The first thing to understand about the decision by a federal judge to approve AT&T’s acquisition of Time Warner, over the objection of the U.S. Department of Justice, is that it is very much in-line with the status quo: this is a vertical merger, and both the Department of Justice and the courts have defaulted towards approving such mergers for decades.1

Second, that there is an explosion of merger activity in and between the television production and distribution space is hardly a surprise: the Multichannel Video Programming Distributor (MVPD) business — that is, television distributed by cable, broadband, or satellite — has been shrinking for years now, and in a world where the addressable market is decreasing, the only avenues for growth are winning share from competitors, acquiring competitors, or vertically integrating.

Third, that last paragraph overstates the industry’s travails, at least in terms of television distribution, because most TV distributors are also internet service providers (ISPs), which means they are getting paid by consumers using the services disrupting MVPDs, including Netflix, Google, Facebook, and the Internet generally.

What was both unsurprising and yet odd about this case was the degree to which it was fought over point number two, with minimal acknowledgement of point number three. That is, it seems clear to me that AT&T made this acquisition with an eye on point number three, yet the government’s case was predicated on point number two; to that end, the government, in my eyes, rightly lost given the case they made. Whether they should have lost a better case is another question entirely.

Why AT&T Bought Time Warner

What is the point of a merger, instead of a contract? This is a question that always looms large in any acquisition, particularly one of this size: AT&T is paying $85 billion for Time Warner, and that’s an awfully steep price to simply hang out with movie stars.

The standard explanation for most mergers is “synergies”, the idea that there are significant cost savings from combining the operations of two companies; the reason this explanation is popular is because saving money is not an issue for antitrust, while the corresponding possibility — charging higher prices by achieving a stronger market position through consolidation — is. Such an explanation, though, is usually applied in the case of a horizontal merger, not a vertical one like AT&T and Time Warner.

To that end, AT&T was remarkably honest in its press release announcing the merger back in 2016:2

“With great content, you can build truly differentiated video services, whether it’s traditional TV, OTT or mobile. Our TV, mobile and broadband distribution and direct customer relationships provide unique insights from which we can offer addressable advertising and better tailor content,” [AT&T CEO Randall] Stephenson said. “It’s an integrated approach and we believe it’s the model that wins over time…

AT&T expects the deal to be accretive in the first year after close on both an adjusted EPS and free cash flow per share basis…Additionally, AT&T expects the deal to improve its dividend coverage and enhance its revenue and earnings growth profile.

Start with the second point: as I noted at the time, it’s not very sexy, but it matters to AT&T, a 34-year member of the Dividend Aristocrats, that is, a company in the S&P 500 that raised its dividend for 25 years straight or more. It’s a core part of AT&T’s valuation, but the company’s free cash flow has been struggling to keep up with its rising dividends. Time Warner will help significantly in this regard, as did the previous acquisition of DirecTV.

It is the first point, though, that is pertinent to this analysis: how exactly might Time Warner allow AT&T to “build truly differentiated video services”?

The Government’s Case

While the AT&T press release noted that those “truly differentiated video services” could be delivered via traditional TV, OTT, or mobile, the government’s case was entirely concerned with traditional TV. The original complaint stated:

Were this merger allowed to proceed, the newly combined firm likely would — just as AT&T/DirecTV has already predicted — use its control of Time Warner’s popular programming as a weapon to harm competition. AT&T/DirecTV would hinder its rivals by forcing them to pay hundreds of millions of dollars more per year for Time Warner’s networks, and it would use its increased power to slow the industry’s transition to new and exciting video distribution models that provide greater choice for consumers. The proposed merger would result in fewer innovative offerings and higher bills for American families.

The idea is that AT&T could leverage its ownership of DirecTV to demand higher prices for Turner networks from other MVPDs, because if the MVPDs refused to pay customers would be driven to switch to DirectTV. The problem is that, as was easily calculable, this makes no economic sense: the amount of money AT&T would lose by blacking out Turner would almost certainly outweigh whatever gains it might accrue. The judge agreed, and that was that.

