… position paper published by the Guerrilla Resistance in the mid-80’s … circulated, but not, as far as I know, published … concentrating on “questions of strategy organization, and tactics,” and making “particular arguments about armed clandestine organization and armed propaganda” …

Red Guerrilla Resistance

The Red Guerrilla Resistance is a communist politico/military organization comprised of  revolutionaries from the North American oppressor nation. Over the last few years we have initiated a program of armed propaganda and done a number of armed actions under the name of the Revolutionary Fighting Group and Armed Resistance Unit.

revolutionaries from the North American oppressor nation. Over the last few years we have initiated a program of armed propaganda and done a number of armed actions under the name of the Revolutionary Fighting Group and Armed Resistance Unit.

We are releasing this paper at this time for a number of reasons:

1) To contribute to the development of revolutionary theory. We feel that our entire movement is being held back by the refusal of communist elements to deal seriously with our task of developing theory. “Breakthrough” is the only theoretical organ sustained by our part of the Left, and, it makes an important contribution. It is not adequate, though, both because of its infrequency and because there are real strengths and weaknesses that come with being an organizationally defined journal.

We are not yet in a position to publish a regular journal ourselves, so we must ask comrades to reprint and circulate this and future statements.

We do want to contribute to the struggle in our movement by putting forward some of our ideas in a formal and written fashion. We think it is a grave problem that major political and strategic issues are being argued out in our movement in an informal and thereby, unaccountable fashion.

Without written materials, it is difficult to rigorously analyze positions. Criticism must therefore remain largely empirical: this worked or this didn’t. That may be adequate for tactical questions, but will leave us unable to take on larger questions of line or strategy.

The decisions that we arrive at matter not only to our own movement but to Third World comrades as well. Open struggle allows comrades from other movements to have input and creates a basis for principled relationships. We liquidate any reality to strategic Third World leadership if we don’t make those strategic questions accessible to them.

The circulation of written positions enables comrades in prison to participate. They are some of the best cadre produced by our movement and their contribution should be maximized. While they as individuals have their mass work defined by their material conditions, their degree of isolation is largely determined by how actively our movement engages with them. The more our movement produces journals, papers, and hopefully at some point, a newspaper, the more these comrades can contribute and continue to grow.

We realize that some of these developments await the future growth of our movement. At the same time, we think it is partially due to an anti-theory position that needs to be overturned. We also think that theoretical struggle and development will help us to achieve that growth.

We are also acutely aware of security issues involved in writing: this paper is both more concrete than we would like vis-a-vis the state and less concrete than we would like vis a-vis our comrades. We think that adequate compromises can be reached.

2) We have a specific focus for this paper. We are going to concentrate on questions of strategy organization, and tactics. Issues of political line will be addressed more in this context than as separate ideological arguments.

Within that, we will make some particular arguments about armed clandestine organization and armed propaganda. This emphasis does not stem from a position that we are the only communists responsible for this or that it is the only area we can discuss. Rather, we emphasize it because it is a central issue and the focus of considerable debate , and we do believe that we have particular experience and perspective to contribute. Part of that perspective is that we believe that the existence of the current armed clandestine movement has transformed the question facing our movement from one of how to support armed struggle to one of how to build it.

As will become apparent in the body of this paper, we think that how we pose the questions for debate and the very concepts and terms that we utilize in the struggle will largely determine the outcome. We have disagreements with how this is proceeding as well as with some of the positions and practices that are emerging. Since there is no organization that can speak for us on these issues, we wish to make our own voice heard.

3) To heighten the level of mutual accountability between the public movement and the clandestine movement.

Our organization has a dual nature.

As a communists organization, we have our own line, strategy, and program just as public communist formations do. We fight for those things, as evidenced by this paper.

At the same time, part of our program is armed propaganda. We are very aware of the fact that this practice helps determine some of the conditions under which a wide range of anti-imperialist forces, Third world as well as white, do their work. We have tried very seriously to avoid organizational chauvinism or political sectarianism in our actions and communiques. We try as much as possible to speak for our revolutionary anti-imperialist tendency and not just an organizational line. We believe that the United Freedom Front tries to have a similar perspective on a mass line.

Our own evaluation at this point is that we have largely been successful at this and that armed propaganda plays a positive role in our movement. We don’t believe that it is just up to us to determine that, however, and we invite evaluation from comradely organizations as part of promoting mutual accountability.

We do believe that accountability is a two-way street and that public anti-imperialist organizations that support the armed clandestine movement should do so in a consistent and non-sectarian fashion. We will put forward at the end of this paper our proposal for how this should be done.

4) To build support for captured combatants.

A significant number of cadre from both oppressor and oppressed nations have been captured over the past year and a half and charged by the FBI with building armed clandestine organizations. Particular charges may not be true in particular cases, but these comrades have clearly identified themselves as either political prisoners or POWs and as supporters of armed struggle.

A significant number of cadre from both oppressor and oppressed nations have been captured over the past year and a half and charged by the FBI with building armed clandestine organizations. Particular charges may not be true in particular cases, but these comrades have clearly identified themselves as either political prisoners or POWs and as supporters of armed struggle.

We don’t think that the support given these comrades by our movement has been adequate. It seems to us that there has been a self- conscious distancing going on by comrades in the public movement. We assume that this reflects a political vacillation on the role of armed clandestine organizations in this period. When applied to the Third World comrades, this become racist. We hope that by taking on this underlying political struggle that we will make a contribution to build support for those captured comrades currently facing charges and for all imprisoned political prisoners and POWs.

This paper is both lengthy and touches on many issues. It encompasses questions of ideology, line strategy and tactics while trying to stay rooted in some contact with the actual practice of our movement. We primarily want to put forward what we do think but also will raise things that we don’t agree with. It is a little eclectic and would benefit from being more tightly structured; those weaknesses are accurate reflections of the development of our thinking. We thought it more important to have the paper out for broader discussion and struggle than to try to perfect it internally.

We could start at anyone of a number of places. We’ve chosen to start with a brief section that directly deals with the issue of support for captured comrades. We start here because we think that there is an urgency to building support for these comrades and because we think that the conflicts over how to support them reflect in a concrete fashion come of the more general line struggles that are going on.

SOME GENERAL LESSONS FROM RECENT SETBACKS

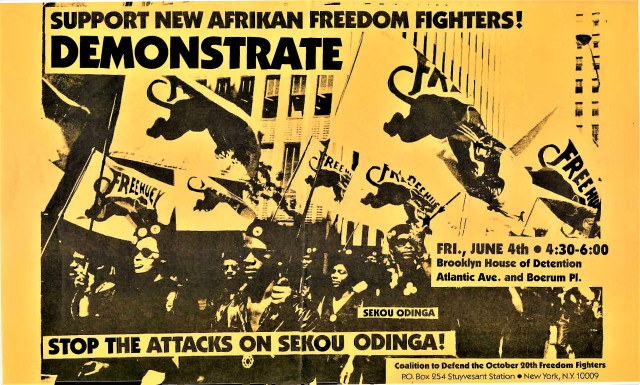

Over the past 18 months, 4 comrades from the Puerto Rican Independence Movement, 8 comrades from the New Afrikan Independence Movement, and 7 North Americans have been arrested and charged by the government with building armed clandestine  organizations. Some of these comrades have openly stated that they are combatants; others say that they are not but that they do support the building of such organizations.

organizations. Some of these comrades have openly stated that they are combatants; others say that they are not but that they do support the building of such organizations.

