buggery.org

Better than a poke in the eye with a wet fish

On the PBAC rejection of Truvada as PrEP

A couple of (lengthy) comments on the #PrEP decision today:

1. Don’t blame PBAC

We’re all angry and disappointed by this decision, but it’s important we’re clear where our anger is directed. A fair few of the comments I’ve seen in the last couple of hours have expressed anger at PBAC for making the decision the way they did. But it’s Gilead, not PBAC, we should be angry with.

PBAC operates to a very narrowly-defined mandate: its one and only task is to determine whether drug listing are cost-effective. For a novel intervention like PrEP, that means comparing the cost of what the drug company is offering with the cost of doing nothing. Simply put, if the benefit is greater than the cost, the drug gets recommended; in this case, the cost outweighed the benefit.

PBAC also only considers the application made by the drug company. To protect its profits, Gilead chose to make their application based on only approving PrEP for people at very high risk of HIV (specifically, those with a greater than 3% risk of infection in 12 months), and at a high cost (we don’t know the exact cost they quoted, but we can assume it’s not much different from the current PBS price of $750/month). PBAC quite rightly questioned how practical or feasible it would be for doctors to determine which of their patients had a greater than 3% annual risk of HIV infection, and made it crystal clear they would prefer to see an application that would make PrEP available to everyone who could benefit, at an appropriately reduced price.

Let’s be clear: those pills cost a few sets each to make, and Gilead had a choice about how to structure its PBAC application. It chose to take a path that would give it the best return while denying PrEP to the majority of people who could benefit from it. That proposal would have seen hundreds of needless HIV infections every year, because its not just people at highest risk who get HIV.

2. The language of the decision

A couple of phrases in the PBAC decision seem to have inflamed people’s passions. I think some clarity is needed.

“attempts to restrict the eligible population by quantifying an individual’s future risk of HIV infection based on self-reported future behaviour, and limiting access to those with a predicted annual risk of infection of 3% or higher, may not be feasible or acceptable to clinicians and consumers.”

This, I think, is unproblematic. PBAC is saying that Gilead’s proposal to limit the use of PrEP to people at high risk “may not be feasible or acceptable.” It would require clinicians to make an assessment of the annual risk of HIV infection based on the patient’s self-reported behaviour. This is likely to be both inexact and practically impossible – if you were a doctor, could you make this judgement in a meaningful way? As PBAC goes on to say, far better to make the drug more widely available and let doctors and patients decided together if they feel the benefit outweighs the risk for that person.

“The PBAC noted that the efficacy of Truvada was highly dependent on adherence, and that it is not clear if subjects at high risk of contracting HIV due to self-reported low adherence to safer sex practices would also have lower adherence to medication.”

This sentence has a lot of people riled up, who have characterised it as saying ‘if gay men can’t be bothered using condoms, why would they bother taking PrEP?’ I think the statement refers back to the earlier questions about the viability of limiting PrEP to people at high risk. Many people at highest risk of HIV have difficulty with safe sex for quite legitimate structural reasons – homelessness, poor mental health, substance abuse issues, low literacy, etc. Limiting PrEP to that group could artificially increase the proportion of PrEP users who have adherence problems (due to the same structural factors) and consequently, this may not be the most efficient way to use the drug. Again, if the price were lower, it could be prescribed based on patient choice rather than arbitrary criteria, and we know most medicines work best when used that way.

Today’s decision has been a huge disappointment, but it’s not the end of the road. It often takes several application to PBAC before a new drug or indication is approved, and Gilead should be encouraged to resubmit. But we as a community have to hold the company to account – its next application must be structured around delivering the best public health outcomes, not the highest profits. Gilead stands to make a lot of money out of PrEP, even if they reduce the price radically, which is what they have to do before we get the outcome we want and need. The gay community has been doing its part to combat this disease for 30+ years, while Gilead and other drug companies have profited massively from it. It’s time for them to come to the table and do their part to prevent, not just profit from, HIV infections.

In the meantime, unfortunately there will be dozens or hundreds of needless HIV infections. We need to do what we can to minimise those, and to care for the unlucky ones who slip through the cracks.

Pills cost pennies, Gilead’s greed is ruining lives.

Australia’s HIV transmission rate falls

New data out of the Kirby Institute shows that the rate of HIV transmission in Australia has fallen, returning to a downward trend that has been the norm for more than a decade. So why are the papers saying that HIV infections are ‘at an 20-year high‘?

As I have been arguing for several years (see this post from 2013 and this one from 2010) the use of raw diagnoses as the only measure of progress against HIV in Australia fails to take account of the reality that there are more people living with HIV every year. With a greater HIV-positive population, in any HIV prevention scenario a greater number of new diagnoses can be expected. Because this is the case, simply looking at the number of new diagnoses tends to mask the considerable success we have had in combating HIV.

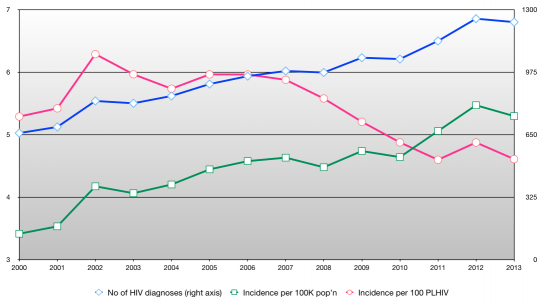

Here’s a graph that shows (in pink) the ‘HIV transmission rate’ (the number of new infections recorded per 100 people living with HIV) in Australia over the last 13 years:

The blue line shows the official HIV stats, and there’s no doubt they have trended upwards over the period. That’s nobody’s idea of good news, least of all mine. We want to turn that line around (and I think we will soon).