AT&T’s Real Goals

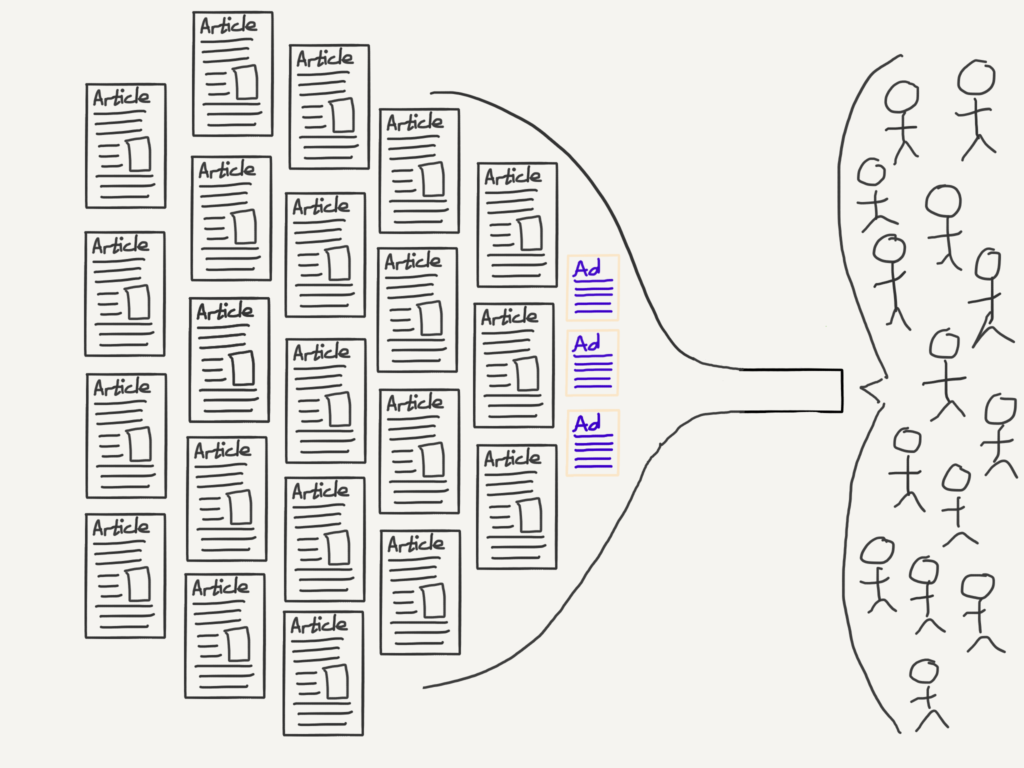

Remember, though, that AT&T did not limit its options to traditional TV: what is far more compelling are the possibilities Time Warner content presents for OTT and mobile. The question is not what AT&T can do to increase the revenue potential of Time Warner content (which was the government’s focus), but rather what Time Warner content can do to increase the potential of AT&T’s services, particularly mobile.

Forgive the long excerpt, but I covered this angle at length in a Daily Update when the deal was announced:

AT&T’s core wireless business is competing in a saturated market with few growth prospects. Apple’s gift to the wireless industry of customers demanding high-priced data plans has largely run its course, with AT&T perhaps the biggest winner: the company acquired significant market share even as it increased its average revenue per user for nearly a decade, primarily thanks to the iPhone. Now, though, most everyone has a smartphone and, more pertinently, a data plan…

The implication of a saturated market is that growth is increasingly zero sum, which presents both a problem and an opportunity for AT&T. The problem is primarily T-Mobile: fueled by the massive break-up fee paid by AT&T for the aforementioned failed acquisition, T-Mobile has embarked on an all-out assault against the incumbent wireless carriers, and AT&T has felt the pain the most, recording a negative net change in postpaid wireless customers for eight straight quarters. Unable or unwilling to compete with T-Mobile on price, AT&T needs a differentiator, ideally one that will not only forestall losses but actually lead to gains.

