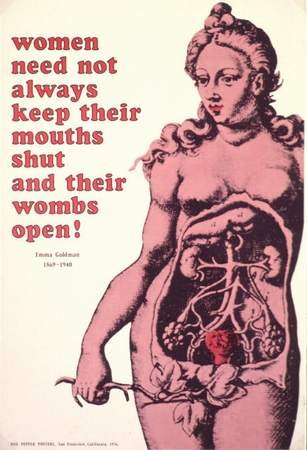

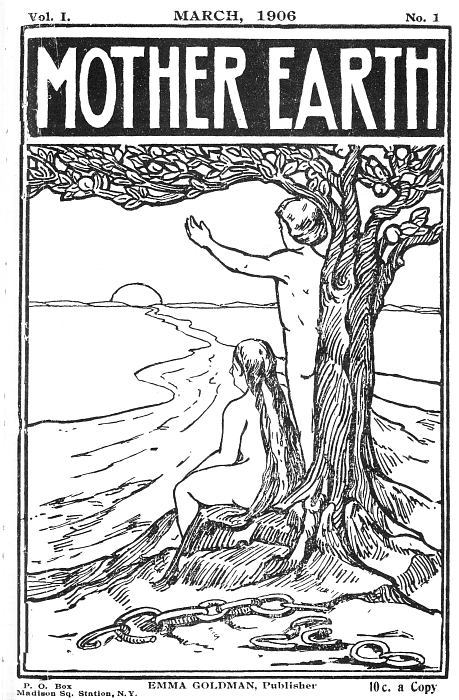

Emma Goldman wrote and lectured on a wide variety of topics, from anarchism and syndicalism to education, the modern drama, atheism, children, birth control, love, marriage, jealousy and prostitution. In this rarely republished essay, she discusses the pioneering feminist, Mary Wollstonecraft, author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, which Wollstonecraft wrote during the 1789 French Revolution in response to those male revolutionaries whose sole focus was on the “rights of men.” Goldman’s essay was recently reprinted in Black Flag, No. 227 (Black Flag is celebrating its 40th anniversary. Readers who would like to see Black Flag continue can make contributions here).

Emma Goldman wrote and lectured on a wide variety of topics, from anarchism and syndicalism to education, the modern drama, atheism, children, birth control, love, marriage, jealousy and prostitution. In this rarely republished essay, she discusses the pioneering feminist, Mary Wollstonecraft, author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, which Wollstonecraft wrote during the 1789 French Revolution in response to those male revolutionaries whose sole focus was on the “rights of men.” Goldman’s essay was recently reprinted in Black Flag, No. 227 (Black Flag is celebrating its 40th anniversary. Readers who would like to see Black Flag continue can make contributions here).

Emma Goldman: Mary Wollstonecraft, Her Tragic Life and Her Passionate Struggle for Freedom

The Pioneers of human progress are like the Seagulls, they behold new coasts, new spheres of daring thought, when their co-voyagers see only the endless stretch of water. They send joyous greetings to the distant lands. Intense, yearning, burning faith pierces the clouds of doubt, because the sharp ears of the harbingers of life discern from the maddening roar of the waves, the new message, the new symbol for humanity.

The latter does not grasp the new, dull, and inert, it meets the pioneer of truth with misgivings and resentment, as the disturber of its peace, as the annihilator of all stable habits and traditions.

Thus the pathfinders are heard only by the few, because they will not tread the beaten tracks, and the mass lacks the strength to follow into the unknown.

In conflict with every institution of their time since they will not compromise, it is inevitable that the advance guards should become aliens to the very one[s] they wish to serve; that they should be isolated, shunned, and repudiated by the nearest and dearest of kin. Yet the tragedy every pioneer must experience is not the lack of understanding – it arises from the fact that having seen new possibilities for human advancement, the pioneers can not take root in the old, and with the new still far off they become outcast roamers of the earth, restless seekers for the things they will never find.

They are consumed by the fires of compassion and sympathy for all suffering and with all their fellows, yet they are compelled to stand apart from their surroundings. Nor need they ever hope to receive the love their great souls crave, for such is the penalty of a great spirit, that what he receives is but nothing compared to what he gives.

