Number 45

In this issue:

- Rebelling against the industrial capitalist system

- “At the heart of this problem lies our sense of separation from nature”

- Abolishing dissent

- Does work set us free?

- Save Whitehawk Hill!

- Acorninfo

1. Rebelling against the industrial capitalist system

Is the human species finally waking up to the fact that industrial capitalism is murdering the planet and realising that we all have to take action to stop it?

The signs are currently looking good in England, where the Extinction Rebellion (XR) movement has appeared out of nowhere and mobilised thousands of people to block streets and engage in civil disobedience.

The first big day of action was on Saturday November 17, when some 6,000 people took to the streets of London.

They blocked five London bridges and planted trees on Parliament Square. More than 80 people were arrested.

Said Gail Bradbrook of XR: “This is an act of mass civil disobedience. This is the start of an international rebellion protesting the lack of action on the ecological crisis”.

There were swarming road blocks across London in the run-up to Rebellion Day 2, announced for Saturday November 24, 10am to 5pm at Parliament Square.

The Rebellion has also started to take off elsewhere, such as Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and Ireland.

Some question marks have been raised in anti-capitalist circles about the XR approach. For a start, the enthusiastic participation of pseudo-radical Guardian columnist George Monbiot, who too often mirrors his employers’ anti-left neoliberalism (see the Media Lens archives), has set alarm bells ringing.

A strangely deferential attitude to the police has also worried many. In an article in The Canary, Emily Apple highlighted a failure in XR circles to critique the fundamental relationship between the police, the state and corporations, pointing out: “Ultimately, the police are there to protect the interests of the state”.

She added: “It is our duty to rebel. But effective rebellion will mean facing the full force and the full power of the state, and being prepared for the consequences.

“No amount of statements of non-violence will stop the police going in with full force if what you’re doing is a threat to the state or corporate profit. It won’t stop fundamental police tactics of harassment and disruption; tactics designed to deliberately deter people from protesting”.

However, most would applaud the way XR has achieved what seemed impossible and ignited a whole new wave of public protest against industrial capitalism.

If you believe in a full diversity of tactics, then you have to wish them well and hope that their misguided faith in the intentions of the UK’s police does not end with too many baton-bludgeoned limbs and skulls, when the corporate-owned state decides that XR’s disruptive tactics have gone far enough.

Another encouraging sign of a change in consciousness is the publication by the UK’s Anarchist Federation of a booklet (available online) called Capitalism Is Killing the Earth: An Anarchist Guide to Ecology.

The booklet rightly notes: “There has been wider understanding of environmental issues since mainstream publications such as Silent Spring, Gaia and An Inconvenient Truth; however, an anti-capitalist critique has been lacking”.

The aim of anarchists should therefore be to “make the link between capitalism and environmental degradation explicit in our politics and critique the role of the state in facilitating this”.

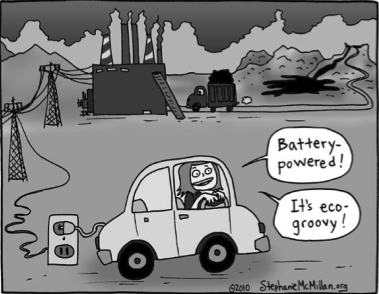

It tackles the issue of false solutions to the environmental meltdown, observing that most proposals for change do not question the overarching system of capitalism and the market economy: “The existence of private property, the appropriation of nature as a source of growth and production for profit instead of need are at the root of the problem, so they cannot be part of the solution”.

It was not clear to us, though, what is intended by the reference to a “primitivist” alternative society preventing people from “maintaining or increasing their standard of living”.

For the industrial capitalist mindset, “standard of living” is all about having a car and a dishwasher, flying abroad on holiday and fully participating in the capitalist economy. It is about buying and consuming.

Presumably the authors agree that a genuinely high “standard of living” would involve living freely in a community of equals, sharing the produce of the earth, breathing fresh air, eating uncontaminated food, waking each morning to the sound of birdsong or children’s laughter rather than of low-flying aircraft or the motorway at the end of the street.

