant section below.

27Similar to Dagon Seikkan, evictions are carried out regularly and sometimes on a massive scale in Hlaing Thayar. On 15 January 2014, 4000 huts built by squatters in Hlaing Thayar were demolished under orders of the divisional government (Kyaw Hsu Mon 2014). The rapid cycle of squatting and eviction in this township creates many challenges, including for researchers; it is difficult to research such a fast-moving target. But Hlaing Thayar’s dynamism makes it an ideal place to study the motivations behind migration today in Myanmar, and other researchers have been looking at the “push and pull” factors that underlie the migration to Hlaing Thayar from rural areas (Boutry 2014; Kyed 2017). As previously noted, not all new migrants are from rural areas. Some are squatters who were cleared from the inner city, and others were formerly formal owners and renters who were priced out of the inner city due to the rising rents and cost of living there.

28Thaketa Township is geographically close to downtown Yangon, situated just to the east, although access is somewhat inhibited due to having to cross the Panzudaung Creek by bridge. The township was formed when the government relocated squatters from the inner city in the late 1950s and 1960s. The relocation programs at that time were relatively well managed: 30—and 60—year leases were given to many residents, and services were provided in some places. Decades later, a new generation of squatters is springing up, and yet they were largely born and raised in Thaketa itself. Squatting in Thaketa is thus an example of what UN Habitat has called “resettlement area subdivisions” or re-squatting (UN Habitat 2017). As rents and cost of living rise in Thaketa, many households are being “priced out” of the rental housing market and are ending up as squatters within their native township. Historical imagery from Google Earth shows that many of these squatter areas came into existence during the same time period that rents doubled:

Fig. 2. Thaketa T...

Fig. 2. Thaketa Township, 2007 (left), and 2015 (right)

Source: Google Maps.

- 8 Satellite images are useful for revealing the lack of a street grid and smaller size of dwellings, (...)

29Both images show the formal neighborhood with its regular street grid, but in photo 2 (2015), an informal settlement has grown to the left of the formal neighborhood.8 At the time of field research (2015), informal areas in Thaketa were relatively small in size, comprising between 30 and 60 households on average. A noticeable sense of community unity was found in these areas, owing to their small size and longer term of residence (average of 8½ years in the location). Most of the squatters were originally from Thaketa itself, which may have helped create affinity. The threat of eviction was relatively low due to good relations with the local authorities (elsewhere fear of eviction can create divisions with longer-term squatters claiming to have more rights than recent arrivals). Finally, it may be that a greater communal sense is possible in a neighborhood where incomes are more or less equal. As previously discussed, the larger periphery settlements had a greater variation in income.

- 9 Search for Common Ground notes that “Increased levels of migration and urbanization in Myanmar lead (...)

30The sense of community here was observable in several ways. Most obvious was the way that neighbors visited each other’s huts during the interviews. Interviewees revealed that small loans were sometimes given between neighbors with no or very little interest. In one study area, the Head of 10 Households and the Head of 100 Households (the latter located outside the community) had helped residents by providing them a formal address for purposes like school matriculation. In another study location, the heads of 100 households, supported by the heads of 10 households, have taken responsibility for cleaning the area and drain clearing, by organizing volunteers. In contrast, heads of 10 and 100 households on the periphery seemed adept at leveraging benefits from their positions, but without carrying out any of the associated community responsibilities, aside from occasional dispute resolution between neighbors. Possible explanations for the difference are that the study areas in Thaketa were much smaller in size that those in Hlaing Thayar, and also, they were older and more stable: the squatters in Thaketa averaged 11 years in their current location versus 5 years in Hlaing Thayar. Due to the much larger size and higher turnover of the population in Hlaing Thayar, the informal settlement areas were less cohesive and the heads of 100 households were correspondingly less concerned with the well-being of residents. Another factor may explain the difference in community sentiment between the two townships. There is likely large significance in the fact that Thaketa squatters are almost all from Thaketa itself whereas Hlaing Thayar squatter are almost all from somewhere else, whether from another Yangon township, or another State/Region entirely. Obviously “natives” of Thaketa will have more in common with, and greater affinity with, each other than will the mélange of squatters in the peripheral townships.9

- 10 Martim Smolka (2018) refers to this as the “non-affordability paradox”.