While any or all of the specific government allegations may be false, there is no question that there are important lessons to be learned from these captures. Some of them are specific, and each grouping of comrades will need to decide how those lessons are to be analyzed and fought for within their own nations and within the overall revolutionary struggle in this country. Revolutionaries from each nation will need to analyze how these lessons apply to the further development of their struggle.

We want to address the North American anti-imperialist movement. We are concerned that our movement is not learning the correct lessons, and so will be condemned to repeat certain errors. That would be tragic and unnecessary. It would be still worse if we are not learning the lessons because we don’t think we need armed clandestine organization.

1) We know that some comrades in our movement have examined some of the recent arrests and drawn out the lesson that the “principle of separation” was violated. Captured comrades are criticized for jeopardizing the public movement, and this is used to justify the further withholding of support. Separation, which is actually a tactic, is elevated progressively to a strategy and finally a revolutionary principle. The logical outcome of this criticism is a construct that creates a gulf between the “public” movement and· the clandestine movement, between “public communists” and clandestine communists.

This is directly contrary to our vision of a revolutionary movement that is increasingly united by common principles, strategy, and ultimately by a unified revolutionary organization.

One conception of politico/military organization is that of a single organization that helps to build and lead both the political and military fronts and increasingly unites the two. Within a politico/military organization there can be a tactical separation between those who are defined as combatants and those who are primarily mass workers. Either category of member may be underground or aboveground, but the entire organization is clandestine . The exposure of part of the membership of such an organization might well include people who are known primarily as mass leaders. as mass leaders. While the errors that led to such an exposure have to be analyzed, the fact that combatants and non-combatants are in the same revolutionary organization is not itself an error in our

estimation. We believe that this model of politico-military organization is one that has been implemented in many different movements. We do believe that there is an important lesson to be learned: given the historical development of our movement, the building of effective clandestine organizations requires that some number of cadre go underground and build an underground clandestine core. We are too small and too exposed to the state to build from “the top down”. This is a strategic issue for our entire movement, for we need to produce the kind of cadre who are willing and capable of building an underground. Rather than distancing from the clandestine movement, public comrades should be concerned with the health, survival, and future path of the armed clandestine movement. Most specifically, we think that public comrades should be concerned with the question of people to replace those who have been captured.

2) Many errors have been made in the course of building clandestinely and, those of us who make them need to take responsibility for them. It is important to understand, though, that functioning clandestinely is difficult, and that it’s particularly difficult in

2) Many errors have been made in the course of building clandestinely and, those of us who make them need to take responsibility for them. It is important to understand, though, that functioning clandestinely is difficult, and that it’s particularly difficult in

the early stages when you’re first figuring out how to do it. The lesson to be learned from the arrests is not that building armed clandestine organizations is impossible, but neither is it that comrades were just careless.

Instead, we need to learn specific lessons from what happened and draw whatever general conclusions we can. It’s important to recognize that correct clandestine procedure involves a constant struggle against opportunism; this entails a fight against all forms of subjectivity and a commitment to objectivity and science. We sincerely believe that the quality of careless error that results in capture or other disaster at the armed clandestine level is made by comrades in the public movement all the time. The ramifications are so much less, though, that the error is barely noticed. We know this because some of us have made those errors in both sectors of our movement.

Clearly, the issue isn’t to justify errors. Rather, we need to understand that life in the public movement has historically not trained people well for clandestinity. More importantly, we believe that that can and should be changed. Combativity, competency, and discipline will benefit all aspects of our movement and will distinguish it as a movement worthy of being joined and supported. We believe that one of the real strengths that will come from our movement having an active armed clandestine movement is that concrete lessons that come from clandestine work in general and military work in specific can be utilized in all areas.

3) All of the captured comrades are people who have made an exemplary and leading commitment to fight imperialism. All should not only be supported but respected and emulated. We have encountered comrades who seem much more conscious of the errors that were made than of the heroism and determination that motivates the captured comrades. Without validating the state’s allegations, it is striking that one consistent theme is that these captured comrades were working on freeing political prisoners and POWs. Our movement has always seen this as a strategic task and has celebrated the liberation of William Morales and Assata Shakur. Those who struggle to give some reality to the slogans of our movement should be recognized and respected for their efforts and not just criticized for their errors. It is definitely true that waging armed struggle does not make an individual or an organization correct on any single political issue, but if we do recognize that it is the most difficult form of struggle and requires deep ideological commitment, then we should all listen to and engage with these comrades on a very serious level.

3) All of the captured comrades are people who have made an exemplary and leading commitment to fight imperialism. All should not only be supported but respected and emulated. We have encountered comrades who seem much more conscious of the errors that were made than of the heroism and determination that motivates the captured comrades. Without validating the state’s allegations, it is striking that one consistent theme is that these captured comrades were working on freeing political prisoners and POWs. Our movement has always seen this as a strategic task and has celebrated the liberation of William Morales and Assata Shakur. Those who struggle to give some reality to the slogans of our movement should be recognized and respected for their efforts and not just criticized for their errors. It is definitely true that waging armed struggle does not make an individual or an organization correct on any single political issue, but if we do recognize that it is the most difficult form of struggle and requires deep ideological commitment, then we should all listen to and engage with these comrades on a very serious level.

4) We have heard an emerging position that a lesson to be learned is that armed clandestine organizations cannot survive until there is more mass support. It is definitely true that the support of the masses is a qualitative factor in the development of all aspects of the struggle, including the armed clandestine movement. Even a the level of infra-structure, it is far better to have active support from a wide range of people than to rely on public services and institutions.

However, we firmly believe from our own experiences and analysis of other organizations, that armed clandestine organizations can exist now. They will be small, as our movement and public organizations are small. As the movement grows, so will the A.C.M. It’s existence, in fact, should help make that growth possible. The lack of support among the masses of the oppressor nation should not be used to justify a lack of support from conscious revolutionary elements.

5) Expropriations are an integral part of building an active armed clandestine movement. They are neither great revolutionary actions nor simple criminal activity — they are a revolutionary necessity. If a movement is not at the stage where it commands the financial support of the masses nor is in a position to demand revolutionary taxes from the wealthy, it needs to take the money necessary to sustain cadre and build infrastructure. We are sure that great care is taken by every revolutionary organization to avoid injury to civilians, to minimize confrontation with the police forces, and to never take a penny from the masses.

SOME STRATEGIC PREMISES AND POLITICAL CHANGES

The decision to build an armed clandestine organization was neither spontaneous nor primarily determined by legal considerations. In some ways, though, it was· done much more out of desire than be scientific design.

We want to schematically put forward some of the thinking that underlay our initial formation and the subsequent changes in line, strategy and organizational thinking that we have undergone. We hope that it will not only clarify specific issues about our organization but will also contribute to the larger strategic debate going on in our movement.