The booklet says anarchists should “work more closely with groups such as Earth First!, Reclaim the Power and Rising Tide to further develop an activism which is both confrontational towards capitalism and is inclusive of local and global perspectives”.

We agree. A full convergence of anti-capitalism and anti-industrialism is long overdue. Industrialism and capitalism are not two separate phenomena but two aspects of the same thing.

Whether you first notice its existence from an environmental perspective or from a social one, industrial capitalism is readily identifiable as the enemy.

It is the enslaver of humanity, the stealer of land, the destroyer of community and, unless we can quickly drive a stake through its malignant heart, the murderer of our planet.

See also:

Fighting the cancer of economic growth

Degrowth and the death of capitalism

Envisioning a Post-Western World

End industrialism or humankind dies

Fleeing the black volcano of industrialism

2. “At the heart of this problem lies our sense of separation from nature”

In-depth interview with campaigner Geraldine of frackfree_eu

Thanks for agreeing to this interview. Could you tell us a little bit about who you are and what sort of campaigning you are involved in?

I grew up in a rural area. In some respects, I guess I kind of grew up in a bubble, not necessarily privileged, far from it in financial terms, but certainly sheltered from any social or environmental problems.

From a young age, I cared deeply about the environment, but I’d never engaged in any activism as such. I used to receive newsletters from the World Wildlife Fund, and feel concerned about all the animals whose habitats were endangered by deforestation, orangutans and koalas especially.

I was so concerned about deforestation, in fact, that I once replied to exam questions in tiny writing in order to save paper, drawing attention to the fact that trees are chopped down to make the paper. The teacher was outraged by my act, insisted I apologise, but I refused, so she put me on detention.

I wasn’t too bothered. Standing up for what’s right is something to be proud of and I wasn’t going to obey authority whose demands conflicted with my values. I always had a bit of a rebellious streak.

How I got into campaigning… My academic background is in languages. Throughout my studies, I’d never been involved in anything remotely political. It was only when doing a Masters in European Studies that I had my eyes opened to injustices I’d previously been unaware of – such as racism, the Israel / Palestine conflict, austerity. None of these issues made me angry enough to drop everything, though.

Then, in early 2011, I first became aware of fracking while in France with my boyfriend on a business trip, watching politicians on French TV engaged in a fiery debate about how it could contaminate the water.

The French term ‘gaz de schiste’ sounded less scary than the English equivalent ‘fracking’, so after a cursory look in the dictionary which translated ‘gaz de schiste’ as ‘shale gas’ I thought no more of it and just carried on focusing on my studies.

Little did I know at the time that the same technique was being proposed all across Europe and that France was to become the first country to ban it. It actually took me about six months to revisit the issue, after hearing news of earthquakes in Blackpool and seeing a documentary with French MEP José Bové at a fracking site somewhere in Poland.

Once I began ‘googling’ the term ‘fracking’, I was horrified. Then I learned that parts of Ireland were under threat too. Never in my life have I felt so incensed.

My first thought was: How could our government even consider giving permission to an industry that industrialises vast swathes of countryside and that has left a toll of death and destruction in every community where it has gained a foothold?

I’d never held politicians in much esteem anyway, feeling the system was designed to serve the better-off and those of us at the bottom rungs of the social ladder just have to work hard for everything and not rely on the state for help. As for voting, I’d only voted at one election as I felt elections were a farce.

Despite all this, it still took me aback at how Government can allow policies to be dictated by the interests of big business. What stunned me in particular is how these corporations fabricate lies in order to get what they want, repeating this mantra of jobs and growth as if nothing else mattered.

That the truth, the facts, the science, could be obscured for the sake of profit and self-interest ignited a fire in me like never before.

It was time for me to move beyond my comfort zone, beyond my material world and devote myself wholeheartedly to the cause by attending events and speaking out at them, working with people I’d never have imagined working with before, mobilising others to take action, organising events, travelling to places I’d never been – but ultimately sharing the truth about what fracking involves and how much suffering and harm it causes to every living being. Nowhere deserves to become a sacrifice zone, least of all the country where I grew up and love.

Just focusing on fracking for the moment, what do you think there is about it in particular – compared to mining, for instance, or other forms of industrialisation – that has triggered such a strong response in you, and in so many others who were not previously engaged in this kind of struggle?

