Images

The Delicate Art of Getting It: Comics as a Tool for Unpacking Privilege

“Black and Third World people are expected to educate white people as to our humanity. Women are expected to educate men. Lesbians and gay men are expected to educate the heterosexual world. The oppressors maintain their position and evade their responsibility for their own actions. There is a constant drain of energy which might be better used in redefining ourselves and devising realistic scenarios for altering the present and constructing the future.”

How many times has some variation on this theme been thrown in the face of some well-intentioned person? They’re “just trying to understand”, and how can they do so if you won’t explain? As an upper middle class white dude, I remember asking such innocent-seeming questions myself, failing to appreciate what the Audre Lorde quote above explains: educating your oppressor is draining! I was lucky enough to have a kind and very patient friend to deliver a staggering series of savage defeats in debates I had imagined I’d won. It took years for the implications of her arguments to penetrate the murky sludge of privilege and teach me an essential lesson: it can be hard to understand what we do not experience. The experience of oppressed people and our difficulty in understanding it makes them an other, separate from us and outside our understanding.

For those unfamiliar with this academic term, the “other” describes the relationship of those excluded or oppressed by a group or society by virtue of their identity. You know what they say where clarity’s concerned: “a .jpg is worth a blog post but a meme will do in a pinch.” So there’s a kind of emotional truth to the expressions of the otters linked above that we wouldn’t get from a graduate course on the subject. The appeal of a snarling otter over the excruciating tedium of a dozen French philosophers is obvious. This otter is asks us to go beyond feeling bad about our privilege and understand it is disgusted with our failure to do anything about it – or maybe just disliked that chewed up watermelon.

For those unfamiliar with this academic term, the “other” describes the relationship of those excluded or oppressed by a group or society by virtue of their identity. You know what they say where clarity’s concerned: “a .jpg is worth a blog post but a meme will do in a pinch.” So there’s a kind of emotional truth to the expressions of the otters linked above that we wouldn’t get from a graduate course on the subject. The appeal of a snarling otter over the excruciating tedium of a dozen French philosophers is obvious. This otter is asks us to go beyond feeling bad about our privilege and understand it is disgusted with our failure to do anything about it – or maybe just disliked that chewed up watermelon.

But otters keep a busy schedule and can’t be everywhere! Luckily, there are comics. The internet has helped broadcast the voices of the oppressed to a wider audience than was previously possible. People who would struggle to get a speaking role on a third-string sitcom can have audiences in the hundreds of thousands, and comics are one of the most accessible media to do so. For regular people struggling to understand how their privilege can be harmful to otters, comics beat the heat of the librarian’s stare when your intellectual sweat starts to stain the aging furniture your local bibliotheque.

Comics can be an excellent way to visually represent concepts that take ages to present in text. That’s 500 years of exploitation in six panels, and if it lacks the nuance of a textbook on the triangular trade, hey, it’s a starting point. An interested person with good intentions can proceed from here to Google, Wikipedia or the nearest library. It is the beginning of a frame of reference. Most importantly, it conveys an emotional truth.

So much of oppression hinges on emotional truth. One can produce endless statistics on mortality rates during Atlantic crossings, the value generated by slaves for the American economy, the value of unpaid housework to the capitalist economy or whatever else suits you. But notwithstanding statistical significance, you know what they say: tell a human story, people can relate. If you want to bore them, use statistics.

While there might be a startling brutality to statistics on trans suicides, many may find it easier to relate the above comic to their own experience of breaking difficult news to their parents. It is always the case when unpacking your privilege that a dash of empathy goes a long way, and if the personal is political it’s electrical too. So comics are a place to plug in, and that’s always good. They can be especially effective when someone who shares your privilege uses comics as a way to speak directly to your experience, and acknowledges the frustration of being called out while you are trying to educate yourself. If this comes with two scoops of tough love, at least you can see yourself in the face of the person behind the pencil.

Nothing, of course, is universal. But the beauty of comics are their incredible diversity. Not every comic will illuminate every question. Seeking understanding is catching fish with your bare hands, slippery at the best of times, without mediating that search through art. For those of us hoping to improve our allyship, it is alright to admit that we just don’t get it. Sometimes, we may have no reaction to a given comic at all.

