Capitalist restoration in Russia: A balance sheet

Part 3

By

Clara Weiss

3 May 2018

This is the third article in a four-part series. Here are links to Part 1, 2.

The Trotskyist warning that the Stalinist bureaucracy, unless stopped by the working class, would eventually move to destroy the degenerated workers’ state and become a new property-owning class was fully confirmed by what happened in the 1990s.

One Russian sociologist described the process quite pointedly:

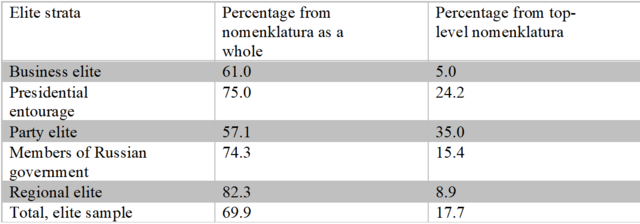

“A minister became the holder of controlling shares in a concern; an administrative head in the Ministry of Finance became the president of a commercial bank; a senior manager in Gossnam [the former Soviet agency responsible for distributing the ‘means of production’] became the chief executive of the stock exchange.” [16]

The open criminality of the new bourgeoisie was stunning. According to a survey among Cheliabinsk entrepreneurs in the early 1990s, 30 out of 40 possessors of large holdings considered it impossible to do business without breaking the law; 90 percent were convinced that they couldn’t engage in business without giving bribes to various state agencies; 65 percent had bribed workers in financial auditing bodies and 55 percent had bribed deputies at various levels.

In a private conversation with the economist Anders Aslund, who helped elaborate and implement “shock therapy”, one of the oligarchs who came to wealth and power during the loans-for-shares privatization of the mid-1990s explained,

“There are three kinds of businessmen in Russia. One group is murderers. Another group steals from other private individuals. And then you have honest businessmen like us who only steal from the state.” [17]

This perverse and criminal orgy of self-enrichment by former bureaucracy was based on the destruction of the productive forces that had been created by the Soviet working class, and the reckless and short-sighted selling-off of raw materials. The Kuzbass and the Russian coal industry are a particularly stark example for the social criminality and ruthlessness of this process.

After the United States, Russia has the world’s largest coal reserves. The remnants of the Soviet coal industry were thus among the most tempting parts of the booty that both Russian and Western businessmen hoped to secure during the capitalist restoration. The US had already laid the basis for a massive intervention with the above documented PIER project launched in 1990, well before the final destruction of the USSR in late 1991. Throughout restoration and much of the 1990s, the US remained heavily involved in the so-called “restructuring” of the Russian coal industry.

In the first years of capitalist restoration, the government, while privatizing the coal industry, backed away from cutting all of its subsidies, largely out of fear of a renewed explosion of the struggles of the coal miners, who continued to go on strikes throughout the 1990s. The coal industry also remained under the administration of the former Soviet ministry Rosugol, whose president, Yuri Malyshin, numbered among the most powerful figures at that time. While already completely privatized, the fact that the coal industry was under the de facto control of one large Russian state-business entity could not but be a thorn in the side of international, and especially American, finance capital.

The main lever through which the complete subordination of the coal industry to the profit interests of large American, Australian, Austrian and Russian companies was guaranteed, was the World Bank. Determined to send the Russian coal industry along the “Thatcher route”, the World Bank outlined a program of massive cuts and mine closures as a condition for a $500 million loan. The Russian government for whom the coal industry was, according to one author, a “political noose around its neck”, accepted the “proposals” of the World Bank in 1995, which included the “zeroing out” of all coal subsidies, and a plan to cut employment in the coal industry in half within three to five years.

The World Bank’s program was closely tied to the US-funded Coal Project, and both were fully supported by the independent miners union, the NPG, which by then had lost much of its membership and influence.

The impact of the “restructuring program” on the coal industry was devastating. Coal mining employment in Russia plunged from 900,000 to roughly half that by 2000. Production, which had peaked in 1988 with 400 million tons, dropped to just 225 million in 1997. Rosugol became an open-type joint-stock company in 1996, with Malyshev as its president. In 1998, after the closure of at least 58 mines, the government announced plans to shut down another 86 out of the remaining 200 coal mines in Russia.

Workers were going without wages for months and even years. While this was a general phenomenon in the Russia of the 1990s, the situation was particularly dire in the coal industry. In one particularly infamous case, the Kuznetskaya mine in the Kuzbass, one of the largest iron mines that had been privatized in 1991 as a joint-stock company with an Austrian firm, did not pay its workers for two years. Driven by despair, miners and their wives eventually resorted to locking the mine’s top management in their office and holding them hostage until their wages were paid.

Coal workers, once the most highly paid group within the Soviet working class, dropped to seventh place by the late 1990s. [18]

Like aluminum, steel and other raw material and energy industries, the coal industry was the subject of violent battles within the state, and among the rising oligarchs and organized crime, with the lines between these three sectors being all but non-existent. Dozens of Kuzbass mine managers were assassinated as part of the mafia wars in the 1990s. The Kuzbass had the third-highest murder rate in the nation. One mine director who was asked by the Moscow Times about the influence of organized crime on the coal business, answered briskly: “They don’t influence it. They run it.”