Some of the general strategic premises that guided our initial decision were:

1) Our movement needed a multi-level capacity to fight alongside national liberation  struggles – particularly those of the oppressed nation of the U.S. federalist state. Revolutionary forces in the New Afrikan, Puerto Rican, and Mexican movement had long made clear that armed struggle is an integral part of the development of their movements and not just a spontaneous mass phenomenon that appears just before a final insurrection, It’s also been clear that serious white allies could play an important role. Revolutionary struggle takes place on all levels, but we knew that we had a lot to learn if we were going to be able to build a military capacity.

struggles – particularly those of the oppressed nation of the U.S. federalist state. Revolutionary forces in the New Afrikan, Puerto Rican, and Mexican movement had long made clear that armed struggle is an integral part of the development of their movements and not just a spontaneous mass phenomenon that appears just before a final insurrection, It’s also been clear that serious white allies could play an important role. Revolutionary struggle takes place on all levels, but we knew that we had a lot to learn if we were going to be able to build a military capacity.

2) We believed that our movement needed an offensive capacity. Even at the earliest stages, the armed clandestine movement gives a capacity to attack. Our movement needs this even though we’re strategically at very early and defensive stage in the struggle against U.S. imperialism. We need to be able to respond to the offensives of Third World struggles with an offensive of our own. The rules of attack, like all rules of war, need to be learned, and the armed clandestine movement is the best place to learn them. Then they need to be generalized and applied to all forms of struggle.

3) We believed our movement needed a defensive capacity. After October 20th, 1981, May 19th and other anti-imperialist comrades in the New York area began to get a sense of the kind of repression that has primarily been directed at revolutionary Third World comrades for a long time. We also knew that it was just the beginning. It was absolutely correct and important to fight at the public level in Goshen, against the federal RICO case and against the grand jury, but we also needed the capacity to resist on our own terms as a revolutionary movement. We also felt that with the further development of the overall struggle, the armed clandestine movement could give a capacity to retaliate — an important part of. the fight against repression .

We still think that these premises are valid, and perhaps would be adequate if we were building the “military wing” of a revolutionary movement with an established and correct political line and strategy. We increasingly felt that wasn’t the case.

We began to realize that “building the armed clandestine movement” was not an adequate definition of our task. The armed clandestine movement can be comprised of many different types of organization: underground collectives that do only military work, clandestine collectives of aboveground people who do armed actions, political organizations of varying ideologies who have armed actions as part of their program. They are all part of a “movement” just as the public movement is made up of numerous types of organizations.

We began to grapple more with the concept of a communist clandestine politico-military organization. We particularly treated to analyze and apply the concepts that Don Juan Antonio Corretjer and other comrades from the revolutionary Puerto Rican  Independence Movement have fought for over the years. We increasingly felt that as communists, we had as much responsibility as other communist formations in our movement for an overall line and strategy for the anti-imperialist struggle in the oppressor nation. Armed struggle needed to be waged in the context of a clear and correct revolutionary anti-imperialist line and as part of a self-conscious strategy to build a revolutionary movement.

Independence Movement have fought for over the years. We increasingly felt that as communists, we had as much responsibility as other communist formations in our movement for an overall line and strategy for the anti-imperialist struggle in the oppressor nation. Armed struggle needed to be waged in the context of a clear and correct revolutionary anti-imperialist line and as part of a self-conscious strategy to build a revolutionary movement.

As a first step, we looked critically at the history of our sector of the left in an effort to define our strengths and weaknesses. We tried to analyze not only the efforts to build armed clandestine organization but our work in the public movement as well. We were limited by how little good written material is available and primarily had to draw on individual experiences. These are clearly limited but did extend back to the early 1960s and did encompass varying organizational experiences in the anti-imperialist movement.

We have had some struggle with comrades who characterize the dominant error of our tendency as militarism. We don’t really agree with that so we would like to put forward some of our analysis of our tendency’s history and then draw out some of the errors that we think need to be addressed.

Our revolutionary anti-imperialist tendency developed in response to the rise of national liberation struggles – in particular, that of the Vietnamese and of the Black liberation struggle. Education and mobilization went on among broad sectors of the white oppressor nation; there were numerous mass organizations within which self-conscious revolutionaries could work and organize. A number of communist and cadre-type organizations developed out of the New Left including what eventually became the Weather Underground Organization. It is interesting to note that these groupings formed a the peak of or actually shortly after the peak of mass struggle in this country.

The societal contradictions subsided with the victory of the Vietnamese and the temporary but serious setback for the Black Liberation Struggle. White revolutionary anti-imperialists found themselves with no mass base for their politics and no long-term strategies. It was an objectively difficult period.

The response of most of the New Left communist formations was to join the Old Left in the morass of reformist working class organizing. The WUO, on the other hand, gave a “hippie” and petit-bourgeois bent to their plunge into opportunism. Rather than try to build a base for anti-imperialist politics, they tried to construct a mass movement by building a coalition between the “anti-imperialist” and the reformist “base-builders.” They correctly recognized that there were numerous secondary contradictions in this society that affect white people and bring them into some conflict with the system; what they refused to do was apply the primary contradictions of national liberation and  imperialism to each of the secondary contradictions and struggle to win people to anti-imperialism as a strategy for revolutionary change. Instead, national liberation struggles became one more “interest group,” all contradictions were equal, a nice shopping list of demands was drawn up, and “unpopular” demands were minimized or side-stepped. Given the nature of the white oppressor nation, some of the more “unpopular” demands included self-determination for the New Afrikan / Afro-American nation, Independence for Puerto Rico, issues of seniority and affirmative action, and any struggle against Zionism. As is often the case, armed struggle went out the window along with anti-imperialism.

imperialism to each of the secondary contradictions and struggle to win people to anti-imperialism as a strategy for revolutionary change. Instead, national liberation struggles became one more “interest group,” all contradictions were equal, a nice shopping list of demands was drawn up, and “unpopular” demands were minimized or side-stepped. Given the nature of the white oppressor nation, some of the more “unpopular” demands included self-determination for the New Afrikan / Afro-American nation, Independence for Puerto Rico, issues of seniority and affirmative action, and any struggle against Zionism. As is often the case, armed struggle went out the window along with anti-imperialism.

Criticisms were made by New Afrikan comrades and there was a rectification of our tendency’s line. It proceeded through a number of stages including one in which imperialism had three pillars (national oppression, class exploitation, women’s oppression) rather than primary and secondary contradictions. Continued struggle by New Afrikan comrades, as well as a clear two line struggle over how to analyse and relate to the bourgeois women’s movement (the Houston Women’s Conference) in specific, finally led to the emergence of a clear position on the primacy of national liberation. On the East Coast, at least, it took the specific form of a line on the centrality of the Black Liberation struggle.

The WUO itself split and then dissolved. During the course of the struggle, it was exposed that members of the WUO had unprincipledly and undemocratically manipulated certain public formations. Unfortunately, a position arose in reaction to this practice that communist clandestine organizations are inherently unprincipled or that public leaders should not be members of clandestine organizations.

With the split in PFOC, we can speak directly about events on the East Coast. We were undialectical. We increasingly felt given the reality of white supremacy and opportunism, that we could only deal with the primary contradiction. We eliminated any of the secondary contradictions that defined real society.