The pink line is my estimate of the HIV transmission rate. As you can see, it has actually fallen in nine out of the last 11 years and, despite a rise last year, it looks to be trending downwards. That is a good sign that, despite the rising population of PLHIV, the percentage of people who pass HIV on has been falling. That is a marker of success that is ignored by the official reports.

The use of the transmission rate as an alternative to the raw numbers isn’t just my idea: the US National HIV/AIDS Strategy uses it. The CDC uses it. Peer-reviewed epidemiological studies use it.

I am not suggesting we should ditch the reporting of the raw numbers – they are a useful and important measure. Governments and health economists care, as they should, about the numbers of people who will need medical care and support into the future. But they are less helpful when measuring the success of HIV prevention campaigns. A rise in infections doesn’t mean that prevention is failing unless the rise is greater than that which can be attributed to the increased PLHIV population. In fact, as the graph above shows, in most recent years the rise in infections is below that natural increase and that means we have had some measure of success – not that you’d know it from reading media reports or Kirby Institute press releases.

Stories headlined ‘HIV infections at a 20-year high’ suggest that, 20 years ago, things were better than they are now. They weren’t: people were dying in droves. The rate of HIV infections in 1994 was unnaturally low because a large proportion of PLHIV were seriously ill and dying. Suggesting that we have an alarming rise in new infections 20 years later, when we have twice as many people living with HIV and most of them are leading healthy, productive (and sexually active) lives is blinkered pessimism.

Disclaimer: as with my previous posts on this topic, I have to point out that I am neither an epidemiologist nor a statistician, and while my estimate is based on published data from the Kirby Institute, I don’t have access to the detailed data on which it is based.

It’s not true, is it?

The International AIDS Conference is starting in Melbourne in a few days. I’m in a convenience store , wearing this T-shirt that says ‘HIV Positive’. There’s music playing, in a language I don’t understand.

“I like the music,” I tell the clerk.

“You probably can’t understand what she’s saying. It’s in Persian – Farsi.”

I hand over my purchases.

“It’s not true, is it?” he says, pointing to my T-shirt as I pay.

“Yes, it is true.” He makes a screwed-up smile, unsure whether I’m pulling his leg. A moment of silence. “Really?”

I tell him about the AIDS conference, and something about the importance of positive people being visible. Another moment of silence.

“You know, when I tell people I’m from Iran, they make assumptions about me, too. It’s good to meet you, my friend.” He shakes my hand and I leave.

A blunt instrument

The following article about HIV criminalisation, by David Mejia Canales and me, was originally published on the Law Institute of Victoria Young Lawyers’ Blog last week. (Yes I have been published on a ‘young lawyers’ blog – I am aware that is amusing on several levels).

The International AIDS Conference will be held in Melbourne in July. The conference, one of the largest in the world, attracts tens of thousands of activists, politicians, scientists, doctors and a diverse group of community members affected by HIV.

With the world’s eyes on Melbourne during the conference, it’s timely that we revisit our criminal laws with regards to HIV transmission.

Did you know that s 19A of the Victorian Crimes Act is the only law in any Australian jurisdiction that specifically criminalises the transmission of HIV? The maximum penalty under the section is 25 years’ imprisonment – equivalent to armed robbery or aggravated crimes of violence.

Section 19A was introduced in 1993 to placate community fears of robberies with HIV-infected blood-filled syringes, but no HIV-positive person has ever been convicted of such a crime. Instead, the law has only ever been used for allegations of sexual transmission.

So is s 19A a good law? It’s only produced one conviction in 20 years (and this was for attempt); it was intended to be used to punish robbers armed with HIV laden syringes but has only been used to lay charges against people who have allegedly transmitted HIV through sex.

This is not to say that intentional transmission of a serious disease like HIV should not be a crime – there’s no doubt it should. But other sections of the Crimes Act are capable of being used should such a scenario occur. Not only that, we have public health processes that can be triggered when HIV transmission occurs, and which are focused on achieving positive behaviour change rather than punishing past wrongs.

In theory, s 19A was intended to protect the public, but what happens in practice is it acts as a disincentive to knowing your HIV status while reinforcing perceptions that people living with HIV are dangerous or malicious. This does no one any good.

Laws don’t exist in a vacuum. You probably didn’t learn about s 19A at law school, and you definitely didn’t learn about the incredible social baggage a discussion about HIV and transmission brings.

Here are four things you can do today to know more about the fascinating junction of law, human rights and HIV:

- Register for Beyond Blame: Challenging HIV Criminalisation, an International AIDS Conference affiliated event about the criminalisation of HIV, not just in Victoria but around the world. The event is free to attend but you must register. Keynote speaker: Hon Michael Kirby. Registrations here: http://beyondblame.eventbrite.com.au

- Contact organisations like Living Positive Victoria or the Victorian AIDS Council, they can organise speakers or information sessions for you or your organisation to understand HIV and the human rights issues surrounding it. www.vicaids.asn.au and www.livingpositivevictoria.org.au

- Take part in the hundreds of events during the International AIDS Conference, for more details: www.aids2014.org

- Consider volunteering or donating to the HIV/AIDS Legal Centre, a community legal centre assisting HIV positive Victorians. For details: http://www.vac.org.au/plc-legal-assistance

What do you think? Is it possible to have a constructive discussion about HIV and decriminalisation of HIV without the fear and hysteria that usually comes with discussions about HIV?

About the authors: David Mejia-Canales is a lawyer and Vice President of the Victorian AIDS Council. Paul Kidd is an HIV activist, current law student at La Trobe University and the Chair of the HIV Legal Working Group at Living Positive Victoria.