The social disaster resulting from the mine closures and elimination of hundreds of thousands of jobs was aggravated by the fact that, due to a serious housing shortage in Russia (which is still ongoing), it proved all but impossible for laid-off miners to move with their families to different regions to find other employment. One local government official from the Kuzbass who had formerly worked for the KGB laconically told the New York Times: “These days they [the coal miners] don’t care about soap. They want food.”

Strikes by the miners in the Kuzbass and beyond occurred throughout the 1990s, drawing in between 400,000 and 600,000 miners. Overall, millions of workers continued to go on repeated strikes throughout this period, protesting against the extreme social crisis. However, under conditions of extreme political confusion, these strikes could be manipulated and exploited by rival factions within the unions and among government officials and businessmen, who were trying to use the striking workers in order to push for their own interests in Moscow or the region.

While very stark, the situation in the Kuzbass is broadly representative of the political and economic chaos, the criminality and the social despair that have come to mark the 1990s more generally, a period which many Russians, for good reason, still remember as traumatic.

According to the Russian journal Expert, total industrial production in Russia collapsed by as much as 55 percent in the 1990s. By comparison, during the Great Depression in the US, production declined by 30 percent. In Russian history, only the combined effect of WWI and the Civil War after the October Revolution had been worse. Between the first half of 1993 and the first half of 1994, industrial production in sectors like armaments, electronics and construction – key industries of the Soviet Union – declined by 40 to 50 percent. Industrial production as a whole in 1994 was 47 percent of its 1990 levels. Domestic investment was 35 percent of its 1990 level by 1995, and in 1996, 75 percent of all companies didn’t make any capital investment at all. Foreign capital would flow to the stock markets and financial institutions, but not into industry.

Privatization and the dismantling of substantial sections of industry also meant the destruction of a social welfare state that was in large measures tied to the Soviet industrial infrastructure.

Moreover, the past few decades have seen relentless cuts to the health care system, in particular. The social crisis and lack of any political perspective have driven millions into suicide, and into drug and alcohol abuse.

Social infrastructure has been neglected to an extent that is patently criminal. In Russia, by territory the largest country in the world and with a population of 140 million, there are only some 5,000 fire stations. The much smaller – and socially also devastated Poland – has over 15,000 for a population of 40 million. In 2014, 9,405 people died in fires in Russia. The number of dead per 1,000 fires was 64.5, a rate surpassed only by Belarus which had 78.8 dead per 1,000 fires. By comparison, in the US, which has a population of 320 million, 3,280 people died in fires with a death rate of 1.7 per 1,000 fires.

The March 25, 2018 Kemerovo fire was one of the worst, but hardly the only major fire that was caused by the criminal disregard of basic fire safety regulations. In 2003, a fire in a student dorm of Moscow University took the lives of 44 people, injuring 156; a fire in a nursing home in Krasnodar in 2007 killed 60 people; a fire in a nightclub in Perm in 2009 killed 154; and, in 2015, a fire at a mall in Kazan killed 19 people, and injured 61.

Every year, an estimated 15,000 workers die in workplace accidents, according to numbers of the International Labor Organization. A horrifying 190,000 workers die annually as a result of exposure to dangerous conditions at work.

In short, contrary to the claims of capitalist triumphalists and most bourgeois academics, the restoration of capitalism was anything but “peaceful.” It was a one-sided class war in which the working class, disarmed and beheaded by decades of Stalinism and the intervention of Pabloism, was bitterly attacked by both the rising oligarchy and imperialism.

The death toll of this counterrevolution has never been drawn up. But any serious estimate would have to take into account not only the tens of thousands who died in the civil wars which erupted in the Caucasus and Central Asia; but also the over one million suicides in Russia alone since 1991; the horrific spike in deaths from previously eradicated diseases like tuberculosis; the millions of victims of the ongoing heroin and HIV epidemic; the tens of thousands of workers who have died in workplace accidents; and the many millions of victims of the decrepit state of the social infrastructure and the health care system. The Kemerovo fire adds another 60 people to this account, but it is in many ways only the tip of the iceberg.

Only a tiny oligarchy and a very small upper middle class have benefited from this criminal process. The Credit Suisse global wealth report for 2016 revealed that among all major economies, Russia had by far the highest concentration of wealth in the hands of an oligarchy. The report found that the top decile owns a stunning 89 percent of all household wealth in Russia, compared to 78 percent in the United States and 73 percent in China. 122,000 individuals from Russia belong to the world’s wealthiest 1 percent, and the country has no less than 79,000 US-dollar millionaires. Russia also has the world’s third largest number of billionaires, 96, topped only by the 244 living in China (which has almost 10 times the population of Russia) and the 544 billionaires in the US. Only about 4 percent of the population qualified as “middle class.”

By contrast, according to an article in the Nezavisimaya Gazeta from April 2017, some 56 percent of Russian workers make less than 31,000 rubles ($531) a month. The official subsistence level was recently lowered by the government to less than 9,691 rubles ($166), a wage that is impossible to live on. Official statistics indicated that the number of extremely poor people, living beneath this low threshold, stands at around 19 million.

To be continued

Notes:

[16] Olga Kryshtanovskaia, “Transformation of the Old Nomenklatura into the New Russian Elite”, in: /Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost’/, 1995, no. 1, pp. 58-59.

[17] Aslund 2007, p. 160.

[18] Numbers from: Stephen Crowley, “Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Russia’s Troubled Coal Industry”, in: Peter Rutland (ed.), Business and State in Contemporary Russia, Boulder: Westview Press 2001, pp. 129-149.

Follow the WSWS