Excellent and thought-provoking question! I’d be equally outraged about mining, though it is nowhere near as dangerous as fracking, to be honest, and have replied to consultations objecting to mining projects proposed in my country.

At the moment, communities in Northern Ireland, some of whom were previously licensed for fracking, are having to fight several mining projects. And at the height of the Romanian anti-fracking campaign, I remember meeting Romanians who were also involved in the campaign to save Rosia Montana from gold mining.

Anyone who opposes the raping and plundering of the land through fracking should also oppose mining or any industrial practice. Not to do so would be inconsistent, as all these practices pollute the air and water we all need to survive.

To answer your question properly, firstly, I think the term ‘fracking’ itself makes you sit up, encouraging you to delve deeper into the issue.

‘Shale gas’ on the other hand – as I experienced myself when I looked it up in the dictionary – tends to sound harmless, leaving you thinking, “Well, we need gas to heat our homes, don’t we?!” This is why the term ‘shale gas’ is preferred by the fracking industry, I believe.

And although ‘fracking’ may not have the same resonance in other languages, the documentary ‘Gasland’ by US filmmaker Josh Fox did much to popularise the term in non-English speaking countries, with translations into French, Romanian and Polish, and other languages too perhaps.

Secondly, I think the scale of what was being proposed across vast swathes of land, merely because of the geology, impacts thousands of communities. No other industry, in recent history at least, has impacted this many rural communities and no other industry has prompted so many places to enact bans and moratoria as a result of fierce grassroots opposition either.

Biologist Dr Sandra Steingraber and report co-author of the Compendium of Scientific, Medical, and Media Findings Demonstrating Risks and Harms of Fracking (Unconventional Gas and Oil Extraction) has called fracking “the worst thing I’ve ever seen.”

Having spent countless hours exploring fracking, I also believe that the impacts are far more severe than those associated with any other industrial process.

We have been fortunate to have had many experts – including Dr Steingraber, toxins expert Dr Marianne Lloyd-Smith, lawyer Helen Slottje, former oil and gas employee Jessica Ernst, as well as others who have seen fracking up close – come to Europe, warning us to fight with all our might.

And for good reason, because this industry has killed and harmed so many, from workers who have lost their lives in well blowouts or contracted cancers because of exposure to the toxic chemicals fracking uses and the NORM radiation the fracking process brings up – so well detailed by the late Dr Theo Colborn – to residents, children included, living in the gasfields suffering from severe neurological diseases caused by the toxic air pollution.

You also have suicides. The late George Bender, an Australian farmer, who was bullied for years by the fracking industry, ended up taking his own life a couple of years ago.

Then you have all the fish that have died because of fracking waste dumped in waterways and livestock that have suffered stillbirths. As Queensland gasfield refugee Brian Monk says, “You don’t live in gasfield. You die in one.”

Thirdly, I think fracking has raised the ire of so many because there is absolutely no need for it. The industry loves to tout energy security as an argument, but this is a complete red herring.

The reality is that fracking requires more energy than it creates – about five times more – and removes enormous quantities of our most precious resource, water, from the hydrological cycle forever.

There is also a global glut of gas, and gas demand across the EU has been falling steadily in recent years. So there can be no justification whatsoever for fracking.

Mining for raw materials, on the other hand, may be seen as justified by some. I mean, how many of us are willing to radically change our lifestyles so all the stuff relying on mining doesn’t need to be produced in the first place?

Try suggesting to people that they can and should live without a mobile phone (those of us who grew up without one survived perfectly well!) and it tends to provoke angry reactions.

Fourthly, the anti-fracking movement – largely grassroots and volunteer-based in nature – has done quite a good job of communicating the issue. Communication is crucial in mobilising people to take action. So often I see other struggles, equally worthy, being poorly communicated.

I think what’s important is that the communication is driven by local communities as much as possible. The corporate media loves to marginalise anti-fracking campaigners, portraying us as ‘environmentalists’, ‘green campaigners’, or worse, as ‘hippies’ and ‘treehuggers’.