And that’s ok. In our journey to understand the differences that separate us, and the way our behaviour has the capacity to harm people, we do not need to instantly grasp every concept that’s presented. Some questions have answers you can’t put in comics, or books for that matter. Ultimately these are questions rooted in human experience and therefore best addressed through human interaction. Still, if you want to avoid putting your foot in your mouth and potentially hurting someone’s feelings, comics can be a great place to start. You never know whose life you might make a little easier.

Ad Astra Comix is building an index of comics to help prospective allies educate themselves! In the meantime, check out some of web comics linked here with permission from the artists–or e-mail us if you think there’s a particularly crucial comic to have on the list! If the comic in question comes in print, we may be interested in ordering it, so feel free to contact us about that, too. 🙂

Hasta la Victoria… ! Spain Rodriguez Wins the Battle with “CHE: a graphic biography”

Title: CHE: a graphic biography

Title: CHE: a graphic biography

Author and Artist: Spain Rodriguez

Published: 2008 (Verso Books)

Editor: Paul Buhle (also contributed an afterword on Che, co-written with Sarah Seidman)

As something of a legend in his own right, comics maker Spain Rodriguez had this Graphic Biography of Che Guevera out before the three others I have reviewed here. I wish he were still alive today, because I’d love to ask him what compelled him personally to do this piece—and furthermore, why a bunch of other people got interested in similar projects right around the same time.

Of all of the books, his has a decidedly indie style (that’s Spain for you). It was also the only work that was by a single person, not a team of writer-and-illustrator. What his visuals lack for in polish, they make up for in detail. On page 39 it shows Che getting grazed in the neck during the early days of the July 26 Movement. Nothing more is said of his wound, but there’s still a bandage on his neck by page 40, several panels later. Call me a freak but I appreciate that.

The content of the text is also excellent. Spain’s points of interest are focused, relevant, and well-argued where arguable. He goes beyond just rhetoric in quoting Che, choosing instead soundbites that let you hear the gears turning in this remarkable man’s head. This is the first book to touch on the factional disputes and internal dynamics of the July 26th Movement and the Cuban Revolution as a whole, which means that Spain believed what I believe: you can’t understand Ernesto Guevara without understanding the Cuban Revolution. If this seems too ideological, too political, well,… Try reading a biography of Thomas Jefferson without coming across the line, “We the People…” .

His narrative of the Bay of Pigs / Playa Giron is amazing—a really great piece of comic art. Great flow; not too text-heavy; educational; beautiful. There’s even a rare moment that Rodriguez is able to place himself in the story, to explain where he was and how he was feeling during the Cuban Missile Crisis. It was his generation’s take on my “Where were you on September 11th?” and I find it intriguing.

In my opinion, Spain’s Graphic Biography is the victor of this 3 week Battle of the Graphic Biographies. In all fairness, he had quite a head-start on the others. Aside from literally being the first published (which is irrelevant) he was a rebel and a leftist, a history buff, and among comic artists one of the best in illustrating the technical, from machines to military campaigns. And not to put too fine a point on it, but of all the creators involved, I don’t see evidence of anyone else having a longer relationship of admiration for Guevara. He probably had much longer to think his book through—it wasn’t just something that popped into his head after he watched The Motorcycle Dairies.

In my opinion, Spain’s Graphic Biography is the victor of this 3 week Battle of the Graphic Biographies. In all fairness, he had quite a head-start on the others. Aside from literally being the first published (which is irrelevant) he was a rebel and a leftist, a history buff, and among comic artists one of the best in illustrating the technical, from machines to military campaigns. And not to put too fine a point on it, but of all the creators involved, I don’t see evidence of anyone else having a longer relationship of admiration for Guevara. He probably had much longer to think his book through—it wasn’t just something that popped into his head after he watched The Motorcycle Dairies.

Star Rating: 4 ½ stars. Great work of political comic art.

Saturday, February 16

I haven’t read a book in Spanish in a long time… and I’ve never read a comic book, which has its own kinds of boundaries and flavours of language. Even when Spanish felt more or less as my proficient second language, jokes, double entendres and other palabra-play were never easy for me. I can count on one hand the number of punchlines I ever understood.