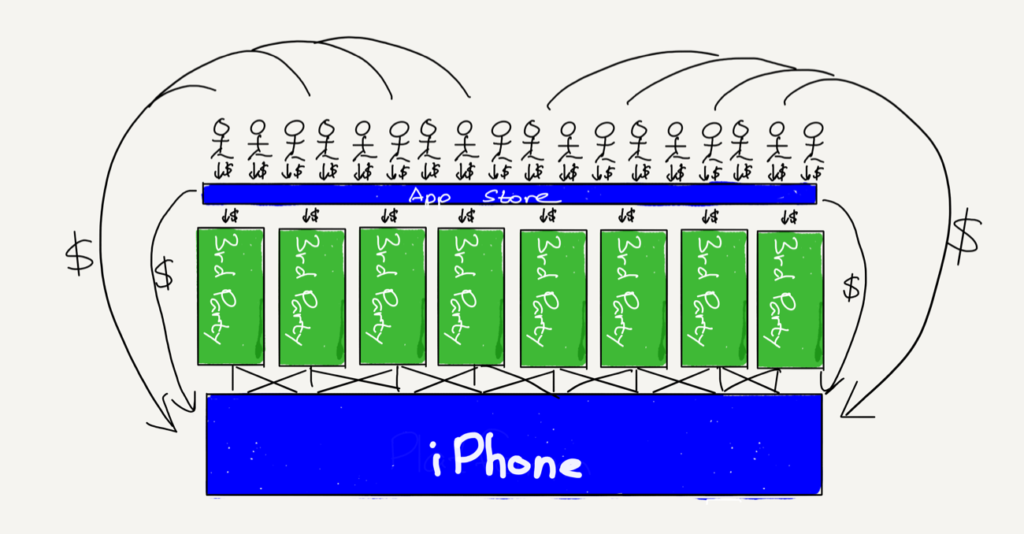

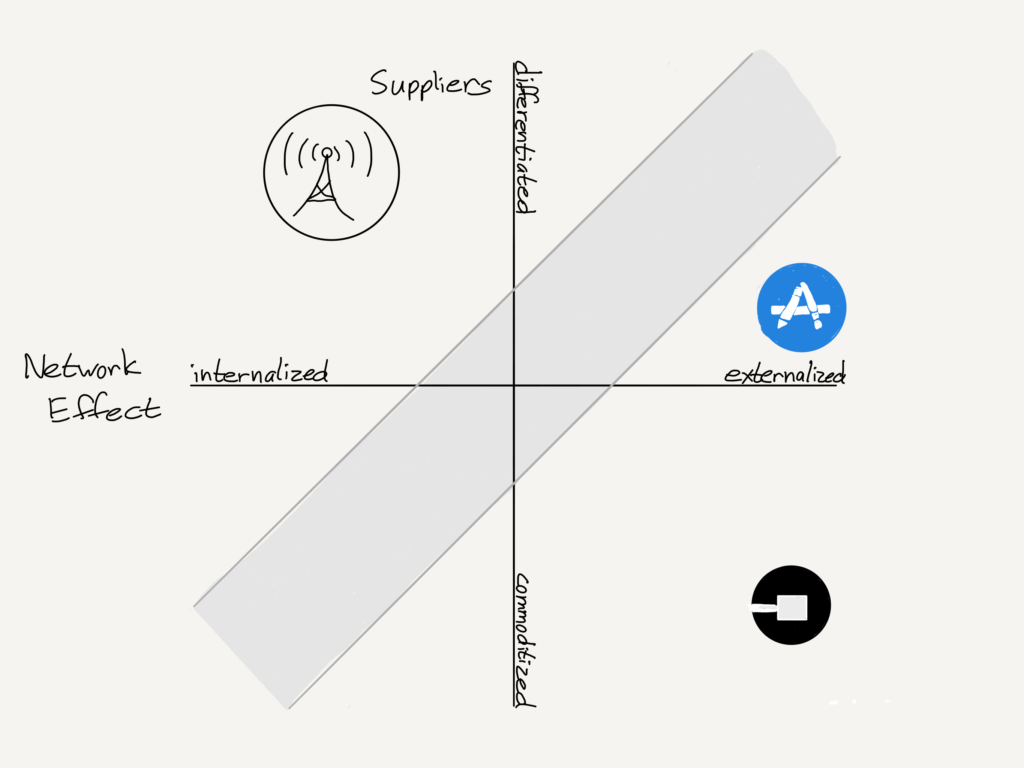

At first glance this doesn’t explain the Time Warner acquisition either: per my point above these are two very different companies with two very different strategic views of content. A distributor in a zero-sum competition for subscribers (like AT&T) has a vertical business model: ideally there should be services and content that are exclusive to the distributor, thus securing customers. Time Warner, though, is a content company, which means it has a horizontal business model: content is made once and then monetized across the broadest set of potential customers possible, taking advantage of content’s zero marginal cost. The assumption of this sort of horizontal business model underlay Time Warner’s valuation; to suddenly make Time Warner’s content exclusive to AT&T would be massively value destructive (this is a reality often missed by suggestions that Apple, for example, should acquire content companies to differentiate its hardware).

AT&T, however, may have found a loophole: zero rating. Zero rating is often conflated with net neutrality, but unlike the latter, zero rating does not entail the discriminatory treatment of data; it just means that some data is free (sure, this is a violation of the idea of net neutrality, but this is why I was critical of the narrow focus on discriminatory treatment of data by net neutrality advocates). AT&T is already using zero rating to push DirecTV:

This is almost certainly the plan for Time Warner content as well: sure, it will continue to be available on all distributors, but if you subscribe to AT&T you can watch as much as you want for free; moreover, this offering is one that is strengthened by secular trends towards cord-cutting and mobile-only video consumption. If those trends continue on their current path AT&T will not only strengthen the moat of its wireless service against T-Mobile but maybe even start to steal share.

