In this installment from the “Anarchist Current,” the Afterword to Volume Three of my anthology of anarchist writings, Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas, I focus on Ivan Illich and his critique of modern institutions, “disabling” professions, and the commodification of everyday life, and his alternative vision of a convivial society. Illich was friends with Paul Goodman, who helped to inspire Illich to write one of his best known books, Deschooling Society. Like Goodman, Illich has unjustly faded from public view since his death (in 2002). By that time he had already become marginalized, as even “liberal” intellectual forums, like the New York Review of Books, had long since ceased to discuss his work, following a brief intellectual opening in the late 1960s and the 1970s (with Noam Chomsky suffering a similar fate). While Illich never described himself as an anarchist, some of his critics did. I included one of his essays in Volume Two of the Anarchism anthology. Anarchists can still benefit from his critique of modern industrialized society.

Toward a Convivial Society

In the 1970s, Ivan Illich, who was close to Paul Goodman, called for the “inversion of present institutional purposes,” seeking to create a “convivial society,” by which he meant “autonomous and creative intercourse among persons, and intercourse of persons with their environment.” For Illich, as with most anarchists, “individual freedom [is] realized in mutual personal interdependence,” the sort of interdependence which atrophies under the state and capitalism. The problem with present institutions is that they “provide clients with predetermined goods,” making “commodities out of health, education, housing, transportation, and welfare. We need arrangements which permit modern man to engage in the activities of healing and health maintenance, learning and teaching, moving and dwelling.” He argued that desirable institutions are therefore those which “enable people to meet their own needs.”

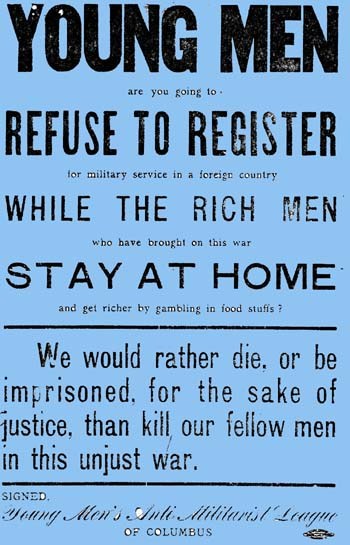

Where Illich parted company with anarchists was in his endorsement of legal coercion to establish limits to personal consumption. He proposed “to set a legal limit to the tooling of society in such a way that the toolkit necessary to conviviality will be accessible for the autonomous use of a maximum number of people” (Volume Two, Selection 73). For anarchists, one of the problems with coercive legal government is that, in the words of Allan Ritter, the “remoteness of its officials and the permanence and generality of its controls cause it to treat its subjects as abstract strangers. Such treatment is the very opposite of the personal friendly treatment” appropriate to the sort of convivial society that Illich sought to create (Volume Three, Selection 18).

Anarchists would agree with Illich that existing political systems “provide goods with clients rather than people with goods. Individuals are forced to pay for and use things they do not need; they are allowed no effective part in the process of choosing, let alone producing them.” Anarchists would also support “the individual’s right to use only what he [or she] needs, to play an increasing part as an individual in its production,” and the “guarantee” of “an environment so simple and transparent that all [people] most of the time have access to all the things which are useful to care for themselves and for others.” While Illich’s emphasis on “the need for limits of per capita consumption” may appear to run counter to the historic anarchist communist commitment to a society of abundance in which all are free to take what they need, anarchists would agree with Illich that people should be in “control of the means and the mode of production” so that they are “in the service of the people” rather than people being controlled by them “for the purpose of raising output at all cost and then worrying how to distribute it in a fair way” (Volume Two, Selection 73).

Illich proposed that “the first step in a more general program of institutional inversion” would be the “de-schooling of society.” By this he meant the abolition of schools which “enable a teacher to establish classes of subjects and to impute the need for them to classes of people called pupils. The inverse of schools would be opportunity networks which permit individuals to state their present interest and seek a match for it.” Illich therefore went one step beyond the traditional anarchist focus on creating libertarian schools that students are free to attend and in which they choose what to learn (Volume One, Selections 65 & 66), adopting a position similar to Paul Goodman, who argued that children should not be institutionalized within a school system at all (1964).