And so I kept stalling on this book, ¡Libertad! Because I can plainly see more and more, as I slowly crawl through these pages, that there is creativity here, and dedicated research–and passion for the story.

Title: ¡Libertad!

Author: Marise and Jean-François Charles

Artist: Olivier Wozniak, Benoît Bekaert

Published by: Ediciones Kraken, 2009 (Spanish version only – first published in French)

This book begins where most stories of Che end– his assassination at the hands of the CIA and Bolivian military and government officials.

“They say a man’s life flashes before his eyes before he goes,” the introduction reads, explaining that this is what this short comic is aspiring to do–what else could a comic book offer of a man whose impact on history was greater than many statesmen twice his age? It is for this reason that I like the format of this comic most, of all those that I have read. It is creative, yet reasonable.

Scenes jump from miltestone to milestone, as one would expect in an abridged biographical story. It begins in 1953, when Che is in Bolivia, slowly en route to Guatamala to work as a doctor, hopefully to participate in the modest reforms of President Jacobo Arbenz. He finds the woman who will become his first wife, but struggles to find meaningful work (the medical graduate complains about selling religious trinkets in the street before a car bomb explodes outside their apartment–to which his girlfriend, Hilda notes that they “may need a doctor now.”Guatemala is also where he meets members of the July 26th Movement, so it is his stage entrance into the Cuban Revolution. Scenes are taken from what we know, what is written of, the many meaningful points in Che’s life–points that tell us something of his character and capacity for leadership. This includes scenes like that of Che grilling the Cuban guerrillas who began firing on a peasant who had taken them by surprise (“What the fuck are you doing?” he says, “The land he tills isn’t even his–it’s for these people that we’re fighting!”). The book is showing, very efficiently, how “El Commandante” the man was built. Because Spanish is my second language, it’s impossible for me to tell the exact quality of the dialogue, here, but my literal translations remind me of a decent historical fiction film.

Scenes jump from miltestone to milestone, as one would expect in an abridged biographical story. It begins in 1953, when Che is in Bolivia, slowly en route to Guatamala to work as a doctor, hopefully to participate in the modest reforms of President Jacobo Arbenz. He finds the woman who will become his first wife, but struggles to find meaningful work (the medical graduate complains about selling religious trinkets in the street before a car bomb explodes outside their apartment–to which his girlfriend, Hilda notes that they “may need a doctor now.”Guatemala is also where he meets members of the July 26th Movement, so it is his stage entrance into the Cuban Revolution. Scenes are taken from what we know, what is written of, the many meaningful points in Che’s life–points that tell us something of his character and capacity for leadership. This includes scenes like that of Che grilling the Cuban guerrillas who began firing on a peasant who had taken them by surprise (“What the fuck are you doing?” he says, “The land he tills isn’t even his–it’s for these people that we’re fighting!”). The book is showing, very efficiently, how “El Commandante” the man was built. Because Spanish is my second language, it’s impossible for me to tell the exact quality of the dialogue, here, but my literal translations remind me of a decent historical fiction film.

Because the comic isn’t a documentary/biography style, with an outside narrator, I for one feel more submerged in the characters being presented: Che, Hilda, Fidel, and the minor characters that are there for pivotal moments: the Cuban who speaks with him on his way to Guatemala (in the book, he is presented as the first man to call Ernesto by the nickname “Che”), and on to the soldier who tends his wounds as he’s waiting to be killed.

Because the comic isn’t a documentary/biography style, with an outside narrator, I for one feel more submerged in the characters being presented: Che, Hilda, Fidel, and the minor characters that are there for pivotal moments: the Cuban who speaks with him on his way to Guatemala (in the book, he is presented as the first man to call Ernesto by the nickname “Che”), and on to the soldier who tends his wounds as he’s waiting to be killed.

The artwork is a very Tintin style, in my opinion, more common with European comics. I like the wash coloring–so much better than the digital colour randomness in the first book I reviewed. The illustrations aren’t stunning, but they’re certainly not bad, either. And there are a few compositions in the mix that give me the impression that the artist and author understood what was important to emphasize. For example, there is the rally in Havana Square at the dawn of the Cuban Revolution– you can literally count the frames of thousands of tiny Cuban people. If you see pictures, you’ll see that the magic of the moment in history was as much the masses as it was the words being spoken from the stage.

