The attack against modernity is a cliche at this point. Even if once upon a time that critique was in the domain of reactionary intellectuals and apocalyptic sects, now it simply forms part of popular culture, embedded in movies, music, and video-games. Recently, I opened a book by Ernesto Sabato, a surrealist writer of the 50s. The first paragraphs describe a world where humans have turned into cogs of the capitalist machinery and slaves of instrumental reason. Although this proposition may have sounded very profound and original for the 1950s reader – it made me close the book. I didn’t stop reading because his viewpoint was incorrect or stupid, but simply because I would learn nothing from that book, for I have encountered that perspective throughout most of my life, through the internet, television, and contemporary thinkers.

However something that has been transformed into a permanent topic of conversation is trivialized, being converted into the unexamined chatter of “they”. The critique against technic and the enlightenment is not anymore a novel observation – not like it was in the first half of the 20th century, when it was first developed by Heidegger and the Frankfurt School. This position is simply a fossilized point within any superficially “anti-systemic” perspective, whether its from the far right or left, or from a popular music band. Given the state of this critique, it is necessary to re-analyze its premises, since its ossified form has led to the obliteration of the objects of criticism: namely the triumphs of the Enlightenment. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, since the merits of the Enlightenment were considered beyond questioning, it was necessary to excavate the dark side of the technic, that logic of scientific domination that has transformed human labor and the Earth into an accumulation of commodities Yet, once again, we must reconsider the successes of the Enlightenment in lieu of the dominance of anti-technic arguments.

To clarify the discussion I will briefly define what I mean by the technic. I do not refer to technology itself, given that it has existed in an artesanal form since before civilization. What I mean instead is a scientific-technical totality (both social and “instrumental”) used to abstract the universe into discrete entities that can be studied in a fundamental manner, entities subject to universal laws. The technic also facilitates the manipulation of entities through science and coordination for utilitarian ends (e.g. engineering, logistic, etc). This totality incorporates technology, but it cannot simply be reduced to the neutral application of science. We can locate the origin of this conception of the technic in the 17th century, with the Enlightenment and the thought of Newton and Descartes. The technic is not only used to understand and manipulate the natural world, but also society, through logistic, psychology, and coordination (e.g. marketing, industrial engineering, public administration).

I will not attack this anti-technic perspective in its totality, for I don’t think it’s completely flawed. Only a technocrat or white supremacist would have the guts to defend modernity like something completely positive. Modernity brought the holocaust, the atomic bomb, and the rape and pillage of the americas. Information technology has given rise to a state of surveillance that would kill of jealousy the secret police of Stalin and Hitler. The rationalization of the natural world so that it can be exploited by logistics and technics is leading to global warming, a process that would not only kill hundreds of thousands due to hurricanes and heat-waves, but would come with incalculable socio-economic devastation. There’s a reason why science fiction projects worlds of evil computers and ecological destruction – this recognition of the dark side of the technic is rooted in the marrow of western culture. Before the empirical evidence and sentiment of this era, it would be irresponsible to hide the crimes of our technical society. Finally, like Heidegger once argued, the technic has concealed that qualitative part of truth that is not quantifiable, such as the poetic dimension of a forest, or social structures that are invisible to calculation, but that still scaffold the power differentials between classes, races, genders, etc.

Many socialists of more positivistic nature would argue that this critique isn’t about the scientific-technical society, but about capitalism. They say that technology and science are neutral, and that they can be used for pro-social ends as much as for destructive ends. Science could be used for the good – for the construction of a sustainable world, with automatization and cybernetics applied for the emancipation of society from toil, hunger, and in a distant future, for the liberation of humanity from the limits of an organic and mortal body. But this viewpoint gives an ahistorical role to science that not even the old thinkers of the Enlightenment expounded. Science, as we understand it, is not simply a continuity that begins with the prehistoric origin of tools and human curiosity and ends in the present. Modern science emerged and evolved in combination with capitalist development. The technic as defined in the beginning of this essay, has only existed for a couple of centuries. In contrast to modernity, the technologies invented in more ancient epochs were not coupled with an all encompassing perspective that treats the universe like a machinery that can be manipulated for utilitarian ends, but simply emerged through trial and error. This conceptualization of the cosmos is linked with the abstraction of all social relationships, such as the transformation of peasants and artisans into an homogenous proletariat that can be subject to the coordination of a technical-logistic rationality. This rationality was described in the first chapter of “The Wealth of Nations” by Adam Smith. The destruction of the community and its organic unity and its replacement by price signals and coordination was not simply a neutral process of abstract problem solving, but the creation of an efficient machinery destined for capital valorization.

