The Rojava Revolution – Radical democracy, womens liberation and ecology.

The Rojava Revolution – Radical democracy, womens liberation and ecology.

Here you find background informations and further links about the rojava revolution:

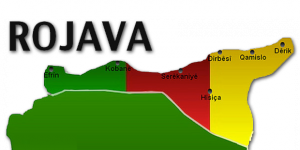

Rojava

The Charter of the Social Contract is the provisional constitution of the autonomous region of Rojava. It was adopted on 29 January 2014, when the people of Rojava declared the three Rojavan cantons (Efrin, Kobane and Cizire) autonomous from the Syrian government.

In 17 March 2016 by 31 parties and 200 delegates representing Rojava’s Kobane, Afrin and Cizire cantons and the Kurdish, Arab, Assyrian, Syriac, Armenian, Turkmen and Chechen peoples of Girê Spî (Tal Abyad), Shaddadi, Aleppo and Shehba regions the Constituent Assembly for the establishment of the Rojava-Northern Syria Democratic Federal System has ended with the Final Declaration.

For actual political positions of the Democratic Self Administration of Rojava (DSA) look at their paper with the name Save Haven in Syria

TEV-DEM (Tevgera Civaka Demokratîk / Movement for a Democratic Society, Rojava / Northern Syria), the umbrella body of the administrations of Rojava, released an important document called The Project of a Democratic Syria, in which they lay out a proposal for the peaceful resolution of conflict Syria and a new political vision for the country as a whole.

A new book was published in March 2015 by Strangers in a Tangled Wilderness , entitled A Small Key Can Open A Large Door: The Rojava Revolution. The introduction to that book has been made available as an online zine and is an ideal one-stop-guide for people who want to know how the revolution in Rojava came about. It is available for download as a pdf.

Kurdistan National Congress (KNK) Information File, published May 2014: Canton Based Democratic Autonomy of Rojava: A Transformation Process From Dictatorship to Democracy.

The Democratic Autonomous Administration of Rojava released a peace proposal for ending the conflict in Syria in May 2014, called Kurdish initiative for a democratic Syria.

The founding document of the Democratic Autonomous Administration of Rojava, Charter of the Social Contract, Rojava Cantons, 29 January 2014.

Statement by the Kurdish Community Centre, Halkevi Turkish and Kurdish Community Centre, Sussex Kurdish Community Centre, Peace in Kurdistan Campaign & Campaign Against Criminalising Communities (CAMPACC), 14 February 2014: Peace, equality and self-determination: The Kurds take the lead in proposing a new way for Syria,

Norman Paech, Emeritus Professor of Human Rights and former foreign policy spokesman for Die Linke, breaks down Turkey’s hypocritical approach to Syria and it own Kurdish opposition movements in In the Glasshouse.

David Morgan’s articles for Live Encounters, The Mirage of ISIS and The struggle against ISIS in historical perspective are both excellent reviews of regional and global political dynamics following the rise of ISIS in Iraq and Syria.

Dilar Dirik, The ‘other’ Kurds fighting the Islamic State, published in Al Jazeera at the height of the Kobane resistance, asks why the ‘other’ Kurds of Syria (and their counterparts in Turkey) are still labeled as terrorists even while their superiority fighting ISIS became widely acknowledged.

Yvo Fitzherbert excellent reporting from the region shows how Ocalan’s ideas influenced the Rojava revolution and questions Turkey’s disruptive policies towards the Kurds. His later article, published in February 2015, delves into how Turkey’s unquestioning support for the Syrian opposition is effecting the Syrian refugees it is hosting.

VIDEO: BBC News documentary, Syria’s Secret Revolution, released in November 2014, goes behind the front line fighting in Kobane to look at the social revolution taking place across Rojava.