Despite the many positives of this book (especially when I compare it to other Che biographies), this work will reach few in North America. Because of its non-availability in English, and furthermore its large format, which makes it seem like a kids book) most of the comics readers I know would pronounce ¡Libertad! a lost cause before they even opened it. Where Sid Jacobson’s Che biography gets a 10 for accessibility, this book gets a 2. Very unfortunate, since the verdict on the books’ contents is, for me, the opposite.

Despite the many positives of this book (especially when I compare it to other Che biographies), this work will reach few in North America. Because of its non-availability in English, and furthermore its large format, which makes it seem like a kids book) most of the comics readers I know would pronounce ¡Libertad! a lost cause before they even opened it. Where Sid Jacobson’s Che biography gets a 10 for accessibility, this book gets a 2. Very unfortunate, since the verdict on the books’ contents is, for me, the opposite.

Rating: 4 stars. Some great biographical storytelling!

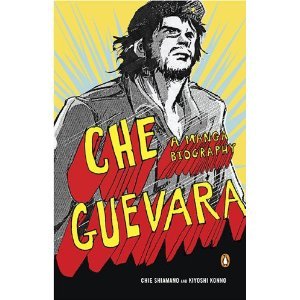

This week I’m reviewing CHE: A Manga Biography by Chie Shimano and Kiyoshi Konno, published in 2008 by Penguin Books

This week I’m reviewing CHE: A Manga Biography by Chie Shimano and Kiyoshi Konno, published in 2008 by Penguin Books

The last Che Bio I reviewed, I referred a few times to “historical inaccuracies”. In light of this Che comic, I’d like to re-characterize that distinction as “historical bias”. After all, history is open to interpretation, and there can be several “truths” welcome in a story where conflicting interests are concerned. Perhaps my beef with the book was that it was so totally American in its bias. For example, the section on the Bay of Pigs was through the eyes of a Cold-War-stricken Kennedy, not through the millions of Cubans having their country invaded (and taken advantage of by the USSR).

In my opinion, this Che biography shows an impression of Che through other eyes in the world. Like most Manga, this book comes from Japan, and approaches Che more as a folk hero than a strictly historical figure. Like most folklore, it is a light introduction to a subject–a simplified, more-or-less linear narrative.

…But before I jump into that, it has occurred to me that I never explained my rating system. When I’m reading a political comic, I’m looking for political and historical relevance, excellent research, storytelling capacity, and overall aesthetics (layout, the relationship between words and graphics). Each star, for me, represents one of these things in a five-star points system, and most works begin with one star just for bringing a political comic book into the world.

It always kills me when I see a book released by a major publisher (Penguin, in this case) where there is a typo on the first bloody page. Where the book is originally published is irrelevant; typos in an English translation are inexcusable on a 200 page book with a list price of $20.

I also find myself wondering how much of this book would make sense if I hadn’t already experienced other Che-related movies and books. There seems to be a lot of recycling here from Motorcycle Diaries. If it’s not original, at least the book is still passionate. Sid Jacobson’s CHE: A Graphic Biography (which I reviewed last week- listed below) seemed so sterile and uninspired, I wondered why or how the man got involved in writing the book.

Chie Shimano’s personal admiration for Che Guevera becomes clear about half-way through the book, as Che (now a Cuban diplomat) is traveling around the world seeking purchasers for Cuban sugar. In a last-minute itinerary change that threw his entourage into a panic, Che decided to visit the city of Hiroshima, site of the notorious U.S. bomb drop in WWII. Of everything in the book, I found this to be a high-point in the storytelling: it reveals something about both author and subject–and a connection, a passion for humanity against injustice, that they both share.

Despite this, and much stronger wording of the U.S. relationship towards Latin America (other Che biographies take note: we know you’re trying to be “unbiased”, but you can only use the words “meddling” and “intervention” so many times. Call a spade a spade: the word is “imperialism”), there remains some unfortunate truths about this book. Mangas are now prized around the world for their accessibility and entertainment value; maybe I’m expecting too much, but the dialogue here is so terrible. So scripted and campy. Again… I am reminded that this book is made with a nod to folklore–not just academic history.

