Originally published by my friends at Cosmonaut:

For too long there appeared a conflict between what seemed to be eternal, to be out of time, and what was in time. We see now that there is a more subtle form of reality involving both time and eternity.

Prigogine, describing physical non-equilibrium systems.

The bud disappears when the blossom breaks through, and we might say that A building is not finished when its foundation is laid; and just as little, is the attainment of a general notion of a whole the whole itself. When we want to see an oak, we are not satisfied to be shown an acorn instead. In the same way science, the crowning glory of a spiritual world, is not found complete in its initial stages.

Hegel

I

The world is complicated and opaque. The old societies, such as hunter-gatherer tribes or agricultural communities, could comprehend themselves in a more total way than modern societies. We may understand better today the laws that rule the natural universe, laws that we have been able to manipulate to send man to space, impregnate the air with electromagnetic waves that carry instantaneous messages, and annihilate whole cities with the mass-energy of atoms. But the self-comprehension of ourselves as a society is lower than in antiquity, for today’s laws that make the community flourish are sunken below layers of complexity and abstraction. In ancient cities, like Rome, or Athens – or inclusively in the urbanization projects of many developing countries of the 20th century – the restrictions that inhibited flourishing were well known. For the destiny of communities was rooted in their capacity to create the calories and housing necessary to sustain a population, and these activities were constrained by the capacity of agriculture to create sufficient flows of energy.

Today, our bodies and spirits are subject to many complex and contradictory forces, that sometimes lead to tidal waves that submerge our destinies beneath emergent properties of which we have very little control or understanding. Even the economic elites, with their capital and firms, only have partial epistemological access to the chain reactions that their activities can unleash. These actions can lead to financial chaos, the elite’s capital devaluation, or mediatic crisis. Another complexity nexus is how our biological bodies react before the abstract layers and terraforming created by the capitalist world-system. We are evolved animals, produced by natural selection, but we are also abstract animals programmed by the semi-autonomous systems created by modern civilization, including its landscapes of concrete, glass, and steel. Trying to grasp the specific mechanisms that mould the human spirit is a very complex task.

In other words, we human beings are subject to microphysical mechanisms, constrained by particularities like “free” choices and biological processes, but we are also regulated by macroscopic forces that are universal and abstract, such as financial systems, history, culture, and the market. This dialectic of the particular and universal cannot be dissected surgically, for the microphysical and macrophysical aspects are in communication with each other, generating an interrelation that is not easy to disassemble.

The cosmos is living and palpitating, in constant flux. For example, the worlds of the hunter-gatherer and the 21st-century cybernetic-worker are entirely different universes, even if there are similarities rooted in the human being’s evolved animality. However, today’s self-mythology of modernity is based on inert and linear laws. This is due to the victory of the technique, which had triumphed in the 19th and 20th century. Chemistry, electromagnetism, and nuclear physics could be manipulated to create a world filled with light, machines, and mechanical monsters that devour human bodies. This capacity of the technique to convert a forest into a storehouse of energy created a class of enthusiastic intellectuals that wanted to apply it to every class of problems. In other words, they wanted to violently convert the universe into a mechanical clock.

In all disciplines, inclusively in those not related to the natural sciences, this tendency towards the technique can be seen in the dissection of a substance into its analytic parts. However, the properties of the natural sciences are different from those of the human body and its mind. In the case of the systems of natural sciences, the problems studied are linear and static. Linear in the sense that the system can be approximated as the sum of its parts. For example, in many calculations involving elementary particles such as electrons or photons, the system can be approximated as the sum of its parts, and this makes possible a very precise mathematical study. Since many systems that are studied in the natural sciences can be approximated in this manner, the technique, that method that dissects the substance into digestible units, proved enormously useful in the investigation of the natural universe. However, the social world is an accumulation of interrelations, emergent properties, and totalities, and cannot be approximated as the sum of its parts (a linear system). In other words, the human totality is an assemblage of biological, historic, and economic processes, and cannot be disassembled that easily.