1. National liberation became an abstraction, particularly the struggle of oppressed nations internal to the U.S. borders. This was racist and we ended up unable to support the human rights struggles of Third World people on a principled basis.

Having reduced everything to an “idea” of self-determination, we could not see that the contradiction expressed itself through the daily struggles for human rights that Third World people wage. Killer cops, white supremacist violence, unemployment, health care, housing – the struggle against the concretes of national oppression. They are also the areas where white revolutionaries could most directly struggle with white people about white supremacy since certain sectors of the white oppressor nation also experience some of these contradictions.

Having reduced everything to an “idea” of self-determination, we could not see that the contradiction expressed itself through the daily struggles for human rights that Third World people wage. Killer cops, white supremacist violence, unemployment, health care, housing – the struggle against the concretes of national oppression. They are also the areas where white revolutionaries could most directly struggle with white people about white supremacy since certain sectors of the white oppressor nation also experience some of these contradictions.

While Third World comrades struggled with us to understand the intimate connection between human rights struggles and revolutionary organizing, we often ended up pitting our support for revolutionary organization and revolutionary line against the concrete struggle struggles of Third World people. It was racist and interventionist.

IF we were going to characterize this error, we would say it was idealism (metaphysics). We were dogmatic, more concerned with the purity of an abstract line than with the implementation of a strategy to move real people into the struggle against imperialism.

We want to give an example of another form that idealism took in our movement. We were so defined by the idea that the struggles in the white settler colonies were the only strategic revolutionary struggle in the world that we could not deal with the struggle in Central America. We could understand the significance of the victory in Zimbabwe, but not that of the Sandinistas in Nicaragua. It is “a priorism” – we had decided in our minds that only the white settler colonies were strategic, therefore, Central America could not be.

2. We made the white oppressor nation homogenous and without contradiction. We were the exceptional white people. Having no internal contradictions, the white oppressor nation could only be acted upon by outside forces – the national liberation struggles. Our tendency, then, was to place ourselves inside the national liberation struggles and outside the white oppressor nation. We literally positioned ourselves on the periphery of the society and yelled at people from street corners.

We were sectarian. We removed ourselves from the complexities of the actual conditions of struggle in the oppressor nation and set up our own organizations. Often these organizations existed more to publicize a series of positions than to wage actual struggle against some aspects of imperialism. Communist organization simply had a more complete line and its members were full time activists. It didn’t, in our mind, have responsibility for a revolutionary strategy but was rather the coordinating centre for the different areas of mass work.

Why did we stay rooted in metaphysics and idealism? Some the major reasons that we could analyze were:

1. We were a petit-bourgeois movement in an imperialist centre with almost no history of significant Marxist-Leninist organizing. It is a struggle to become dialectical materialists, since it is not simply “common sense.” Our anti-ideological bias made sure it was never a priority.

2. Given the lull in revolutionary struggle in the world during the mid to late 70s and the ongoing low level of mass struggle inside this country, it was hard to figure out how to implement a real strategy based in revolutionary politics. Isolation was the easiest, but clearly not the best, way to deal with the realities of opportunism, white supremacy and reformism in even the most progressive sectors of the white oppressor nation.

3. Not dealing with secondary contradictions could be used as a rationale for not proletarianizing ourselves. To even seriously explore some of the secondary contradictions in the oppressor nation would have meant some of us taking more proletarian jobs or integrating ourselves into a community. We had internalized a lot of the negative aspects of “youth culture” and it became very convenient for many of us to get “hustles” rather than serious jobs and justify it by citing the need to do “political work.” The fact that a number of adults would live together often enabled us to live in gentrified neighborhoods rather than working class neighbourhoods and there was little basis for community work in those areas. We don’t mean to say that the only secondary contradiction is the class contradiction, but it is the secondary contradiction that has the most potential for being antagonistic in the long run. If our opportunism around this continues, it guarantees that we will not be in a position to do a serious class analysis to guide our revolutionary organizing.

The break with sectarianism involves far more than learning to work in coalition with forces that we don’t have total unity with. More fundamentally, it means a willingness on our parts to transform ourselves and work with some sectors of the white “masses” and build a base for our politics.

4. Idealism meant that we could talk about a strategy of waging armed struggle but never had to do it. We didn’t build armed clandestine organization but rather public organization. Most of the confrontation we had as a movement resulted from interaction with the pigs or the right-wing when they tried to interfere with our street tables or public events. We mostly avoided any confrontation with the Klan, for example, whether it was in Connecticut or in Washington, D.C. In Washington, for example, we let Third World people fight the Klan in the streets while we retired to a nearby church.

Why do we call these errors sectarianism and dogmatism rather than militarism and focoism?

Not because there weren’t some militaristic aspects to our line but because our articulated line did not govern our strategy. We had, at various times, a militarist understanding of people’s war, whether in the early stages in Puerto Rico or in the culminating period in Zimbabwe. Through political struggle and criticism from Third World comrades even that began to change though, and we increasingly recognized the role of politicization of the masses in protracted people’s war.

Not because there weren’t some militaristic aspects to our line but because our articulated line did not govern our strategy. We had, at various times, a militarist understanding of people’s war, whether in the early stages in Puerto Rico or in the culminating period in Zimbabwe. Through political struggle and criticism from Third World comrades even that began to change though, and we increasingly recognized the role of politicization of the masses in protracted people’s war.

Yes, we often dealt wit the strategic concept of war in America as if it were a concrete description of our current realities, and we would distort the realities to march our ideas. And we sometimes made the militarist error of separating military tasks from political tasks and assumed that only those who picked up the gun would lead.

But militarism is a real strategy that involves the building of real armies, just as focoism was a real strategy in Latin America where thousands of committed revolutionaries went to the countryside and built the guerrilla focos. They died implementing a strategy, not simply propagandizing and idea.

Perhaps the WUO was implementing a militarist strategy and trying to adopt focoism to this country for a brief moment when almost the entire organization went underground and withdrew from mass work. Once the townhouse happened though, that strategy was gone and it isn’t real to label that organization “militarist” when they criticized the BLA for fighting the police in the Black community. Opportunist would be more correct.

After the Hard Times Conference, was our tendency militarist? Although the LA-5 were busted for attempting to do an armed action, the reality was that there was not one functioning armed clandestine organization developed by our tendency until 1982. The reality is that we largely dismantled clandestine structures and built public revolutionary organizations.

In reality, our strategy was two-fold: to educate some white people from a distance by articulating at line, and to take advantage of our colour and class to gather material aid for various national liberation struggles. At points, and at our best, we did mobilize ourselves and a small periphery to fight organized white supremacist forces on a mass level.

On the East Coast, a small number of individual “leaders” did aid clandestine Third World forces, but is was so peripheral to the main thrust of our strategy that it was somewhat of a part-time task for them. This doesn’t mean that that relationship wasn’t valuable, but it was so marginal to our strategy that no coherent plan was ever formulated yet alone implemented, to make it a consistent or growing part of the practice of our tendency.

World forces, but is was so peripheral to the main thrust of our strategy that it was somewhat of a part-time task for them. This doesn’t mean that that relationship wasn’t valuable, but it was so marginal to our strategy that no coherent plan was ever formulated yet alone implemented, to make it a consistent or growing part of the practice of our tendency.