Such was the fate and tragedy of Mary Wollstonecraft. What she gave the World, to those she loved, towered high above the average possibility to receive, nor could her burning, yearning soul content itself with the miserly crumbs that fall from the barren table of the average life.

Mary Wollstonecraft came into the World at a time when her sex was in chattel slavery: owned by the father while at home and passed on as a commodity to her husband when married. It was indeed a strange World that Mary entered into on the twenty-seventh of April 1759, yet not very much stranger than our own. For while the human race has no doubt progressed since that memorable moment, Mary Wollstonecraft is still very much the pioneer, far ahead of our own time.

She was one of many children of a middle-class family, the head of which lived up to his rights as master by tyrannizing his wife and children and squandering his capital in idle living and feasting. Who could stay him, the creator of the universe? As in many other things, so have his rights changed little, since Mary’s father’s time. The family soon found itself in dire want, but how were middle-class girls to earn their own living with every avenue closed to them? They had but one calling, that was marriage. Mary’s sister probably realized that. She married a man she did not love in order to escape the misery of the parents’ home. But Mary was made of different material, a material so finely woven it could not fit into coarse surroundings. Her intellect saw the degradation of her sex, and her soul – always at white heat against every wrong – rebelled against the slavery of half of the human race. She determined to stand on her own feet. In that determination she was strengthened by her friendship with Fannie Blood, who herself had made the first step towards emancipation by working for her own support. But even without Fannie Blood as a great spiritual force in Mary’s life, nor yet even without the economic factor, she was destined by her very nature to become the Iconoclast of the false Gods whose standards the World demanded her to obey. Mary was a born rebel, one who would have created rather than submit to any form set up for her.

It has been said that nature uses a vast amount of human material to create one genius. The same holds good of the true rebel, the true pioneer. Mary was born and not made through this or that individual incident in her surroundings. The treasure of her soul, the wisdom of her life’s philosophy, the depth of her World of thought, the intensity of her battle for human emancipation and especially her indomitable struggle for the liberation of her own sex, are even today so far ahead of the average grasp that we may indeed claim for her the rare exception which nature has created but once in a century. Like the Falcon who soared through space in order to behold the Sun and then paid for it with his life, Mary drained the cup of tragedy, for such is the price of wisdom.

Much has been written and said about this wonderful champion of the eighteenth century, but the subject is too vast and still very far from being exhausted. The woman’s movement of today and especially the suffrage movement will find in the life and struggle of Mary Wollstonecraft much that would show them the inadequacy of mere external gain as a means of freeing their sex. No doubt much has been accomplished since Mary thundered against women’s economic and political enslavement, but has that made her free? Has it added to the depth of her being? Has it brought joy and cheer in her life? Mary’s own tragic life proves that economic and social rights for women alone are not enough to fill her life, nor yet enough to fill any deep life, man or woman. It is not true that the deep and fine man – I do not mean the mere male – differs very largely from the deep and fine woman. He too seeks for beauty and love, for harmony and understanding. Mary realized that, because she did not limit herself to her own sex, she demanded freedom for the whole human race.

To make herself economically independent, Mary first taught school and then accepted a position as Governess to the pampered children of a pampered lady, but she soon realized that she was unfit to be a servant and that she must turn to something that would enable her to live, yet at the same time would not drag her down. She learned the bitterness and humiliation of the economic struggle. It was not so much the lack of external comforts, that galled Mary’s soul, but it was the lack of inner freedom which results from poverty and dependence which made her cry out, “How can anyone profess to be a friend to freedom yet not see that poverty is the greatest evil.”