Delegations have visited Rojava in recent months to offer solidarity to the struggle, find out more about what is happening and raise awareness of the revolution back in Europe. Janet Biehl took part in one such delegation organised by Civaka Azad and wrote this report on her return, Impressions of Rojava: A report of the Revolution, as well as providing further and more detailed eye-witness accounts of democratic autonomy in action. The whole group also published a collective statement in which they report that genuine democratic structures have been built in Rojava, which they believe can show a new way forward for Syria and the Middle East.

For anyone questioning whether the revolution is Rojava is genuine, David Graeber, anthropologist and political activist who took part in the delegation, answered the question clearly on his return.

Dr. Jeff Miley and Johanna Riha summarise their observations from their visit to Rojava, and they discuss how democratic autonomy transcends state borders, integrate gender emancipation and has involved impressive mobilisation in all sections of society. Dr Miley also gave a talk at the University of Cambridge recently, titled, Can the revolution in Rojava succeed? which you can listen to below:

Peace in Kurdistan Campaign has also organised delegations to the region, and published several of the delegate’s reports once they returned.

Zaher Aarif travelled to North Kurdistan in November 2014 to find out more about the social revolution sweeping the region. He wrote about his visit for Anarkismo, where he describes how Kurdish institutions in the south of Turkey are operating autonomously in order to deal with the refugee crisis and continued attacks on the Kurdish people north and south of the border, just like in Rojava. Zaher notes that the social revolution taking place has come from local organisation of ordinary people on the ground.

Following the announcement on 26 January 2015 that Kobane had been liberated of ISIS troops, Trevor Rayne wrote that the Victory in Kobane was down to the will, determination, organisation and skill of the YPG and YPJ troops, and called for their affiliated organisation, the PKK, to be delisted.

Dilar Dirik explains why Kobane did not fall, and how the vision of the Kurdish movement led the resistance of Kobane to success.

Here is an article by Johannes de Jong in the Stream on the current state of Rojava, April 2016. A New , Free Middle East Is Rising from the Ashes of Syria’s Civil War. Why is Geneva Ignoring Them?

Kurdistan: a brief history

It was in the 1980s when the historian Gwyn A Williams posed the famous question, When was Wales? This begged more questions: What constitutes a nation? What are its origins? What does it matter? This attempt to understand “the national question”, prompted by a reading of Gramsci, raised a series of key issues that could be asked of any national struggle for liberation and became the agenda was an urgent one for a Marxist such as Williams who ended up as a progressive nationalist and supporter of Plaid Cymru, the Party of Wales.

It is not coincidental that the Welsh people have long been some of the most passionate supporters of the rights of the Kurds, because some of their fundamental demands and experiences are shared just as they are shared with subject people everywhere. Common demands include respect for their distinct identity as a people, the freedom to enjoy their own culture, to express themselves in their own language and the ability to exercise local control of resources. This latter point in the Welsh case manifests itself in devolution and in the contemporary Kurdish case in the recent proposals for “democratic autonomy”. These and other key demands are ones that Kurds share with all the other nations who found themselves on the losing side when the national borders were drawn up by the major imperial powers and reshaped the modern world; with regards to the Kurds, this process occurred particularly in the aftermath of the First World War and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. The Kurds are still suffering the consequences of that settlement which failed to take account of their rights or existence; and this is where the roots of the modern Kurdish conflict lie.

So when was Kurdistan? As a name for a country it is thousands of years old and as a name it is much older than the word Turkey which first emerged as a name for a modern country only in the 20th century. On old maps of the region Kurdistan always features and was only erased following the international agreement that led to the carving up the region in the aftermath of the First World War. The founder of the Turkish Republic Mustafa Kemal Ataturk is still widely lauded by commentators and historians as one of the greatest nation builders of modern times, but this is to completely ignore the brutal measures that had to be employed to achieve his vision of turkification. The construction of contemporary Turkey in large part marked the removal of Kurdistan from the pages of history and as a people their very existence has been denied and all traces of their culture, language and history are intended to be forgotten at least as far as the ruling Kemalist nationalist ideology is concerned. Indeed, historic maps depicting evidence of Kurdistan were to be banned in Turkey as the existence of the Kurds could not be tolerated along with all other peoples whose awkward presence challenged the principles of its dominant ideology.

