Lake Eyre in Central Australia is filling in a way not seen for 45 years

Updated

Across Australia's central deserts, floodwaters are filling Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre, but with the water comes a message: let the rivers run.

Photo:

Blue waters meet the salty sand of Lake Eyre in northern South Australia. Photo taken April 17, 2019. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Photo:

Blue waters meet the salty sand of Lake Eyre in northern South Australia. Photo taken April 17, 2019. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

In the vast desert of inland Australia, nothing stands in the way of the water.

Photo:

Salt and light produce art on Lake Eyre North in South Australia. Photo taken April 17, 2019. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Photo:

Salt and light produce art on Lake Eyre North in South Australia. Photo taken April 17, 2019. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Often destructive, but always regenerative, these floodwaters from Australia's north flow freely through the central deserts, unleashing nature's artistic genius along the way.

The Lake Eyre Basin is one of the largest and most pristine desert river systems on the planet, supporting 60,000 people and a wealth of wildlife.

It's a rarity in a world that has harnessed, tapped, pumped and dammed its rivers, sometimes, to death.

Residents say they've learnt to go with the flow even though, mostly, there is none.

When the water does come, you celebrate the moment, but you "don't get greedy".

This year, the water arrived in a way not seen for 45 years and, as mining exploration has locals worried, they are using the occasion to sound a warning.

This is what it looks like when a river is left to run.

Photo:

The blue flood waters on Lake Eyre meet the dry sands in northern South Australia. Photo taken April 17, 2019. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Photo:

The blue flood waters on Lake Eyre meet the dry sands in northern South Australia. Photo taken April 17, 2019. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

When the earth is a blank canvas and the water determines its own shape.

Photo:

Blue salt on Lake Eyre sand in northern South Australia makes a dot pattern. Photo taken April 17, 2019. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Photo:

Blue salt on Lake Eyre sand in northern South Australia makes a dot pattern. Photo taken April 17, 2019. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

It moves free of any human intervention.

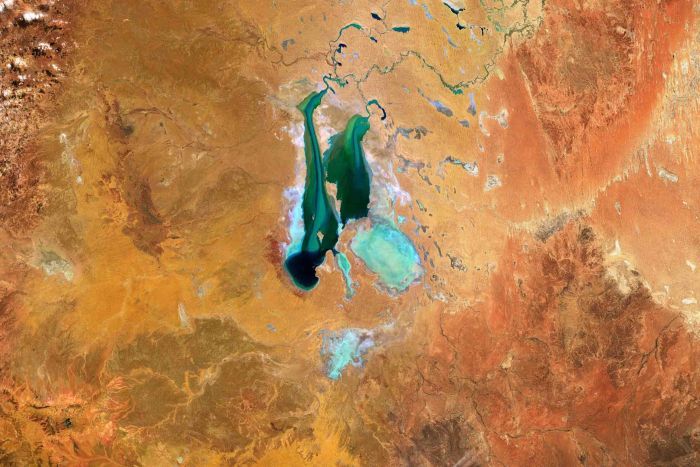

The Lake Eyre Basin covers one-sixth of Australia across four states and territories. It's fed by three major systems — the Georgina and Diamantina rivers and Cooper Creek.

Photo:

The Lake Eyre Basin covers large parts of four Australian states and territories. (ABC News: Alex Palmer)

Photo:

The Lake Eyre Basin covers large parts of four Australian states and territories. (ABC News: Alex Palmer)

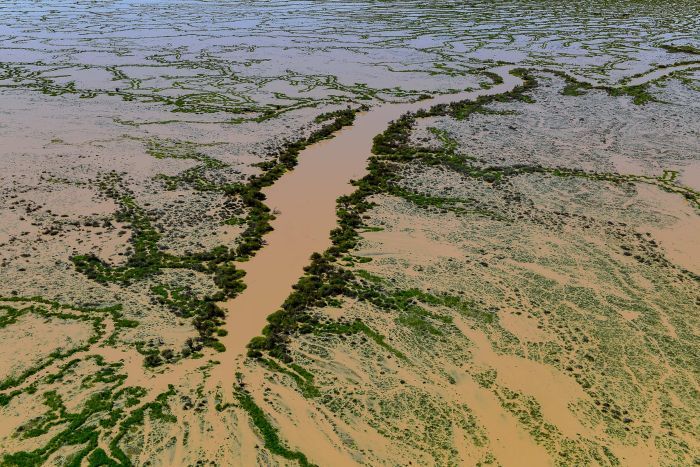

Floodwaters from the north drain towards Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre — the country's lowest point — spilling over riverbanks and across the floodplains, filling waterholes and wetlands, and carving new arteries across the landscape — giving the Channel Country its name.

