A key moment in the rise of the modern U.S. far right took place in the early 1980s, when many white supremacists went to war with the U.S. government. Bring the War Home is a valuable but flawed treatment of this history.

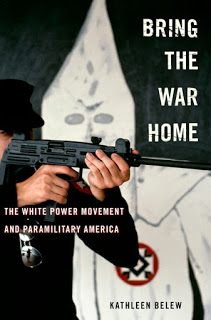

Kathleen Belew’s 2018 book Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America traces the roots and development of a white supremacist revolutionary underground in the United States, covering the period from the late 1970s to the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. Belew, a history professor at the University of Chicago, has put a decade of research into this book, and she gives valuable accounts of Ku Klux Klan activism in Texas in the 1970s, the 1979 Greensboro massacre of leftists by a coalition of Nazis and Klansmen, U.S. white supremacists’ involvement with mercenary networks in Central America and elsewhere, and movement activists’ pioneering use of computer bulletin boards in the early 1980s. Bring the War Home provides a lot of detail that was new to me, and corrects at least one significant error in my own work. (In Insurgent Supremacists I described the prison-based Aryan Brotherhood as “primarily a criminal syndicate rather than a political organization,” but Belew argues persuasively that the organization was an important supporter of Aryan Nations in the 1980s, supplying both men and funds.)

What makes Belew’s book especially valuable is that it centers on the shift by many white supremacist groups from “vigilante violence,” which reinforced the existing state and related hegemonic structures, to “revolutionary violence,” which sought to overthrow the state (x, 106-107). The shift was spearheaded by the underground organization known as the Order, which formed in 1983 and carried out a series of killings, robberies, bombings, and other illegal activities over the next two years, but also involved several other paramilitary groups, such as the Carolina Knights of the Ku Klux Klan/White Patriot Party; Arizona Patriots; and Covenant, the Sword and the Arm of the Lord; as well as support and feeder organizations such as Aryan Nations. As Belew notes, the rise of these groups “has often been misunderstood as a simple resurgence of earlier Klan activity” (8), when in fact it represented a dramatic break with past activity—a recognition that the movement’s explicitly white supremacist goals could no longer be achieved within the existing political framework. When former Klansmen such as Robert Miles, Louis Beam, and Frazier Glenn Miller went to war with the U.S. government, they belied the simplistic slogan that “the cops and the Klan go hand in hand.” Today, when some leftists portray all rightist forces as working in concert, this is history that we need to understand.

Belew calls her subject the white power movement, and I’ll follow her usage in this review. She argues that “white power” is the best descriptor, and that “white nationalism” is a misnomer because “this movement did not seek to defend the American nation” (2). This is an odd misreading of “white nationalism,” which in my view succinctly captures the point that its proponents identify with a white nation rather than with the United States. “White nationalism” emphasizes the shift from the old-school, segregationist version of white supremacism to a new vision of an all-white society created through migration, mass expulsion, or genocide, while “white power” emphasizes the continuity between the two. “White power” has a slightly archaic feel; it evokes the 1960s American Nazi Party (which promoted the slogan in response to Black Power) but is rarely used by movement activists today.

The book’s title refers to Belew’s contention that the Vietnam War’s memory and legacy played a key role in unifying the white power movement and fueling its shift into paramilitarism, as leaders such as Beam urged fellow activists to “bring it on home” by waging war not on communists abroad, but on the United States government. Belew details how movement activists (many of them military veterans) used Vietnam War stories, symbols, and even equipment to help frame their new struggle as an extension of the old. She also suggests a larger connection between war and white supremacist activism across U.S. history, noting that since its founding after the Civil War, “Ku Klux Klan membership surges have aligned more neatly with the aftermath of war than with poverty, anti-immigration sentiment, or populism, to name a few common explanations” (20). Generalized this way it’s a weak argument, because many upsurges in racist activism didn’t follow wars, such as the wave of anti-black lynchings in the 1890s and 1900s or the explosive growth of fascist political groups in the 1930s. White supremacist violence has been too deeply rooted in this country at all levels for us to think of it as “overspills of state violence from wars [that] spread through the whole of American society” (21).

