Below is my article reproduced from Overland Literary Journal, May 2018.

The Minister might not have intended his words to highlight the connections between colonisation and incarceration, enclosure and capitalism, the housing crisis and the state. Nor would he have wanted the house to be viewed as the outcome of unfree labour. Instead, it was an educational outcome and a housing outcome, and one that happily shifted attention away from the earlier news that inmates on similar incentives schemes were being paid as little as twenty cents an hour.

Ignoring for a moment that people should not have to be locked up to receive training, a house made with unfree labour and dressed up as self-improvement is not the first of its kind. In fact, if we lift the floorboards and peer a little deeper, the house that John Doe built reveals a long and hidden history of prison labour in New Zealand.

Although its use was never Imperial policy, as in Australia, prison labour weaves its way through almost every major urban centre and is entwined with many significant events in New Zealand’s past. Yet it is a history that is relatively unknown. An invisible history hidden in plain sight.

In August 1839, when discussing instructions from Lord Normanby on the annexation of New Zealand, Captain William Hobson asked for a supply of convicts from Sydney for use on roads and other public works. The Colonial Office turned down his request. But less than two years after the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi in 1840, prisoners were hard at work building the infrastructure of settler capitalism.

As Ben Schrader writes in The Big Smoke, the British had a long tradition of founding towns to impose control over new territories and Indigenous peoples. But the labour needed to build such towns was in short supply. Luckily, Hobson and his agents of empire were less interested in the use of hard labour within the confines of gaol than in the fact that they needed workers. There was far too much to be done on the ‘frontier’ to leave untapped labour within the hastily erected raupo huts that passed for New Zealand’s first prisons. With the formation of the Public Works Department still thirty years away, using forced labour on public works became the norm.

In Wellington in 1843, prisoners constructed Hill Street (alongside current-day Parliament Grounds), a waterfront road between the high water mark and neighbouring shops (in the area of Woodward Street). They laid drains in Manners Street and cut a road to Karori. Prison labour levelled the site of Terrace Gaol in 1851, built Cuba Street in 1856, and drained the Basin Reserve in the 1860s. From 1853, prison labour was used continuously on street works and public grounds around the burgeoning city. When they weren’t slogging through a ten-hour shift on roads, the incarcerated cut firewood to heat the buildings of government officials or crushed rock for more roads.

Like in Wellington, the spectacle of prison gangs being led daily through the streets of Auckland was a common occurrence in the early 1840s. Prison labour built Queen Street, Fort Street, High Street, Chancery Street and Victoria Street. Prisoners cleared land and built jetties on the shoreline. They were the main source of public works labour in Auckland until 1853, when outdoor work by prisoners was temporarily stopped.

Some of the hard-labour gangs were made up of the Parkhurst Boys, a group of 128 youths aged between twelve and twenty that had been transported from Britain to Auckland in 1842 and 1843. Gentleman settlers protested against ‘the inhuman attempt to convert our adopted colony into a pestilential convict colony’ and believed Auckland was becoming ‘the refuge for the juvenile delinquents of Great Britain.’ For the sympathetic, the sight of youngsters barely able to push a barrow load of metal was more worrying. The Sydney Morning Herald was aghast that boy labourers were ‘employed to break stones for little more than their food.’

Prison labour, including that of Māori prisoners of war, was essential to the development of Dunedin. Prisoners drained swamps, reclaimed harbours, deepened the berth alongside the Rattray Street jetty, built roads such as Cumberland and Castle Streets and roads on both sides of the harbour, and levelled entire hills. Rather than conforming to nature, settlers preferred to stick to the imposed grid of the surveyors. Bell Hill, which formed the Octagon in Dunedin’s city centre, was levelled by prisoners. One of them was the convicted arsonist Cyrus Hayley, who was shot dead while attempting to flee a Bell Hill work gang.