Most of the rain which falls in the north never finishes the 1,000-kilometre journey to the lake, making the event of its filling so incredible.

The land is a sponge. Evaporation across the basin is 20 times the average annual rainfall.

Photo:

A satellite image using a different frequency shows the extent of the moisture in Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre by April 18. (Supplied: SentinelHub)

Photo:

A satellite image using a different frequency shows the extent of the moisture in Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre by April 18. (Supplied: SentinelHub)

Historically, the water's journey south has taken anywhere from three to 10 months, but this year, it was much faster, arriving in two.

The sheer volume of water created by the torrential downpour in Queensland at the end of January meant water started arriving at the lake in late March.

What the water brings

The floodwaters devastated communities upstream, killing an estimated 500,000 cattle and inundating homes, but down here the water is a force for good.

With the water comes an explosion of insects, fish and birdlife, as they take advantage of nature's small window of opportunity to breed.

Fish, confined in dry times to a few permanent waterholes, ride the floods across the basin, while millions of water birds fly in from the coast.

The Diamantina River at Birdsville is churning with life, as thousands of small fish try to haul themselves upstream.

"This is nothing," says Aboriginal elder Don Rowlands, who is the chief ranger for the Munga Thirri National Park in the Simpson Desert.

"At times, the whole river is boiling with fish."

This is what a flood brings to Birdsville and another is on its way, down Eyre Creek from Bedourie, courtesy of Cyclone Trevor.

It's "pretty unusual" to have two floods in a row, Don says, "and that's why we're pretty lucky with this river and why it should stay the way it is: no interference up-stream, like dams or extraction of water, or anything at all — because we would miss this flow … big time," he says.

Photo:

Indigenous ranger Don Rowlands with floodwaters in Birdsville, Queensland. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Photo:

Indigenous ranger Don Rowlands with floodwaters in Birdsville, Queensland. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Indigenous Australians, more than any others, know how to live with the cycles of this harsh land. They've been doing it for thousands of years.

Traditional owners, like most who live within the basin, are fiercely protective of its natural systems.

Unlike Australia's Murray-Darling, this system has no major irrigation, diversions or flood-plain developments.

Locals fought off an attempt in 1995 to introduce large-scale irrigated cotton farming on the basin's Cooper Creek, and they fear the system may again be under threat.

In 2014, Queensland's Liberal National Party changed the laws protecting the rivers and floodplains in the Channel Country, which environmentalists say, potentially opens them up to shale gas mining, or fracking.

In opposition, Labor promised to protect these environmentally sensitive areas, but now in government in Queensland, it continues to release land for oil and gas exploration, according to Fiona Maxwell from the Pew Charitable Trusts.

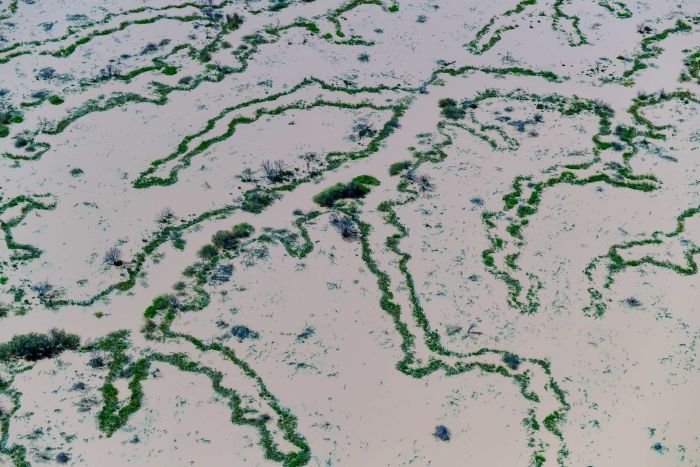

Photo:

New grasses are seen growing in flood waters on Clifton Hills Station in far-north South Australia. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Photo:

New grasses are seen growing in flood waters on Clifton Hills Station in far-north South Australia. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Tens of thousands of square kilometres of the basin are now approved for oil and gas exploration, she says.