Fortunately for Mary and posterity, there existed a rare specimen of humanity, which we of the twentieth century still lack, the daring and liberal Publisher Johnson. He was the first to publish the works of Blake, of Thomas Paine, of Godwin and of all the rebels of his time without any regard to material gain. He also saw Mary’s great possibilities and engaged her as proofreader, translator, and contributor to his paper, the Analytical Review. He did more. He became her most devoted friend and advisor. In fact, no other man in Mary’s life was so staunch and understood her difficult nature, as did that rare man. Nor did she ever open up her soul as unreservedly to any one as she did to him. Thus she writes in one of her analytical moments:

“Life is but a jest. I am a strange compound of weakness and resolution. There is certainly a great defect in my mind, my wayward heart creates its own misery. Why I have been made thus I do not know and until I can form some idea of the whole of my existence, I must be content to weep and dance like a child, long for a toy and be tired of it as soon as I get it. We must each of us wear a fool’s cap, but mine alas has lost its bells and is grown so heavy, I find it intolerably troublesome.”

That Mary should write thus of herself to Johnson shows that there must have been a beautiful comradeship between them. At any rate, thanks to her friend she found relief from the terrible struggle. She found also intellectual food. Johnson’s rooms were the rendezvous of the intellectual elite of London. Thomas Paine, Godwin, Dr. Fordyce, the Painter Fuseli, and many others gathered there to discuss all the great subjects of their time.

Mary came into their sphere and became the very center of that intellectual bustle. Godwin relates how he came to hear Tom Paine at an evening arranged for him, but instead he had to listen to Mary Wollstonecraft, her conversational powers like everything else about her inevitably stood in the center of the stage.

Thus Mary could soar through space, her spirit reaching out to great heights. The opportunity soon offered itself. The erstwhile champion of English liberalism, the great Edmund Burke, delivered himself of a sentimental sermon against the French Revolution. He had met the fair Marie Antoinette and bewailed her lot at the hands of the infuriated people of Paris. His middle-class sentimentality saw in the greatest of all uprisings only the surface and not the terrible wrongs the French people endured before they were driven to their acts. But Mary Wollstonecraft saw and her reply to the mighty Burke, The Vindication of the Rights of Man, is one of the most powerful pleas for the oppressed and disinherited ever made.

It was written at white heat, for Mary had followed the revolution intently. Her force, her enthusiasm, and, above all, her logic and clarity of vision proved this erstwhile schoolmistress to be possessed of a tremendous brain and of a deep and passionately throbbing heart. That such should emanate from a woman was like a bomb explosion, unheard of before. It shocked the World at large, but gained for Mary the respect and affection of her male contemporaries. They felt no doubt, that she was not only their equal, but in many respects, superior to most of them.

“When you call yourself a friend of liberty, ask your own heart whether it would not be more consistent to style yourself the champion of Property, the adorer of the golden image which power has set up?

Security of Property! behold in a few words the definition of English liberty. But softly, it is only the property of the rich that is secure, the man who lives by the sweat of his brow has no asylum from oppression.”

Think of the wonderful penetration in a woman more than one hundred years ago. Even today there are few among our so-called reformers, certainly very few among the women reformers, who see as clearly as this giant of the eighteenth Century. She understood only too well that mere political changes are not enough and do not strike deep into the evils of Society.

Mary Wollstonecraft on Passion:

“The regulating of passion is not always wise. On the contrary, it should seem that one reason why men have a superior judgment and more fortitude than women is undoubtedly this, that they give a freer scope to the grand passion and by more frequently going astray enlarge their minds.

Drunkenness is due to lack of better amusement rather than to innate viciousness, crime is often the outcome of a superabundant life.

The same energy which renders a man a daring villain would have rendered him useful to society had that society been well organized.”

Mary was not only an intellectual, she was, as she says herself, possessed of a wayward heart. That is she craved love and affection. It was therefore but natural for her to be carried away by the beauty and passion of the Painter Fuseli, but whether he did not reciprocate her love, or because he lacked courage at the critical moment, Mary was forced to go through her first experience of love and pain. She certainly was not the kind of a woman to throw herself on any man’s neck. Fuseli was an easy-go-lucky sort and easily carried away by Mary’s beauty. But he had a wife, and the pressure of public opinion was too much for him. Be it as it may, Mary suffered keenly and fled to France to escape the charms of the artist.

Biographers are the last to understand their subject or else they would not have made so much ado of the Fuseli episode, for it was nothing else. Had the loud-mouthed Fuseli been as free as Mary to gratify their sex attraction, Mary would probably have settled down to her normal life. But he lacked courage and Mary, having been sexually starved, could not easily quench the aroused senses.