However, given the predominance of the technique, many intellectuals, scientists, and opinion makers have enthusiastically pushed it as a method to study the bio-historical-geographical assemblage that is society, trying to linearize the problem as if we were just a cumulus of electrons and quarks in steady-state, without taking into account the nonlinear, emergent properties and feedbacks. This tendency towards linear equilibrium not only is fundamentally naive but also encourages very conservative and reactionary thinking. Indeed, if this world can be explained as a product of unchanging, static universalism, then the impulse to change it for a freer and more dignified cosmos becomes an affront to science itself. Since I think this approach is not only fundamentally wrong but also imposes unfreedom – as the heart is merely reduced to electrons, springs, and wheels – I find that it is my duty to combat this cretinization. Furthermore, I also noticed that there is a tendency in both thought and activism to challenge this linear thought by pretending the world is just flux and difference, dismissing universal patterns and properties.

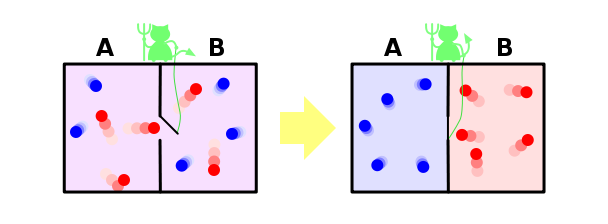

Curiously, I learned that our world is pulsating with life, light and change from science itself, as my doctorate in physics ultimately concerned the fate of nonlinear systems. A nonlinear system is ultimately a coupling of both the universal and particular. At the microscopic level, there is indeed difference and particularity, such as the random motion of particles, but this apparent individuality gives rise to macroscopic phenomena, that in turn influence the trajectory of these microscopic world-lines. Nonlinear thought tries to grasp the coupling of both the particular and universal, for a non-linear system is more than the sum of its parts, yet the behavior and properties of each individual part become relevant too. Therefore, this article is concerned with a study of the origins of this reductionist impulse to either reduce the world to the universal, or in the opposite case, the particular, and how a living and nonlinear thought should, in turn, supersede this impulse.

II

In philosophy, the technique emerged in the form of analytic philosophy in the Germanic countries, where the old form of philosophizing, which was impregnated with historicity, literature, and forests of concepts, was replaced by a philosophical program that wanted to reduce the world into logical atoms. Although the seed of this philosophical technique can be found in the work of Descartes, for in his “Discourse of Method” he explicitly describes the method of reducing a system into its atomic parts so that it can be analyzed (the geometric method), this seed did not become totalizing until the 20th century.

This assault against traditional philosophy began with the criticisms against Hegel and Heidegger launched by English and German philosophers. In England, Russell rebelled against the Hegelian-inspired idealism that was popular in that era, to replace it with a research program that exchanged the ambiguous language of traditional philosophy with logical precision. This logical-mathematical language was inherited from Frege, a mathematician-philosopher from the 19th century whose project was to reduce arithmetic to a logically consistent system that could be derived from axioms. In Germany, Carnap severely criticized the language of Heidegger, for Carnap thought the utterances of Heidegger lacked sense and were misuses of language that could indicate the emotional state of the utterer but not describe the world. These positivist philosophers wanted to reduce the world to logical and atomistic propositions that could be verified with empirical observations.

The project of logical-atomism that emerged in the early 20th century is considered a failure by philosophical consensus, but its technical spirit persists in that impulse to reduce the world to thought experiments on a canvas emptied of history. For example, one of the most famous analytic philosophers of the second half of the 20th century, John Rawls, developed a theory of justice where the initial assumption of his thought experiment was a “veil of ignorance” where the citizen has no knowledge of their social, cultural, and psychological position in relation to other members of society. I will not affirm that Rawls’s methods cannot be useful in specific contexts, but it still demonstrated that tendency to linearize the world into a thought experiment, ignoring the nonlinearities of history. Given that the political world is nonlinear, and is more than the sum of its parts, the true materialist dialectic must grasp the interactions between the abstractions of history and the particularities of individuals, not just reduce the problem to a geometric derivation.

