I talk to friend and frequent guest Manuel Rozental about the breakdown of the (probably inaccurately named) peace process in Colombia, as FARC dissidents announce that the accords have failed and they are returning to war. We talk about war and peace in Colombian history and a global economy that profits more from war than from peace.

Category: The Americas

The Ossington Circle, Episode 33: Grounded Authority – The Algonquins of Barriere Lake Against the State, with Shiri Pasternak

I talk to Shiri Pasternak, Research Director at the Yellowhead Institute and author of Grounded Authority: The Algonquins of Barriere Lake Against the State. We cover Indigenous authority, jurisdiction, sovereignty, solidarity, and Canada’s coups d’etat in Indian Country.

Inside the neoliberal laboratory preparing for the theft of Venezuela’s economy

As we watch a US-backed coup unfold in a distant country, as in Venezuela today, our eyes are drawn to the diplomatic, military, and economic elements of the US campaign. The picture of a scowling John Bolton with a big yellow notepad with the message “5,000 troops to Colombia” reveals the diplomatic and military elements. The New York Times headline “U.S. Sanctions Are Aimed at Venezuela’s Oil. Its Citizens May Suffer First” reveals the economic element.

But US foreign policy mobilizes every available resource for regime change and for counterinsurgency. Among those resources, you will always find academics. The pen may not always be mightier than the sword, but behind every US-backed war on a foreign people there will be a body of scholarly work.

The academic laboratory of the Venezuelan coup has the highest academic pedigree of all—it’s housed at Harvard. Under the auspices of the university’s Center for International Development, the Venezuela project of the Harvard Growth Lab (there are growth labs for other countries as well, including India and Sri Lanka) is full of academic heavyweights, including Lawrence Summers (who once famously argued that Africa was underpolluted). Among the leaders of the growth lab is Ricardo Hausmann, now an adviser to Juan Guaido who has “already drafted a plan to rebuild the nation, from economy to energy.”

In an interview with Bloomberg Surveillance, Hausmann was asked who would be there to rebuild Venezuela after the coup—the IMF, the World Bank? Hausmann replied (around minute 20), “we have been in touch with all of them. … I have been working for three years on a ‘morning after’ plan for Venezuela.” The hosts interrupted him before he could get into detail, but the interview concluded that bringing back the “wonderful Venezuela of old,” for investors, would necessitate international financial support. Never mind that the “wonderful Venezuela of old” was maintained through a corrupt compact between two ruling parties (called “Punto Fijo”) and the imprisonment and torture of political opponents—amply documented but forgotten by those who accuse Maduro of the same crimes.

The Growth Lab website provides some other ideas of what Hausmann’s plan likely includes: Chavez’s literacy, health care, and food subsidy “Missions,” a growth lab paper argues, have not reduced poverty (and, implicitly, should go). Another paper argues that the underperformance of the Venezuelan oil industry was due to the country’s lack of appeal to foreign investors (hence Venezuela should implicitly be made more appealing to this all-important group). A third paper argues that “weak property rights” and the “flawed functioning of markets” are harming the business environment—no doubt strengthening property rights and getting those markets functioning again will be in the plan. If this sounds like the same kind of neoliberal prescription that devastated Latin American countries for generations and was imposed and maintained through torture and dictatorship from Chile and Brazil to Venezuela itself, that is because the motivation is to bring back the “wonderful Venezuela of old.”

A Wall Street Journal article by Bob Davis from 2005 credits Hausmann with being part of the original Washington Consensus in 1989, “the economic manifesto [that] identified government as a roadblock to prosperity, and called for dismantling trade barriers, eliminating budget deficits, selling off state-owned industries and opening Latin nations to foreign investment.” But before returning to the neoliberal prescription, Hausmann experimented with different economic ideas, including some heresies. If the WSJ article is to be believed, Hausmann looked at the data on Latin American economic growth decades later and found “Deep reforms; lousy growth,” and concluded that there “must be something wrong with the theories of growth.”