By replacing the commodity of “education” with “learning,” which is an activity, Illich hoped to move away from “our present world view, in which our needs can be satisfied only by tangible or intangible commodities which we consume” (Volume Two, Selection 73). The “commodification” of social life is a common theme in anarchist writings, from the time when Proudhon denounced capitalism for reducing the worker to “a chattel, a thing” (Volume One, Selection 9), to George Woodcock’s critique of the “tyranny of the clock,” which “turns time from a process of nature into a commodity that can be measured and bought and sold like soap or sultanas” (Volume Two, Selection 69).

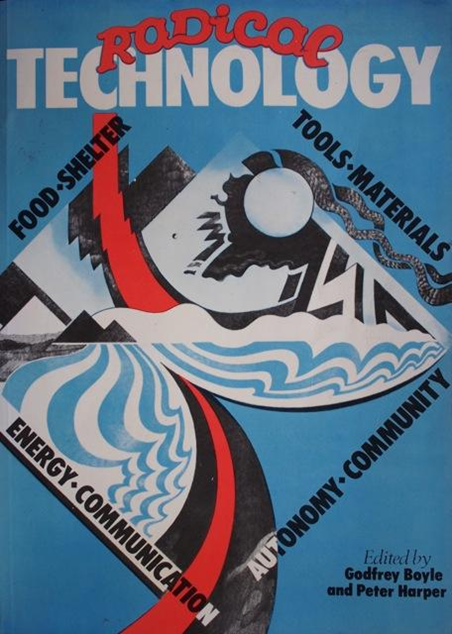

Illich criticized those anarchists who “would make their followers believe that the maximum technically possible is not simply the maximum desirable for a few, but that it can also provide everybody with maximum benefits at minimum cost,” describing them as “techno-anarchists” because they “have fallen victim to the illusion that it is possible to socialize the technocratic imperative” (Volume Two, Selection 73). It is not clear to whom Illich was directing these comments, but a few years earlier Richard Kostelanetz had written an article defending what he described as “technoanarchism,” in which he criticized the more common anarchist stance critical toward modern technology (Volume Two, selection 72).

Kostelanetz suggested that “by freeing more people from the necessity of productivity, automation increasingly permits everyone his artistic or craftsmanly pursuits,” a position similar to that of Oscar Wilde (Volume One, Selection 61). Instead of criticizing modern technology, anarchists should recognize that the “real dehumanizer” is “uncaring bureaucracy.” Air pollution can be more effectively dealt with through the development of “less deleterious technologies of energy production, or better technologies of pollutant-removal or the dispersion of urban industry.” Agreeing with Irving Horowitz’s claim that anarchists ignored “the problems of a vast technology,” by trying to find their way back “to a system of production that was satisfactory to the individual producer, rather than feasible for a growing mass society,” Kostelanetz argued that anarchists must now regard technology as “a kind of second nature… regarding it as similarly cordial if not ultimately harmonious, as initial nature” (Volume Two, Selection 72).

In response to Horowitz’s comments, David Watson later wrote that the argument “is posed backwards. Technology has certainly transformed the world, but the question is not whether the anarchist vision of freedom, autonomy, and mutual cooperation is any longer relevant to mass technological civilization. It is more pertinent to ask whether freedom, autonomy, or human cooperation themselves can be possible in such a civilization” (Watson: 165-166). For Murray Bookchin, “the issue of disbanding the factory—indeed, of restoring manufacture in its literal sense as a manual art rather than a muscular ‘megamachine’—has become a priority of enormous social importance,” because “we must arrest more than just the ravaging and simplification of nature. We must also arrest the ravaging and simplification of the human spirit, of human personality, of human community… and humanity’s own fecundity within the natural world” by creating decentralized ecocommunities “scaled to human dimensions” and “artistically tailored to their natural surroundings” (Volume Two, Selection 74).

Robert Graham