31Another advantage to squatters in “Central City” areas was the availability of water pirated from the municipal supply. In one study area in Thaketa, the municipal water supply was right in front of the informal settlement, so access to water was both easy and free. The reservoir, about 100 yards square and 50 feet deep, was the primary water source for 5 wards in Thaketa. The water appeared very clean, containing abundant aquatic flora, and some households drank the water without boiling. This was in contrast to the periphery townships, where most water was delivered by two paid services: drinking water in large bottles at 200 to 400 kyats per day and washing water in barrels at 400 to 600 kyats per day. A little-known fact in the formal community is that the cost of water is less for formal households than for informal households in peripheral areas, because in such areas water has to be carted in containers, which is very inefficient and adds the cost of carriage to the cost of the water.10

32In Thaketa it was easy to observe that the decision to squat is a sensible choice in the vast majority of cases: almost all households interviewed here were squatting as a direct result of rising rents. They reached a decision point—they could either move out and become squatters in order to continue to have enough food and be able to pay school fees, or they could continue paying rent, but not both. If they chose the latter, then negative coping strategies would have been necessary—cutting back on food, keeping children out of school, and so forth.

33Hlaing is unlike the other townships selected for this study. It is not a resettlement township but is part of the original city of Yangon. Geographically it is another “Central City” township, as it is located north of the city center, between Inya Lake and the Hlaing River. I conducted nine interviews with squatters who had settled around an abandoned waste water treatment plant on land owned by the Ministry of Education. A distinguishing feature of this area is that it is located very near the railway station, which allows commuting to the central business district within half an hour. To put this in perspective, the trip would be well over an hour by car, due to traffic. In spite of this convenient transportation option, the most common job was laundering clothes and housecleaning in the adjacent middle class apartment buildings. In the small survey sample of nine households, five individuals were working in the adjacent middle class apartment buildings, four were working outside the ward, and three were working inside the informal settlement area itself. The authorities cleared this area every April, at which time residents would temporarily flee to the periphery (Hlaing Thayar), but would come right back as soon as it was safe to do so. The shacks were made of inexpensive materials so they could be erected again without great expense.

34There is a long history of migration from the countryside to the city in Yangon as in most other cities. But in spite of this long history, there still is a “historically embedded tendency to view all informal dwellers as strangers rather than as legitimate residents of the city” (Kyed 2017: 7). Viewing squatters as outsiders that do not belong in Yangon may serve a practical purpose for local government. First there is a widespread belief in government, including at the Yangon City Development Committee (YCDC), that granting land title or services to squatters will send a message that squatters are welcomed, and officials genuinely fear that the result would be an even larger influx of migrants to the city (interview, YCDC 2015). Secondly, eviction may be used as a tool of urban planning in Yangon as its use allows the City to build infrastructure or erect new buildings without engaging in a long process of negotiation, compensation and resettlement. Using eviction as such a tool would depend upon popular acceptance of the view of squatters as illegitimate, as outsiders that do not belong. Many observers, including this author, predicted that evictions would be less frequently used by the government after the purportedly pro-democracy NLD party swept the 2015 elections, assuming there would be a new respect for human rights. Yet the practice of eviction has continued to the present day. Perhaps the only change since 2015 are the noticeably more vocal protests by squatters who have been evicted or are about to be evicted (Sabrié 2019, this volume). An earlier study of slums in Bangkok, Jakarta and Manila notes that “with liberalization and democratization of the political process and the diversification of elite groups, more opportunities for the rise of local movements are provided” (Korff 1996: 296).

- 11 The mayor was acting on the JICA/YCDC “Master Plan” which divides the city into seven sections. The (...)

- 12 In Myanmar, land is often held as an investment and a hedge against inflation because financial ins (...)

35Government planners have only recently begun to grapple with the growth of informal settlements. In 2014 there was a new effort to create more urban land in the periphery of Yangon. In September 2014, the Mayor of Yangon announced that the city limits would again be expanded, this time by 30,000 acres.11 The Mayor was attempting to continue a decades-old government practice: to expand the city’s boundaries in order to accommodate new migrants as well as squatters relocated from informal settlements downtown. Yet in a sign that the old days of decisions taken at high levels without consultation or transparency might be coming to an end, public outcries about awarding the contract for expansion-related works without any transparency or competitive bidding process led the Mayor to suspend the expansion two weeks after it was announced. Still, the case is illustrative because even before the Mayor’s plan was made public, land prices surged in the expansion area, and speculators purchased land from farmers. With the new right to sell land handed to farmers by the 2012 Farmland Law, farmers may oblige speculators’ offers in exchange for quick cash and the right to continue farming the land until it is sold to a developer. But of course, farmers are not always fully informed about the expected high value of the land, and speculators are poised to make far more money than the farmers.12