Don says no one can afford to be complacent.

"Absolutely not, absolutely not … You need these rivers to run free — run unregulated, and the way they are," he says.

"They are a very important resource for everyone."

Photo:

The red colour of Lake Eyre Basin is seen from a plane in northern South Australia. Photo taken April 17, 2019. (ABC News:Brendan Esposito)

Photo:

The red colour of Lake Eyre Basin is seen from a plane in northern South Australia. Photo taken April 17, 2019. (ABC News:Brendan Esposito)

In a matter of two weeks, the red earth can transform.

Photo:

Green new growth is seen on land around Lake Eyre in northern South Australia. Photo taken April 18, 2019. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Photo:

Green new growth is seen on land around Lake Eyre in northern South Australia. Photo taken April 18, 2019. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Plains can glow green.

'Just add water'

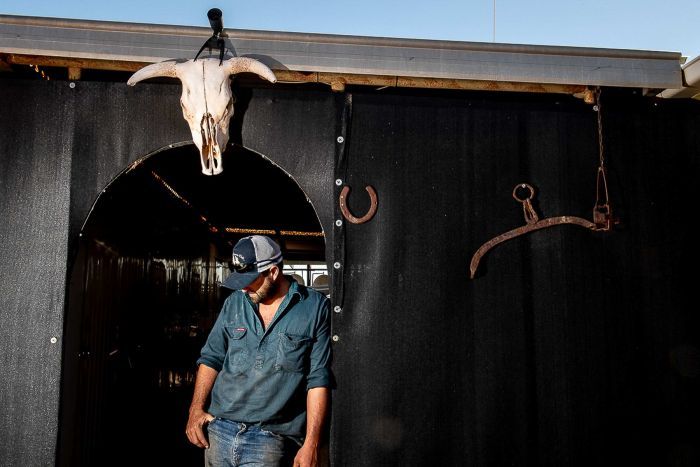

For fourth-generation grazier Craig Oldfield, this flood is a "game changer".

"It's just like magic, just add water and it's green grass," he says.

Brothers Craig and Chris Oldfield have seen the extremes this place can serve up.

On the Oldfield station, Cowarie, they've been in and out of drought since 2005.

Beneath the property is the huge underground reserve of the Great Artesian Basin, but they're allowed to draw bore water only for household use and for their cattle to drink.

Irrigating pasture is just a dream.

Photo:

Water snakes through the dry earth around Lake Eyre in South Australia. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Photo:

Water snakes through the dry earth around Lake Eyre in South Australia. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Craig says the idea of harvesting water during floods to survive the dry times is enticing, but everyone and everything depends on the water running its course.

"To be honest, the natural cycle of the system is probably enough for me at this point," he said.

"A bit more often would be nice, but we make do with what we've got."

Photo:

Just metres away, another Queensland bluebush is brought to life by floodwaters. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Photo:

Just metres away, another Queensland bluebush is brought to life by floodwaters. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Photo:

Craig Oldfield (pictured right) and his brother Chris Oldfield under a Coolabah tree. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Photo:

Craig Oldfield (pictured right) and his brother Chris Oldfield under a Coolabah tree. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

There is an upside to having no river regulation: Craig can count on floodwaters staying in the system and, as long as there's enough, it will reach Cowarie.

Craig watched the Queensland floods and when he saw how much water was on its way, he knew they'd be alright.

"We would have sold up our cattle by now, probably [be] on a pretty severe destock plan, and now we've got a restock plan," Craig says.

"It is a bit of a tragedy the way this flood started, and you can feel the loss of the producers and the graziers up north."