While the idea of a land called Kurdistan and the sense of a Kurdish identity lived on in the hearts and minds of Kurdish people, cherished despite all the forced assimilation with which they have been assailed, Kurdistan only really emerged as a major political cause once more with the growth of the modern Kurdish national movement in the 1980s. (Kurdish populations are in fact dispersed across four major nation states of the Middle East; namely, Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey. Our focus is on Turkey primarily, the reasons being that this country has by far the largest Kurdish population, it is the country where fundamental rights for the Kurds are most flagrantly denied; importantly, it is the country where a major Kurdish social and political movement has emerged over the last 30 years and finally as a state Turkey enjoys special relations with Europe and America through NATO and its accession talks with the EU).

There are several key dates in the history of Turkey and the struggle of the Kurdish people for their liberation. One such watershed year was 1980 when the 12 September military coup headed by General Evren led to a brutal crackdown on protests and progressive forces during which hundreds of thousands of people were detained, tortured and executed by extra-legal means; a reign of terror by the ruling military ensued whose conduct was especially brutal in the Kurdish region of the country. Two years later the Turkish generals imposed a new constitution on the country which placed strict restrictions on civil and human rights.

The first election following the military coup occurred in November 1983 and saw Turgut Ozal become prime minister. The following year witnessed the start of the guerrilla campaign initiated by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party to achieve the freedom of the Kurdish people. Brutal clashes with the Turkish military were to go on for years and there are many thousands of casualties. In Western news reports the PKK is always held responsible for these casualties, numbering approximately 40 thousand, while the responsibility of the Turkish armed forces is less closely examined. The official version of events put forward by Turkey has invariably been accepted as the unvarnished truth by journalists reporting far away from the conflict zone. Thus statements and commentaries issued by the Turkish government are digested uncritically and find their way into news reports which in effect repeat the opinions of one side as fact. Reporting on the conflict is further distorted by the restrictions on the media inside Turkey in general which have prevented independent investigative journalism from corroborating claims made by the authorities about incidents and has meant that the truth has become suppressed as a matter of routine. Journalists are certainly not free to operate as they wish in the Kurdish areas and in particular they are not permitted to visit the scenes of clashes making it virtually impossible to verify claims made by Turkey about casualties or establish details of what took place. As such, the true scale of the atrocities committed by agents acting on behalf of the state, by the Turkish army and counter-terrorism personnel will probably never be fully established.

In 1989, the year that witnessed the fall of the Berlin Wall marking the symbolic end of Communism in Eastern Europe, Ozal became the first civil president of the Turkish Republic. Counter-terrorism operations against the Kurds were stepped up and human rights abuses continued unremittingly.

The 1990s has been described as a lost decade and was certainly one of the darkest periods in the history of Turkey. This was a decade when the economy was in the doldrums and when the rule of law appeared to have been set aside as the state pursued a dirty war with few limits against the Kurds. The conflict between the state and the Kurds expanded to embrace the whole of Kurdish society and Turkey became divided into two entirely separate regions with the Kurdish south east resembles a huge militarised camp. On the economic front, these years led to increasing poverty and mass migration especially from the Kurdish regions; thousands claims asylum in countries of Europe, particularly, Germany, Sweden and the UK, but many more Kurds, deliberately displaced from their villages and dispossessed of their farmlands, were forced to migrate to the main Turkish cities where they established makeshift homes on stretches of wasteland on the margins.

Casualties continued to mount as the war reached new heights of intensity. A notorious massacre of dozens of Kurdish mourners at the funeral of Kurdish political activist Vedat Aydin occurred in Diyarbakir in 1991 when Turkish counter-terror forces fired into the crowd. Meanwhile, in 1992, the Kurdish town of Sirnak was razed by the Turkish army in reprisal for a PKK attack. This incident remains symbolic of the “scorched earth” policy carried out by the Turkish military during this period.