It would be an error to take our verbal positions as the primary object of critical analysis rather than our objective practice. We will end up with criticisms that are as idealist – even if more “correct” – than our earlier formulations. The tendency in correcting for militarism is to withdraw support for armed struggle – a conclusion that will liquidate one of the real strengths of our movement. It is a phenomenon that is occurring – not necessarily at the level of “line” at the moment, but in a number of very concrete ways. We need to correct our errors of sectarianism and dogmatism or else we will make no significant contribution to the revolutionary process here. We need to not only theoretically recognize the role of the masses in making revolution, but we need a program to proletarianize ourselves and be in a position to organize. We cannot continue to avoid struggling against the realities of white supremacy and male supremacy in this society by creating a self-contained mini-environment called “the movement.” But we will be opening up the doors of opportunism very wide if we approach these necessary changes with a theoretical construct that labels as ” militarist” a tendency that has produced barely a handful of guerrillas and has almost never taken up arms in anger.

A line and strategy cannot be reduced to the individual, but the cadres are a product of the line. Looking at our own profound weaknesses as guerrillas, we have great difficulty in seeing our movement’s problem as militarism. We collectively encompass years of “military” experience of our movement, both in the building of the WUO and in the direct solidarity with clandestine Third World organizations. We are not just talking

A line and strategy cannot be reduced to the individual, but the cadres are a product of the line. Looking at our own profound weaknesses as guerrillas, we have great difficulty in seeing our movement’s problem as militarism. We collectively encompass years of “military” experience of our movement, both in the building of the WUO and in the direct solidarity with clandestine Third World organizations. We are not just talking  about our collective unfamiliarity with weapons or some individuals active aversion to them; we are not just referring to the struggle its been to understand how to analyze a military situation and develop a plan for taking control. More fundamentally, we are talking about our lack of combativity. Combativity is the putting into practice of our commitment and will to win; it is an issue of ideology and not just training or innate aggressiveness. For white guerrillas to be enemies of the state requires a constant struggle for combativity, fighting against the bonds of white supremacy and privilege that tie us to the state and sometimes make us feel that we have more to lose than to win by fighting. Combativity involves being willing to take the offensive and not be defined by the terms set by the state. Heightening the struggle at any given point may be riskier, but in that risk, scientifically assessed and taken, like the potential for victory. We believe that these are critical lessons for our entire movement and not just for military combatants. Combativity in no way guarantees the correctness of a strategy, but a lack of combativity guarantees that no strategy will succeed. Our own struggles to become

about our collective unfamiliarity with weapons or some individuals active aversion to them; we are not just referring to the struggle its been to understand how to analyze a military situation and develop a plan for taking control. More fundamentally, we are talking about our lack of combativity. Combativity is the putting into practice of our commitment and will to win; it is an issue of ideology and not just training or innate aggressiveness. For white guerrillas to be enemies of the state requires a constant struggle for combativity, fighting against the bonds of white supremacy and privilege that tie us to the state and sometimes make us feel that we have more to lose than to win by fighting. Combativity involves being willing to take the offensive and not be defined by the terms set by the state. Heightening the struggle at any given point may be riskier, but in that risk, scientifically assessed and taken, like the potential for victory. We believe that these are critical lessons for our entire movement and not just for military combatants. Combativity in no way guarantees the correctness of a strategy, but a lack of combativity guarantees that no strategy will succeed. Our own struggles to become  guerrillas have deepened our respect for that will to win that has characterized some of our comrades of the Black Liberation Army, William Morales, and some of those comrades recently captured in Cleveland.

guerrillas have deepened our respect for that will to win that has characterized some of our comrades of the Black Liberation Army, William Morales, and some of those comrades recently captured in Cleveland.

Based in this struggle and many others that we won’t go into here, we made a number of changes in the political line and strategy of our organization. Some of the major ones are:

1. We reaffirmed the strategic conception of revolutionary anti-imperialism led by national liberation struggles. Within that, we reaffirmed the strategic leadership of those oppressed nations internal to the federalist state and of Puerto Rico for the revolutionary struggle here. We thought we had been wrong, though, in mechanically translating this into a position that white people should only function internal to various national liberation struggles.

We want to be clear that we think that this can be a leading form of proletarian internationalism for individual, and that solidarity brigades have a long and illustrious history in the world revolutionary movement.

Where we saw a problem was in the history of communists from the oppressor nation maintaining their own organizational form, political line and program, and internal discipline while functioning internal to Third World organizations. We believe that some of us had attempted to use this position for “leverage” in promoting our own line and even our own small organizations with our Third World comrades. Correspondingly, within our own movement, we tried to use our relationships to Third World comrades to gain influence or prestige in an unprincipled fashion. This interventionism reinforced personal racism in our movement rather than combatting it and led to a practice of blaming Third World comrades and movements for our own weaknesses.

even our own small organizations with our Third World comrades. Correspondingly, within our own movement, we tried to use our relationships to Third World comrades to gain influence or prestige in an unprincipled fashion. This interventionism reinforced personal racism in our movement rather than combatting it and led to a practice of blaming Third World comrades and movements for our own weaknesses.

The greatest strength of our movement for years has been our sincere commitment to self-determination of oppressed nations, and particularly those most directly oppressed by “our” oppressor nation. We went underground largely to build our movement’s capacity to fight on the military level for the liberation of oppressed nations. We did not want to compromise that through continued attempts at intervention – racist and unprincipled in any form, and potentially disastrous at the armed level where leadership and discipline in any specific situation needs to be absolutely clear.

We have tried to build a communist organization of revolutionaries from the oppressor nation that is steeped in proletarian internationalism, with an anti-imperialist strategy and program, and which has a specific commitment to direct solidarity work and appropriate material aid. Relationships with Third World movements are guided by a firm commitment to uphold the right of self-determination; non-intervention in internal affairs; the upholding of all agreements and commitments; mutual respect, integrity, and honesty; ongoing internal struggle over any manifestations of racism and national chauvinism.

We have tried to build a communist organization of revolutionaries from the oppressor nation that is steeped in proletarian internationalism, with an anti-imperialist strategy and program, and which has a specific commitment to direct solidarity work and appropriate material aid. Relationships with Third World movements are guided by a firm commitment to uphold the right of self-determination; non-intervention in internal affairs; the upholding of all agreements and commitments; mutual respect, integrity, and honesty; ongoing internal struggle over any manifestations of racism and national chauvinism.

2) We recognized that we had an incomplete and incorrect understanding of the world imperialist system. Our analytical framework had actually been the system of white supremacy. Both systems obviously exist and are tightly interlinked, but imperialism has to be the foundation on which our analysis and strategy are based. We were brought up against this problem when we found that an analysis based in white settler colonialism could not account for the obvious strategic importance of the struggle in Central America. This seems obvious now but was not the position of much of our movement in 1982.