III

Another example of thought infected by linear technique is economics. The political economy of the 19th century, which studied the couplings between social classes, and the value and labor chains that began in agriculture and ended in factories, has been marginalized to the remote wing of only a few university departments. Today, the economy focuses on mathematical functions of utility that are maximized in order to calculate agent preferences and Walrasian equilibrium. In other words, the destiny of mankind, with all its historical, institutional and cultural dimensions, is reduced to mathematical functions, equilibrium and stationary state assumptions.

These assumptions exist because they linearize the problem, approximating it into something similar to those systems that are already well understood in the natural sciences. However, these assumptions that treat the economy as a linear problem end up converting the abstract mathematical model into a concrete policy objective, especially after the economic shock of the 70s. In other words, Washington tried to submit the rich and nonlinear complexity of developing countries to the violence of a myopic universality. For example, the policies of developing countries focused on the liberalization of the market due to models of Walrasian equilibrium that were in fashion in that era. The state intervention that was ubiquitous in developing economies, including such policies as fiscal expansion and import-substitution, was criticized for distorting the market, and therefore triggering scarcities of commodities.1 Anglo-Saxon economists counseled Latin American countries to liberalize their economies, pointing at the economic growth experienced by some countries in Eastern Asia (e.g. Singapore, South Korea, China).

This linear and abstract thinking wishes to submit the chaotic world to the violence of universality, yet, it was unable to capture the historicity of developing countries, which goes beyond tepid Walrasian equilibrium. The economic liberalization of Latin America did not birth the economic growth that was expected, but caused contractions, inequality, and slow growth.2 A more materialist analysis of Asian economies would reveal that the liberalization narratives of those Western economists were simply a caricature. In all of those Asiatic countries, the government intervened in an extreme manner that countered the counsel of Washington, to the point that such intervention contradicted Anglo-Saxon economic orthodoxy. According to the models of Washington, governmental presence of such magnitude would lead to great distortions of the market, producing inefficiencies and scarcities. However, these Asian countries instead experienced great economic development thanks to state planning.

An example of the misjudgments of these economists is the case of South Korea. While the marginalists argued that South Korea experienced an explosive economic growth thanks to market liberation, more accurate studies found that the state had great control of the most important industries.3 Even if the state did not possess these industries in a legalistic and transparent manner (the only manner intelligible to Anglo-Saxon brains with their myopia of formal structures), the state manipulated them for the accomplishment of discrete and planned objectives. A great part of this planning was possible because the state controlled the financial system and could manipulate corporate incentives through discretional credits.4 In fact, some economists saw the relation of the state to firms as forming one organization, where firms were simply internal organs of a corporate association between them and government.

Other Asian examples demonstrate even more the deficiencies of Western orthodoxy. For example, all the economists that see the growth of China as evidence of the supremacy of the free market are blinded by their fidelity to Anglo-Saxon abstractions. Other more nuanced thinkers have argued that the current growth of China is rooted in the base of the “socialist” state imposed in the 50s, when China adopted the Stalinist model, since this was an era where a rational state capable of organizing society under a unitary plan was erected.5 Today, the plan of the Chinese Communist Party is to be open to the global market, but this process is imposed through planning that is possible due to the Stalinist base of the state.6 Furthermore, a great part of capital-intensive industry is still controlled by the state.

Finally, the experience of the USSR can be seen as a refutation of many of the precepts of marginalism. The USSR did suffer from inefficiencies and scarcities, and thus it could be said that it did not obtain the Walrasian equilibrium between supply and demand, but even then the country industrialized extremely quickly, destroying illiteracy, unemployment and turning into an industrial power. Finally, a great part of this growth happened when the majority of the capitalist world was sunken into a depression.

I do not want to justify the experiences of Asiatic countries and the USSR as examples that must be followed, I simply seek to show how myopic and incorrect economic orthodoxy is. Given its violent abstractions, it was incapable of grasping the roles of culture, state, and economy that a genuinely materialist and dynamic thought comprehends. Given these concrete nonlinearities, the counsel of Washington’s economists led many developing countries to inequality, economic contraction, and slow growth. The Anglo-Saxon technocrat linearized concrete reality in the economic periphery through coercion and the spillage of blood, in the form of military dictatorships and economic blockades.