That this point never came up in the government’s case, and, by extension, the judge’s ruling, is truly astounding.

That noted, it is very fair to wonder why exactly the Department of Justice sued to block this acquisition: President Trump was very outspoken in his opposition to this deal and even more outspoken in his antipathy towards Time Warner-owned CNN. At the same time, Makan Delrahim, the Assistant Attorney General for Antitrust who led the case, didn’t see a problem with the merger before his appointment. That the government’s complaint rested on both the most obvious angle and, from AT&T’s perspective, the least important, suggests a paucity of rigor in the prosecution of this case; it is very reasonable to wonder if the order to oppose the merger came from the top, and that the easiest case was the obvious out.

The Neutrality Solution

Thus we are in the unfortunate scenario where a bad case by the government has led to, at best, a merger that was never examined for its truly anti-competitive elements, and at worst, bad law that will open the door for similar tie-ups. To be sure, it is not at all clear that the government would have won had they focused on zero rating: there is an obvious consumer benefit to the concept — that is why T-Mobile leveraged it to such great effect! — and the burden would have been on the government to show that the harm was greater.

The bigger issue, though, is the degree to which laws surrounding such issues are woefully out-of-date. Last fall I argued that Title II was the wrong framework to enforce net neutrality, even though net neutrality is a concept I absolutely support; I came to that position in part because zero rating was barely covered by the FCC’s action.3