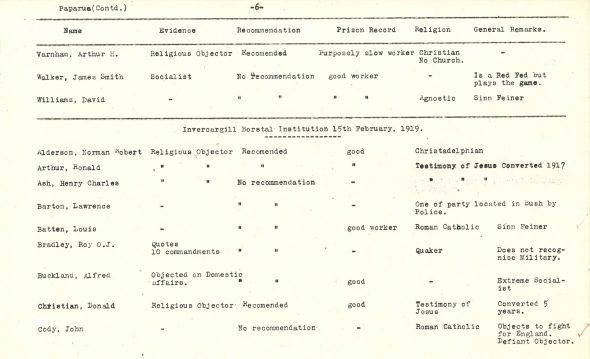

|

| Bell Hill, Dunedin. (1986/69/1, Otago Settlers Museum) |

All of this forced labour was cheap and convenient. But its use was as much about ideology as it was pragmatic. ‘Habits of industry’, industriousness and the work ethic were (and are) essential to the maintenance of capitalist social relations. Forced labour was a way to instil labour-discipline, just as prison training incentives today try to instil labour-discipline and readiness for the labour market upon release.

The idle and disorderly threatened such values, and whether inside a prison or not, had to be contained. Between 1868 and 1878 the number of people imprisoned rose from 3,292 to 4,924. In a time of increased mobility and unemployment, this itinerant prison force was overwhelmingly made up of people charged with vagrancy and other crimes of social control.

To make space for the growing prison population, some of the worst offenders were drafted out of jails and into great prison ships – called hulks – so they could be sent wherever work ‘of great public utility’ was needed. The practice of providing casual forced labour from mobile hulks was eventually abolished in 1891 (today, a not-dissimilar practice is known as ‘labour hire’).

By the 1880s, when prisons came under centralised administration, the state met the challenge of inadequate space by forcing prisoners to build the very walls around them. Prison labour was used to construct new prisons in Wellington, Christchurch, New Plymouth, Auckland, Dunedin, Greymouth, Whanganui, Napier, Invercargill, Gisborne, and various places in between. Many of these prisons were situated on land taken or questionably ‘purchased’ from Māori (the connection between public works and Māori dispossession needs no explanation).

By the late nineteenth century, the focus of building prisons meant there was often little prison labour to spare for other work. Despite this, working hours of 7.30am to 6pm in summer and 8am to 5pm in winter saw forced labour used on roads in Dunedin, Wellington, Hokitika and Nelson. Prisoners were put to work for local corporations and harbour boards at Invercargill, Timaru and Whanganui. In 1881, unfree labour built the breakwater at Ngamotu – the work gangs of prisoners transferred to New Plymouth for the job were marched to work under armed guard, and waited out the tides and bad weather locked behind bars in a cave at the base of one of the Sugarloaf Islands.