But when it comes to the Vietnam War influencing the white revolutionary underground, Belew is onto something. Because unlike all previous major wars, Vietnam represented a military defeat for the United States, and there is good reason to think that this collective patriotic trauma (coupled with civil rights legislation and other 1960s reforms) spurred many white supremacists to view the federal government not as weak, but as the enemy. The claim that Washington politicians betrayed the common soldiers by refusing to let them win echoed the “stabbed in the back” myth of why Germany lost World War I, which helped galvanize the German far right in the 1920s. In theoretical terms, the white power movement’s response to military defeat exemplifies Roger Griffin’s argument that fascist ideology centers on a myth of palingenesis (collective rebirth) and the need to rescue the nation or race from a profound crisis or decline.

Belew is rightly critical of those who portray attacks such as the Oklahoma City bombing or Dylann Roof’s massacre in a South Carolina church as isolated acts of violence rather than expressions of a movement. But her own account focuses so heavily on paramilitary activities that it doesn’t really describe the movement as a whole. She doesn’t mention Willis Carto’s sizeable propaganda operation centered on the Liberty Lobby and its newspaper Spotlight, says little about David Duke’s electoral activism, and discusses Tom Metzger’s White Aryan Resistance (WAR) only in relation to underground operations, passing over Metzger’s distinct strategy of organizing racist skinheads into a street-fighting force. There’s no discussion of the white power music scene, or activists’ wide range of views on religion or capitalism, or many of the other issues that white power groups addressed, such as ecology and AIDS. Belew offers valuable insights into the movement’s gender politics and the role that women played both as symbols for and unsung participants in the paramilitary network. But she doesn’t mention the ways that some movement women—such as the WAR-affiliated Aryan Women’s League or neonazi Molly Gill, publisher of The Rational Feminist newsletter—appropriated elements of feminist politics in the service of white supremacy. It’s perfectly valid and useful for Belew to write a book about the white power movement’s paramilitary wing with an emphasis on its underground activities, but misleading for her to claim that the book “captures the entire movement as it formed and changed over time” (15).

A more central problem concerns Belew’s treatment of leaderless resistance, the decentralized organizational form that Louis Beam and many others advocated to protect the white power underground against infiltration and repression. Belew presents leaderless resistance as a consensus approach within the movement and a seamless extension of the revolutionary strategy detailed in William Pierce’s influential novel The Turner Diaries. In reality, while leaderless resistance has played a key role in white power paramilitarism, it has also been fiercely debated within the movement. Pierce himself, who built the National Alliance into the biggest white power organization before his death in 2002, rejected leaderless resistance in favor of a top-down organizational model. In one 2000 article, Pierce declared that leaderless resistance was “simply an excuse for losers, cowards, and shirkers to do nothing except talk to each other” (quoted in Martin Durham, White Rage, p. 108).

Belew herself notes that Robert Mathews, who was a National Alliance member before founding the Order, “had a long-term plan for bringing the broader white power movement together under the command of the Order” (118). This plan was directly at odds with Beam’s argument in his “Leaderless Resistance” essay that a centrally directed cell system was “impossible” under U.S. conditions. Belew glosses over this disagreement by stating that leaderless resistance was intended to “obscure the coordination behind white power violence” (127)—rather than to eliminate the need for such coordination in the first place, as Beam himself argued.

My biggest criticism of Bring the War Home is that it portrays the militia movement as an outgrowth of the white power movement rather than a coalition where many different rightist currents interacted. There’s no question that white power groups such as Posse Comitatus heavily influenced the explosion of citizen militias in the 1990s, but so did Christian Reconstructionists, right-wing Mormons, John Birch Society conspiracists, gun rights activists, and Wise Use anti-environmentalists. When Belew writes that “the militia movement shared its leaders, soldiers, weapons, strategies, and language with the earlier white power mobilization” (191), she is only telling part of the story. She cites several early militia leaders who came out of white power groups, such as Militia of Montana founder John Trochmann, but doesn’t mention leaders who didn’t, such as Samuel Sherwood (who founded the Idaho-based U.S. Militia Association), Jon Roland (co-founder of the Texas Constitutional Militia), or Norm Olsen (who cofounded the Michigan Militia). And while some militia groups promoted blatant racism, others barred white supremacists from joining or even confronted white power groups directly. J.J. Johnson (who co-founded the Ohio Unorganized Militia) was himself African American and called the militias “the Civil Rights Movement of the '90s.” Belew might argue that all of this was secondary to the militias’ white power influences, but she can’t simply ignore the movement’s complexity on racial politics.