However, the various tendencies of the technic are not simple and unidirectional. Although critics attack the technic for its homogenizing violence, and its subsumption of the particular under the universal through the force of abstraction, since the technic privileges the “scientific” narrative over others (e.g. religion), these critics are victims of their own “post-structuralist” abstractions. A more rigorous and charitable analysis of the technic would see it as an unstable, contradictory system. The power of scientific-technical abstraction isn’t only used to convert humans and forests into piles of labor and lumber that can be dissected and manipulated. This tendency undoubtedly exists, and it represents a drive towards domination, but there are also emancipatory tendencies, both ideological and material. For example, the radical wing of Enlightenment, represented by the likes of Spinoza, considered the technic as an instrument for establishing a democratic and egalitarian society, a weapon against popes, kings, and lords.

Since the technic does not require divine revelation to be accessed – but simply uses the rational capacity of any human being – it becomes emancipatory. The physical laws of Newton and the geometry of Descartes, were discovered through calculation, abstraction, and analysis, which are mental capacities universal in all human beings (Kant); these discoveries weren’t revealed through divine revelation, such as the content of religious texts and the divine rights of kings. If all humans have the capacity for calculation and reason, and if the optimal social order can be excavated by the technic, in the same way engineering can be used to create the most optimal machinery, then the consequences of this argument is that all humans, with their autonomous reason, can participate in the political and social administration of the social order.

This defense of the technic outlined previously was of an ideological nature. However, there is also a material defense of the technic that was originally outlined by Marx, but that was then confirmed empirically by the trajectory of western europe. The rationalization of the european peasantry into free laborers that are not attached to the land, dissolved the agricultural patriarchy. Before, the peasantry was constrained by the land, the youth were completely submitted to the power of the parents and the feudal lord. Specifically, the youth had to inherit the land from their parents, and for marrying they required a dowry that also came from the parents, furthermore the youth had to swear fealty to feudal lords.

This emancipation of labor from the land also brought the structures that scaffold gender rights in modern liberal democracies, which while imperfect, were an advancement in western europe. This decline of the lords’ power, based on the increasing concentration of ex-peasants in the cities and towns, and the emergence of industrial capital, also caused the transference of power from rural areas to urban centers, were workers, embedded in the industrial infrastructure, became indispensable to the circuits of capital since the fixed capital of industrialists would lose value without the manipulation of workers. Since workers were embedded in the logistical mesh of the economy, they were able to acquire democratic rights since the workers turned indispensable (Endnotes). Furthermore, the historian Geoff Eley argued that the vigorous expansion of democratic rights at the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, was triggered by workers’ movements – movements that would have not emerged if the technic hadn’t transformed the peasantry into proletarians, since that rationalization integrated workers into the political and logistical meshes of the city.

All these tendencies, one in the direction of domination, and the other in the direction of liberty and democracy, do not converge in a common course but instead create instabilities. In physics, an instability means that a system can move in many directions, without the properties of the system revealing a favoritism for a particular trajectory. For example, in the case of a ball at the top of a perfectly symmetric hill, random perturbations like the wind can push the ball in any direction along three hundred thirty six degrees, with every trajectory equiprobable. In the technic the same instability exists. Some directions point towards democracy, enlightenment, a world of leisure, health and education. Other tendencies of the technic point to opposite directions, such as the surveillance state, scientific racism, the atomization of all communities, and the extermination of all life.

All these trajectories of the technic aren’t simply a function of something external, in accordance to what the positivists say when they qualify the technic like something neutral, but actually emerged from the internal dynamics of the system- a tendency towards calculation, universalism, and abstraction. But this negative narrative about the technic, that drive that brought the extermination of six million jews through industrial-scientific means, and is bringing about the cooking of the Earth, while accurate, is only one tendency amongst others that emerge from an instability. The same instability also brought the democratic rights of workers, the decline of child mortality, the haitian revolution, and the destruction of the agricultural patriarchy in europe, the latter a process that also brought gains in gender equality.