Our strategy in based in an analysis that this period is defined by the struggle of  oppressed nations outside the U.S. borders, and that Central America in particular is a weak link in the imperialist chain. As anti-imperialists, our priority – but not the whole of our program – is directed at adding our efforts inside the belly of the beast to those revolutionary forces in Central America and to the efforts of anti-imperialist peoples and nations around the world to break the imperialist chain at its weakest link. While we will not elaborate further, we also recognize that this world-wide front against imperialism has been significantly weakened by the impact of revisionism in both the Soviet Union and in China since the period of the Vietnam war.

oppressed nations outside the U.S. borders, and that Central America in particular is a weak link in the imperialist chain. As anti-imperialists, our priority – but not the whole of our program – is directed at adding our efforts inside the belly of the beast to those revolutionary forces in Central America and to the efforts of anti-imperialist peoples and nations around the world to break the imperialist chain at its weakest link. While we will not elaborate further, we also recognize that this world-wide front against imperialism has been significantly weakened by the impact of revisionism in both the Soviet Union and in China since the period of the Vietnam war.

3) We understand white settler colonialism as a primary form of imperialist domination. “Israel” and South Africa are major sub-imperialist powers that attempt to economically, politically and militarily dominate entire regions while colonizing the Palestinian and Azanian people. Support for the Palestinian and Azanian/South African struggles remains a strategic priority.

Internal to the U.S., white supremacy and zionism are key components of the state’s efforts to consolidate a base for fascism within the oppressor nation. The state has made it clear that it has no concern for Third World people’s lives, and white supremacist violence has more legitimacy than it has had in decades. While the progressive movement in the oppressor nation does not condone “extra-legal” racist violence, it has been notoriously reluctant to take a clear stand against killer cops and is openly a pro-zionist movement (or comfortably accommodates these elements).

4) If we are to break with sectarianism in the concrete, we need to develop a serious class analysis of the oppressor nation. Class analysis can bridge the gap between the sterile sectarianism of seeing the oppressor nation as homogenous and the classical opportunism of idealizing the white masses. Unfortunately, we’re not yet in a position to do that kind of analysis, and we haven’t seen it forthcoming from anyone else.

4) If we are to break with sectarianism in the concrete, we need to develop a serious class analysis of the oppressor nation. Class analysis can bridge the gap between the sterile sectarianism of seeing the oppressor nation as homogenous and the classical opportunism of idealizing the white masses. Unfortunately, we’re not yet in a position to do that kind of analysis, and we haven’t seen it forthcoming from anyone else.

We can put forward some thoughts that are currently guiding our analysis, but we readily admit that we need to do an enormous amount of social investigation and social practice.

We do think that there is an exploited proletariat among white people. As we’ll talk about later, we think it’s relatively small since we do not believe that the class structures themselves are transformed as the oppressor nation consolidated with the rise of imperialism. Capitalist exploitation, though, does create the material basis for revolutionary consciousness, although it in no way guarantees it. It is potentially an antagonistic contradiction, although we don’t believe the potential can be realized in this period. We don’t believe it will be realized until the primary contradiction of national liberation and imperialism is closer to resolution, and specifically until the national liberation struggles internal to the U.S. are more advanced.

about later, we think it’s relatively small since we do not believe that the class structures themselves are transformed as the oppressor nation consolidated with the rise of imperialism. Capitalist exploitation, though, does create the material basis for revolutionary consciousness, although it in no way guarantees it. It is potentially an antagonistic contradiction, although we don’t believe the potential can be realized in this period. We don’t believe it will be realized until the primary contradiction of national liberation and imperialism is closer to resolution, and specifically until the national liberation struggles internal to the U.S. are more advanced.

Why does it matter then? Because it becomes the strategic long-term goal of communists to organize and mobilize that class force to fight imperialism. Proletarianizing our movement becomes a strategic issue and not merely a moral one. While recognizing that the capitalist/worker contradiction is not currently a revolutionary one, it does mean that organizing some working class cadre should become a priority for our movement. And because the oppressed nations in this country are so overwhelmingly proletarian in composition, we now both from theory and from an analysis of the labour movement that the capital/labour contradictions will be a major front of the developing national liberation struggles.

We think that we, and our movement as a whole, has suffered from a lack of a consistent materialist approach to the oppressor nation. We hear numerous formulations about building a mass revolutionary movement in this period. We don’t think this is possible. Such a movement can only exist when some class force makes the overthrow of the state its strategic goal. In this period, revolutionaries are being organized as individuals and relatively small revolutionary organizations are the organizational embodiment of proletarian ideology in the oppressor nation. They are not a direct expression of the class struggle.

When we talk of a revolutionary movement as opposed to issue-oriented mass struggles,  we need to begin to formulate a program of demands. People overthrow governments for a reason, and the reason is not an abstraction like “socialism” or even less, “dictatorship of the proletariat”. Nations, classes, or some combination thereof seize political power and establish the dictatorship of the proletariat so that certain demands can be implemented that the imperialist state never will. We believe that communists in the oppressor nation must begin to formulate the basic elements of such a program as part of adopting a class perspective.

we need to begin to formulate a program of demands. People overthrow governments for a reason, and the reason is not an abstraction like “socialism” or even less, “dictatorship of the proletariat”. Nations, classes, or some combination thereof seize political power and establish the dictatorship of the proletariat so that certain demands can be implemented that the imperialist state never will. We believe that communists in the oppressor nation must begin to formulate the basic elements of such a program as part of adopting a class perspective.

We believe such a program should include:

1) The full liberation of oppressed nations. An end to imperialist war.

2) Full human rights for all. An end to all forms of national oppression.

3) An end to white supremacist violence and fascist terror.

4) The liberation of women and the destruction of the system of male supremacy.

5) Economic justice.

Revolutionaries fight for all these demands. In doing our actions and writing our communiques on the basis of a “mass line”, we had to struggle among ourselves to recognize that “peace” is a legitimate demand, “even” coming from white people. Not if it was peace based in imperialist domination, but peace if it involved and end to imperialist war and the liberation of oppressed nations. The masses around the world want peace and we couldn’t continue to delegitimize that demand when it came from people in the white oppressor nation. The issue becomes winning people over to anti-imperialist peace and not imperialist peace, and to recognize that peace cannot exist as long as oppression and exploitation do.

As a movement we’ve had real difficulty in correctly relating to the secondary contradictions in the oppressor nation. Our relationship to the struggle for women’s liberation is a concrete example.

We’ve long had a principle about the full liberation of women. At various times, though, this translated into a perspective that viewed women only as a sector of the oppressor nation that could be more easily organized to anti-imperialism because of women’s oppression. Any day-to-day struggles against the system of male supremacy were ignored and regarded as reformist. They are reformist, but that doesn’t mean they are not legitimate and that some women could not be won to a revolutionary position while struggling for those reforms. Women are not going to see proletarian revolution as being in their interest if the revolutionary movement does not prove itself in practice as being committed to the liberation of women by fighting male supremacy as part of the revolutionary process. No one is going to accept abstractions about equality under socialism if they can’t experience it in embryonic form during the course of the revolution.