The assassination of opponents of the strategy pursued by the state became more frequent. Victims include journalists investigating the hidden powers exercised by the “deep state” in ruthless pursuit of its anti-Kurdish campaign. Counter-terrorism agencies at this time sponsored the Islamist Hizbullah organisation in carrying out a campaign of murder and assassination against prominent Kurdish social figures, community leaders, businessmen and intellectuals.

The well-known Kurdish writer and journalist Musa Anter was one of the victims of assassination in September 1992 while a leading Kurdish trade union activist, Zubeyir Akkoc was killed in January 1993 and MP Mehmet Sincar was murdered in September of that year. These are just a few of the victims of a brutal Turkish policy that has involved mass murder and wholesale ethnic cleansing.

In the face of such major human rights violations and atrocities, it is in fact quite remarkable that the Kurds have remained steadfast in their demands for peace and reconciliation, appearing to bear little ill will against their Turkish neighbours. This position can be attributed to the mature political leadership of the Kurdish side, whose perspective is based on a realistic understanding of the functioning of the state and social relations. They are able to distinguish between the actions of the state and the opinions of the people and seek a political solution to the conflict which will allow the Kurdish and Turkish people to live together in peace, freedom and equality.

Suspicious circumstances surrounded the plane crash in February 1993 which killed General Bitlis, the commander of the Gendarmerie, who was known to be seeking to find a solution to the Kurdish question. Two months later President Ozal himself died unexpectedly of a heart attack, which sparked rumours of an assassination.

During the presidency of Suleyman Demirel and Prime Minister Tansu Ciller the military offensive against the Kurds was greatly intensified. The Kurdish provinces are put under a state of martial law and covert counter-terrorism operations become the norm. Thousands were detained, tortured and murdered as the state colluded with the military in a dirty war that saw mafia bosses, contract killers, drug dealers, informers, agents and provocateurs working in concert to defeat the Kurds.

It needs to be stressed that Turkey military conducted its counter-insurgency measures with extreme brutality. Atrocities were systematic; torture was widespread, whole communities were subject to a reign of terror, civilians could be picked up at random, innocent men, women and children were routinely tortured and many disappeared. People were “disappeared” and bodies were dumped into mass graves in secret locations. Meanwhile, in the field of battle, the bodies of captured guerrillas were found grotesquely mutilated with Turkish soldiers displaying body parts as trophies in photographs.

The dismemberment and mutilation of bodies has continued right up until today with the latest incident occurring during the renewed conflict that flared up in the aftermath of the 2011 general election. Photographs of four dismembered bodies of some 24 Kurdish guerrillas who died in clashes with the Turkish army were made public in October 2011. The savage method of their killing and mutilation of the bodies clearly evident from the photographs shocked the Kurdish community and was denounced as a war crime by Selahetin Demirtash, the co-chair of Peace and Democracy Party (BDP). “Both the photos of the bodies and the information we received show that all the bodies were subjected to torture and torn apart. This is savagery and a war crime and those responsible for this pain are those who act with the feeling of revenge,” Demirtash was quoted as saying. The BDP leader went on to describe the brutal action as going beyond the realms of war and was evidence of such hate that cannot be explained.

On 5 November 1996 the notorious Susurluk incident took place and exposed this close collaboration between politicians, police, the security apparatus and the criminal underworld in their counter-insurgency campaign against the Kurds. Susurluk was to be the downfall of Prime Minister Ciller who chose to honour the dead as patriots.