What devastated the cattle industry at the head of the river system, has saved graziers like him downstream.

"You do feel for them, but it is opportunity country and you have to take it. Just doesn't matter how it comes," Craig says.

Photo:

Jim Smith moves beer into his pub, the Royal Hotel, in Bedourie. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Photo:

Jim Smith moves beer into his pub, the Royal Hotel, in Bedourie. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

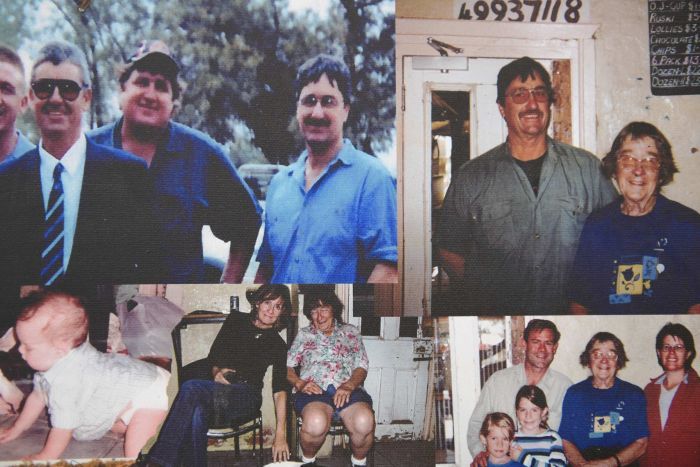

For Jim Smith, there's nothing worse than a dry pub in the middle of a flood.

The Bedourie publican has run out of beer on numerous occasions when the town has been cut off — the record is 14 weeks.

The government will subsidise essential food items to be flown in, but alcohol isn't included.

"They say it's not an essential item, but I think those people haven't been in Bedourie when we run out," Jim says with a laugh.

"It's much worse than running out of food."

Jim's family took over the Bedourie Hotel in 1971, three years before the biggest flood on record.

It inundated the house across the road from the hotel and sent hundreds of snakes out of the bush and into the town looking for higher ground.

"They were everywhere," Jim says.

"I heard my Mum scream and I thought she'd been bitten so I raced to the kitchen. As she'd come out, a snake had gone in."

The floods are bad for business, but Jim is a patient man.

The main road into Bedourie has been cut off, but Jim knows the visitors will come, along with the new life the flood brings.

While others work to make the most of the water, Jim waits for it to subside.

Ready to protect

The residents of the Lake Eyre Basin have fought before to protect the rivers which feed this globally unique ecosystem and they stand ready to do so again.

Mark and Tess McLaren are already fighting. They manage the Kalamurina Wildlife Sanctuary for the Australian Wildlife Conservancy.

The region was once home to species such as the lesser bilby and the pig-footed bandicoot, mammals that are now presumed extinct.

Photo:

Mark and Tess McLaren live on Kalamurina and work to regenerate the land. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Photo:

Mark and Tess McLaren live on Kalamurina and work to regenerate the land. (ABC News: Brendan Esposito)

Mark says they are "all about the little mammals" and "the biggest thing is keeping the ferals in check".

They hunt and trap feral cats, foxes, wild dogs and camels, uproot weeds and restore native vegetation on the former cattle station.

They also remove any barriers to the river's natural flow, left over from the property's former life.

Tess insists the rivers do all the hard work for the environment, "all we have to do is leave [them] run".

Across the entire basin, people know this flood is just a moment in a boom and bust cycle.

In a few months' time, the water will disappear. Seep into the ground and evaporate into the air.

Gone, but living on in the people, plants and animals that rely upon its life-giving force, and in the stories told and memories made each time these unique desert rivers run their course.

Credits

Reporting: National rural and regional correspondent Dominique Schwartz

Photography: The Specialist Reporting Team's Brendan Esposito

Videography: The National Regional Reporting Team's Ben Deacon

Editing and digital production: The Specialist Reporting Team's Emily Clark

Topics: lifestyle-and-leisure, rural, environment, rivers, water, water-management, environmental-management, ecology, australia, bedourie-4829, birdsville-4482

First posted