Hausmann’s academic work is highly technical, macroeconomic modeling. The models reveal the consequences of the assumptions used to construct them: at times there is some data fit to them. Others are applied mathematics exercises. A paper on 2005 “Growth Accelerations” looks for periods when countries’ economies grew quickly. An earlier paper, from 2002, presents a roundabout argument on the so-called “resource curse,” in which oil-dependent economies (like Venezuela) suffer poor developmental performance, arguing at that time that “more interventionist policies to subsidize investment in the non-tradable sector may also have a role to play.”

But whether it was written by Hausmann or not, the economic plan of Guaido’s post-coup government has no such heterodox ideas in it, however. It is difficult to imagine Hausmann or Guaido going against Bolton, who told Fox News that “It will make a big difference to the United States economically if we could have American oil companies invest in and produce the oil capabilities in Venezuela.” The post-coup Venezuelan economy will not be all about mathematically rigorous experiments in economic growth like Hausmann’s academic work. It will be about the privatization of Venezuela’s assets.

Hausmann might have a long and ideologically winding record of publishing models of economic growth, but he has maintained a passion for regime change in Venezuela for more than a decade—even at the expense of academic integrity. After the Venezuelan opposition failed to oust Chavez in a coup in 2002 and failed again to oust him using a strike of the Venezuelan oil company in 2003, they resorted to constitutional means—a recall referendum, in 2004. Voters overwhelmingly rejected the recall in the referendum, which featured then new electoral machines that did an electronic tally verified by printed ballots (still the system used in Venezuela and praised by former US president Jimmy Carter in 2012 as the “best in the world”) and was overseen by numerous international observers including the Carter Center. But Hausmann prepared a highly dubious statistical analysis to cast doubt on the outcome. Hausmann’s dubious statistics were cited numerous times. More may have been made of them had they not been thoroughly discredited by the US-based Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR). Mark Weisbrot of CEPR summarized the episode in a 2008 report:

“… the political impact of economic and econometric research on Venezuela can be very significant. For example, in 2004, economists Ricardo Hausmann of Harvard’s Kennedy School (a former Minister of Planning of Venezuela) and Roberto Rigobon of MIT published a paper purporting to show econometric evidence of electronic fraud in the 2004 presidential recall referendum. The theory of the fraud was implausible in the extreme, the statistical analysis was seriously flawed, and the election was observed and certified by the Carter Center and the Organization of American States. Nonetheless this paper had a substantial impact. Together with faked exit polls by Mark Penn’s polling firm of Penn, Schoen, and Berland—which purported to show the recall succeeding by a 60-40 margin, the mirror image of the vote count—it became one of the main pieces of evidence that convinced the Venezuelan opposition that the elections were fraudulent. On this basis they went on to boycott the 2005 congressional elections, and consequently are without representation in the National Assembly.

“The influence of this Hausmann and Rigobon study would probably have been much greater, but CEPR refuted it and then the Carter Center followed with an independent panel of statisticians that also examined these allegations and found them to be without evidence. Nonetheless, the Wall Street Journal and other, mostly Latin American publications, used the study to claim that the elections were stolen. Conspiracy theories about Venezuelan elections continue to be widely held in Venezuela, and are still promoted by prominent people in major media sources such as Newsweek, even with regard to the recent constitutional referendum of December 2, 2007.”

Hausmann’s 2004 statistical gambit is actually an established part of the US-coup playbook. The academic analysis of an election and the finding of flaws, real or imagined, in an electoral process are the beginning of an ongoing claim against the target’s democratic legitimacy. The created flaw is then repeated and emphasized. Even if it was spurious and debunked, as was Hausmann’s 2004 analysis, it can continue to perform in media campaigns against the target. After years of such repetition, the target can safely be called a “dictator” in Western media, even if the “dictator” has more electoral legitimacy than most Western politicians.