36The Myanmar government’s approach to informal settlements, insofar as there has been a uniform approach, has been eviction, sometimes followed by relocation and resettlement. For those resettled, the government sometimes provided serviced land, sometimes not. Very few receive formal title; such a benefit has been generally reserved for civil servants. Rapid urbanization, when it happens in a developing country such as Myanmar, is very difficult for government to manage. In Yangon, YCDC is under tremendous pressure both from residents and from the Union (national) government. As a result, it has sometimes prioritized short term gains at the expense of longer term strategic planning, in order to demonstrate progress (Vaughan 2017). YCDC does not yet have a long term plan for the growing squatter population. Nonetheless, since 2016 the Municipality has at least recognized the reality of informal settlements in the city and has invited research on them. It has also committed to a long-term strategy to establish sub-centers, six in all, to reduce the need for travel to the CBD which will not only ease traffic for everyone, but also will result in less hardship for the very low income people in the periphery who need better access to health care, education and marketplaces.

- 13 The Master Plan makes only perfunctory reference to the two new land laws passed in 2012. While the (...)

37Similarly, based on the prediction that Yangon’s population will double in the coming decades, the Strategic Urban Development Plan for the Greater Yangon Area or more informally the “Yangon Master Plan”, adopted in 2015 (and revised in 2017) by the Yangon Region Parliament, proposes new areas of urban expansion. It proposes new town centers, and major investments in transportation. The Master Plan targets infrastructure, particularly transportation, water supply, and garbage disposal. However, it does not address land use planning which is at a greater level of detail.13 Land use planning is a process whereby land for low income people in need of housing should be identified for future development.

38For the benefit of both skilled and unskilled workers, clearly transportation needs to be improved as well, and the Master Plan included a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system which was introduced in February 2016 with two circular routes that cover Yangon’s two main arterial roads. Although the BRT does not yet serve Hlaing Thayar or Dagon Seikkan, it is an important first step in lessening commuting time citywide, as is the upgrading of the circle line train which is currently underway.

39There can be unintended consequences to every decision taken on informal settlements. Experienced city planners know they must carefully think through all scenarios before acting, and implement safeguards to mitigate unintended consequences. While a close reading of the newspaper is enough to reveal that eviction normally results in squatting by the same people at new locations, other aspects of informal settlements are much less obvious. Upgrading a slum, for instance, can lead to rise in the land value which creates risk of elite capture by slumlords (informal landlords) who may simply raise the rent if a slum area is upgraded, forcing the poorest renters to move. Along the same lines, the offer of a relocation package to long-term squatters can lead to a sudden increase in squatting in the same area by new squatters who may think they can get in on the deal.

40YCDC and GAD (General Administration Department) are the two government entities that are most relevant to the discussion of governmental response to rapid urbanization and growth of informal settlements. Several sources discuss the different and overlapping roles of YCDC and GAD (Kyed 2017; UNDP 2015). The lack of clarity between the roles of the YCDC and GAD has hindered government action on urban challenges. More generally, the governance structure in Myanmar has been criticized as overly “hierarchical and compartmentalized” (Dobermann 2016: 16). The lack of communication between departments belonging to different ministries, and the lack of autonomous decision making by lower level arms of the government has negatively affected government responses to urbanization at the local level.

41There are other features of urban governance in Yangon that deserve mention as well. In 2014, YCDC was expanded from five to nine members after the first ever elections of city council members. Now half the members of the City Council are elected, and the other four are appointed by the Yangon Region government (UNDP 2015). The Mayor is appointed by the President of Myanmar, and the other Council members are appointed by the Yangon Region government. In spite of being an appointee, the Mayor does not report directly to any Union Ministry, which affords his office some autonomy. Nonetheless, more popular representation in municipal government would increase public confidence. The YCDC is financially self-sufficient, raising its own revenues through tax collection, fees, licenses and property development, but its budget is controlled by the Region Hluttaw (regional parliament). Also, tax revenue would increase dramatically if it were based on properties’ market value, and not simply its acreage; yet a tax system based on market value would require a fully functioning digital land registry (Dobermann 2016). All told, the YCDC’s relative autonomy puts it at the forefront of the move towards decentralization of government in Myanmar, and as such plays a key role in the development of Myanmar’s quasi-federal system.