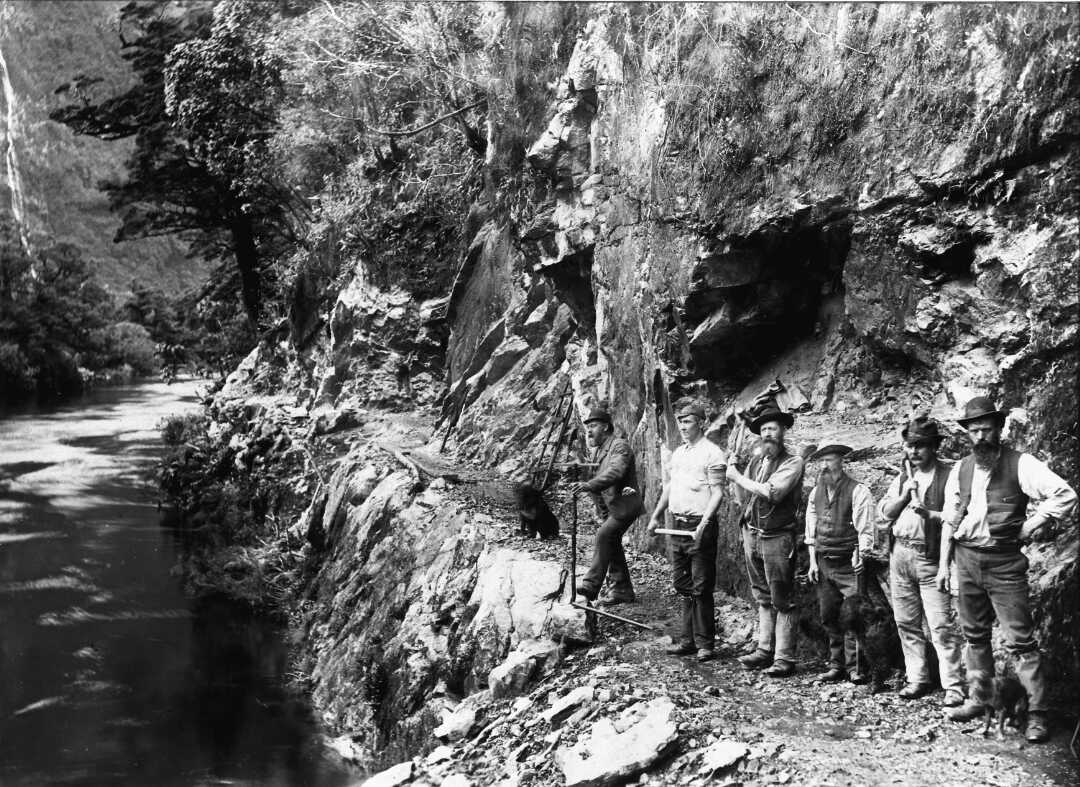

In this period, prisoners built the New Plymouth Hospital, the Addington Water Tower, the Hokitika Racecourse, a seawall in Nelson, Marine Parade in Napier, and attempted to forge a road through Milford Sound. Prison labour was also used for militarist and defence purposes, such as Dunedin’s Fort Taiaroa, Kau Point and Point Halswell in Wellington, and Ripapa Island in Lyttelton Harbour.

|

| Prison labour on the Milford Track (1/2-066563-F, Alexander Turnbull Library) |

During the First World War, resisters and conscientious objectors were herded into labour camps across the country and forced to build roads and bridges, or confined to state farms such as Weraroa, where generations of farmers before and since were taught the agricultural skills essential to the settler economy. Germans and other enemy aliens interned on Matiu Somes Island were forced to labour, violating the Hague Convention, while in Northland over 600 Dalmatians were forced into swamp drainage, railway construction and road-building, despite their willingness to serve in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force.

The Second World War re-established the use of objectors’ labour for the state, while at Featherston military camp, Japanese prisoners were put to work on state house chimneys and other tasks. On 25 February 1943, a group of about 240 staged a sit-down strike and refused to work. In the melee that followed, thirty-one Japanese were killed instantly, seventeen died later, and about seventy-four were wounded.

|

| Japanese prisoner of war making chimneys for state houses. (1/4-000779-F, Alexander Turnbull Library) |

Even the cherished dairy industry was tainted by prison labour. From 1909, prisoners were used to clear, break-in, and cultivate ‘waste’ land before it was subdivided into smaller holdings and sold to dairy farmers. By the 1930s, close to 27,000 acres of land had been cleared in the central North Island alone.

Underpinning it all was a gendered division of labour. It was women who did the invisible work that made the public work possible. Women made and mended clothes, washed laundry, sewed mattresses, repaired boots, scrubbed floors, baked bread, and completed a vast array of domestic duties. When they weren’t reproducing the labour power needed for public works, they picked oakum – the unravelling of old rope – for no other reason than to keep them working.

|

| Prisoners planting trees on the Hanmer Plains. (Christchurch City Libraries, PhotoCD 1, IMG0090) |

Officials in the 1840s and 1850s were dismayed by the number of prisoners in irons or solitary confinement for refusing to work. Seafarers and soldiers were especially unruly. Lieutenant Colonel C.E. Gold, commander of the 65th Regiment, complained in 1848 that many of his men preferred to be in gaol, where their subversion of discipline was more appealing than having to serve in the military.