There is a bibliography, but several passages that I believe required annotation, like a poem written to the passage of the Granma ship through the Caribbean, are not clearly noted.

CHE: A Manga Biography offers some original nuggets of innovation to what has become a collective storytelling of Che’s life. As well, it rightly contrasts with other more Amero-centric biographies, like Sid Jacobson’s take on the Bay of Pigs/Cuban Missile Crisis and U.S. intervention in Latin America. But ultimately, it still is not quite a “good” comic. Too many typos, campy scenes of heroism, and poorly-scripted dialogue.

Star Rating: 2 1/2 stars – a nice try.

(Part 1/4)

Some people are entirely against everything that he embodied. Some defend everything he ever did, whole-sale. Some swear to his beliefs, and yet decry the methods by which he carried them out. And still there are others who, 40 years after his death, wear his face on a t-shirt but don’t know his name.

Che Guevera. The middle-class Argentinian med student who went on to help launch the Cuban Revolution. He re-defined the rules of modern warfare, modernized the practical application of socialism, fought battles on three continents, and died at the hands of the CIA and their Bolivian counterparts.

No matter where you stake your claim in the spectrum, there is no doubt that Che was the socialist Dos Equis “World’s Most Interesting Man” for his time. But he was no pop star… the polarization of opinions of Che Guevera and his lasting image remain a testament to how much impact his ideas and his actions really had.

As someone who has read Che’s speeches, writings, seen the movies, been to various forums and seminars about the man’s life (including several in Cuba), I say this: the offerings of a 100-pg comic book covering the epic that was his life stand to face a tall order. Fidel Castro could probably write 100 pages about Che’s fingernails. It’s a challenge, regardless of the quality of writers or the artists; a challenge that I took an interest in a few months ago when I began to notice the high number of Che comic book biographies out there.

Most of them (and all the ones I’m reviewing here) were released at the same time –2008 to 2009. It may have been in response to the popularity of Diarios de Motorcicleta (The Motorcycle Diaries) released to critical acclaim in 2004. Nonetheless, not all are equal. Of the four I’ve chosen to review (there are six in total that I have come across, but the other two are out of print / not available in Canada) they come from three different countries and use vastly different angles and resources by which to tell their story. This is part 1/4 of my findings.

“CHE: A Graphic Biography” written by Sid Jacobson with artwork by Ernie Colon, was published in 2009 by Hill & Wang (under a section called “Novel Graphics”).

What immediately strikes me about this book is its accessibility. This copy was actually a Christmas present from my parents—if they found it, they obviously didn’t need to look too hard. The cover points out that both Jacobson and Colon are New York Times best-selling authors. This is graphic novel marketing and packaging at its most efficient.

To me, the inside reminds me about that old saying of books and their covers. It’s page 6 and I’m already confused. Chronology of the events really jumps around, as the author tries to write about two different bike trips that Ernesto went on at different times in his life. Coincidentally, I quickly take note that the artwork seems a little confused as well, if only in regards to the time period: Latino motorcycle thugs from the 1930s probably didn’t sport skull decals, black leather jackets and, well, modern-looking chopper motorbikes.

A plus is that the book takes the time to illustrate the political climate, more or less, of the major Latin American states at the time of Che’s trip, which I find useful and original—yet even this unique portion of the book tends to lack in terms of overall vision and context. For example, if the recurring themes in Che’s life revolve around wealth disparity (poverty, employment, suffrage) and U.S. meddling in the continent, then why are the descriptions of countries so scattered beyond this? Who cares that in 1951, Brazil ‘s executive branch consisted of a 9-man council? Proper context would have illustrated, perhaps, that over the last hundred years of Latin America there have been a thousand men who have come to power, elected or otherwise, on promises that were always broken…a continental legacy of despotism that is of down-right mythological proportions.