IV

Until now, I have only focused on the linearity of philosophy and the social sciences. However, the same reductionist impulse can be found in some corners of psychology and genetics. This tendency is to reduce the destiny of mankind to microscopic variables – specifically biological ones – a tendency manifests itself at various levels of intensity. In the field of behavioral genetics, there exists a legitimate scientific debate (erroneous, in my opinion, which I will explain later) about what is nature versus nurture. For example, there is a consensus that our psychology and behavior is partially inherited, where inheritance explains about thirty to fifty percent of our behavior.7 Yet, inherited variables do not necessarily have a biological origin, for example, cultural aspects can also be inherited. As a matter of fact, the most advanced techniques of behavioral genetics, such as thestatistical correlation of clusters of genes to intelligence, only find correlations of five to ten percent.8

Therefore, these studies have only been able to demonstrate a correlation with a percentage that, in the best of cases, is of fifty percent, but without being able to show that these inherited variables have biological origin. This limitation has not stopped scientists like Robert Plomin of proclaiming that our behavior is determined mostly by our biology, and that neither therapy nor environment can change this fact.9 A related argument is the divergence of behavior between different sexes, for example, the paucity of women in the mathematical sciences, that some psychologists correlate with biological variables.10

In a milieu outside scientific legitimacy, there exist extremists that give a radical and macro-economic twist to these statistical correlations. I have analyzed this style of argument in a previous article.11 Basically, the most extreme versions of this perspective try to explain socio-economic divergences between the core and periphery as a function of pseudo-biological variables such as intellectual quotient. These thinkers also blame poverty of certain demographics on genetics, arguing that certain races are less intelligent than others. These viewpoints are not orthodox and only exist in the internet periphery, or are uttered by a few scientists that aren’t accepted entirely in the community of scientific legitimacy.

Rather than arguing against these extremist-racists, which I have done in a previous article, I want to return to the debate of nature versus nurture.12 In my opinion, to grasp the problem as one of biological inheritance versus environmental attributes is an inadequate scheme. The human being is integrated in a nonlinear manner to its environment, where the biological parameters interact with the social and material geography of the world, influencing each other mutually, so that disentangling the interaction into isolated poles is probably impossible.

A contemporary advance that demonstrates these nonlinearities is epigenetics, where environmental parameters determine which parts of the genetic code express themselves phenotypically, and these epigenetic modifications can be inherited even when in theory they do not change the DNA. For example, research has shown that stressful environments can impose epigenetic modifications on an organism.13

Some psychologists have begun to understand that the scheme of nature versus nurture is erroneous. For example, scientists in the field of child development have sketched how genetic and epigenetic factors interact with early childhood experience, and how this interaction leads to the structuring of neural connections and moulds the manner in which complex and mental activity is effectuated. In other words, these scientists developed a nonlinear theory of childhood development as a function where both biology and environment are coupled.14

In conclusion, in the same way orthodox economists cannot grasp the world system as a dynamic organism filled with historicity, for they submit it to dead and steady-state laws, those who try to explain the destiny of the human being as a simple function of biological parameters do not grasp the nonlinearities of Homo sapiens as a being embedded within its historical-geographic surroundings. In other words, these thinkers entertain false and vulgar materialism. A sophisticated materialism would grasp how the biological processes are interrelated with the environment, influencing each other. Nafis Hasan described these limits of biological determinism and presented dialectical materialism as a method of understanding nonlinearities.15

V

While the technicians have erred in abstracting the world under universalism, there are those who oppose this abstract realm by enshrining the particular and different. For example, activist and intellectual movements of the Left celebrate the microphysical and particular to oppose the centralization of capital and the American empire. In this type of thought, macrophysical properties that emerge from microphysical processes, and at the same time mould and constrain the microphysical, are not taken into account. In the case that these macrophysical-universal processes are considered, they are perceived as obstacles to freedom, and therefore, fragmenting them becomes imperative. This fetishization of the particular emerges in pure thought and also in political activism. Its origins can be pinpointed to the continental philosophy of the 20th century. Heidegger, at the beginning of the 20th century, rebelled against the abstract and calculating thought of the West in order to push forward a philosophy that emphasized intuition, the immediate environment, and the particular culture.

