Conquering Mount Everest: High hopes and broken dreams

Updated

This year's Mount Everest "summit window" was brief and it was deadly. By the time the window closed for the final time on May 29, 12 people had died, making 2019 one of the deadliest years on record.

As the surviving climbers and their teams packed up and made their way home, they left behind another tragic chapter in Himalayan mountaineering history and more bodies on the mountain graveyard.

Ever since Sir Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay became the first people to summit Everest in 1953, a legion of mountaineers and adventurers have been inspired to follow their lead up the 8,850m peak straddling the border of Nepal and Tibet.

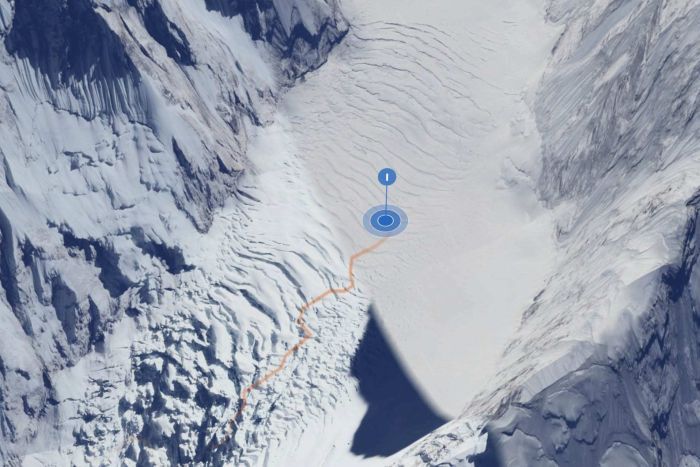

The journey to the summit along the more popular South Col route begins at Base Camp, 3,540m below the summit on the Nepalese side of the mountain.

At 5,400m above sea level, South Base Camp lies at the foot of the Khumbu Glacier.

Here oxygen levels are only 52 per cent of those at sea level. During climbing season, the area is transformed into a sprawling encampment of tents where climbers acclimatise to the rarified air and wait for the weather windows to open.

Photo:

Everest South Base Camp in May, 2019. The yellow dots are tents. (Suppliled: Facebook/Lakpa Norbu Sherpa)

Photo:

Everest South Base Camp in May, 2019. The yellow dots are tents. (Suppliled: Facebook/Lakpa Norbu Sherpa)

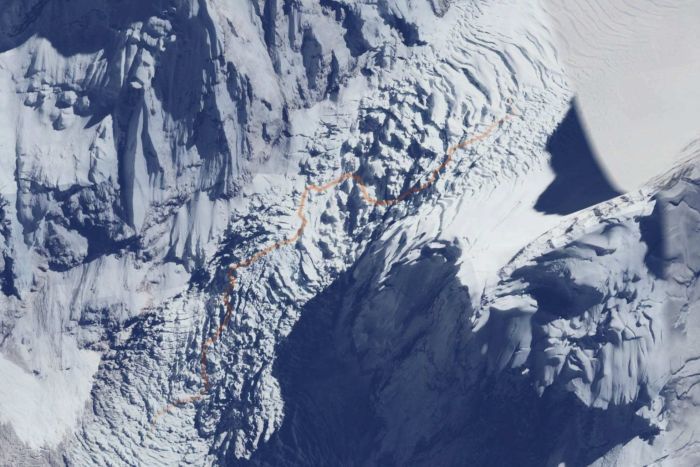

Leaving Base Camp, climbers and their guides proceed up the glacier through a zone known as the Khumbu Icefall. This is one of the most treacherous stretches of the lower slopes.

Crevasses, collapsing ice pinnacles and avalanches are just some of the potentially fatal obstacles.

The 2.6km trek over the icefall can take between three and eight hours, depending on conditions and the state of a mountaineer's acclimatisation.

Also known as the Valley of Silence, Camp 1 lies at an altitude of 6,000m, where oxygen levels drop below 50 per cent.

The big danger on the approach is the presence of many crevasses. Climbers must use ladders and fixed ropes to make their way across the vast snowfield.

The snow-covered topography around the camp amplifies solar radiation and daytime temperatures can hit 35 degrees Celsius.

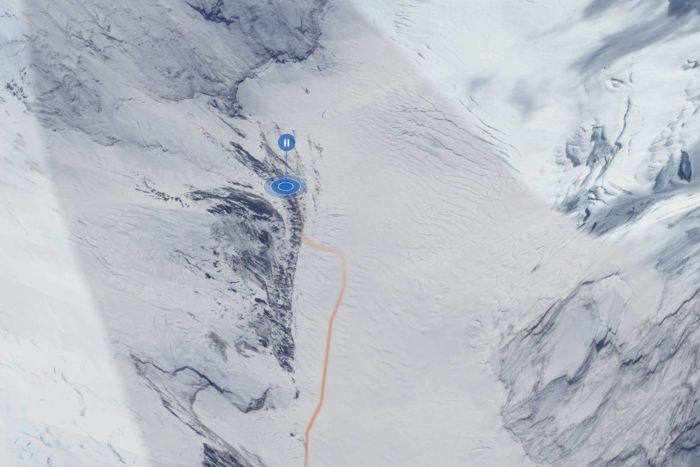

Camp 2 is situated a further 2.8km away, at the foot of the Lhotse Face — an imposing kilometre-high wall of glacial ice.

