EXTRACT

Life With A Porn Queen

Chapter 9 (The Book of Strangers) of Maurice Suckling's debut novel, original Ink Monkey release

I’ve got an aisle seat. To one side is where Felix was supposed to be. To the other side is a tanned blonde girl in a short-sleeved black blouse with huge breasts. She’s reading the in-flight entertainment guide as the air stewardess pulls her drinks trolley alongside, leans in and mouths some words to her. She hands over an empty 250cl plastic water bottle. The stewardess fills it with glugs of water from a 2 litre bottle. Now the air stewardess is mouthing words to me. I’m listening to music on the in-flight entertainment system. I debate the free drink again, then tell her I’m fine. If I drink now then I’m A Drinker. I can’t tell myself it’s just social. I could have one. But one always leads to one more.

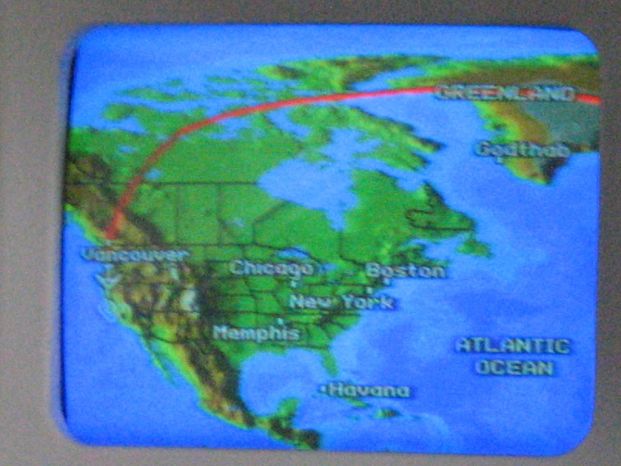

The iMap shows we’re approaching Newfoundland. I look back down at my notebook, where I’m drawing a stickman character surfing on the bottom right hand corner, so it looks like a flicker-book when I zip through the pages quick enough; makes it look like he’s skimming off the top of a wave, jumping off his board, and re-landing on it.

‘Anything to drink, madam?’ The air stewardess has brought her drinks trolley again.

The girl next to me hands over her empty 250cl plastic bottle. The stewardess fills it again with water from a 2 litre bottle.

‘Anything for you, sir?’

‘No thanks,’ I say.

‘You should have something,’ the girl says. ‘He should have something,’ she’s saying to the stewardess. ‘You should have something,’ she’s saying back to me. ‘Have some water — why don’t you have some water?’

‘Ok,’ I say, feeling like I’m being somehow lapped in the conversation and feeling the need to catch up, or stop the race completely. ‘Yes, why not?’ I look at the stewardess. ‘Some water please?’ She glugs some water from the same 2 litre bottle into a small plastic cup.’

‘Ice?’

‘Yes please.’

She uses small metal tongs, plops the large hollowing cylinder of ice into the cup and hands it over.

I nod my thanks and take a sip, putting the cup into the small circular indent in the tray table, which must only create a lip of a couple of millimetres.

‘Do you know how easy it is to get dehydrated on planes?’ says the girl next to me. I still have water trickling down my throat.

‘Back on earth,’ she’s saying, ‘we’re used to around 50% humidity — the air’s half saturated with water molecules. Do you know what the humidity is in this cabin?’

I slowly shake my head. Then I’m suddenly aware I should be saying something.

‘No,’ I say.

‘Between 1% and 5%,’ she says. ‘You should be drinking around 250cl an hour.’

‘But did you know you can drown by drinking too much water?’ I say, picking up my cup again without really meaning to, my hand just doing it on its own.

‘You dilute the salt so your cells drown,’ she says, folding her arms over her chest which I’m not looking at, and leaning ever so slightly back in her seat, ‘but it’s not like asphyxia. You can probably drink around 15 litres a day without it being dangerous.’

‘Are you a doctor, or something?’ I smile.

‘No,’ she says, ‘just interested in stuff.’

‘Ah, right,’ I say, and we look at each other for a moment and I wonder if she wants to talk, if I want to talk, if she wants me to think she wants to talk, if I should say something, what I should say if I did say something. She starts to turn away, back to the little black Kindle on her lap.

‘Did you know they’ve made a car in Japan that just runs on water?’ I say. She looks up, her mouth closed and her eyebrows slightly raised. ‘A generator separates the hydrogen and the electrons power the car,’ I tell her.

Her face makes a yeah, knew that, expression. ‘Did you know about 20 years ago a Bolivian inventor did the same thing, getting it to run off sea water?’

‘I didn’t know that,’ I say. ‘But did you know, on a litre of water the Japanese car goes at 80kmh for an hour?’

‘I didn’t know that,’ she says, ‘that is interesting stuff, thank you.’

‘Well,’ I say, feeling uneasy at the sudden shift in the rhythm in the conversation, ‘that’s ok..., I just...’

‘But did you know,’ she says, leaning forward, ‘the first electric cars were built in the 1830s, and they also had steam built cars till the 1930s?’

‘Yes,’ I say, ‘I did know that. And did you know if you drive at 55mph for just over 53 hours non-stop you’ll cover the distance from New York to San Francisco — which is 2,929 miles?’

‘Is that what you plan to do when you land?’ she says, turning her neck so her face is looking straight at me.

‘No,’ I smile, ‘I’ll drive for about 6 hours a day — so I’ll do it in about 10 days.’

‘Oh, ok,’ she says, then scrunches her brow and leans forward a little more. ‘What for?’

‘You know...’ I shrug my shoulders.

‘You do know the chances are it’ll be butt-numbingly boring, and all you’ll see is mile after mile of road, don’t you?’

‘Maybe,’ I say. ‘But I plan on taking my time a little, so maybe I’ll be lucky and get the full road trip experience.’

‘Ah, I geddit,’ she says, closing her Kindle and slipping it into the seat pocket in front of her. ‘So, the idea is, you see a few sights and meet a colourful cast of eccentrics and ultimately come to learn that the destination isn’t the point, it’s the journey itself, and the thing you were looking for was inside you all along?’

‘Ha,’ I say. ‘Something like that.’

‘Something like that,’ she says, like the echo’s an underline of what I said.

‘More or less,’ she says, more like her own voice.

‘So come on,’ I grin, ‘let’s hear it. If you know exactly how it goes, who do I meet?’

A grin pulls her face to one side.

‘You wanna know?’

‘Sure.’ I’m expecting her to tell me she’s just messing, or something.

‘So,’ she sits forward, both knees together, elbows on her thighs, ‘let me see... there’s the ex-KGB agent you meet when you rent the car in New York, who tells you, as a matter of pride, none of his fleet are bugged, and insists you check in all the obvious places every time you come back to your car, even if you’ve only left it for 5 minutes. Then, after that, you see a white van in New Jersey with OBAMA SAVES graffitied on the side. In West Virginia there’s the redneck mechanic — in the small town where you stop for lunch — who dresses like a Buddhist and fixes the rattle in the exhaust just by touching it, closing his eyes and mumbling something. In the roadside café in Kentucky you see a coachload of French Canadians with ice skates round their neck touring the Sopranos on Ice.’

‘You sure I don’t meet anyone on the road?’ I say. ‘No cute girls with a breakdown or anything?’

‘You do meet someone with a breakdown,’ she says. ‘In fact a blown tyre, and you help her with her spare. She’s just out of drama college and on her way to Hollywood with a tank of gas and 80 bucks in her purse. That’s in Missouri.’ She beams up at me and takes another breath.

‘Then in Kansas you pass a trucker with a Bin Laden mannequin tied to the front of his cab, like it’s a moose he’s shot. Then in Nebraska there’s a milf at the motel’s front desk with the drunk for a husband who offers you a 50% discount if you leave your door on the latch. Then at the breakfast bar in a roadside café in Colorado, you get talking to a drifter ex-scientist in a long hobo coat, who tells you he knows what the government’s been doing with the UFOs since the ’50s, so he’s on the run from the FBI.’

‘That it?’ I say. ‘Or does something happen in pretty much every State?’

‘You know what?’ she says, ‘something does happen in pretty much every State. There’s also the Mormon hitchhiker you pick up in Utah who you suspect has just robbed a bank and has the cash in the black bag on his lap. And of course, how could we forget the mute cowboy who works at the gas station in the middle of Nowhere, Nevada, you think is trying to warn you you’re in danger up ahead?’

‘How could we forget?’ I say.

‘So was that the kind of trip you had in mind?’ Her head’s tilted to one side, like butter wouldn’t melt.

‘Something like that,’ I grin because this girl is killing me.

‘But there was more, wasn’t there,’ she pushes at my knee with the flat of a small hand.

‘Not really,’ I say.

‘Yeah there was,’ she’s trying to tease it out of me. She bites at her bottom lip and pushes my knee again. ‘Go on! What happens when you get there?’

‘Get where?’

‘What happens when you get to San Francisco?’ She pushes my knee for a third time.

‘When I hit the coast I become a barman, and just surf.’

‘Surf?’

‘Yeah, you know, just surf — head out in the morning and live one day and...’

‘...one wave at a time?’ she says, finishing my sentence word for word, and I’m suddenly deeply uneasy about all of this.

‘Then,’ she continues, ‘maybe you could save up some money, maybe head up north, and live in a shack by the ocean away from consumerism and live close to nature?’

I have the sensation my mouth is making an O shape. I close it.

‘Is that about right?’ she says.

I scratch my chin, though I don’t have an itch.

‘Here’s the thing,’ I say, and I look quickly at her face, then switch my look to the blank screen on the back of the seat in front of me, ‘a few months back I got rid of all my possessions.’

‘Why would you do that?’ she says, but I don’t mind the question. I think I even want her to ask. I think I want someone who doesn’t know me to ask. That way I can try out the answer I’ve been working on.

‘I needed to feel different,’ I say. ‘I didn’t want to feel the same anymore. I was in a rut and I tried to get un-stuck.’

‘So how did that go?’ she says, I can feel her big blue eyes shining big blue beams into me.

I nod. ‘For a few weeks it felt quite good — I felt lighter. But, deep down, it didn’t make me feel any different. So...’ I look up for a moment, and she’s there listening to me, so I carry on. ‘I left work, but that just felt predictable and obvious and made me feel worse than before. So...’ I lean back in my seat, and stretch my arms behind my head like I’m yawning, and she’s still listening. ‘I left England and went to live in an old farmhouse in Normandy — but that didn’t work either. Now I think about it, that just felt predictable too. Just another dead end. No matter what I do, nothing really makes me feel any different. Everything just pauses the same feeling, but never gets rid of it. Everything’s just a temporary hiatus. There’s nothing I can do that makes me feel genuinely different.’

‘You know the coast to coast trip is going to be just the same, don’t you?’ she says.

I get a stopped-time feeling. The background hum of the cabin seems stuck on a loop.

I look at my feet; my black socks knocking into the metal bar looping around the seat in front of me.

‘Ok then,’ I look up, look straight back at her. ‘So what do I do?’

She holds my gaze and doesn’t blink.

‘Don’t do it.’ She’s sitting there with a fixed, calm expression, as if there is nothing easier, nothing simpler.

Alright,’ I say, humouring her, ‘then what do I do instead?’

She moves a little nearer to me, and pushes some too-blonde hair back away from her face.

‘Allow me to diagnose your problem,’ she says, fixing me with her big blue headlights. ‘You’ve got Story Over-Exposure.’

‘I’ve got what?’ Because I really don’t know what she’s talking about.

‘Story Over-Exposure.’