In doing so, they give the impression that fracking is a fringe issue not worthy of everyone’s concern, when the complete opposite is true. In reality, the movement is made up of people from every background imaginable, from farmers and small business people to doctors and engineers.

Having communications driven by locals means you are able to capture all the cultural sensitivities too.

Framing our campaign as a struggle against corporate power and corporate-captured governments with ordinary people rising up against the odds also gets more people on board, in my experience. Again, unsurprisingly, the corporate media rarely frames our story this way.

Lastly, you definitely have a wider movement which vilifies the fossil fuel industry, and rightly so, because it exerts so much power over our governments. Other extractivist struggles, on the other hand, tend not to spark as much outrage, I feel.

Perhaps this is because any questioning of the capitalist system, and industrial civilisation as a whole, threatens so many depending on the system, especially NGOs who have far greater resources than grassroots groups to communicate environmental issues.

Shortly after I began researching fracking, I came across a book called ‘The Moneyless Man’ by Mark Boyle. Reading it led me to question industrial civilisation as a whole so, for me, fracking has always been just one part of a systemic problem.

At the heart of this problem lies our sense of separation from nature, a sense that we humans are in control of the earth’s resources and that we have the right to exploit them how we wish, oblivious to the fact that in doing so we are also destroying our only life-support system.

Living with less and challenging the system fuelling this greed and separation from nature has now become the focus of my efforts as a result of learning about fracking and wider environmental struggles.

What do you see as the main obstacles between the human species and a healthier, nature-connected future?

So much to say, but for me three obstacles in particular stand out: materialism, trust in authority and hope. Apologies in advance for what is going to be a lengthy reply.

– Materialism vs spirituality

First and foremost, I believe we need to abandon our material selves. For too long, we have seen ourselves as separate from nature, rather than a part of it. How can we forge a deep connection with nature, realising that all life is sacred, unless we are willing to strip ourselves of material belongings?

In becoming less materially-focused and more spiritual beings, we become less willing to destroy our life-support system, in my experience, as we feel a deeper attachment to nature.

How much do we really need to survive anyway? When you think about it carefully, very little. The only things I need to survive are a roof over my head and enough food.

Since discovering how earth’s precious resources are being raped and plundered and reading Mark Boyle’s book, a must-read for anyone who cares about the environment, I rarely buy anything I don’t need.

Each time I look at things now, I feel a sense of disgust even, wondering where the resources came from to make an item, what environments were polluted, if any slave labour or oppression was involved in its production, and so on.

I’ve also developed a repulsion towards money, choosing to work just enough to ensure my survival. What I’ve learned now is what you need more than anything in life are strong relationships.

Too often I see those involved in environmental struggles – especially in anglophone countries – advocating renewable forms of energy which also involve destroying nature. I find this strange.

Perhaps it is this focus on reducing carbon emissions, rather than a focus on protecting the sacred, protecting all life? Perhaps many are still trapped in the materialist mindset?

The cosmovision shared by Indigenous communities tells us that we are interdependent with one another, that harming any natural resource is harming ourselves. This is the vision I share too, because on a planet of finite resources only a radical shift in our way of thinking, away from the disconnected view of humans as separate from (and often as dominant over) nature, can lead to the profound changes we need to see.

As Babe actor and anti-fracking activist James Cromwell put it succinctly in an interview : “It is time to name the disease. Capitalism is a cancer. And the only way to defeat this cancer is to completely transform our way of living and our way of thinking about ourselves.”

– Trust in authority vs trust in one another

Years of intense campaigning against fracking and free trade agreements has taught me how corrupted by corporate power the entire system has become.

I’ve learned now that genuine solutions to our problems can only ever come from below, not from any authority, and certainly not from any form of government, be it local, regional or national, nor from any multilateral institution, no matter how well-meaning and benevolent that institution may appear on the surface.

The system can also embody the NGO and non-profit sector who, I’ve experienced, will tell you what the problems are but seldom bother to call into question the very structures that create these problems in the first place.

And because the root cause of these problems is never properly addressed, the same problems of exploitation surface time and time again.

To learn just how corrupted our authorities have become by corporate power, I’d advise everyone to invest themselves wholeheartedly in an issue like fracking where the links between a corporate-controlled government, a corporate-controlled media and a corporate-controlled police force fast become apparent.

