Top Eleven Dollars & Sense Charts and Graphs of 2018

This article is from Dollars & Sense: Real World Economics, available at http://www.dollarsandsense.org

This is a web-only article.

It’s the end of the year, and you know what that means. ’Tis the season for Top Ten lists! Here at Dollars & Sense, we try to tell the most important stories about economic life, in the United States and around the world, in a number of different ways. And one of those ways is charts and graphs.

Here we have compiled our favorite graphs from the past year of Dollars & Sense. They’re not in rank order, so it’s not a countdown to the #1 Greatest Graph of the Year. Rather, we think that, together, these charts and graphs present a compelling picture of current economic issues. And again, for the third year in a row, we invoke the spirit of Nigel Tufnel and cranked it up to eleven.

—Chris Sturr, co-editor(Note: Not all of the articles featuring these graphs are posted online. To order back issues, click here, or subscribe to see what you’ve been missing.)

Stock Market and Interest Rate

1 Asset bubbles erode the industrial base. Most heterodox economists argue that the Fed’s job is to keep interest rates low to promote investment in equipment that creates jobs. However, if rising asset markets pull money out of the production process, and if low interest rates promote rising asset markets, then this conclusion requires modification. Economist Thomas Palley suggested in 2005 that the Fed could require more collateral for the types of loans used to invest in certain assets—a second way the Fed could reduce asset bubbles that would not rely upon the “blunt instrument” of interest rates. There will be many who do not want to imagine that a stock market bubble can do harm to the real economy. However, the rate at which America’s social fabric is tearing is too rapid for putting our heads in the sand. At least that’s the view from Keene, New Hampshire.

(From: Marie Christine Duggan, feature, Rising Asset Bubbles Distort the Industrial Base: Lessons from MPB in Keene, N.H., 1987–2003, March/April 2018.)

Democratic Vote-Share by Region, 1976–2016

2 Regional economics affects politics. Through the 1980s, the Democratic Party represented poorer parts of the country and campaigned for broad-based economic growth with industrial policy, business regulations, and income redistribution. Since the economic turmoil of the 1970s, however, and with the Democrats’ embrace of the Civil Rights movement and the Republicans’ embrace of Nixon’s “Southern Strategy,” the two parties have shifted. The Democrats now represent the more prosperous and cosmopolitan regions while Republicans represent the regions left behind by economic growth. The new (and influential) affluent component of the Democrats’ base has pulled them away from policies to promote shared regional growth, such as support for managed trade or industrial policy, even while Republicans remain tied to neoliberal policies of fiscal austerity and industrial deregulation that hurt many of their own supporters. While the Democrats continue to support elements of the social safety net, such as Social Security, their support for income redistribution has been softened, as when Democrat Bill Clinton supported repeal of the Aid to Families with Dependent Children.

(From: Gerald Friedman, Economy in Numbers, Growing Together, Flying Apart: Regional Disparities in American Politics and Economics, March/April 2018.)

Share of Public- and Private-Sector Workers in Unions, 1968–2000, 1973–2007

3 After rising sharply in the 1960s and early 1970s, the public-sector unionization rate has remained steady even as the private-sector rate has declined. In the early 1970s, the share of workers belonging to unions was higher in the private than in the public sector, and less than 20% of all union members were in the public sector. Public-sector unionization rates continued to rise through the 1970s, however, and passed the declining unionization rate in the private sector in 1974. The public sector advantage has only grown since then. Today, half of all union members are in the public sector, and the unionization rate there, 34%, is over five times that of private sector workers, at 6%.

(From: Gerald Friedman, Economy in Numbers, Why Janus Matters, May/June 2018.)

Share of Non-Security Public-Sector Jobs by Race and Gender

4 Women, African Americans, and Latinos are much more likely to work in the public sector (apart from the police and corrections) than are white men, and are therefore much more likely to belong to public-sector unions. This is largely due to the large share of caring, teaching, and clerical jobs in the public sector—all jobs disproportionately held by women and by racial and ethnic minorities. Nearly 16% of all women are employed in the public sector, as are almost 12% of African-American workers and 8% of Hispanics, compared with barely 7% of white men. This concentration of women and minority workers means that the Janus case is particularly important to these workers.

Source: Spreadsheet “Public-Sector Workers Unions” tab “Emp by Race and Gender” from BLS household data survey (bls.gov).

(From: Gerald Friedman, Economy in Numbers, Why Janus Matters, May/June 2018.)

Growth Rate of Real GDP, 1995 to 2018: Percent Change from Previous Year

Note: (The 2018 figure is the Fed's estimate.)

5 Is the U.S. economy really in “great shape”? Advocates of the “great shape” appraisal cite what they claim is a strong rate of economic growth and a very low unemployment rate as prime evidence that the economy is doing well. As to the rate of economic growth, it is only rapid in relation to the years since the Great Recession. Even by that standard, GDP is not doing especially well. The Fed’s growth forecast for 2018 is only 2.8%. While higher than the rate for 2016 and 2017, this is below the 2.9% growth of 2015.