I’m looking at the plumpness of her lips, waiting for this to make sense.

Her face twitches and she touches my knee.

‘Gonzo or regular?’ she says.

‘Huh?’

‘Gonzo or regular? Don’t be coy... how’d you like your porn? With stories, or without?’

‘I dunno,’ I say, ‘I don’t know what you’re...’

‘Let me tell you what I think, if that’s ok with you,’ touching my knee again with the tips of a finger. ‘I think you find the stories pointless, and I think that’s because you need more from them.’

‘Do I?’ I look up to catch her expression.

‘You know how stories work,’ she nods, ‘so everything you can project for your life, every course of action, no matter how big and significant it feels, will always end up turning into a story you already know the ending of — right?’

I don’t say anything. I just make a face, and then, making it seem like I’ve processed a thought, I say: ‘Go on.’

‘Do you know how many stories our generation consume in a lifetime?’

I’m trying to work through an answer and she carries on.

‘Tens of thousands! A movie a day for twenty years is over seven thousand. You’ve watched, heard, and read so many stories this means you’re starting to disengage from them because they don’t surprise you anymore.’ She rubs at the underside of her red sofa bottom lip with a turquoise bitch-tipped finger.

‘So — you need a story that does surprise you. You need a new kind of story for your life.’

I look at her. Blink once, then look away, back at the blank screen in front of me.

‘And how do I get one of those?’ I grin and spin my eyes back to her.

‘Let me tell you a story,’ she says, sitting back a little, with a smirk on her bottom lip like her finger had put it there moments earlier ready to use it now.

‘It’s about a man whose life has ceased to surprise him.’

‘Yeah?’ I say.

‘Everything that happens to him feels like it’s happened to him before. And everything he thinks about feels like it’s something he’s already thought about. Nothing feels new. He tries various ways to address this, he takes up new hobbies, watches movies he would never normally see, he dyes his hair outrageous colours, he wears clothes he’s never worn before, goes to countries he’s never been to before, he leaves his girlfriend, changes his phone number, but nothing works.’

I look away, back at my black-socked feet. I slide them under the bar.

‘So this man gets on a plane to another new country, she says. ‘He lands, and he feels just the same as always. It’s different, but any arrivals lounge is much like any other. This place doesn’t surprise him either. So, he walks through arrivals and he sees people holding up boards with names. Then he chooses a name at random, and goes up to the person holding the board — and he says, that’s me.’

She looks up at me, and pushes up a long dark eyelash with the back of a finger.

‘So then what happens to him?’

‘That’s just it,’ she says. ‘That’s exactly the point at which things start to get surprising.’

‘So you think that’s what I should do?’

She makes a do what you want gesture with one hand and her face.

‘Or you could waste two weeks of your life in a car and motels, meeting a colourful cast of loveable eccentrics who teach you what you already know, leading you to an ending you can already predict.’

I walk through the double doors. There’s a cluster of people standing there, some are straining to look through the doors, some have already seen the person they’re waiting for, some have already met them, and some are holding up signs with names on. There’s ABR SERVICES and UBEROPTICS; Hudson Franks and Carlie Ramos. I will leave here, go to my hotel, find somewhere to have a drink, maybe somewhere different to eat, go back to my hotel, have breakfast — there are no real surprises left. Nothing tectonic is possible anymore. BRUCE WU and Erika Richter, CHRISTIAN MARTINEZ, Candice Cypret, RHD SUPPLIES... There’s a tall man with a black suit and slicked back grey-black hair. I’m standing right by him.

‘What?’ he says.

He’s holding a sign with a name.

‘That’s me,’ I say.

‘You’re TANNISHTHA KAUSHIK?’

I go: ‘Yeah’.

‘You got luggage?’

I make a gesture from my chest down. ‘All I’ve got.’

So he goes: ‘Let’s go.’

And I go: ‘Yeah’.

I have no idea where I’m going, who I am, what I’m here for, or what I’m about to do.