On learning how corrupt the system is, you should come to the inescapable conclusion that it deserves to be dismantled.

Unfortunately, not everyone does realise this, perhaps because they rely on the system in some way – I don’t know.

For example, I remember being at a conference on free trade in the EU Parliament nearly two years ago listening to an NGO campaigner making a case for reforming the World Trade Organisation. Why would you want to reform an institution that was set up to facilitate corporate power, power which destroys nature?

Calling for institutions to reform is akin to justifying their existence in the first place. Instead, we need to be challenging their very existence and calling for them to be dismantled altogether.

A bit utopian, I know. But as corporate power dictates political policy more and more as corporations pursue ‘the race for what’s left, the global scramble for the world’s last resources’ – to borrow Michael Klare’s book title – it would be illogical to envision a nature-connected future within the confines of the current system.

We have a responsibility right now to challenge the system itself, the structures of authority which hold themselves up as legitimate, which declare themselves as bastions of freedom, democracy and the rule of law, structures which are desperately seeking legitimacy at a time of crumbling empires and dwindling resources.

This obviously includes all multilateral institutions, but also the state. From my involvement in the campaign against EU free trade agreements, or corporate power grabs as I prefer to call them, I’ve seen how the state facilitates corporate power, while dismissing scientific evidence, expert advice and public opinion.

How can we possibly hope to protect nature under such an oppressive, undemocratic system whose servants bow so readily to the will of corporations?

As empires crumble and we veer towards what can only be described as a corporate dystopia, we simultaneously witness authority figures struggling to convince us of their narratives.

Hence the crackdown on alternative media and this ‘fake news’ phenomenon, a phenomenon used by those in power to control what information the awakening masses have the right to access.

As you’ve put it succinctly, all across the world the “’democratic’ gloves are coming off, the ‘news’ is revealing itself to be nothing but desperate propaganda, the ‘freedom’ capitalism claims to deliver is being exposed to one and all as a hollow lie.”

It is more urgent than ever that we stop looking to the system for solutions, stop legitimising all structures of authority and any ‘agreements’ concluded by their ‘leaders’ and, most importantly of all, stop falling for any propaganda trying to convince us that this system in its many guises – capitalism, multilateralism, liberalism, etc. – needs rescuing.

Instead, we need to trust each other and cooperate with each other, rather than compete as this capitalist system conditions us to do. I would recommend everyone read CrimetheInc’s ‘To Change Everything‘ for further inspiration.

– Hope vs the responsibility of action

Lastly, we need to abandon the idea of hope, at least the sort of hope that fails to result in any tangible action. The hope that a small band of self-sacrificing activists will sort out the problems we face, the hope that political representatives will implement, of their own accord, policies that serve our interests rather than those of the 1%, the hope that a change in government will bring about the radical changes we need to see. Nature isn’t relying on us to hope for it, it is relying on us to do something to save it.

In one of your pieces, you share a remark by John Zerzan which resonates strongly with me: “There is an understandable, if misplaced, desire that civilization will cooperate with us and deconstruct itself. This mindset seems especially prevalent among those who shy away from resistance, from doing the work of opposing civilization”.

Sometimes I get the impression that people hope too much, but do too little.

In my experience of being involved in the Irish anti-fracking campaign – which lasted six years – many of us never hoped, never trusted our corporate-captured government, but many of us did work tirelessly to expose the political corruption and to ensure decision makers were held to account, listened to us and eventually did the right thing.

Anyone relying on hope without spending every breathing moment working on something to make things better is part of the problem, in my view. All campaigns need to start from the premise that you have a duty to act once you know the facts.

And once you learn about an issue as dangerous as fracking, of course, you feel a clear responsibility to take action, not out of fear – because fear kills the soul – but out of love, because you cherish the places and the lives that are under threat and don’t want to see them destroyed by greedy corporations.

As you put it so well: “Some human beings and their activities are acting as antigens, threatening the health of our species and our planetary superorganism. Other humans must therefore take on the role of antibodies”.