A plus is that the book takes the time to illustrate the political climate, more or less, of the major Latin American states at the time of Che’s trip, which I find useful and original—yet even this unique portion of the book tends to lack in terms of overall vision and context. For example, if the recurring themes in Che’s life revolve around wealth disparity (poverty, employment, suffrage) and U.S. meddling in the continent, then why are the descriptions of countries so scattered beyond this? Who cares that in 1951, Brazil ‘s executive branch consisted of a 9-man council? Proper context would have illustrated, perhaps, that over the last hundred years of Latin America there have been a thousand men who have come to power, elected or otherwise, on promises that were always broken…a continental legacy of despotism that is of down-right mythological proportions.

I find myself riding the fence with this book, looking for merit but noting mostly detractions, until the depiction of the last major battle of the Cuban Revolution, in Santa Clara, where guerrillas attacked a train car full of Batista’s soldiers. It is misleading at best, entirely historically inaccurate at worst.

The train was not attempting to escape; it was full of hundreds of reinforcements along with a ton of ammunition. Think about it; an army doesn’t “escape” in the middle of a battle—especially when their numbers are higher. Most of the 400-odd soldiers and officers survived, and were taken prisoner after a truce.

This scene and other historical inaccuracies, combined with scattered story-telling, poor research, and some eye-sore colour and design choices make this my least favourite of the biographies, despite its flashy cover.

My Rating: 1 star, and a pitying head-shake.

A People’s History of American Empire: Zinn’s Graphic Adaptation

It was two years ago this month – on January 27, 2010, that Howard Zinn passed on. He was 87 years old. While he was arguably the most important American historian of the 20th Century and wrote a library of work–including his milestone, A People’s History of the United States–a fun fact is that the last publication he released during his lifetime… was actually a comic book.

It was two years ago this month – on January 27, 2010, that Howard Zinn passed on. He was 87 years old. While he was arguably the most important American historian of the 20th Century and wrote a library of work–including his milestone, A People’s History of the United States–a fun fact is that the last publication he released during his lifetime… was actually a comic book.

Title: A People’s History of American Empire (A Graphic Adaptation) Author: Howard Zinn Artwork: Mike Konopacki Editor: Paul Buhle Published: 2008 through Metropolitan Books

The gravity of Zinn’s legacy tends to make singular reviews of his work impossible. A review of one work necessitates a contextual understanding of his life as a radical historian who in turn, participated in making history during his own time. That being said, I will assume that readers will go elsewhere to get their crash course on Zinn, so my review stays under 10,000 words.

This book is beautifully presented. It is now available in soft- or hard-cover, and at about 12″ x 20″, is a little too big to comfortably sit in my lap as I’m reading it. My assumption is that the creators chose a larger format because the work is so text-heavy.

That text is important, because Zinn is arguing a still-contested notion, and needs as much evidence to back up his arguments as possible. It begins with the annexation of Indigenous lands across what is now North America in the later 1800’s, and takes us to the present post-9/11 era of relative global military hegemony. Zinn’s thesis is relatively clear: all of modern U.S. history is a history of empire; however, there is a parallel history of life and resistance by many. This includes poor and working people, who have played major rolls through unions, churches, and other community groups; women, students, and minorities of many stripes have all had interesting parts to play in a history that is largely told, in Zinn’s words, from the perspective of only “certain white men” (implying the rich and powerful).

Compared to A People’s History of the United States, which first appeared as a piece of academic achievement, American Empire reminds me more of a documentary film. Zinn is shown giving a lecture at an anti-war event, introducing and concluding the book’s chapters, which jump to varying times and places. Major historical figures like Black Elk, Mark Twain, and Eugene Debs are in these chapters, speaking as if to the reader, in scripts pulled largely from their real-life quotations and writings. The creators have chosen to accent this large-scale historical narrative with Zinn’s own personal history, as a young unionist, a WWII Air Force bombardier, and finally, as a young radical professor during the Civil Rights and Vietnam War eras.

What you get here is an interwoven account of his research and his own personal account of the 20th Century. It’s a moving way to look at a history that was told to most of us very differently in school.

Visually, it’s all a lot to take in, especially if you want to appreciate the illustrations as well as the text. I see this book being most appreciated when you can read it in segments. This makes it perfect for classrooms or study group. Each chapter is about 6 pages.