Many reviewers have praised Bring the War Home unreservedly as a powerful and carefully argued work of scholarship. One of the few dissenters is Mark Potok, formerly of the Southern Poverty Law Center, who calls it “a worthwhile book that makes many good points [but] is marred by a number of minor factual errors and a larger number of major, interpretive errors.” Potok criticizes Belew for ignoring factors other than war that have fueled white supremacist upsurges, and for relying on questionable sources in her account of the plot behind the Oklahoma City bombing. But in his concern to honor historical complexity and rigor, Potok dismisses what’s most important about Belew’s book—her recognition that in the early 1980s previously hostile white power factions coalesced as one movement and declared war on the state. Bring the War Home is by no means a definitive history of the modern white power movement, but it enriches our understanding of how it came into being.

Photo credit:

Oklahoma City, OK, 26 April 1995 -- Search and Rescue crews work to save those trapped beneath the debris, following the Oklahoma City bombing. FEMA News Photo, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Kathleen Belew’s 2018 book Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America traces the roots and development of a white supremacist revolutionary underground in the United States, covering the period from the late 1970s to the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. Belew, a history professor at the University of Chicago, has put a decade of research into this book, and she gives valuable accounts of Ku Klux Klan activism in Texas in the 1970s, the 1979 Greensboro massacre of leftists by a coalition of Nazis and Klansmen, U.S. white supremacists’ involvement with mercenary networks in Central America and elsewhere, and movement activists’ pioneering use of computer bulletin boards in the early 1980s. Bring the War Home provides a lot of detail that was new to me, and corrects at least one significant error in my own work. (In Insurgent Supremacists I described the prison-based Aryan Brotherhood as “primarily a criminal syndicate rather than a political organization,” but Belew argues persuasively that the organization was an important supporter of Aryan Nations in the 1980s, supplying both men and funds.)

What makes Belew’s book especially valuable is that it centers on the shift by many white supremacist groups from “vigilante violence,” which reinforced the existing state and related hegemonic structures, to “revolutionary violence,” which sought to overthrow the state (x, 106-107). The shift was spearheaded by the underground organization known as the Order, which formed in 1983 and carried out a series of killings, robberies, bombings, and other illegal activities over the next two years, but also involved several other paramilitary groups, such as the Carolina Knights of the Ku Klux Klan/White Patriot Party; Arizona Patriots; and Covenant, the Sword and the Arm of the Lord; as well as support and feeder organizations such as Aryan Nations. As Belew notes, the rise of these groups “has often been misunderstood as a simple resurgence of earlier Klan activity” (8), when in fact it represented a dramatic break with past activity—a recognition that the movement’s explicitly white supremacist goals could no longer be achieved within the existing political framework. When former Klansmen such as Robert Miles, Louis Beam, and Frazier Glenn Miller went to war with the U.S. government, they belied the simplistic slogan that “the cops and the Klan go hand in hand.” Today, when some leftists portray all rightist forces as working in concert, this is history that we need to understand.

Belew calls her subject the white power movement, and I’ll follow her usage in this review. She argues that “white power” is the best descriptor, and that “white nationalism” is a misnomer because “this movement did not seek to defend the American nation” (2). This is an odd misreading of “white nationalism,” which in my view succinctly captures the point that its proponents identify with a white nation rather than with the United States. “White nationalism” emphasizes the shift from the old-school, segregationist version of white supremacism to a new vision of an all-white society created through migration, mass expulsion, or genocide, while “white power” emphasizes the continuity between the two. “White power” has a slightly archaic feel; it evokes the 1960s American Nazi Party (which promoted the slogan in response to Black Power) but is rarely used by movement activists today.

The book’s title refers to Belew’s contention that the Vietnam War’s memory and legacy played a key role in unifying the white power movement and fueling its shift into paramilitarism, as leaders such as Beam urged fellow activists to “bring it on home” by waging war not on communists abroad, but on the United States government. Belew details how movement activists (many of them military veterans) used Vietnam War stories, symbols, and even equipment to help frame their new struggle as an extension of the old. She also suggests a larger connection between war and white supremacist activism across U.S. history, noting that since its founding after the Civil War, “Ku Klux Klan membership surges have aligned more neatly with the aftermath of war than with poverty, anti-immigration sentiment, or populism, to name a few common explanations” (20). Generalized this way it’s a weak argument, because many upsurges in racist activism didn’t follow wars, such as the wave of anti-black lynchings in the 1890s and 1900s or the explosive growth of fascist political groups in the 1930s. White supremacist violence has been too deeply rooted in this country at all levels for us to think of it as “overspills of state violence from wars [that] spread through the whole of American society” (21).