However. it required but a strong intellectual interest to bring her back to herself. And that interest she found in the stirring events of the French Revolution.

However, it was before the Fuseli incident that Mary added to her Vindication of the Rights of Man the Vindication of the Rights of Woman, a plea for the emancipation of her sex. It is not that she held man responsible for the enslavement of woman. Mary was too big and too universal to place the blame on one sex. She emphasized the fact that woman herself is a hindrance to human progress because she persists in being a sex object rather than a personality, a creative force in life. Naturally, she maintained that man has been the tyrant so long that he resents any encroachment upon his domain, but she pleaded that it was as much for his as for woman’s sake that she demanded economic, political, and sexual freedom for women as the only solution to the problem of human emancipation. “The laws respecting women made an absurd unit of a man and his wife and then by the easy transition of only considering him as responsible, she is reduced to a mere cypher.”

Nature has certainly been very lavish when she fashioned Mary Wollstonecraft. Not only has she endowed her with a tremendous brain, but she gave her great beauty and charm. She also gave her a deep soul, deep both in joy and sorrow. Mary was therefore doomed to become the prey of more than one infatuation. Her love for Fuseli soon made way for a more terrible, more intense love, the greatest force in her life, one that tossed her about as a willess, helpless toy in the hands of fate.

Life without love for a character like Mary is inconceivable, and it was her search and yearning for love which hurled her against the rock of inconsistency and despair.

While in Paris, Mary met in the house of T[homasl Paine where she had been welcomed as a friend, the vivacious, handsome, and elemental American, [Gilbert] Imlay. If not for Mary’s love for him the World might never have known of this Gentleman. Not that he was ordinary, Mary could not have loved him with that mad passion which nearly wrecked her life. He had distinguished himself in the American War and had written a thing or two, but on the whole he would never have set the World on fire. But he set Mary on fire and held her in a trance for a considerable time.

The very force of her infatuation for him excluded harmony, but is it a matter of blame as far as Imlay is concerned? He her all he could, but her insatiable hunger for love could never be content with little, hence the tragedy. Then too, he was a roamer, an adventurer, an explorer into the territory of female hearts. He was possessed by the Wanderlust, could not rest at peace long anywhere. Mary needed peace, she also needed what she had never had in her family, the quiet and warmth of a home. But more than anything else she needed love, unreserved, passionate love. Imlay could give her nothing and the struggle began shortly after the mad dream had passed.

Imlay was much away from Mary at first under the pretext of business. He would not be an American to neglect his love for business. His travels brought him, as the Germans say, to other cities and other loves. As a man that was his right, equally so was it his right to deceive Mary. What she must have endured only those can appreciate who have themselves known the tempest.

All through her pregnancy with Imlay’s child, Mary pined for the man, begged and called, but he was busy. The poor chap did not know that all the wealth in the world could not make up for the wealth of Mary’s love. The only consolation she found was in her work. She wrote The French Revolution right under the very influence of that tremendous drama. Keen as she was in her observation, she saw deeper than Burke, beneath all the terrible loss of life, she saw the still more terrible contrast between poverty and riches and [that] all the bloodshed was in vain so long as that contrast continued. Thus she wrote: “If the aristocracy of birth is leveled with the ground only to make room for that of riches, I am afraid that the morale of the people will not be much improved by the change. Everything whispers to me that names not principles are changed.” She realized while in Paris what she had predicted in her attack on Burke, that the demon of property has ever been at hand to encroach on the sacred rights of man.

With all her work Mary could not forget her love. It was after a vain and bitter struggle to bring Imlay to her that she attempted suicide. She failed, and to get back her strength she went to Norway on a mission for Imlay. She recuperated physically, but her soul was bruised and scarred. Mary and Imlay came together several times, but it was only dragging out the inevitable. Then came the final blow. Mary learned that Imlay had other affairs and that he had been deceiving her, not so much out of mischief as out of cowardice.

She then took the most terrible and desperate step, she threw herself into the Thames after walking for hours to get her clothing wet [so] that she may surely drown. Oh, the inconsistencies, cry the superficial critics. But was it?