(From: Arthur MacEwan, Ask Dr. Dollar, “Why Is the Fed Raising Interest Rates?,” July/August 2018.)

Federal Government Debt Held by the Public as a Share of GDP, United States, 1960–2016

6 The debt burden has gone up. The debt burden of the federal government has been steadily increasing since the mid-1970s, except for a short period in the late 1990s when relatively rapid economic growth and Clinton tax increases briefly drove down the deficit. Because of rising deficits, especially since 2002, the federal government now owes American and foreign debt-holders nearly 80% of GDP. The Congressional Budget Office has projected that in the next decade, federal debt will rise to nearly 100% of the GDP.

(From: Gerald Friedman, Economy in Numbers, “The Fiscal Crisis of the State: Rich capitalist countries rely on deficits to maintain growth and employment,” July/August 2018.)

Deficit Share of Exogenous Spending

7 Deficits have been key to maintaining growth. Instead of private investment and exports, since the 1970s, rising government deficits have been increasingly important in maintaining economic growth in the United States. While deficits were relatively small and had relatively little economic effect outside of periods of war or recession before 1980, since then they have been used regularly to maintain economic growth. Government deficits have substituted for falling private investment demand. In short, we need government to maintain economic growth and employment because private capitalists are no longer interested in investing in the United States.

(From: Gerald Friedman, Economy in Numbers, “The Fiscal Crisis of the State: Rich capitalist countries rely on deficits to maintain growth and employment,” July/August 2018.)

Protective Services Employees per 10,000 Workers, Early 2000s, U.S. vs. Europe

8 The share of the work force engaged in social control is larger in the United States than other countries, based on comparable data for 2000. That year the U.S. figure for supervisory labor, the largest component of the total, was 14.7%. For Sweden, the figure was 4.2%; for Spain, 6.7%; for Canada, 8.5%; and for the United Kingdom, a close second at 13.4%. hy the differences? It’s hard to be sure. But there is a suggestive correlation across countries between the share of “protective services” in the labor force and the degree of inequality. (“Protective services” is a Bureau of Labor Statistics category, including police and private guards, but also including other groups such as fire fighters that are not involved in social control; those other groups are excluded in this chart.) Right at the top in both the share of labor in protective services and inequality is the United States. But the relation is clear among the whole group of countries included in the diagram.

(From: Arthur MacEwan, Ask Dr. Dollar, “How Much of the U.S. Economy Is Devoted to Social Control?,” September/October 2018.)

Unemployment by Education Level

9 Even in the depths of the Great Recession, unemployment was mostly a problem for non-college graduates. Unemployment for college graduates hit 5.0% at its peak, less than a third of the peak rate for those without a high school diploma (15.8%). The recovery has disproportionately benefited those with less education, with unemployment rates for college graduates falling by nearly 11% while those for college graduates have fallen by less than 3%.

(From: Gerald Friedman, Economy in Numbers, “What Is Happening With Unemployment?,” September/October 2018.)

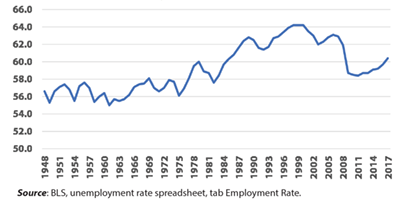

Emplyment-to-Population Ratio

10 While the rate of unemployment has fallen sharply, millions of Americans are still without work. Many people who are out of work are not included even in the U-6 measure because they have lately given up looking for paid work. From the 1970s to the late 1990s, the share of Americans with jobs rose steadily from around 55% to over 64% with the entry of millions of women into the paid labor force. Since 2000, this movement of women into the paid labor force has largely stopped, while growing numbers of men have left the labor force, abandoning the search for paid work. Because these people are not counted in our official measures of unemployment or labor underutilization, this loss of productive labor, and the sense of self-worth that comes with productive work, are not considered when policymakers say we have a “full-employment economy.”

(From: Gerald Friedman, Economy in Numbers, “What Is Happening With Unemployment?,” September/October 2018.)

GDP Compared to 2007 Projections: Japan, U.S., the EU, and the U.K.

11 Growth rates in the United States and elsewhere have been slow, and each year those slower growth rates have left GDP further and further behind the projected levels of GDP. In Japan, the eurozone, and the UK, as in the United States, recovery has failed to return the economies to what was seen as that potential, and the gap has continued to widen between actual GDP and potential. Growth rates, in other words, have remained below what was seen as normal before the crisis.

(From: Gerald Friedman, Economy in Numbers, “The Global Recovery from the Financial Crisis: Stagnation continues ten years after the fall of Lehman Brothers.,” November/December 2018.)

Did you find this article useful? Please consider supporting our work by donating or subscribing.