The technic has various potentialities, one that dominates and kills, and the other that illuminates and liberates. However, a society obsessed with the technic, such as modern capitalism, will always push that instability towards the trajectory of domination. Capitalism found a vehicle for its own manifestation in the technic, for a society organized by price signals will always tilt toward the violence of the calculation. The properties of the human being that cannot be abstracted into a number become unintelligible – such as social and psychological needs. The technocrat only sees GDP growth, and the boss can only calculate surplus value. This aspect of the technic that only sees in forests and human energy stores, was demonstrated by Heidegger, who argued that the technic obscures and blocks the other aspects of the truth that are not quantifiable. However, he forgot to add that this aspect of the technic is only one potentiality, that tendency embedded in capitalism, given that a society ruled by money, a quantitative substance, will only exploit a narrow calculus at the expense of other more holistic aspects of the technic that may have emancipatory qualities.

This deconstruction of the technic as a totalitarian force requires a socialist synthesis. Socialism is the descendant of Radical Enlightenment, that tendency toward a world where humanity uses reason to create a free and democratic society, where social needs are satisfied by the economic order. The highest manifestation of the socialist technic emerges in the planned economy, under a world workers’ republic. However, socialists also argue that not everything can be abstracted into numbers, for social and psychological needs are not entirely intelligible to calculus.

Marx had described this qualitative aspect of the technic, for the rationalization of the human being within a division of labor dissects the body and mind, turning them into something automatic and alienated. Therefore, a socialist synthesis, while using the technic to plan a rational economy, must also yield a specific magisterium to the more spiritual and qualitative aspects of the human being. For example, in capitalism, one of the main objectives of national policy is GDP growth. However, in a socialist society, growth of productivity and efficiency wouldn’t be a priority, for there would be other objectives related to the flourishing of human beings. Many of these objectives cannot be subsumed into equations and rational dissection, but requires a space outside the technic. Socialism should therefore be a synthesis where the technic enhances other more qualitative modes of life, instead of just subsuming them under quantitative abstraction.

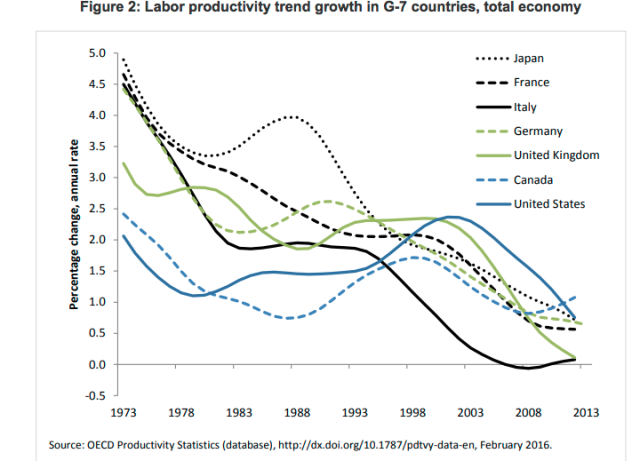

Source: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/wp22_baily-montalbano_final4.pdf

Source: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/wp22_baily-montalbano_final4.pdf Source:

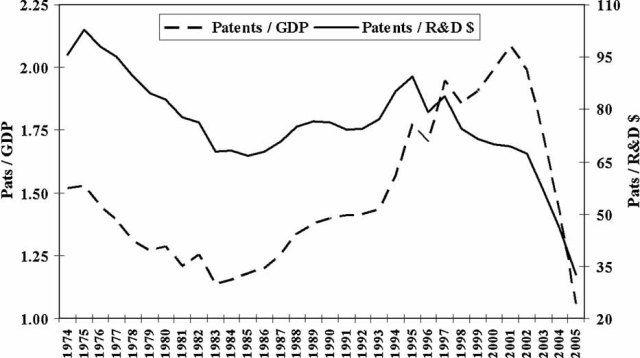

Source:  Source: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/sres.1057

Source: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/sres.1057

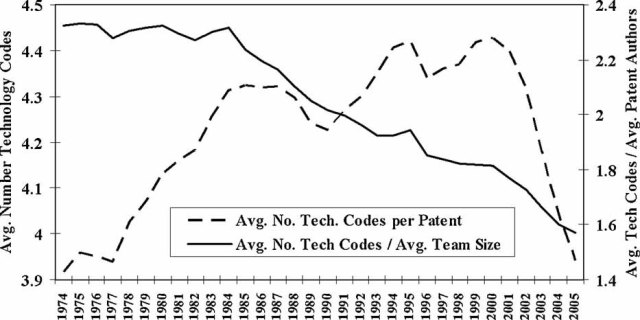

Source: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/cross-check/is-science-hitting-a-wall-part-1/

Source: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/cross-check/is-science-hitting-a-wall-part-1/