In the struggle between her intellect and her passion Mary had suffered a defeat. She was too proud and too strong to survive such a terrible blow. What else was there for her but to die?

Fate that had played so many pranks with Mary Wollstonecraft willed it otherwise. It brought her back to life and hope, only to kill her at their very doors.

She found in Godwin the first representative of Anarchist Communism, a sweet and tender camaraderie, not of the wild, primitive kind but the quiet, mature, warm sort, that soothes one like a cold hand upon a burning forehead. With him she lived consistently with her ideas in freedom, each apart from the other, sharing what they could of each other.

Again Mary was about to become a mother, not in stress and pain as the first time, but in peace and surrounded by kindness. Yet so strange is fate, that Mary had to pay with her life for the life of her little girl, Mary Godwin. She died on September tenth, 1797, barely thirty-eight years of age. Her confinement with the first child, though under the most trying of circumstances, was mere play, or as she wrote to her sister, “an excuse for staying in bed.” Yet that tragic time demanded its victim. Fannie Imlay died of the death her mother failed to find. She committed suicide by drowning, while Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin became the wife of the sweetest lark of liberty, Shelley.

Mary Wollstonecraft, the intellectual genius, the daring fighter of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth Centuries, Mary Wollstonecraft, the woman and lover, was doomed to pain because of the very wealth of her being. With all her affairs she yet was pretty much alone, as every great soul must be alone – no doubt, that is the penalty for greatness.

Her indomitable courage in behalf of the disinherited of the earth has alienated her from her own time and created the discord in her being which alone accounts for her terrible tragedy with Imlay. Mary Wollstonecraft aimed for the highest summit of human possibilities. She was too wise and too worldly not to see the discrepancy between her world of ideals and her world of love that caused the break of the string of her delicate, complicated soul.

Perhaps it was best for her to die at that particular moment. For he who has ever tasted the madness of life can never again adjust himself to an even tenor. But we have lost much and can only be reconciled by what she has left, and that is much. Had Mary Wollstonecraft not written a line, her life would have furnished food for thought. But she has given both, she therefore stands among the world’s greatest, a life so deep, so rich, so exquisitely beautiful in her complete humanity.

Emma Goldman

1911

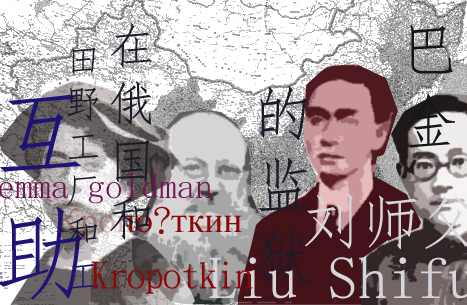

At the 1907 International Anarchist Congress in Amsterdam, Emma Goldman (1869-1940) and Max Baginski (1864-1943) spoke on the relationship between individualism, autonomy and organization, supporting a conception of anarchist organization which respects individual autonomy. Goldman and Baginski had traveled from the United States to attend the Congress. As Baginski makes clear, their argument that individuality and autonomy can and must be respected in anarchist organizations in no way signified opposition to such organizations, such as those favoured by the anarcho-syndicalists, whose views were represented by Amadée Dunois in his previously posted speech at the Congress. Emma Goldman’s positive assessment of anarcho-syndicalism, “Syndicalism: Its Theory and Practice,” is reproduced as Selection 59 in Volume One of Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas.

At the 1907 International Anarchist Congress in Amsterdam, Emma Goldman (1869-1940) and Max Baginski (1864-1943) spoke on the relationship between individualism, autonomy and organization, supporting a conception of anarchist organization which respects individual autonomy. Goldman and Baginski had traveled from the United States to attend the Congress. As Baginski makes clear, their argument that individuality and autonomy can and must be respected in anarchist organizations in no way signified opposition to such organizations, such as those favoured by the anarcho-syndicalists, whose views were represented by Amadée Dunois in his previously posted speech at the Congress. Emma Goldman’s positive assessment of anarcho-syndicalism, “Syndicalism: Its Theory and Practice,” is reproduced as Selection 59 in Volume One of Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas.