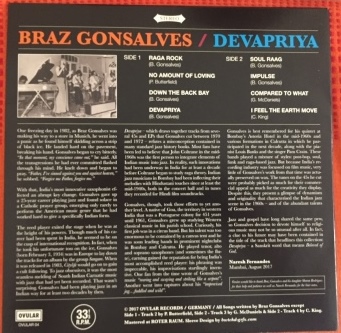

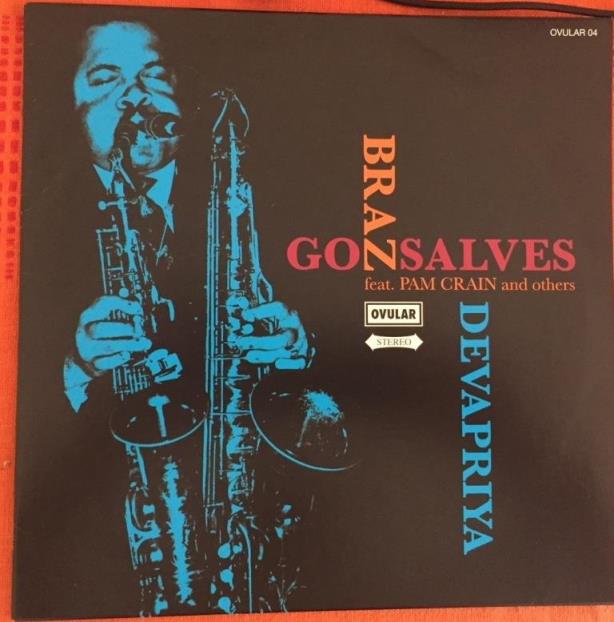

A few months ago, I received a request from the excellent Florian Pittner, who runs Hindustani Vinyl, the online record store that with the best collection of classic Indian and Pakistani pop you could ever hope to find. He and his friends at Ovular Records wanted to compile a bunch of Braz Gonsalves 45s as a 10-inch record, he said. Would I write the liner notes? How could I resist the offer?

The disc arrived in the mail this morning. Here, for what it’s worth, is the text on the back.

One freezing day in 1982, as Braz Gonsalves was making his way to a store in Munich, he went into a panic as he found himself skidding across a strip of black ice. He landed hard on the pavement, breaking his hand. Gonsalves began to cry bitterly. “In that moment, my conscience came out,” he said. All the transgressions he had ever committed flashed through his mind. He knelt down and began to pray. “Father, I’ve sinned against you and against heaven,” he sobbed. “Forgive me Father, forgive me.”

With that, India’s most innovative saxophonist effected an abrupt key change. Gonsalves gave up a 25-year career playing jazz and found solace in a Catholic prayer group, emerging only rarely to perform the American music genre that he had worked hard to give a specifically Indian form.

The reed player exited the stage when he was at the height of his powers. Though much of his career had been spent in India, he seemed to be on the cusp of international recognition. In fact, when he took his unfortunate toss on the ice, Gonsalves (b February 3, 1934) was in Europe to lay down the tracks for an album by the group Sangam. When it was released in 1983, Citylife would go on to gain a cult following. To jazz obsessives, it was the most seamless melding of South Indian Carnatic music with jazz that had yet been recorded. That wasn’t surprising. Gonsalves had been playing jazz in an Indian way for at least two decades by then.

Devapriya – which draws together tracks from several 45s and EPs that Gonsalves cut between 1970 and 1972 – refutes a misconception contained in many standard jazz history books. Most fans have been led to believe that John Coltrane in the mid-1960s was the first person to integrate elements of Indian music into jazz. In reality, such innovations had been underway in India for at least a decade before Coltrane began to study raga theory. Indian jazz musicians in Bombay had been inflecting their melodies with Hindustani touches since at least the mid-1940s, both in the concert hall and in tunes they recorded for Hindi film soundtracks.

Gonsalves, though, took those efforts to yet another level. A native of Goa, the territory in western India that was a Portuguese colony for 451 years until 1961, Gonsalves grew up studying Western classical music in his parish school. Curiously, his first job was in a circus band. But his talent was too enormous to be contained by a canvas tent and he was soon leading bands in prominent nightclubs in Bombay and Calcutta. He played tenor, alto and soprano saxophones (and sometimes the flute), earning gained the reputation for being India’s most accomplished reed player: his phrasing was impeccable, his improvisations startlingly inventive. One fan from the time wrote of Gonsalves’s music “rearing and swaying and striking like a serpent”. Another went into raptures about his “improvised jag…fuddled and wild”.

Gonsalves is best remembered for his quintet at Bombay’s Astoria Hotel in the mid-1960s and various formations in Calcutta in which he participated in the next decade, along with the pianist Louis Banks and the singer Pam Crain. These bands played a mixture of styles: post-bop, soul, funk and raga-based jazz. But because India’s recording industry was focussed on film music, very little of Gonsalves’s work from that time was actually preserved on wax. The tunes on the 45s he cut were probably picked as much for their commercial appeal as much for the creativity they display. Despite this, they present a glimpse of dynamism and originality that characterised the Indian jazz scene in the 1960s – and of the abundant talents of Gonsalves.

Jazz and gospel have long shared the same pew, so Gonsalves decision to devote himself to religious music may not be so unusual after all. In fact, a clue to his future may have been contained in the title of the track that headlines this collection: Devapriya – a Sanskrit word that means Beloved of God.