The last lines of Derrick Jensen’s essay ‘Beyond Hope‘ sum up the problem with hope perfectly: “When you give up on hope, you turn away from fear. And when you quit relying on hope, and instead begin to protect the people, things, and places you love, you become very dangerous indeed to those in power. In case you’re wondering, that’s a very good thing.”

For as long as anyone can remember, Western capitalism has claimed to be one and the same thing as “democracy”.

But as its global empire teeters on the point of collapse, its desperate attempts to cling to power have exposed this claim for the lie that it always was.

Much of the current wave of censorship and oppression is taking place on the internet – which has thus so far remained out of the direct control of the neoliberal system.

This October, Facebook and Twitter deleted the accounts of hundreds of users, including many alternative media outlets.

And credit for this seems to have been claimed by the German Marshall Fund of the United States, a very dodgy NATO-linked organisation (previously exposed by The Acorn here and here) which aims to maintain full-spectrum US neoliberal global control.

The grayzone project reported that the GMF’s Jamie Fly said the USA was “just starting to push back” against its enemies’ use of the internet, adding: “Just this last week Facebook began starting to take down sites. So this is just the beginning”.

The USA’s ongoing persecution, and planned prosecution, of WikiLeaks’ Julian Assange could likewise be regarded as part of the same “beginning” of neoliberalism’s overtly fascistic desire to crush any voices that dare to speak out against its imperial privilege.

Soo too could the coming to power in Brazil of the totalitarian neoliberal (or “plutofascist“) Jair Bolsonaro.

The Coordenação Anarquista Brasileira (Brazilian Anarchist Coordination) point out the geopolitical forces that lie behind his regime: “It’s clear our continent, Latin America, is seen as a strategic reserve of resources (political, natural, energy) for the use of the US, which makes the political situation of Brazil so important to Washington”.

Bolsonaro has followed the USA’s lead in declaring war on so-called “fake news”, which seems to mean any criticism of his policies by a supposedly “left-wing” media.

The UK government is also getting in on the censorship act, announcing that it is preparing to establish a new “internet regulator”.

Reports Buzzfeed: “The planned regulator would have powers to impose punitive sanctions on social media platforms that fail to remove terrorist content, child abuse images, or hate speech, as well as enforcing new regulations on non-illegal content and behaviour online”.

All of this helps further reduce what the Network for Police Monitoring (Netpol) recently called “the shrinking space for protest in the UK”.

Netpol’s Kevin Blowe wrote: “The militarised mentality of public order policing undoubtedly demands the latest technological advances, but it does so for a reason: conducting any war is never simply about the capture of physical space, but about the ability to maintain domination and control over it.

“’Keeping the peace’ (perhaps more accurately, pacification) involves the shrinking and ultimately denial of any space that your ‘enemy’ might conceivably benefit from. In public order policing terms, this invariably means any space to directly challenge either state or corporate power exercised in the name of progress or economic growth: for example, against the construction of airports, subsidies for the arms industry, nuclear power, fossil fuel extraction, or restrictions on workers’ rights”.

Netpol’s 2017 report on the policing of anti-fracking protests in England highlighted concerns that intense police surveillance of protesters has a potentially ‘chilling effect’ on freedom of assembly, in actively discouraging many from participation in campaigning activities.

“Furthermore, the smearing of legitimate campaigners as ‘extremists’ drives a wedge between them and potential allies in their communities and is used as a weapon against them by the media and pro-industry groups”, added Blowe.

Meanwhile, after the trial run with dogs, the microchipping of the UK’s human population is underway, starting at that point of greatest disempowerment, the workplace.

UK firm BioTeq has already fitted 150 implants in the UK. Another company, Biohax of Sweden, says it is in discussions with several British legal and financial firms about fitting their employees with microchips, including one major company with hundreds of thousands of employees.

If you can’t see the connection between this news and everything that has been outlined above, then you’re really not paying attention!

Work penetrates and determines the whole of our existence. Time flows mercilessly by as we shuttle back and forth between depressing and identical locations at ever-increasing speeds.