The elected president of Haiti, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, was overthrown in a US-backed coup in 2004. Haiti’s Hausmann was an academic named James Morrell. After Aristide won reelection in 2001 in a landslide, he stood poised to make major legislative moves on behalf of the country’s poor majority. Morrell published an article about how Aristide had “snatched defeat from the jaws of victory,” because of irregularities in the election of eight senators (out of 19, 18 of which were won by candidates from Aristide’s party): only the votes of the top four candidates in the senatorial elections were counted for these senate seats. These senators would have won regardless of the methodology used, but these supposed irregularities were enough to initiate the financial punishment of Aristide’s government: the suspension of Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) financing, to the tune of $150 million. All eight senators were made to vacate their seats, but the IADB never provided the loan. Morrell’s article played a key role as the intellectual backing for the attack on the Aristide government’s legitimacy, despite Aristide’s overwhelming victory in the 2001 election and the contrived nature of the “irregularities” in the senate seats.

The coup against Aristide unfolded over a period of years: economic warfare, paramilitary violence, and the eventual kidnapping of Aristide from the palace were the tactics of choice in that regime change. But the academics preceded the coup, and followed it, providing justifications and obfuscations of what was happening in the post-coup, counterinsurgency violence.

Latin American social violence has even longer-running academic underpinnings. Today, Colombia’s president, Iván Duque (the protégé of the previous warlord-president Álvaro Uribe Vélez), leads the call for regime change in Venezuela. Duque’s country was reshaped by a multigenerational civil war during which the countryside was depopulated, through paramilitary violence, of millions of peasants (many of them Afro-Colombian or Indigenous). The academic theorist behind this was the Canadian-born, US “new dealer” Lauchlin Currie, whose theory (summarized by academic James Brittain in a 2005 article), called “accelerated development,” was that “the displacement of rural populations from the countryside and their relocation to the urban industrial centers would generate agricultural growth and technological improvements for Colombia’s economy.” Currie implemented these ideas as the director of the foreign mission of the World Bank from 1950, and as adviser to successive Colombian presidents. Today Colombia continues to suffer from Currie’s academic theories. Despite the peace deal of 2016, it has the largest internally displaced population in the hemisphere.

John Maynard Keynes wrote that “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.”

As Max Blumenthal and Ben Norton show in their article about him, Guaido is just such a practical man, a US-foundation-funded street fighter for the rich neighborhoods of Caracas. But he certainly has use of the academic scribblers gathered at Harvard.

When it comes to suppressing the people of Latin America in their hopes to control their own fortunes and their own resources, the scribblers have a key role to play, as much as their diplomatic and military counterparts.

Justin Podur is a Toronto-based writer. You can find him on his website at podur.org and on Twitter @justinpodur. He teaches at York University in the Faculty of Environmental Studies.

This article was produced by Globetrotter, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Why it’s so hard for most countries to be economically independent from the West

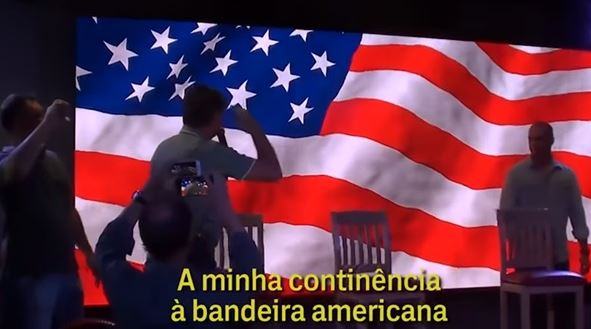

Brazil’s president Bolsonaro salutes the American flag

Why is it so difficult even for huge countries with large, diversified economies to maintain independence from the West?

If anyone could have done it, it was Brazil. In the 19th century it was imagined that Brazil could be a Colossus of the South to match the U.S., the Colossus of the North. It never panned out that way.

And 100 years later, it still hasn’t happened. With a $2 trillion GDP (a respectable $9,800 per capita), nearly 200 million people, and a strong manufacturing base (the second largest in the Americas and 28.5 percent of its GDP), Brazil is far from a tiny, weak island or peninsula dependent on a patron state to keep it afloat.

When Luiz Inacio “Lula” da Silva won a historic election to become president of Brazil in 2003, it seemed like an irreversible change in the country’s politics. Even though Lula’s Workers’ Party was accused of being communists who wanted to redistribute all of the country’s concentrated wealth, the party’s redistributive politics were in fact modest—a program to eradicate hunger in Brazil called Zero Hunger, a family-based welfare program called the Family Allowance, and an infrastructure spending program to try to create jobs. But its politics of national sovereignty were ambitious.

It was under Workers’ Party rule (under Lula and his successor, president Dilma Rousseff, who won the 2010 election to become president at the beginning of 2011) that the idea surged of a powerful BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) alliance that could challenge the ambitions of the U.S.-led West. Brazil took steps to strengthen its manufacturing, and held its ground on preventing pharmaceutical patent monopolies. Lula’s Brazil accused Western countries of hypocrisy for insisting both on “free trade” with poor countries and farm subsidies for themselves. Brazil even moved in the direction of building an independent arms industry.

Contradictions remained: The Workers’ Party government sent Brazilian troops to command the UN force that enacted the U.S.-impelled occupation of Haiti—treating the world to the spectacle of the biggest, wealthiest country in the region helping the U.S. destroy the sovereignty of the poorest as part of its foreign policy. But in those years Brazil refused to renounce its alliance with Venezuela’s even more independent-minded government under Hugo Chavez; it defended ideas of South-South cooperation, especially within Latin America, and it made space for movements like the Landless Peasants’ Movement (MST).

But after more than a decade of Workers’ Party rule, what happened? President Rousseff was overthrown in a coup in 2016. When polls showed that Lula would have won the post-coup election, he was imprisoned to prevent him from running. And so with the Workers’ Party neutralized, Brazil elected Jair Bolsonaro, a man who famously saluted the American flag and chanted “USA” while on campaign (imagine an American leader saluting the Brazilian flag during a presidential campaign). No doubt the coup and the imprisonment of Lula were the key to Bolsonaro’s rise, and failings like supporting the coup in Haiti played a role in weakening the pro-independence coalition.

But what about the economy? Are Brazil’s leaders now dragging the economy into the U.S. fold? Or did the Brazilian economy drag the country back into the fold?

Brazil’s economic history and geography have made independence a challenge. Colonial-era elites were interested in using slave labor to produce sugar and export as much of it as possible: The infrastructure of the country was built for commodity extraction. Internal connections, including roads between Brazil’s major cities, have been built only slowly and recently. The various schemes of the left-wing governments of the last decade for South-South economic integration were attempting to turn this huge ship around (not for the first time—there have been previous attempts and previous U.S.-backed coups in Brazil), and to develop the internal market and nurture domestic industries (and those of Brazil’s Latin neighbors).

Yesterday’s dependent economy was based on sugar export—today’s is based on mining extraction. When Bolsonaro was elected, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation quickly posted a story speculating on how the new government would be good for Canadian mining companies. The new Brazilian president plans to cut down huge swaths of the Amazon rainforest. Brazil is to return to its traditional role of providing natural resources to the U.S. and to the other rich countries.

A smaller country with a stronger pro-independence leadership, Venezuela faced similar structural economic problems that have imperiled and nearly derailed the independent-minded late president Hugo Chavez’s dream that Venezuelans would learn to eat arepas instead of hamburgers and play with Simon Bolivar dolls instead of Superman ones. There, too, the pro-independence project had a long-term goal of overcoming the country’s dependence on a single finite commodity (oil), diversifying its agricultural base and internal markets. And there, too, the challenge of doing so proved too great for the moment, especially in the face of an elite at least as ruthless as Brazil’s and nearly two decades of vindictive, pro regime-change U.S. policy. Today Venezuela’s “Bolivarian project” is in crisis, along with its economy and political system.

There are other sleeping giants that remain asleep, perhaps for economic reasons. In the face of relentless insults by Trump, the Mexican electorate chose a left-wing government (Mexicans have elected left-wing governments many times in the past few decades, but elections have been stolen). But locked into NAFTA, dependent on the U.S. market, Mexico also would seem to have little option but to swallow Trump’s malevolence.

Egypt is the Brazil of the Middle East. With 100 million people and a GDP of $1.4 trillion, the country that was for a few thousand years the center of civilization attempted in the 20th century to claim what is arguably its rightful place at the center of the Arab world. But today, this giant and former leader of the nonaligned movement is helping Israel and the U.S. starve and besiege the Palestinians in Gaza and helping Saudi Arabia and the U.S. starve and blockade the people of Yemen.

Egypt stopped challenging the U.S. in the 1970s after a peace deal brought it into the fold for good. Exhaustion from two wars with Israel were cited as the main cause—though a proxy war with Saudi Arabia in Yemen and several domestic factors also played a role. But here, too, is there a hidden economic story?

Egypt has oil, but its production is small—on the order of 650,000 barrels a day compared to Saudi Arabia’s 10 million barrels, or the UAE’s 2.9 million. It has a big tourist industry that brings in important foreign exchange. But for those who might dream of an independent Egypt, the country’s biggest problem is its agricultural sector: It produces millions of tons of wheat and corn, but less than half of what it needs. As told in the classic book Merchants of Grain, the politics of U.S. grain companies have quietly helped feed its power politics all over the world. Most of Egypt’s imported grain comes from the U.S. As climate change and desertification wreak havoc on the dry agricultural ecosystems of the planet, Egypt’s grain dependence is likely to get worse.

The structures of the global economy present challenges to any country or political party that wants to try to break out of U.S. hegemony. Even for countries as big and with as much potential as Brazil or Egypt, countries that have experienced waves of relative independence, the inertia of these economic structures helps send them back into old patterns of extraction and debt. In this moment of right-wing resurgence it is hard to imagine political movements arising with plans to push off the weight of the economic past. But that weight cannot be ignored.

This article was produced by Globetrotter, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

The Ossington Circle Episode 26: Free Milagro Sala! With Jorge Garcia-Orgales

I talk to Argentinian-Canadian union activist Jorge Garcia-Orgales about Milagro Sala, an Indigenous politician and activist who is currently a political prisoner of Argentina’s right-wing government.

El Circulo Ossington Episode 23: El Caso de Parex y la Extraction en Colombia desde Canada

El primer episodio del Circulo Ossington en castellano. Hable con Manuel Rozental, Oscar Sampayo, y Anna Zalik sobre la compania Parex y sus actividades de fracking en Colombia.

The Ossington Circle Episode 21: Venezuela’s Crisis with Maria Paez Victor

I talk to Maria Paez Victor of the Canadian, Latin American, and Caribbean Policy Centre and the Louis Riel Bolivarian Circle about Venezuela’s revolution, Chavismo, Maduro, the Venezuelan opposition, and the idea of the upcoming Constituent Assembly.

The Ossington Circle Episode 22: Honduras and Empire with Shipley and Coleman

I talk to Tyler Shipley, author of Ottawa and Empire: Canada and the Military Coup in Honduras, and Kevin Coleman, author of A Camera in the Garden of Eden: The Self-Forging of a Banana Republic. Both are scholars of Honduras and its relationship to the Empire, and the conversation stretches back into the 20th century and the 1954 strike, coming back to our times to focus on the 2009 coup against the elected government of Mel Zelaya and what has happened since.

The Ossington Circle Episode 20: The Great Haiti Humanitarian Aid Swindle with Timothy T Schwartz

I talk to anthropologist Timothy T Schwartz, author of The Great Haiti Humanitarian Aid Swindle (and the equally shocking Travesty in Haiti). Schwartz details the workings of the propaganda and malpractice of the charity business to which Haiti is subjected.

The Ossington Circle Episode 19: The New Cold War with Roger Annis

I speak with Roger Annis, editor of Newcoldwar.org, about Russia, imperialism, the new cold war, and the analytical challenges for leftists in the West.