Interview with Mick Hume, British author and editor

By Milenko Srećković

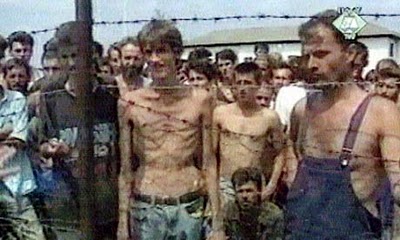

In 1997 British magazine “LM” published a translation of the article “The picture that fooled the world” by German journalist Thomas Deichmann, where the way in which big media corporation ITN reported on war in Bosnia in 1992 was called into question. In his article Deichmann concluded that ITN’s video record, where strikingly skinny Bosnian Muslim Fikret Alić stands behind barbed wire, was intentionally edited to remind the viewers of Nazi concentration camp. The picture of this malnourished man behind the wire went around the world, was published on the front pages of many world journals and, according to Deichmann, served to equate Serbs with Nazis in the mind of the readers, and to present the entire conflict in paradigmatic, black-and-white manner. Deichmann, by the way, had for the first time opportunity to see the whole unedited ITN’s recording in Hague, where he stayed in 1994 as expert witness before the war crimes tribunal.

ITN corporation denied Deichmann’s claim that it “intentionally” deceived the public by its way of reporting and filed a lawsuit for defamation against “LM” magazine. Since the magazine, not being able to prove the existence of “intent”, lost the trial, the amount of fine it had to pay led to its shutdown. Noam Chomsky has repeatedly pointed out this case as an example of the violation of the freedom of speech and characterized British legislation on defamation as “grotesque” and “absolutely horrible”.

After the shutdown of “LM”, its chief editor Mick Hume became the editor of internet magazine “Spiked“. His last book, “There Is No Such Thing As a Free Press – and we need one more than ever”, was praised by Daniel Finkelstein, the executive editor of “The Times”, as “a masterclass in the writing of polemic”. We spoke with Hume about how he looks at this case today.

– How did you feel after losing a libel suit brought by ITN and what that made you think about the freedom of expression in your country?

I was not surprised that we lost. We expected it, although our lawyer won every argument in court, because the UK libel laws are biased against defendants and freedom of expression. As I said to the media on the steps of the Royal Courts of Justice after the trial, “The only thing this case has proved ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ is that the libel laws are a menace to free speech and a disgrace to democracy.”

– What was the reaction of the public on the outcome of this court procedure.

We had a lot of support from people who understood and supported the two key principles we were fighting for. First, we were taking a stand for the historic right to freedom of expression. And second, we were challenging the idiotic idea that the Bosnian civil war could be compared to the Nazi Holocaust. That was a dangerous notion which could only diminish the horrors of the past, and distort the conflicts of the present. Without the support of those who sided with LM, we could not have fought the case at all.

But we were also bitterly opposed by other liberal intellectuals and journalists, who could not comprehend that we opposed their moral crusade to brand the Serbs as “the new Nazis”. They still cannot understand it and still despise our stand – even many of those who campaign to reform the UK libel laws will say it was right to sue LM! So our case was an important moment in dividing opinion.

– What is a freedom of expression for you, how much do people have it at this moment and what are the biggest current obstacles for it? What is the you-can’t-say-that culture?

I believe in freedom of expression for all, with no “ifs” or “buts”, as an indivisible right. Free speech is not something to be handed down like charity, only to those deemed to “deserve” it. We must defend it for all or none at all.

The you-can’t-say-that culture is something we criticise a lot on Spiked these days. It is a stifling atmosphere of conformism which dictates that any opinion deemed too offensive or “extreme” should be shut out of public debate. It is this sort of informal self-censorship which means that formal state censorship has rarely been needed to control debate in a society such as the UK. My view is the opposite: that if the believe in free speech, it is only really the alleged extreme or offensive views that need defending. Mainstream and conformist opinion can look after itself.

– Tell us more about your book There Is No Such Thing As a Free Press – and we need one more than ever. What do you think about the press in your country?

My book is really a response to the attempts to impose new restrictions on press freedom in Britain, around the Leveson Inquiry into the phone-hacking scandal. The fundamental myth here is that the press has been “too free” to cause trouble. My book argues that, on the contrary, the press is neither free nor open enough even before new regulations and restrictions are imposed. We need the spirit of the 45-word US First Amendment, which enshrines freedom of speech and of the press, not the million words deadweight of Lord Justice Leveson’s report which proposals ways to police those vital liberties.

There are many problems with the British press. But none of them will be addressed by making it even less free. I defend the right of the press to be an unruly, trouble-making mess. As Karl Marx said in defending press freedom against the Prussian censors 170 years ago, “You cannot grasp the roe without its thorns!”

– What do you think about continuing military interventions in the Middle East and could you compare it with the Yugoslavia civil war in the 90s?

I have always opposed Western intervention, whether political or military, and wherever it is aimed- from A for Afghanistan to Y for the former Yugoslavia. I oppose it in principle, as an attack on democratic right to self-determination. And I also oppose it on practical grounds – because it only ever makes matters worse for those on the receiving end. LM was never, as some claimed “pro-Serb” in the civil wars of the 1990s. We were anti-intervention, and opposed to all attempts to justify it by falsely branding the Serbs as the “new Nazis”.

I think Bosnia was a turning point. It was the moment when many who call themselves liberals in the UK and the West became the loudest champions of military intervention. We called them “laptop bombardiers”, demanding that the West make war on the Serbs in order to make them feel morally superior. There has been a strong pro-intervention climate in Western politics ever since. That is why, if somebody claims they are opposed to British intervention in, say, Syria today, I cannot take them seriously if they supported it in Bosnia.

– Tell us more about the progressive initiatives in your country that you support.

There is a distinct shortage of genuinely “progressive initiatives”in the UK today, unfortunately. I put my efforts into Spiked (spiked-online.com), the online polemical magazine which I helped launch, as editor, after LM magazine was closed by the costs of the libel trial in 2000. These days I am editor-at-large, with a backseat role. Spiked is a small but increasingly influential voice for freedom of speech and other humanist principles. It has big plans for fighting the free speech wars in the future – and for remembering those of the past. This is a link to my recent Spiked essay on the latest attempts by our opponents to re-run the LM libel trial – www.spiked-online.com/newsite/article/free_speech_war_II/14351#.UtlCqBDFLIU

FreedomFight.net