But when it comes to the Vietnam War influencing the white revolutionary underground, Belew is onto something. Because unlike all previous major wars, Vietnam represented a military defeat for the United States, and there is good reason to think that this collective patriotic trauma (coupled with civil rights legislation and other 1960s reforms) spurred many white supremacists to view the federal government not as weak, but as the enemy. The claim that Washington politicians betrayed the common soldiers by refusing to let them win echoed the “stabbed in the back” myth of why Germany lost World War I, which helped galvanize the German far right in the 1920s. In theoretical terms, the white power movement’s response to military defeat exemplifies Roger Griffin’s argument that fascist ideology centers on a myth of palingenesis (collective rebirth) and the need to rescue the nation or race from a profound crisis or decline.

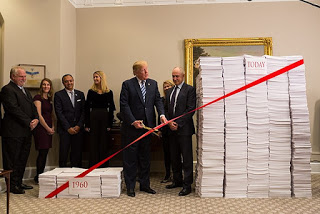

|

| Oklahoma City bombing, April 1995 |

A more central problem concerns Belew’s treatment of leaderless resistance, the decentralized organizational form that Louis Beam and many others advocated to protect the white power underground against infiltration and repression. Belew presents leaderless resistance as a consensus approach within the movement and a seamless extension of the revolutionary strategy detailed in William Pierce’s influential novel The Turner Diaries. In reality, while leaderless resistance has played a key role in white power paramilitarism, it has also been fiercely debated within the movement. Pierce himself, who built the National Alliance into the biggest white power organization before his death in 2002, rejected leaderless resistance in favor of a top-down organizational model. In one 2000 article, Pierce declared that leaderless resistance was “simply an excuse for losers, cowards, and shirkers to do nothing except talk to each other” (quoted in Martin Durham, White Rage, p. 108).

Belew herself notes that Robert Mathews, who was a National Alliance member before founding the Order, “had a long-term plan for bringing the broader white power movement together under the command of the Order” (118). This plan was directly at odds with Beam’s argument in his “Leaderless Resistance” essay that a centrally directed cell system was “impossible” under U.S. conditions. Belew glosses over this disagreement by stating that leaderless resistance was intended to “obscure the coordination behind white power violence” (127)—rather than to eliminate the need for such coordination in the first place, as Beam himself argued.

My biggest criticism of Bring the War Home is that it portrays the militia movement as an outgrowth of the white power movement rather than a coalition where many different rightist currents interacted. There’s no question that white power groups such as Posse Comitatus heavily influenced the explosion of citizen militias in the 1990s, but so did Christian Reconstructionists, right-wing Mormons, John Birch Society conspiracists, gun rights activists, and Wise Use anti-environmentalists. When Belew writes that “the militia movement shared its leaders, soldiers, weapons, strategies, and language with the earlier white power mobilization” (191), she is only telling part of the story. She cites several early militia leaders who came out of white power groups, such as Militia of Montana founder John Trochmann, but doesn’t mention leaders who didn’t, such as Samuel Sherwood (who founded the Idaho-based U.S. Militia Association), Jon Roland (co-founder of the Texas Constitutional Militia), or Norm Olsen (who cofounded the Michigan Militia). And while some militia groups promoted blatant racism, others barred white supremacists from joining or even confronted white power groups directly. J.J. Johnson (who co-founded the Ohio Unorganized Militia) was himself African American and called the militias “the Civil Rights Movement of the '90s.” Belew might argue that all of this was secondary to the militias’ white power influences, but she can’t simply ignore the movement’s complexity on racial politics.

Many reviewers have praised Bring the War Home unreservedly as a powerful and carefully argued work of scholarship. One of the few dissenters is Mark Potok, formerly of the Southern Poverty Law Center, who calls it “a worthwhile book that makes many good points [but] is marred by a number of minor factual errors and a larger number of major, interpretive errors.” Potok criticizes Belew for ignoring factors other than war that have fueled white supremacist upsurges, and for relying on questionable sources in her account of the plot behind the Oklahoma City bombing. But in his concern to honor historical complexity and rigor, Potok dismisses what’s most important about Belew’s book—her recognition that in the early 1980s previously hostile white power factions coalesced as one movement and declared war on the state. Bring the War Home is by no means a definitive history of the modern white power movement, but it enriches our understanding of how it came into being.

Photo credit:

Oklahoma City, OK, 26 April 1995 -- Search and Rescue crews work to save those trapped beneath the debris, following the Oklahoma City bombing. FEMA News Photo, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.