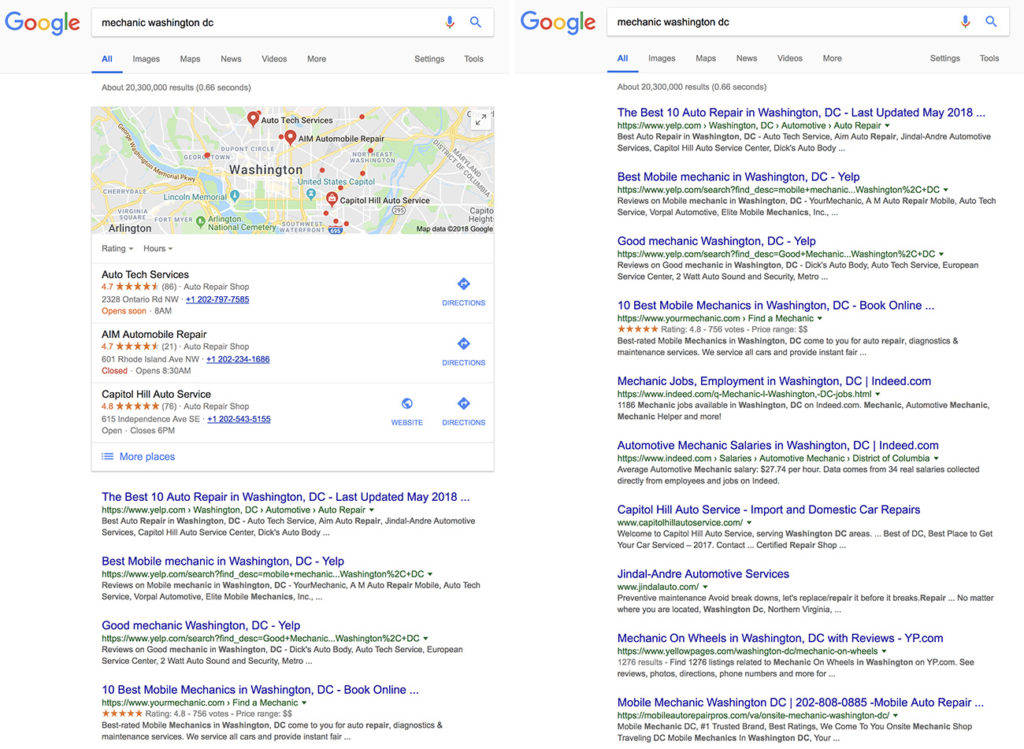

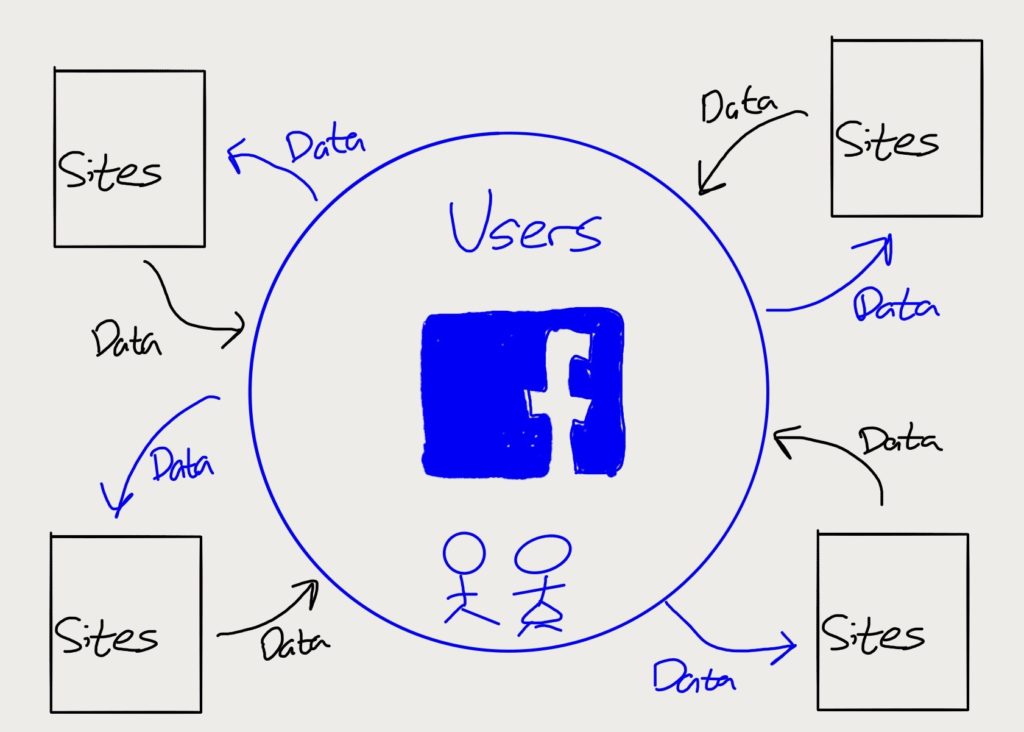

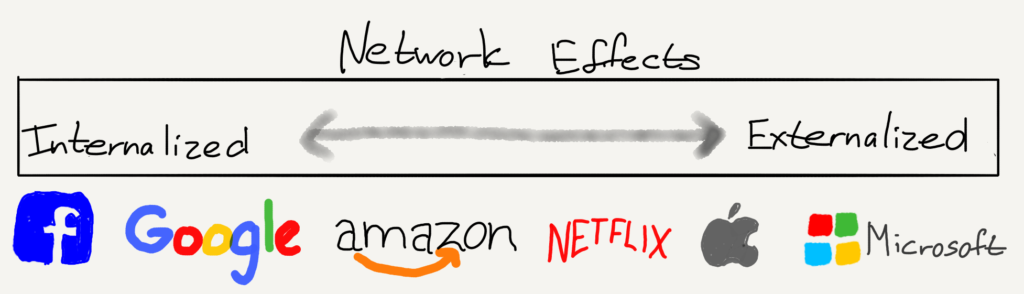

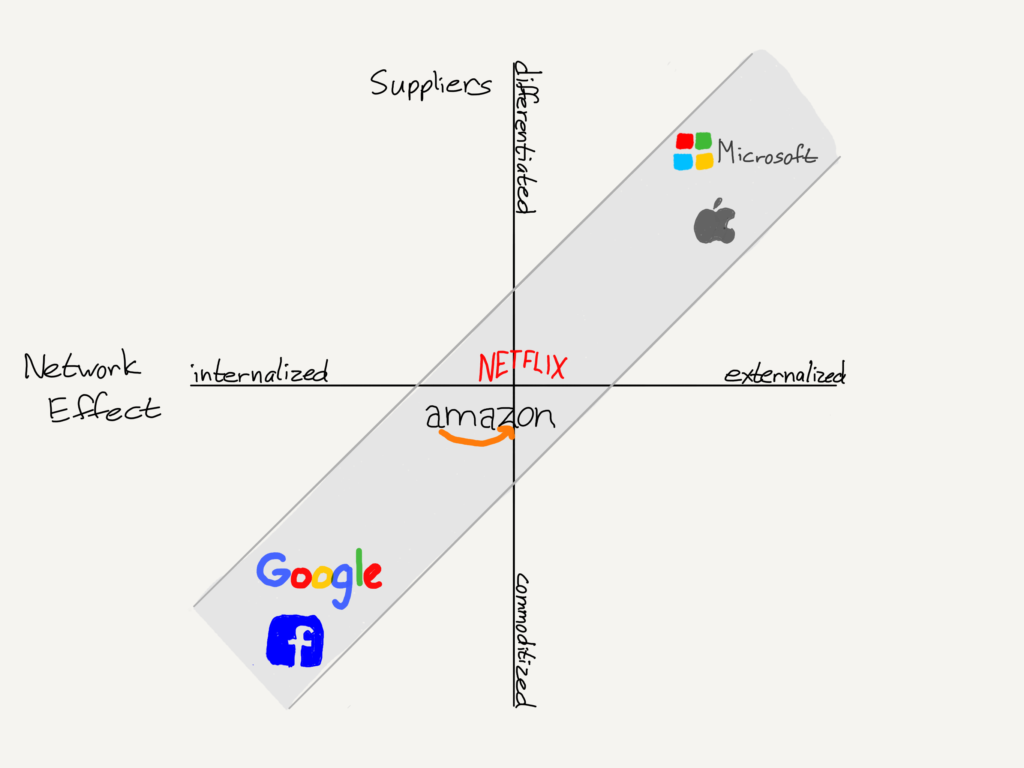

What is clearly needed is new legislation, not an attempt to misapply ancient regulation in a way that is trivially reversible. Moreover, AT&T has a point that online services like Google and Facebook are legitimate competitors, particularly for ad dollars; said regulation should address the entire sector. To that end I would focus on three key principles:

- First, ISPs should not purposely slow or block data on a discriminatory basis. I am not necessarily opposed to the concept of “fast lanes”, as I believe that offers significant potential for innovative services, although I recognize the arguments against them; it should be non-negotiable, though, that ISPs cannot purposely disfavor certain types of content.