In 1865, one woman inmate refused to work and threw her oakum ‘down the privy.’ After being punished for her ‘violent and insolent language,’ she was forced to retrieve the filth-covered rope and continue with her day’s quota.

In Kaingaroa, Paparua and Waikeria, First World War inmates went on hunger strike, refused to work or initiated go-slows to improve their plight. (At the time of writing, Waikeria was again in the spotlight for its disturbing conditions and confinement of inmates to their cells for up to twenty-two hours a day). Dalmatians downed tools at the Waihou River works, launched strikes on the Okahukura railway works, and refused to work the swamps near Kaitāia-Awanui. The man charged with their ‘care’, former Police Commissioner John Cullen, was upset at this work-refusal. Because Dalmatians had worked in wet and difficult conditions as gumdiggers, Cullen believed they would be happy to do forced labour on behalf of the state. He was wrong.

It has been said that the essence of imprisonment is organised compulsory work. It has also been said that capitalism is the subordination of all aspects of life to waged work. The connection between these two sides of the same coin – unfree and ‘free’ labour – is enclosure.

Enclosure is the ongoing process of divorcing people from their relationship with the land, from the commons, and from independent means of sustaining life. Enclosing bodies between prison walls is the ultimate expression of that process.

Even the rhetoric of prison rehabilitation cannot escape the connection, for the word ‘improve’, in its original sense, not only meant to make better but to do something for monetary profit. In particular, it meant to make land productive and profitable by enclosing it.

Enclosure and the violence of forced labour permeates the streets we walk every day and the public spaces we take for granted. It is a violence inseparable from colonisation and the dispossession that makes prisons and prison labour in New Zealand possible. For prisons were a Pākehā institution brought to these shores from without. And the use of unfree prison labour was there from the beginning.

In 1865, one woman inmate refused to work and threw her oakum ‘down the privy.’ After being punished for her ‘violent and insolent language,’ she was forced to retrieve the filth-covered rope and continue with her day’s quota.

In Kaingaroa, Paparua and Waikeria, First World War inmates went on hunger strike, refused to work or initiated go-slows to improve their plight. (At the time of writing, Waikeria was again in the spotlight for its disturbing conditions and confinement of inmates to their cells for up to twenty-two hours a day). Dalmatians downed tools at the Waihou River works, launched strikes on the Okahukura railway works, and refused to work the swamps near Kaitāia-Awanui. The man charged with their ‘care’, former Police Commissioner John Cullen, was upset at this work-refusal. Because Dalmatians had worked in wet and difficult conditions as gumdiggers, Cullen believed they would be happy to do forced labour on behalf of the state. He was wrong.

It has been said that the essence of imprisonment is organised compulsory work. It has also been said that capitalism is the subordination of all aspects of life to waged work. The connection between these two sides of the same coin – unfree and ‘free’ labour – is enclosure.

Enclosure is the ongoing process of divorcing people from their relationship with the land, from the commons, and from independent means of sustaining life. Enclosing bodies between prison walls is the ultimate expression of that process.

Even the rhetoric of prison rehabilitation cannot escape the connection, for the word ‘improve’, in its original sense, not only meant to make better but to do something for monetary profit. In particular, it meant to make land productive and profitable by enclosing it.

Enclosure and the violence of forced labour permeates the streets we walk every day and the public spaces we take for granted. It is a violence inseparable from colonisation and the dispossession that makes prisons and prison labour in New Zealand possible. For prisons were a Pākehā institution brought to these shores from without. And the use of unfree prison labour was there from the beginning.

First published by Overland Literary Journal, May 2018.