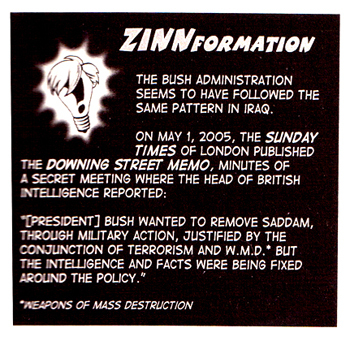

We are looking at a graphic adaptation of Zinn’s work. But we’re also looking at a graphic adaptation of the man as a modern-day intellectual icon. (Ex: These great little “Zinnformation” boxes pop up from time to time in the chapters, depicting a little light bulb with Howard’s tell-tale white hair-‘do.)

But just because I support the work in principle doesn’t mean the review is all roses, right? I have a few critiques of the book, rooted in my perspective as a comics lover + writer, and as a history enthusiast who cannot overestimate the impact Howard Zinn has had on my education.

I’ll get right to the point:

I’m not a fan of comic book adaptations–of books, movies: anything. My experience with them has been largely that they are a lose-lose product: the comic book becomes a simplified medium for what was in its first stage a more complete and highly-developed creative product. (Insert any comic book adaptation of anything here: Game of Thrones, The Last Unicorn, Ender’s Game, etc. etc. etc.) On the other hand, the comic medium is dis-serviced by simply being a highly-saleable vessel by which to re-release something that’s already out on the market. In short, if you’re doing a graphic adaptation, you’d better be bringing something incredibly special to the table.

In this regard, I think this graphic adaptation of Zinn’s past work has both some hits and misses.

First, let’s talk about the hits.

(+) Of course, a comic book makes available a lot of the information that Zinn has, largely, buried in pages upon pages of academic text, filled with all the usual footnotes and supplementary reading. So it’s accessible, and that’s especially important to young adults or classroom settings, as I mentioned before.

(+) The book does in fact compile some new information, largely the primary sources used to assemble its “interview”-styled segments with historical figures like that of Mark Twain shown above. That and the additions of Zinn’s personal experiences make it a more colourful work than any *one* of his texty-texts.

(+) Some of the graphics that have been added to this volume, including the contemporary photographs, political cartoons and other artwork of the time does much to enrich the narrative. It’s always illuminating to have this kind of media–text is, after all, highly prone to editorialization–but a photograph or political cartoon can reveal something of an un-altered reality for the time period. Now, some of the downers.

(-) Personally, I find the cartoon-ish fashioning of the illustrations to be a little out of the mood of the book. This is a serious, often grim, telling of American history–there are many chapters that would have rightly moved me to tears, if not for drawings that look like they came out of a storyboard for Quick-Draw McGraw. I would have gone with a different overall style. Still, even if the manner isn’t to my liking, at least it’s consistent, and professionally rendered.

(-) Many graphics are modified photographs–that’s fine–but what irks me is that whoever photo-shopped them didn’t clean them up. It’s like writing a milestone book and then not bothering to format it properly. I don’t know why political comic books continue to disappoint me in this arena. It’s as if they see the quality of form and content as mutually exclusive. Or they think that readers just won’t care.

Some won’t: that’s true.

But for comic book connoisseurs as well as artistically-minded comic readers, this is what ultimately determines the quality of the work… i.e. the amount of love that went into it.

In my opinion, we’re in the beginning stages of a second golden era for comic books–with political and historical comics, for the first time, being seriously included in the festivities. The last thing you want is to be invited to that party and then let people down. Think I’m making a mountain out of mole hill? Maybe. I’ll come back to this in a moment…

…first I gotta to drill into your heads, again, why Howard Zinn was (and IS) so important. Don’t worry, it won’t take 10,000 words.

As I touched on before, when A People’s History of the United States was published in 1980, the words “People’s History” were neither a mainstream term nor a methodology. Academically speaking, it was a new argument: History didn’t have to be that of kings and “great men”, or, as Henry Kissinger put it, “the memory of states”. It was revolutionary. He introduced the historical equivalent of ‘the 99%”–an overwhelming proportion of human history sits in the stories and memories of common folk–and it was right under everyone’s noses, being largely ignored.