In 1997 the government of the Islamist PM Erbakan was forced to resign under pressure from the military. Erbakan’s Welfare Party was later banned by the constitutional court and was re-established as the Virtue Party. The current Justice and Development Party (AKP) emerged from the reformist wing of this party. The AKP has come to dominate Turkish politics since its sweeping election victory in 2002. With the rise of the AKP as a moderate face of Islam, Turkey has come to be seen in the West as an example of a successful compromise between Islam and democracy and held up as a model for emulation in the wider Middle East. Despite an improved image, considerable economic success, the enactment of reforms, and the moves towards a new constitution under the leadership of Prime Minister Erdogan and the AKP, resolution of the Kurdish conflict has not only remained elusive, it has become deadlocked. Despite making great paly of an “opening” towards the Kurds, Erdogan has in fact pursued a two-pronged strategy of small, piecemeal reforms while seeking to eliminate the independent voice of the Kurds. Such a policy has been deemed at best inadequate and at worst duplicitous. It has failed to convince or satisfy the Kurdish people and has not sought to meet and address any of their major demands with any degree of seriousness.

Waves Kurdish activists, prominent intellectuals, writers, academics, lawyers as well as leading members of the main pro-Kurdish legal political party the BDP, have been arrested and charged for alleged terrorist sympathies, particularly following the June 2011 general election when the BDP candidates won significant support. The ongoing arrests and prosecutions expose the tremendous difficulties for the Kurds of engaging in normal constitutional politics within Turkey. It is worth mentioning that the BDP is the latest in a series of pro-Kurdish parties that have been established over the last twenty years. At least five previous parties, which had all received significant voter support, have been closed down by the Turkish courts following prosecutions, arrests, harassment and police raids which have become a matter of routine. The previous parties include the People’s Labour Party (HEP), closed in 1993; the Democracy Party (DEP) closed in 1994; People’s Democracy Party (HADEP) closed in 2003; the Democratic People’s Party (DEHAP) closed in 2005 and the Democratic Society Party (DTP) closed in 2009. It is a tribute to the skills and persistence of the Kurdish politicians that they have to date managed to success manoeuvre around the bans and in the process achieve rising levels of support from the people. But the measures taken to block their effectiveness are outrageous and warrant strong criticism from the Western democracies, and particularly from countries in the European Union, who like to take on the role of upholders of democracy overseas.

The most memorable date in recent Kurdish political history is undoubtedly 15 February 1999 as this was the day when PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan was captured in Kenya by Turkish special forces personnel operating undercover. The circumstances surrounding Ocalan’s arrest are rightly regarded by the Kurds as an international conspiracy because of the clearly coordinated actions of security personnel (CIA, Mossad and MI5) and politicians from various countries which lured Ocalan into a trap after he was denied the right to claim political asylum in Europe (in flagrant violation of international human rights law)..

Turkey’s success in capturing their “Enemy Number One” was broadcast before the world’s media in an attempt to humiliate both Ocalan and the Kurdish people as a whole. The spectacle was a grotesque act of triumphalism on the part of Turkey and only served to exacerbate tensions between Turks and Kurds. It set off a wave of spontaneous actions by Kurds within Turkey and among the diaspora communities across Europe.

During his trial, which was very much a show trial of dubious legality in many respects and later deemed as such, Ocalan conducted himself with great dignity, statesmanship and imagination as he sought to explain the Kurdish case historically and in continued to pursue a policy of peace and reconciliation, which he had adopted long before his arrest. It has often been remarked upon that Ocalan has remained steadfast and has persisted in his pursuit of constructive peace proposals from the courtroom and prison cell despite the tremendous provocations and in the face of the often frenzied triumphalism of Turkish nationalists bent on a total victory over the Kurds. The quality of leadership demonstrated by Ocalan could be used constructively to achieve a peace settlement if only Turkish leaders and their allies would set aside their prejudices and become sufficiently proactive to see it as an opportunity to resolve a conflict that has lingered on for far too long. Ocalan urged Kurdish guerrillas to cease their military actions and to fall back to defensive positions outside the country, to which they responded; meanwhile, in reaction to an outbreak of incidents involving young supporters setting themselves on fire, Ocalan strongly expressed his disapproval of such methods and called upon Kurds not to sacrifice themselves on his behalf.