At other times we did involve ourselves in these struggles and did put forward demands that were anti-racist and anti-imperialist. We think, though, that we often limited our effectiveness by creating our own forms of organization rather than working inside existent organizations. Even within our own “mass women’s organization”, we verbally  put forward a position about socialism being the only form of society in which women’s liberation could be achieved, but we did not consistently organize women to become revolutionaries. On the east Coast, at least, we did try to organize anti-imperialist women, but we did not struggle to build women as communists. An anti-imperialist women’s movement is part of a revolutionary strategy, but it does not substitute for the building of effective revolutionary communist organization.

put forward a position about socialism being the only form of society in which women’s liberation could be achieved, but we did not consistently organize women to become revolutionaries. On the east Coast, at least, we did try to organize anti-imperialist women, but we did not struggle to build women as communists. An anti-imperialist women’s movement is part of a revolutionary strategy, but it does not substitute for the building of effective revolutionary communist organization.

Analogously, we think that there are legitimate demands of white workers for better conditions, wages, employment, the right to organize. We think that some of us need to be involved in these struggles. We would struggle for these demands to be put forward in an anti-racist fashion, recognizing the need to fight white supremacy in the labour movement. It would be sectarian and self-defeating, though, to try to get the labour movement to put forward revolutionary demands in this period. Rather, we should simultaneously be organizing the most advanced workers into study groups, involving them in anti-imperialist activity outside the workplace, and organizing those who we can to be communists.

5) We changed the militarist conception that we had of our own organization. What we  mean by “militarist” in this context is that we saw ourselves as responsible only for doing as many military actions as we could; public organizations would be responsible for political organizing. Instead we define ourselves as a revolutionary organization with a political, organizational, and military strategy. Our military actions are designed to further our political goals and not to substitute for them. In this period, our military strategy includes acts of armed propaganda done by underground forces, illegal actions by aboveground clandestine groupings, and militant mass tactics. All of them are designed to strengthen resistance, promote anti-imperialist consciousness, and facilitate revolutionary organizing.

mean by “militarist” in this context is that we saw ourselves as responsible only for doing as many military actions as we could; public organizations would be responsible for political organizing. Instead we define ourselves as a revolutionary organization with a political, organizational, and military strategy. Our military actions are designed to further our political goals and not to substitute for them. In this period, our military strategy includes acts of armed propaganda done by underground forces, illegal actions by aboveground clandestine groupings, and militant mass tactics. All of them are designed to strengthen resistance, promote anti-imperialist consciousness, and facilitate revolutionary organizing.

6) The main internal work of our organization became the building of cadre. We were not going to be able to implement any part of our program without well-trained, self-reliant, and exemplary cadre. Obviously the military work demanded it, but so too does the mass organizing. Our movement, let alone our small organization, is tiny and not well situated for growth. Cadre need to be put into new areas of mass work alone or with only one or two other people: they need to figure out how to break with our history of rigid sectarianism on the one hand and avoid opportunism on the other. How to recruit someone clandestinely was something we all needed to figure out. Given our small size, every cadre needed to be exemplary and able to influence a number of other people. We thought of the example of Angel Cristobal of the LSP and the Vieques struggle. His militant practice, the clear political position he took as a POW in line with the development of the most advanced forces in the Independence Movement and his exemplary character enabled him to play a defining role in the Vieques struggle. The revolutionary sector of the Independence movement could not supply large numbers of cadres or extensive organizational resources, but through its cadre development was able to give political leadership.

We’ve found that a key part of becoming communist cadre is the struggle for ideology. We had studied for years but our dominant practice was to use bits and pieces of revolutionary writings as dogma to justify pre-existing positions. It’s been much different to try to become dialectical materialists and gain some objectivity on ourselves and on the world. We studied collectively and encouraged each other to pursue individual interests. Women cadre in particular struggled hard to overturn sexist stereotypes that make science and ideology “male domains”. It is both difficult and exciting to acquire the basics of dialectical and historical materialism; it is more difficult and more exciting to try to apply it to our own reality.

Ideology has been our major tool in the struggle to imbue ourselves and our organization with a revolutionary character. The struggles against personal and political opportunism, the struggle against the profound and manifold forms that individualism can take has been our most difficult and persistent fight. The “hothouse” effect of living in clandestinity may heighten these struggles, but they all existed for us prior to going underground. The struggle against racism and sexism did not disappear because we chose to be combatants; elitism and bad styles of leadership had to be overturned; arrogance and sectarianism had to be combatted.

A number of us thought that because we had decided to become guerrillas that we were revolutionaries. Well, we still believe that it was a revolutionary decision to make, but that there is a struggle every day to be a revolutionary. We have to be dialectical about ourselves: society is constantly changing; revolution is a process and not an event; revolutionaries have to change and grow every day to remain revolutionary. Complacency and bourgeois conceptions of prestige are antithetical to revolutionary morality. It is a real struggle to internalize dialectics, to recognize the need to change and even grow to thrive on it, to make criticism/self-criticism an objective and collective way to facilitate that growth and change. As soon as we get a stake in our “self-image” rather than contributing whatever we can to the revolutionary struggle, we know that we will begin to make subjectivist and opportunist errors.

We’ve had to deal a lot with the form of individualism that Santucho describes as self-sufficiency. Rather than building a real collective, the individual reserves to her/himself the right to supersede the collective judgement by their individual judgement. As long as the collective judgment and the individual’s agree, or as long as the collective is obviously correct, everything seems to be fine. It all breaks down in an emergency or when the correct answer is not apparent. Of course, that’s exactly when you need the most unified action. It’s clear that this is potentially disastrous in certain types of military work, but it’s damaging in all our work. We began to understand it as a reflection inside revolutionary organizations of the alienation in the dominant society of the worker from her/his labour: the organization becomes “other than oneself” even though the relationship is voluntary and the organization cannot exist without cadre.

The cadre are the heart of the organization; the revolutionary character of an organization resides in its cadre. This requires a correct line, but we’ve found that it also requires a very self-conscious plan for cadre development. In the past, our revolutionary organizations were little replica of bourgeois organizations with the cadre existing to support the leadership. We could read about the fact that for many years the People’s Liberation Army in China did not have special uniforms for officers, but we would still go ahead and create organizations where there was a qualitative difference between membership and leadership. leadership dealt with strategic issues and the cadre implemented them. Leadership issued general directives but rarely led the practice. Leadership even had petty privileges. It was all backwards, profoundly anti-democratic and anti-communist. It could only promote political backwardness and alienation among the cadre, and elitism and arrogance within the leadership. The membership decides and the leadership is empowered to lead the implementation of those decisions. It is the only basis for democratic centralism.

The cadre are the heart of the organization; the revolutionary character of an organization resides in its cadre. This requires a correct line, but we’ve found that it also requires a very self-conscious plan for cadre development. In the past, our revolutionary organizations were little replica of bourgeois organizations with the cadre existing to support the leadership. We could read about the fact that for many years the People’s Liberation Army in China did not have special uniforms for officers, but we would still go ahead and create organizations where there was a qualitative difference between membership and leadership. leadership dealt with strategic issues and the cadre implemented them. Leadership issued general directives but rarely led the practice. Leadership even had petty privileges. It was all backwards, profoundly anti-democratic and anti-communist. It could only promote political backwardness and alienation among the cadre, and elitism and arrogance within the leadership. The membership decides and the leadership is empowered to lead the implementation of those decisions. It is the only basis for democratic centralism.