At an altitude of 6,400m, this is usually the last place where climbers can get a hot, prepared meal.

The area is littered with gear abandoned by earlier expeditions lightening their load before the return to Base Camp.

Perched on top of the Lhotse Face, Camp 3 lies around the 7,200m mark and level surfaces are at a premium.

The 2.6km route up and over the Lhotse ice wall can take anywhere between four and eight hours.

At this altitude, oxygen levels in the atmosphere drop to about 40 per cent of those experienced at sea level and for many, this is the last chance to breathe unassisted.

Camp 4 is the final stop on the way to the summit and lies just a few meters shy of the 8,000m elevation mark.

From here, climbers must conserve their energy for the long day ahead and wait for the right conditions to launch a final assault on the summit.

At an altitude of almost 8,000m-plus, the air is so thin and the weather so fickle that climbers have only a very limited survival time.

This is known as the Death Zone.

It was from here that the famous image of this year's summit queue was taken, showing the long snaking line of climbers making their final vertiginous surge towards the top.

The camera looks up towards a rocky outcrop known as the Hillary Step, which is about 60m below the summit and, historically, was the final major obstacle before the summit.

The 2015 earthquake dislodged the boulder and as a result, the step is now much less of an impediment.

This is the summit of Mount Everest. At an elevation of 8,850m, you are literally on top of the world.

Mountaineers usually stay no longer than 30 minutes — enough time to catch their breath, take their photos and prepare themselves for the long and dangerous descent.

Google Earth: Digital Globe

Of the 12 fatalities this season, all but two perished on the Nepalese side. Of the others, two are missing, presumed dead. And all bar one of the victims were foreign climbers.

The bid for the summit is often assumed to be the most hazardous part of the expedition to the top of the world.

For foreigners, however, the descent is the most treacherous element of the journey.

Half of foreigner deaths (51 per cent) occur on the descent from the summit, when climbers — spent from the push to the top — are more susceptible to falling or losing concentration and making mistakes.

Others find that their bodies succumbing to altitude sickness or other illnesses, no longer steeled by the dream of conquering the summit.

These figures come from the Himalayan Database, which has tracked every expedition since 1905 to more than 450 peaks in the Nepal Himalayas, plus expeditions to both sides of border peaks, including Everest. The latest figures are from 2018.

The database points to significant differences in where, why and how foreigners and Sherpas die — a stark reminder that these two groups may trace the same route, but do not face the same perils.

Much of this boils down to the critical work of Sherpas, who press ahead, forging the track, hauling loads of gear and setting up ladders, ropes and other safety mechanisms before going back to assist their clients.

Sherpas are also more exposed to the risks because many make multiple treks. On Everest, each Sherpa makes 3.5 ascents on average, while foreign climbers average 1.5 ascents.

This year, Kami Rita Sherpa reached the Everest peak on May 21 for a record 24th time. And that was just a week after his 23rd successful summit.

All this means foreigners are largely spared the most dangerous hazards of the lower slopes, such as avalanches. On the other hand, they cannot be completely shielded from Everest's thin mountain air or sheer physical exhaustion.

These patterns are clearly played out in the data. Nearly two-thirds of Sherpa deaths (63 per cent) occur during route preparation. Sherpas are nearly 4.5 times more likely than foreigners to die from external hazards, such as avalanches, collapsing ice towers and crevasse falls.

They are half as likely to die from falls — the most common cause of death for foreigners — or physical ailments such as exhaustion, acute mountain sickness or other illnesses.

The deadliest altitudes for foreigners are close to the summit, with more than 56 per cent of foreigner deaths at altitudes of 8,000m or higher and 77 per cent at 7,000m or higher.

For Sherpas, on the other hand, the deadliest altitudes are between 5,300m and 5,800m, which includes the trek through the Khumbu Icefall to Camp 1. Nearly half of Sherpa deaths since 1921 were in this zone.

A further 20 per cent occurred between 6,400m and 6,900m, between Camp 2 and Camp 3, where climbers must scale the Lhotse Face glacial ice wall.

Yet despite all the publicity around the annual Everest death toll, it is not the most dangerous peak for mountaineers.

The fatality rate on Mount Everest stands at 1.15 per cent — well below neighbouring Himalayan giants such as Annapurna I, with a death rate of 3.9 per cent, or Dhaulagiri I, with a rate of 2.99 per cent.

Including this year's confirmed deaths, 187 foreigners and 120 Sherpas have perished on Everest since records began in 1921.