The great abstraction of the West, the desire to catalogue and describe entities in a systematic manner, was seen by Heidegger as an obstacle which prevented the disclosing of Being in a more holistic and immediate sense. Instead of tapping into truth through speculative-abstract thought, Heidegger saw the authentic being as rooted in the destiny of blood and soil – in the existential confrontation before Death.

Heidegger’s students informed the French philosophy of the second half of the 20th century. In the world of French post-structuralism, logical meshes did not constrain entities, but entities existed in a universe of fluxes, multiplicities, and difference. These processes in flux could only be investigated at the local level since, according to these philosophers, theory became unintelligible and unstable at the global level. For Foucault, local networks of power constrained knowledge. Derrida considered all conceptual infrastructure, such as science or Marxism, to be unstable. The universe of Deleuze was one of fluxes of energy, matter and signs, where unstable nodes could exist, but not universal laws.

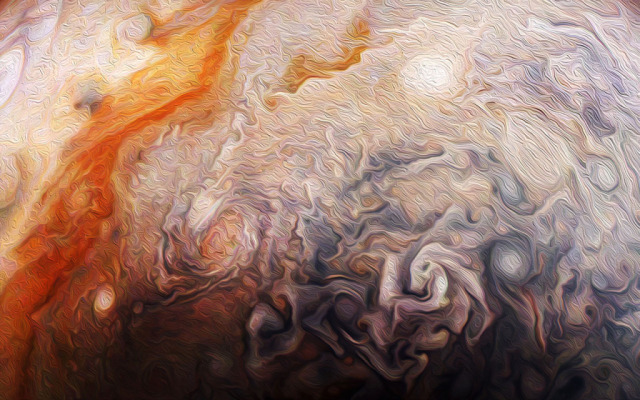

However, the materialist, informed by natural sciences, knows that the laws that rule the universe are interconnected across various scales, and that macroscopic scales influence the microscopic scales and vice versa. For example, gravity, which distorts space and time, regulates cosmic scales, creating cobwebs of stars and light. In these cobwebs, spherical bodies of gas and rock pulsate, their perfectly round forms a function of the radial symmetry of gravitational force. However, the radius, temperature, and mass of these stars, planets or compact objects are caused by atomic processes that interact with gravity, such as the nuclear force between protons and neutrons, or the concentration of electrons. In this cosmic dance, the microscopic laws of quantum mechanics, and the macroscopic laws of gravity are in communication, influencing each other mutually. An authentic materialist assumes that humanity, including its collective spirit, is an emergent property of elementary particles such as quark and gluon fields, but at the same time, the social abstractions and material geographies created by mankind, such as the economy, urban spaces, and history, constrain the flux of these elementary particles. In summary, war, waged by Homo sapiens, develops the nuclear bomb that turns human bodies into vaporized carbon. Modern capitalism, that accumulation of human actions, emits photons and electrons that unite the whole world in a network of finance and communication.

This local thought also informs today’s politics. On the left, particularism manifests as the destruction of universal programmatism, like that embodied by the parties of the Second and Third International. Instead of internationalism and the struggle for the universal and socialist republic, localism, nationalism and fragmentary struggles are fetishized. An example of this phenomenon has been the European left, which sees the struggle against neoliberalism as manifested in secession from the European Union and in the affirmation of national sovereignty.

With liberals in the United States, sometimes this thought process manifests itself as the glorification of small businesses, the movement of organic farming, and the irrationalism against scientific medicine.