By 2008 when this book came out, Zinn was already an icon. This book has led to countless additional volumes written or based on that first People’s History. Like supplementary reading satellites, they revolve around the foundation of that first work. Here are a few:

- Howard Zinn’s (A People’s History of) The Twentieth Century

- Voices of a People’s History of the United States

- A Young People’s History of the United States, adapted from the original text by Rebecca Stefoff;

- A People’s History of the United States: Teaching Edition

Audio renditions of his work are narrated by Matt Damon, Viggo Mortenson, and others moved by his work.

Here are a few books written by other historians, composing a “series” founded on Zinn’s original work:

- Chris Harman’s A People’s History of the World

- A People’s History of the Supreme Court by Peter Irons with Foreword by Zinn

- A People’s History of Sports in the United States by Dave Zirin with an introduction by Howard Zinn

- The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World by Vijay Prashad

- A People’s History of the American Revolution by Ray Raphael

- A People’s History of the Civil War by David Williams

- A People’s History of the Vietnam War by Jonathan Neale

- The Mexican Revolution: A People’s History by Adolfo Gilly

What we are reviewing here is one of those publications. There is no other historian, mainstream of no, who can claim such a franchise, nor such a significant intellectual imprint.

What I’m trying to say is this: when I see imperfections in comic books, I think of two things:

– Creators/editors who lack experience in comic books (lots of indie/underground comics, as well as quite a few political comics, whose creators are firstly activists or academics; not comic book-makers). This often points to a lack of necessary funds and time.

– A rushed attempt to make money (most often the case in the department of “Comic Book Adaptations’… yet another reason for my distaste of the category…)

With People’s History of American Empire, with all due respect, a little may be true of both.

But it kind of doesn’t matter what I think. At the end of the day, what’s important to me is figuring out what the end user (the reader) is thinking; and that’s what I’ve tried to do here.

Why does it concern me? Because I would never want someone to read this book and find out that their lasting impression of a work was “rushed attempt to make money”–when its origins are so profoundly the opposite in motivation.

Political comics will catch on. As the importance of non-fiction comics grows, more and more investment will be put into making a product with a cause that is indistinguishable from the mainstream players. But for now, the fact that this is one of the most well-circulated political comics of the past few years shows that we’ve got a little ways to go.

NMG

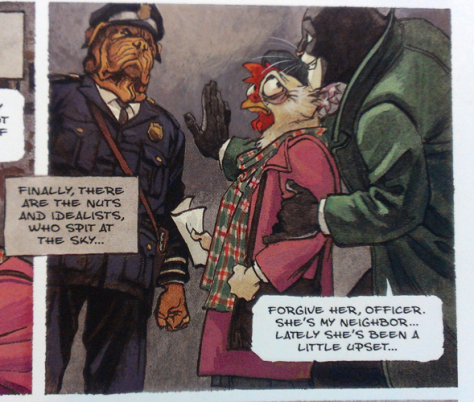

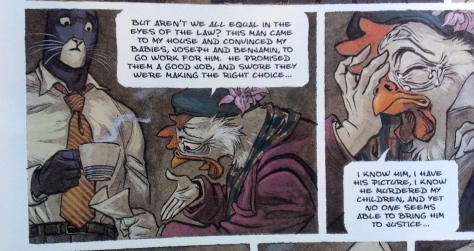

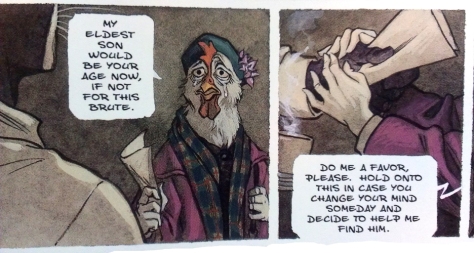

BLACKSAD clip – “Spit at the Sky”

Just came across this last night… it’s from one of my favorite–generally non-political–comic books, BlackSad, by Juan Dias Canales and Juanjo Guarnido from Spain. Amazing artwork, great film-noir style plots with all the twists and turns… and all with cats, dogs, foxes, toads, birds, and all other manner of anthropomorphic folk.

This one hit home, and given its angle, I thought I’d share with the folks who follow my Political Comics Review. All work (c) Canales and Guarnido. Enjoy, (and get a copy of the full book here).