While in prison Ocalan has produced several proposals for achieving a peaceful conclusion to the conflict, including the roadmap, which the Turkish authorities initially withheld from the public, and culminating in proposals for “democratic autonomy”. All his ideas have been released through his lawyers, who have been subjected to intimidation and prosecution themselves simply for carrying out their professional duties. Since his conviction, Ocalan has also produced three substantial volumes, which have been published in book form in English; in these pages Ocalan has sought to offer constructive and conciliatory arguments for a lasting settlement. So far there has been no serious response from the Turkish side to any of his proposals; despite the reports in 2011 that talks were being held between Ocalan and Turkish officials nothing substantial has yet resulted. Meanwhile, clashes between the army and guerrillas have renewed in intensity with the Turkish side launching a major operation against Kurdish encampments across the border in Iraq in the autumn of 2011.

At the time of writing, Turkey is seeking to enlist the support of Kurdish Regional authorities in Iraq in its bid to eliminate the PKK camps stationed on its soil. Turkey’s Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu called upon Kurdish leaders in Iraq to cooperate, issuing a veiled threat saying that Turkey would have every right under international law to enter its territory to stop the PKK. “Turkey cannot let an entity that constitutes a clear and direct threat against itself to exist right across its borders,” the foreign minister was quoted as saying. “The northern Iraqi administration should stop this terrorist entity and cooperate with us. Otherwise we will enter and stop it,”(Sunday’s Zaman, 30/10/2011).

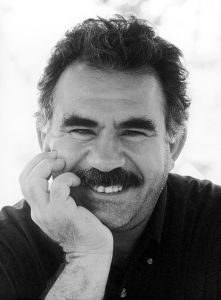

Abdullah Öcalan

Abdullah Öcalan is regarded by millions of Kurds as their political representative, and has become the key figure in their struggle for cultural rights and democracy.

An integral figure in the burgeoning Kurdish nationalist liberation movement in the 1980’s, he founded the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), the armed wing of the Kurdish struggle for autonomy, in 1978. From 1984, the PKK fought for an independent Kurdish state in southeast Turkey, in a sustained popular uprising in which thousands of PKK guerrillas have fought the Turkish army, the second largest in NATO.

In 1999, Öcalan was captured in Nairobi and sentenced to death under Article 125 of the Turkish penal code, and when Turkey abolished the death penalty in support of its bid for EU membership, Öcalan’s sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. For the first 10 years in jail, Öcalan lived in solitary confinement as the sole prisoner on the island of Imrali, a condition that was temporarily lifted by the Turkish Authorities as it engaged with secret negotiations with the PKK in 2011. On 28 December 2012, the Turkish government announced that they had begun talks with Ocalan in order to bring about an end to the conflict.

Despite these conditions, Öcalan has continued to work actively for a resolution to the conflict, writing numerous books and articles on the history of the Kurdish people, the sources of the conflict and possibilities for peace. Having long abandoned separatism in favour of a new form of democratic confederalism, his nuanced analysis has led him to contribute important proposals for democratic reform of the Turkish state, including, in 2011, The Road Map to Democratisation in Turkey, and Solution to the Kurdish Question. The text was illegally confiscated in 2009 by the Turkish authorities, who refused to release it to the European Court of Human Rights, as was intended, for 18 months

Information on Abdullah Ocalan and some of his writings, including his pamphlets which are available in pdf format, can be found here:

www.peaceinkurdistancampaign.com/resources/abdullah-ocalan

Ocalan has written several books, only some of which have been translated into English:

- Prison Writings Volume I: Roots of Civilisation, Abdullah Ocalan. January 2007

- Prison Writings Volume II: The PKK and the Kurdish Question in the 21st Century, Abdullah Ocalan. March 2011.

- Prison Writings Volume III: Roadmap to negotiations, Abdullah Ocalan. January 2012.