- Second, and similarly, dominant internet platforms should not be allowed to block any legal content from their services. At the same time, services should have discretion in monetization and algorithms; that anyone should be able to put content on YouTube, for example, does not mean that one has a right to have Google monetize it on their behalf, or surface it to people not looking for it.

- Third, ISPs should not be allowed to zero-rate their own content, and platforms should not be allowed to prioritize their own content in their algorithms. Granted, this may be a bit extreme; at a minimum there should be strict rules and transparency around transfer pricing and a guarantee that the same rates are allowed to competitive services and content.

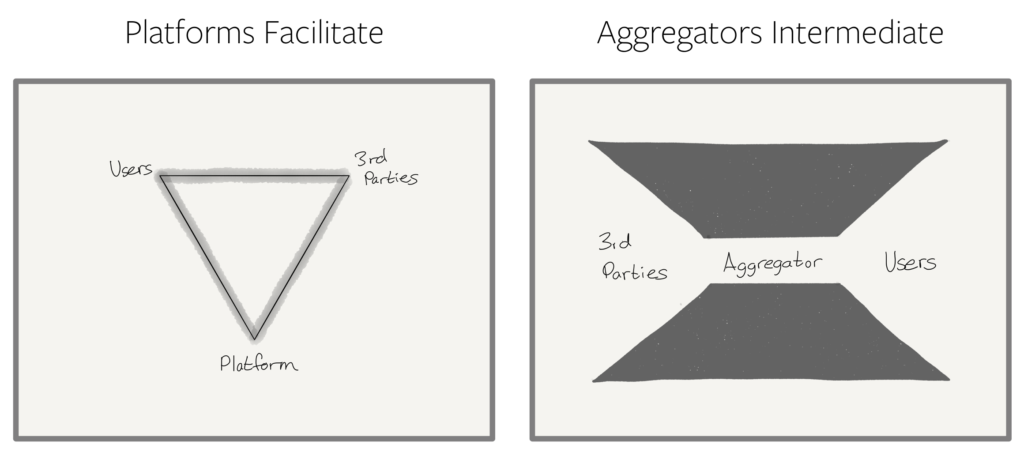

The reality of the Internet, as noted by Aggregation Theory, is increased centralization; meanwhile, the impact on the Internet on traditional media is an inexorable drive towards consolidation. Our current laws and antitrust jurisprudence are woefully unprepared to deal with this reality, and a new law guaranteeing neutrality is the best solution.

- Whether or not the presumption that vertical mergers are not anti-competitive is a worthwhile, albeit separate, discussion [↩︎]

- To be fair, the company also mentioned synergies, but it was hardly the point of the press release. [↩︎]

- The FCC said it would take it case-by-case, and did argue in the waning days of the Obama administration that zero rating one’s own services as AT&T is clearly trying to do was a violation, but that was never tested in court and was quickly rolled back [↩︎]