This reaction against universalism is understandable from a left perspective, for the bloody history of modernity is tied to empires that violated and pillaged the world with “enlightened” pretensions. Yet, materialist thought grasps that national sovereignty is illusory, for there exists a world economic system that traverses the borders of nation-states, and even if these states have the capacity to manipulate some endogenous variables in their territory, the destiny of these national economies is controlled by the tidal waves of the world-system, and the long and slow historicity that drags the corpses of dead generations. Given this reality, it is necessary to struggle against the world-system not only in a local and fractal manner but also with the creation of a global, sovereign machine that can channel the world-system for the benefit of all. In other words, it’s necessary to establish a worldwide socialist republic.

VI

Not only is linear thought incompatible with the truth of a palpitating and living universe, but it cannot imagine a world of a flourishing humanity, for linear thought considers the current dark state in equilibrium and eternal. This attitude inhibits the march toward the splendid city that will give light, dignity, and justice to all human beings (Neruda). We not only require an infinite patience for the future dawn, but also a deep comprehension of the nightmare of the past. Yet, technical barbarism conceals the weight of the past generations, for it sees the human being as an individual agent surrounded by a canvas emptied of history and geography. This tendency will always end in reaction, for the laws of its world are inert and, therefore, fundamentally conservative.

To be a radical is to be a non-linear thinker. The problems of the present are embedded in a complex system, for the historical and economic laws that regulate this world are the same laws that cause global warming and financial crisis. Therefore, a radical and socialist solution requires a total program that transforms the nexuses that connect the present calamities. Furthermore, the socialist knows that the present world system is dynamical, with only a couple of centuries of existence, for in a more remote past, coinage, the waged worker, and the commodity were not totalizing. Ironically, treating a system as nonlinear, opaque, and dynamic, converts its destiny into something transparent, capable of being channeled for the benefit of collective flourishing. In contrast, those barbaric intellectuals that theorize capitalism as something transparent and eternal, with genes and hormones as the machinery of this spurious destiny, chain humanity to the domination of elites and venal interests.

- Bruton, H. J. (1998). A reconsideration of import substitution. Journal of economic literature, 36(2), 903-936.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Lee, C. H. (1992). The government, financial system, and large private enterprises in the economic development of South Korea. World Development, 20(2), 187-197.

- Aglietta, M., & Bai, G. (2012). China’s development: Capitalism and empire. Routledge.

- Ibid.

- Plomin, R., & von Stumm, S. (2018). The new genetics of intelligence. Nature Reviews Genetics, 19(3), 148.

- Ibid.

- https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/in-the-nature-nurture-war-nature-wins/

- Schmitt, D. P., Realo, A., Voracek, M., & Allik, J. (2008). Why can’t a man be more like a woman? Sex differences in Big Five personality traits across 55 cultures. Journal of personality and social psychology, 94(1), 168.

- https://colddarkstars.wordpress.com/2017/09/01/the-univariate-mind-of-the-far-right-crank/

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- https://cosmonaut.blog/2019/01/01/eugenics-2-0-how-dialectical-materialism-can-end-the-nature-vs-nurture-debate/

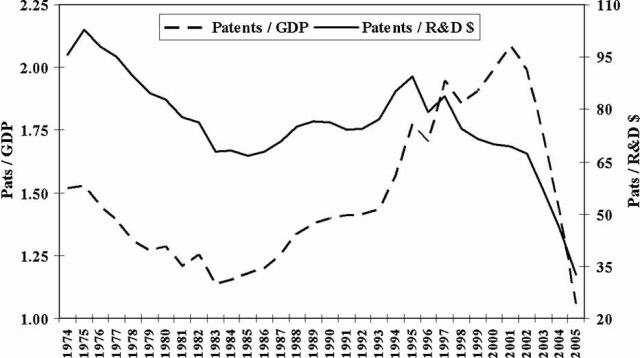

Source: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/wp22_baily-montalbano_final4.pdf

Source: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/wp22_baily-montalbano_final4.pdf Source:

Source:  Source: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/sres.1057

Source: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/sres.1057

Source: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/cross-check/is-science-hitting-a-wall-part-1/

Source: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/cross-check/is-science-hitting-a-wall-part-1/