Working time… Productive time… Free time… Every one of our activities fits into its box. We think of acquiring knowledge as an investment for a future career; joy is transformed into entertainment and wallows in an orgy of consuming; our creativity is crammed within the narrow limits of productivity; our relationships, even our romantic encounters, speak the language of performance and profitability…

Our alienation has reached the point where we seek out any kind of work, even voluntary, to fill our existential void, to “do something”.

The identification of work with human activity, this doctrine which presents work as human beings’ natural destiny, seems to be lodged deep within our minds. This has reached the point where to refuse this forced condition, this social constraint, seems sacrilege, something no longer even thinkable.

Thus any kind of work becomes better than not working. That is the message spread by the defenders of the existing, those who want to maintain this world by calling for an ever-more frenetic race amongst the exploited, who are supposed to trample all over each other for a few crumbs from the bosses’ table.

However, it is not only the general working conditions that are leading us into this dead-end. It is work as a whole, work as a process which turns human activity into merchandise. It is work as a universal condition in which social relationships and ways of thinking are formatted.

It is work as the spinal column that holds together and perpetuates this society based on hierarchy, exploitation and oppression. And work as such must be destroyed.

We don’t just want to be happier slaves or better managers of our own misery. We want to restore meaning to human activity by acting together, guided by the quest for joie de vivre, knowledge, discovery, camaraderie and solidarity.

For individual and collective liberation, let’s liberate ourselves from work!

(Translated from anonymous leaflet Le travail libère-t-il?)

Residents of Whitehawk, a working-class district of Brighton, England, are battling to stop a new housing development being built over a designated local nature reserve.

Outraged by the plans before Brighton council, a hundred people packed into a church hall on November 12 and voted unanimously to call on the local authority to throw them out.

No political party has overall control of Brighton and Hove City Council, but Labour has the most councillors (22), with 20 Tories, 11 Greens and one independent.

A sign of the campaign’s momentum came four days after the public meeting, on November 16, when the East Brighton branch of the Labour Party unanimously called on all Labour councillors to oppose the development.

The housing scheme is being proposed by Hyde Housing, a business notorious for its profit-hungry approach.

It wants to build five blocks of flats on the local nature reserve at Whitehawk Hill, which is a common, Statutory Access land under the CROW Act and is an Ancient Neolithic Scheduled Monument.

An interesting side-issue has been the role played by something called Brighton Yimby, which claims to be a local pro-development group and announced online a “Whitehawk Says Yes” campaign in favour of the Hyde project.

An article on the Hands Off Our Sussex Countryside blog revealed that this “group” is “less grassroots and more astroturf”.

It seems to have very little support in Brighton itself, with the notable exception of local Tory politician Rico Wojtulewicz, who also happens to be the senior policy advisor for the House Builders Association (HBA), the housebuilding division of the National Federation of Builders.

Instead it is very much part of an international, mainly American, “Yimby” network described in one US article as “the darlings of the real estate industry”.

We can only assume that when BrightonYimby claimed to speak “for the interests of the many” it meant to say “money”.

An impressive series of infographics has been produced, showing the variety of complementary ideas challenging the global domination of industrial capitalism. The illustrations cover degrowth, ecofeminism, deglobalization, the commons, the Vivir Bien movement and the concept of the rights of Mother Earth. Importantly, all these perspectives are recognised as complementary and opening up the possibility of a different world. Says the website: “To build systemic alternatives it is necessary to forge strategies and proposals that at different levels confront capitalism, extractivism, productivism, patriarchy, plutocracy and anthropocentrism”.

* * *

A dynamic protest movement, NO TAP, has emerged in Melendugno, near Lecce in southern Italy, in response to the threat of the 540-mile Trans Adriatic Pipeline, due to bring gas from Azerbaijan into Europe via Turkey, Greece and Albania. Local anger was sparked in 2017 when the start of the works resulted in the uprooting of more than 200 olive trees and the creation of a securitised dead zone at the heart of the community. People have mobilised in numbers and have, inevitably, been met with repression by the police, those worldwide defenders of the industrial machine. NO TAP have produced a short video giving an idea of their full-on first year of struggle and which includes the following inspiring message: “The sun is shining for everyone, the wind is blowing for everyone… the possibility of realizing change is only a matter of will”.