A revolutionary organization needs a revolutionary program and cadre can only be built through struggling to implement it. But it’s vital that we remember that the embodiment of the program in the cadre her/himself. The masses experience the leadership of the organization through the practice and example of the cadre. Opportunist cadre will never be able to implement a revolutionary program, but revolutionary cadre will be able to note and struggle over any opportunist errors that arise in the line or program of the organization. A down to earth example that we experience all the time is the struggle to unite on the fact that we will not do a military action if we don’t think we can do it on a correct revolutionary basis. Any single action that we do in this period can only have a very limited impact on either the enemy or the anti-imperialist movement; however, it can have a major impact on us. By this, we don’t mean whether or not we can get away with it. We mean that if we do it well, it’s a significant step towards building our capacity on a revolutionary basis; if we commit opportunistic errors, or use cadre who are not really in a position to undertake the action, then we are building an opportunist practice. This is a qualitative difference, even thought the action looks the same to anyone else.

In this period, when revolution seems so distant and repression so real, each cadre has to explore his/her own revolutionary commitment. The sacrifices in going underground are real, and idealism and moralism don’t last too long; they can’t be replaced by the equally idealist notion that as individuals we will likely share in the eventual fruits of a socialist society. Many of us think back to something Don Juan said during one of his first visits: that he had always been a free man because he has fought for the freedom of his country. The joy for us has to be in the making of the revolution and not in the guarantee of our individual reward of socialism. To embrace the struggle for revolution fully means that we cannot see ourselves in any ways as victims or pawns. Our decisions must be our own, and we must take full responsibility for them. To the extent that we can feel a little of that freedom that Don Juan has talked about, we know that we will be capable of resisting anything that the state can do to us. To the extent that our movement understands that sense of freedom, we will be able to win others to want to make revolution and build a society based in real freedom.

In this period, when revolution seems so distant and repression so real, each cadre has to explore his/her own revolutionary commitment. The sacrifices in going underground are real, and idealism and moralism don’t last too long; they can’t be replaced by the equally idealist notion that as individuals we will likely share in the eventual fruits of a socialist society. Many of us think back to something Don Juan said during one of his first visits: that he had always been a free man because he has fought for the freedom of his country. The joy for us has to be in the making of the revolution and not in the guarantee of our individual reward of socialism. To embrace the struggle for revolution fully means that we cannot see ourselves in any ways as victims or pawns. Our decisions must be our own, and we must take full responsibility for them. To the extent that we can feel a little of that freedom that Don Juan has talked about, we know that we will be capable of resisting anything that the state can do to us. To the extent that our movement understands that sense of freedom, we will be able to win others to want to make revolution and build a society based in real freedom.

In our view, a program of support for armed struggle at this time would include:

1) Making the politics of the armed clandestine organizations accessible by reprinting all the communiques, reading them at demonstrations and forums, etc.

The armed organizations build their military infrastructure and do acts of armed propaganda to contribute to the entire movement and not just for their own organizations. Those communists who have access to public propagandizing should make that available to the armed movement. While the actions themselves get covered in the press (though the state clearly tries to suppress them), the content of the communiques obviously will not be disseminated by the New York Times and the Washington Post, nor will they likely be distributed by the opportunist “left” press like the Guardian. Especially in this very early stage, the armed clandestine organizations must rely on the sector of the anti-imperialist movement that has a principle of supporting armed struggle to put that into practice by reprinting all the communiques.

A position has emerged in the movement that it’s more correct for public communist organizations to reprint and distribute selected communiques. This position holds that its insecure for a public organization to reprint every communique because the public organization is then identified with the clandestine organization, or seen as speaking for it.

We disagree. We think that reprinting and distributing the writings of any organization is an act of support and solidarity, and of general agreement with the overall aims of that organization, not a sign of identity or complete unity. A communist organization that publishes all the communiques of an armed clandestine organization shows that it has the principle to give concrete form to its political support for the development of armed clandestine organization, and that it refuses to be deterred from doing so by fear of the state.

We are talking here about communists or other cadre organizations, not mass organizations. We think mass organizations should reprint and distribute those communiques that deal with their particular area of struggle. At this stage, it doesn’t seem right to us for mass organizations to make support for armed struggle in the oppressor nation a principle of unity. But we do think that communist organizations should.

We think communist organizations should reprint all the communiques of the armed clandestine organizations, whether those conform to their own political line or not.  Reprinting only those communiques that reflect a public organization’s line and program serves the needs of that organization, and is not synonymous with principled support for the building of armed struggle. In effect, when a communist organization chooses to print only those communiques that reflect its line, it is censoring the politics of the armed organization. This sort of censorship can unwittingly play into the state’s hands, because however good people’s original intentions may be, censoring the communiques helps the state implement its program of denial (denying support to clandestine forces). If the political statements of the armed clandestine organizations can’t reach the movement – and especially those sectors of the movement that would be most open to them – then the state has a much easier time of isolating armed clandestine forces, preventing us from playing a political role in the movement, and keeping our politics from the masses.

Reprinting only those communiques that reflect a public organization’s line and program serves the needs of that organization, and is not synonymous with principled support for the building of armed struggle. In effect, when a communist organization chooses to print only those communiques that reflect its line, it is censoring the politics of the armed organization. This sort of censorship can unwittingly play into the state’s hands, because however good people’s original intentions may be, censoring the communiques helps the state implement its program of denial (denying support to clandestine forces). If the political statements of the armed clandestine organizations can’t reach the movement – and especially those sectors of the movement that would be most open to them – then the state has a much easier time of isolating armed clandestine forces, preventing us from playing a political role in the movement, and keeping our politics from the masses.

Instead of being defensive in the face of the state’s attack on the revolutionary armed struggle as “terrorist”, we think communists in the public movement should see the reprinting of communiques as one form in which to combat legalism and fight the state’s attempts to constrain the revolutionary movement and isolate the armed clandestine organizations.

2) By dealing seriously with the politics of the armed clandestine organizations and responding to them.

This is an issue of basic respect and integrity. Organizations have emerged within the armed clandestine movement. They have politics and practice and they deserve to be dealt with as serious components of the revolutionary movement.

For example, when we issued our communique after we bombed the IAI, we made a criticism and argued that zionism and white supremacy were responsible for our movement’s failure to act in support of the Lebanese people when they were under attack by the U.S. and “Israel”. Comrades in the public movement did not respond to our criticism -either to accept or reject it, to agree with our analysis or to offer an alternative explanation for the lack of militant protest. We thought it was wrong for the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee to excerpt our communique in Death to the Klan, instead of printing the whole thing, as well as to choose not to respond to our criticism.

Altogether the armed clandestine organizations in the oppressor nation have only issued 19 communiques over the past 2 1/2 years. These communiques are a way for us to be in struggle with comrades in the public movement. In the communiques we take positions and raise political and strategic issues. Responding to these issues and positions is an important way to enable the armed clandestine organizations to participate in the political struggles raised by our actions.

3) By building cadre who want to be guerrillas.

The primary issue here is that any revolutionary movement has to build cadre who are willing and able to take up any of the tasks of that movement. For reformist organizations who condemn armed struggle, there is no issue of building cadre who would be ready to go underground and become guerrillas. In our sector of the movement, though, this has to be an integral part of cadre-building: the ability and readiness of any cadre to fight imperialism wherever she/he is needed.