With 12 deaths this spring season, 2019 is already the fourth-deadliest year on record and the second-deadliest for foreign climbers, measured by the number of fatalities.

However, the rate of death — which takes into account the ballooning number of climbers — has been falling over the long term. By this measure, 2019 is set to be one of the safest years on record.

But whether this downward trend can be sustained in the face of the booming number of climbers remains to be seen.

Overcrowding, along with inexperience, has been blamed for this year's death toll, with "traffic jams" at the summit forcing climbers to wait in line, their precious stores of oxygen ebbing lower with each passing minute.

Numerous tour operators and Everest-watchers have expressed concern over the number of novice mountaineers taking on the challenge, saying many possess neither the skills nor experience to tackle such a treacherous feat.

In some ways, Everest tour operators have become victims of their own success. A solid safety record and skyrocketing rates of summiting have greatly heightened Everest's allure, especially among bucket listers.

Between 1921 and 2018, more than half of the 20,609 ascents failed to reach the summit.

However, success rates greatly improved throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, soaring from less than 10 per cent in the 1980s to 25 per cent in the 1990s and 47 per cent in the 2000s.

In 2018 a record 78 per cent of climbs reached the summit.

US adventurer Melissa Arnot has summited Everest six times and now spends every climbing season guiding people up the mountain.

She has watched unscrupulous expedition companies move into the market to service cashed-up but inexperienced climbers.

"There's always going to be an opportunity for somebody to come in and take advantage of a hole in the market," she told ABC News. "Sometimes it's an operator that just shows up for one season and then they're gone."

In the century since the first recorded attempt to scale Everest in 1921, roughly 12,500 people have attempted the same feat — many multiple times.

And as the number of foreigners that has increased, so, too, has the number of Sherpas, exacerbating problems with overcrowding.

Sherpas now make up close to one in two climbers, compared with roughly one in 10 during the 1970s and 1980s.

Safety is one driving factor — the Nepalese government now requires all clients to have guides accompany them to the summit.

Another is comfort, with camps becoming more luxurious to meet the expectations of less experienced clients who are sometimes more reluctant to tough it out, particularly when forking out hefty fees that can be north of $US100,000 per person.

But the data reveals another factor behind the "traffic jam" at the top of the world: a shrinking summit window.

Most of the year Everest is susceptible to being buffeted by gale-force winds associated with the polar front jet stream in the summer and heavy snows in the winter.

But for a brief period in May (and less so during September), the polar front jet stream moves to the north. Winds that can get as strong as 185 km/h drop below 40 km/h and the average winter temperature peak of -36 degrees Celsius rises to a more bearable -25 degrees.

Across the 1980s and 1990s, this summit window was much wider, with over 70 per cent of summits dates spread across more than three weeks in May (5 - 29 May).

By contrast, a staggering 90 per cent of summit dates since 2000 were concentrated within a 13-day window between May 15 and May 27.

Not only that — swelling numbers of climbers combined with soaring "success" rates mean that roughly seven times as many people have conquered the summit since 2000 as in the 1980s and 1990s combined.

Roughly 7,200 climbers have reached the peak in the past 20 years, compared to just over 1,000 in the previous 20 years, according to the Himalayan Database.

Canadian adventure filmmaker Elia Saikaly has now climbed Everest three times.

He said the slow shuffle to the summit on May 26 was unlike anything he'd ever experienced — including the disastrous 2015 season when an avalanche triggered by an earthquake killed 11 Sherpas and three foreigners, according to the database.

"It was the sheer number of bodies we had to pass. On the way to Camp 4, there were two deceased climbers attached to the side of the trail waiting for evacuation," he told ABC News.

"Within 20 minutes, we passed another lifeless body that was being brought down. Three hours into it, the fifth body. Just beneath the Hillary Step, the sixth.

"You have got to ask yourself, what is going wrong here?

"Every single person that was attached to the summit had to step over that human being. It's devastating."

Notes about this story

- "Foreigners" has been used to describe the clients of tour operators. It includes a small number of clients from the Himalayan region.

- "Sherpas" has been used to describe climbers hired to assist expeditions. It includes a small number of hired climbers who are not ethnically Sherpa.

- The Himalayan Database includes information for hired climbers (i.e. "Sherpas") involved in significant events such as a summit success, death, accident or rescue. The exclusion of Sherpas who assisted expeditions but were not involved in significant events may affect figures on the number of ascents and ratio of Sherpas to foreigners. However the authors of the Himalayan database have confirmed to ABC News that the trends described in this story are accurate.

- Data on Everest deaths in 2019 was compiled by ABC News and added to Himalayan Database figures where relevant. The 2019 data includes Chris Daly, who died in April while descending from Base Camp.

Credits

- Reporting: Inga Ting, Stephen Hutcheon and Siobhan Heanue

- Design: Alex Palmer

- Development: Nathanael Scott

Topics: disasters-and-accidents, lifestyle-and-leisure, travel-and-tourism, travel-health-and-safety, nepal, china

First posted