* * *

A protest is to be staged against the Welsh government’s plan to build a new motorway across the Gwent Levels, to the south of Newport. It would cost taxpayers at least £1.5 billion and drive global warming, whilst destroying a landscape known for its wildlife, archaeology, tranquillity and beauty. Says the CALM campaign: “Join us to say #NoNewM4, 12.30pm, Tuesday 4th December, outside the Senedd, Cardiff Bay. Our rally is an urgent call for Wales to take a fresh path – fit for all of us today, and for all our future generations”.

* * *

Angry local people in eastern France are rising up against a hideous toll motorway project near Strasbourg, and some of them have been on hunger strike for a month. The 553-million Euro GCO scheme threatens many acres of forest and countryside and has been pushed through by the state and its corporate chums Vinci in spite of public inquiries coming out against it. Protesters have regularly blocked the work, causing serious delays in the project, and on November 18 some 400 people turned up to plant trees on the land already rased to make way for the new road. There is an international call-out to block Vinci everywhere in solidarity.

* * *

The week of action against the G20 and IMF in Argentina (see Acorn 44) begins on Monday November 26 and the full programme of events has now gone online, in English, here. A date to keep an eye open for is Friday November 30, which is a national day of struggle against capitalism.

* * *

We have come across two interesting online articles about that grim industrial-capitalist cult of life-denying artificiality known as transhumanism. Libby Emmons writes that “transhumanism is oppression disguised as liberation” and “part of a giant ideological redefinition of humanity”. She warns: “In its various forms, transhumanism is an attempt to reify an illusory mind-body dualism that has consequences well beyond what we can currently imagine”. And Julian Vigo comments on the dogmatic intolerance of the transhumanist stance, which paints as reactionary any point of view which questions, for instance, the wisdom of “cutting off healthy limbs to make way for a super-Olympian sportsperson”.

* * *

“Thames Valley Police sent in multiple riot vans, used force against protesters several times and stood by as the Union’s private security assaulted protesters in broad daylight. One of the main chants throughout the demonstration was ‘Who protects the fascists? Police protect the fascists!'” The reality of the way that the capitalist system promotes and protects the far right was once again exposed in Oxford, UK, this month, where Islamophobic American globe-trotter Steve Bannon was met by a hostile 1,000-strong crowd when he turned up at the university. Report here.

* * *

An exciting new step is being taken by the Enough is Enough project, which provides online news and info on the international struggle against capitalism, fascism and other forms of injustice. It is opening an info café in the Nordstadt district of Wuppertal, German territory. They say: “We do not just believe in a better world. We have started to live it a long time ago. And you all can decide if you want to become part of this world”. They have a crowdfunding site here.

* * *

Feral Crust is an eco-anarchist collective based in Davao, Philippines, which is working on a land and community project. It is set on 1/2 hectare (1 acre) of the hilly terrain within the remaining forests that is home to native wildlife and indigenous people. You can read about their bid for land regeneration and autonomy here.

* * *

In the midst of a devastating civil war, Kurds in Northern Syria, are building a multi-cultural society based on feminism, ecology, and direct democracy. How can these ideas lead to a lasting peace in the Middle East? What are their implications for radical politics in the West? What is it about the social structures of Rojava that inspires the fierce loyalty of its defenders and its people? Join Debbie Bookchin and David Graeber in London at the DJAM Lecture Theatre SOAS Russell Square Campus to discuss these issues Sunday November 25 from 5pm to 7pm at an event to launch the new publication Make Rojava Green Again by the Internationalist Commune in Rojava. The book will be available to buy and all proceeds from sales support the work of the Internationalist Commune. More information here.

* * *

Acorn quote: “This system cannot be reformed. It is based on the destruction of the earth and the exploitation of the people. There is no such thing as green capitalism, and marketing cutesy rainforest products will not bring back the ecosystems that capitalism must destroy to make its profits. This is why I believe that serious ecologists must be revolutionaries”.

Judi Bari (1949-1997)

(For many more like this, see the Winter Oak quotes for the day blog)

—–

If you like this bulletin please tell others about it. Subscribe by clicking the “follow” button.

—–

Back Issues

Follow Winter Oak on Twitter at @WinterOakPress