- All publications can be found at: ocalan-books.com

A review of all three Prison Writings by Felix Padel provides useful insights into the relevance of Ocalan’s work: The Kurdish Quest of Countering Capitalism to build a Democratic Civilisation

Further writings by Ocalan and documents relating to his imprisonment can be found here: www.freedom-for-ocalan.com/english

A campaign for Ocalan’s freedom from Imrali prison has been on going for several years: www.freeocalan.org

Kurdish Womens Movement

The KJB (Koma Jinên Bilind, translated as the High Women’s Council) is an umbrella organization of Kurdish women’s organisations. Their website features an article, The Kurdistan Women’s Liberation Movement for a Universal Women’s Struggle, which explains the history and expansion of the Kurdish women’s movement.

Abdullah Ocalan’s booklet, Liberating Life: Women’s Revolution is available as a pdf and is an essential read. Here he analyses the centrality of women’s liberation from patriarchy in the struggle for a fully liberated society.

VIDEO: Dilar Dirik, Stateless Democracy: How the Kurdish Women Movement Liberated Democracy from the State (Paper given at the New World Summit in Brussels, 21 October 2014).

Kobane: the struggle of Kurdish women against Islamic State is a useful article published in Open Democracy in October 2014 on the involvement of Kurdish women in the liberation of Rojava and the fight against ISIS.

Margaret Owen reports back following her visit to Rojava in December 2013. Her article, Gender, justice and an emerging nation: My impressions of Rojava, was published in Ceasefire Magazine soon afterwards.

Mary Davis, trade unionist and academic, spent 10 days visiting women’s groups in northern Kurdistan (Turkey) in July 2012 as part of a delegation organised by CENI.

Dilar Dirik’s 29 October article for Al Jazeera, Western fascination with ‘badass’ Kurdish women, goes beyond the western media’s orientalising narrative of Kurdish women fighters in the YPJ to examine the history of women resistance fighters and their place in the PKK.

CENI – Kurdish Women’s Office for Peace, based in Germany, released this Dossier on the Assassination of Three Female Kurdish Politicians in Paris following the assassination of Sakine Cansiz, an icon of the Kurdish struggle for liberation, and two more of her activist colleagues. They were killed in broad daylight in the centre of Paris in early January 2013, just weeks after peace talks between the Turkish government and the PKK were announced.

Roj Women’s Association, based in the UK, published this report in May 2012 which looks at state violence toward women human rights defenders in Turkey: A Woman’s Struggle: Using Gender Lenses to Understand the Plight of Women Human Rights Defenders in Kurdish Regions of Turkey

Democratic Autonomy

BOOK: Democratic Autonomy in North Kurdistan: The Council Movement, Gender Liberation, and Ecology by TATORT Kurdistan and Janet Biehl (New Compass, 2013)

TATORT Kurdistan also wrote this article, Democratic Autonomy in Rojava, following a 2-month visit to Rojava.

Janet Biehl, Bookchin, Ocalan and the Dialectics of Democracy (Paper given at the conferenceChallenging Capitalist Modernity–Alternative Concepts and the Kurdish Quest, which took place 3–5 February 2012 in Hamburg University.

Alexander Kolokotronis delves into the theoretical underpinnings of Democratic Autonomy, in The No State Solution: Institutionalizing Libertarian Socialism in Kurdistan.

This article by Rafael Taylor published in August 2014, The new PKK: unleashing a social revolution in Kurdistan, is a useful exploration of Ocalan’s ideas and the theory and practice of democratic autonomy in Rojava.

Michael Knapp explains how the cooperative and democratic economic model being developed in Rojava offers possible emancipation from both capitalist and feudal systems of exploitation.

A conference was held in Hamburg in April 2015 called Dissecting Capitalist Modernity, which brought together scholars and activists from across the world to unpack contemporary capitalism and discuss alternatives, like the ones presented by Ocalan and the Kurdish movement. Participants included International Initiative’s Havin Gunesser, scholar Dilar Dirik, Prof. David Graeber, PYD co-chair Asya Abdullah, MP Selma Irnak, Dr Radha D’Souza, and prominent Marxist geographer Prof David Harvey. The conference included sessions on democratic autonomy as well as lessons from around the world, such as Mexico and Venezuela. The papers and videos are available on the dedicated conference website.