42The factors pushing rural dwellers towards Yangon include the poor economic conditions of landless farmers in the countryside who have suffered stagnating wages and seasonal unemployment. These migrants come to Yangon seeking more stable, year-round employment. Some have also come to Yangon seeking improved healthcare and education, and may have fled drought or environmental disaster. For instance, in the aftermath of Cyclone Nargis, many former delta residents fled their homes and farms and sought safety, food, shelter, and new livelihoods in Yangon. Given that landlessness was also high in the delta, it is unsurprising that most households interviewed in Hlaing Thayar originated from the delta.

43While the households interviewed in periphery townships were more likely to originate from rural locales, the majority of households interviewed in “Central City” townships were from other inner city areas. The “push” factors of eviction and rising rents predominated in Thaketa, while the “pull” factors of better work, healthcare and education predominated in Hlaing.

44Overall, migration was somewhat more frequently the result of negative events that occurred in the place of origin (government relocation/slum clearance, poor conditions or natural disaster in the rural area, etc.) rather than by factors that would normally attract or “pull” rural dwellers into the city: employment prospects, better access to services, and so forth. Nonetheless, all townships studied presented a mixed picture of urban and rural origins and both pull and push factors were at play in motivating migration.

45My research found the “Central City” to be a preferable location for low income migrants because of the better transportation options and improved access to water and electricity supply. The improved transportation in the “Central City” townships was largely the result of access to the circular train line in Hlaing Township which cut travel time to the central business district by more than half. There was better access to marketplaces (for either selling their wares, or sourcing wholesale goods) and hospitals (in the case of serious illness, complicated pregnancies, etc.) compared to the periphery. Interestingly, despite the better transportation options, only about one in six of the “Central City” respondents travelled outside their township for work, whereas the figure was about one in three for respondents in the periphery. This is due to “Central City” squatters having more opportunities for work in immediately adjacent middle-class neighborhoods. Middle class neighborhoods were not usually in such close proximity to informal settlement areas in the periphery. On the other hand, access to neighborhood clinics and schools was mostly the same for each location.

46None of my respondents had a regular factory job in the periphery in spite of the presence of industrial zones there. The research found many who could be said to be benefitting indirectly from the presence of these industrial zones and their workers, by vending food to factory workers, for example. In focus group discussions, the question was posed of why there were not more people working regular factory jobs. The response was that these jobs have a minimum educational requirement that puts them beyond their reach and that factories only hired workers between the ages of 18 to 25, and in perfect health. A 2016 report by the International Growth Centre assessed that skilled workers are in too short supply throughout the country. A technical and vocational training law is being considered by the Union government, but meanwhile matriculation is low at training institutes because there are not enough qualified prospective students. But where is everyone working if not in the factories? More often than not, they are selling goods and services to each other. In this way the informal settlement on the periphery is like a “city within the city”, with its own informal economy. Much of employment is generated by the informal settlement itself: vendors sell produce and goods to other squatters in neighbourhood markets, water distributors, money lenders and informal real estate brokers. In fact, the financially better off squatters engage in precisely these activities. They own the wells and pumps and enjoy a local monopoly on water. They lend money to other squatters- a service for which there was continuous demand. So, while the industrial zones may attract migrants seeking regular year-round employment, this research casts doubt on whether the zones are meeting expectations with the actual supply of regular jobs. Instead, the results of this research suggest that proximity to middle-class neighborhoods was more strongly correlated with steady employment opportunities for this population than is proximity to factories. In both of the “Central City” townships studied, there was a high incidence of employment in “helper jobs” in service to middle-class residents; maids, security guards and the like.

47The decision to squat is usually a sensible choice: many households interviewed were squatters simply as a result of rising rents. The decision point for many came when they could either move out and become squatters with enough food and be able to pay school fees, or they could continue paying rent, but not both. In spite of the reports of “professional squatters” around the city, and the existence of higher crime rates in Hlaing Thayar, squatters in Yangon are generally not criminals. The great majority are poor people who have made the understandable decision to pay less for housing in order to spend more on food and other necessities. Understanding their logic can help authorities to work with squatters rather than at odds with them, in the search for solutions.

48Solutions will generally arise only after squatting is understood as a respectable choice for many poor people, and from taking the strategic view of low income families as an economic asset to the city, rather than a burden. By incorporating squatters and other low income families, the formal city benefits from a large pool of labor and micro-businesses. Including them in the formal city would reap important benefits for social cohesion, service delivery and employment creation.