Here, we’re publishing an interview by Sasha Lilley with Turbulence editors, Michal Osterweil and Ben Trott, from our 2010 book, What Would it Mean to Win? (PM Press): ‘A Conversation with the Turbulence Collective.‘

]]>

Here, we’re publishing an interview by Sasha Lilley with Turbulence editors, Michal Osterweil and Ben Trott, from our 2010 book, What Would it Mean to Win? (PM Press): ‘A Conversation with the Turbulence Collective.‘

In Issue 1, published in June 2007, Turbulence carried an interview with IWW members, Todd Hamilton and Nate Holdren, titled ‘Compositional Power‘. We are pleased to report that it has now been translated and published by the Dutch collective, Hydra Ensemble. It is available online here.

In Issue 1, published in June 2007, Turbulence carried an interview with IWW members, Todd Hamilton and Nate Holdren, titled ‘Compositional Power‘. We are pleased to report that it has now been translated and published by the Dutch collective, Hydra Ensemble. It is available online here.

The translation was published in Issue 3 of Hydra (October 2012), which can be read in full here.

‘How deep do the current political, economic, ecological and other crises run?’, ‘Why do the range of remedies on offer not seem fit for purpose?’, ‘What roles might recent movements – from the Arab Spring to #Occupy – play in finding ways out of this impasse?’, ‘What are the main challenges movements are confronted by, and how can they best be approached?’ These are just some of the questions Turbulence, a collective of activist-scholars, are exploring in their current research project. At this workshop – open to interested students, faculty and activists – some tentative answers will be presented for discussion.

‘How deep do the current political, economic, ecological and other crises run?’, ‘Why do the range of remedies on offer not seem fit for purpose?’, ‘What roles might recent movements – from the Arab Spring to #Occupy – play in finding ways out of this impasse?’, ‘What are the main challenges movements are confronted by, and how can they best be approached?’ These are just some of the questions Turbulence, a collective of activist-scholars, are exploring in their current research project. At this workshop – open to interested students, faculty and activists – some tentative answers will be presented for discussion.

The workshop is in four parts: ‘Nature and Causes of the Crises’; ‘Planning for the Anthropocene’; ‘Rethinking Realpolitik’; and, ‘A Politics of Problematics’. Each begins with a 15-minute input from a different member of the Turbulence collective, followed by around 35 minutes of open discussion.

Hosted by the Centre for the Study of Social and Global Justice (CSSGJ) at the University of Nottingham.

Wednesday 30 May, 12.00 – 16.00.

B2, The Hemsley, University of Nottingham. (Map here.)

www.turbulence.org.uk | http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/cssgj/

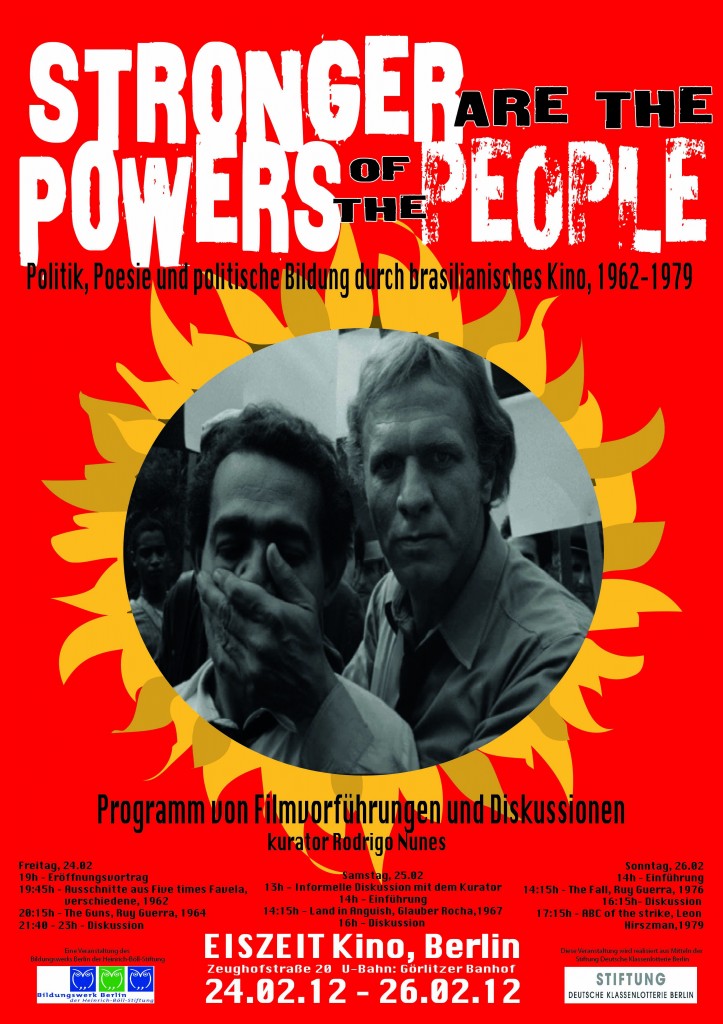

The following event has been curated by Turbulence editor, Rodrigo Nunes, and will take place in Berlin from 24-26 February.

EISZEIT Cinema, Berlin

24.02.12 – 26.02.12

A programme of film screenings and debates looks at Brazilian films from 1962-1979 in order to illuminate a rich time in the country’s life. Examining the period’s debates on the political valence of cultural work and the relations between art and politics serves as the starting point for a collective enquiry into the problems that animate artistic and political practice today – and what the past can teach us about them. The programme is curated by Brazilian philosopher Rodrigo Nunes.

‘Stronger are the powers of the people’: politics, poetics and popular education through Brazilian cinema, 1962-1979 uses six classic Brazilian films from the 1960s and 1970s as a guiding thread across the politics and culture of those years. While most of it was lived under a military dictatorship, the period was also one of the richest in the country’s cultural life. Then, the exploration of the intersections between art and politics were not only in an intense dialogue with what was taking place abroad, but also producing entirely original proposals: it was the time of the Centros Populares de Cultura (CPCs, or Popular Culture Centres), of Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, of Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed, of Neoconcretism, Tropicalismo, and Cinema Novo. Together, these experiments worked out solutions to a number of questions that are still pertinent today: what is the relationship between ‘popular’, ‘mass’ and ‘avant garde’ cutlure? what is the relationship between class and aesthetics? how do form and content relate in political art? what is (and should be) the professional and political status of engaged artists.

The films play the crucial role of being starting points for debate, but the goal is above all to generate a collective rethinking of the relationship between art and politics that can use those experiments from almost half a century ago to tackle the problems that animate political and artistic practice in the present.

The event consists of a film programme, with an opening lecture and an open debate (with invited respondents) at the end of each film. The films included are:

· segments from Cinco vezes favela (Five times favela), various directors, 1962

· Os Fuzis (The guns), Ruy Guerra, 1964

· Terra em transe (Land in a anguish), Glauber Rocha, 1967

· Dragão da Maldade contra o Santo Guerreiro (Antônio das Mortes), Glauber Rocha, 1969

· A Queda (The Fall), Ruy Guerra, 1976

· ABC da greve (ABC of the strike), Leon Hirszman, 1979-91

All films are in the original Portuguese with English subtitles.

Opening and introductory talks as well as discussions will be held in English

Friday

7pm – Opening talk: ‘Stronger are the powers of the people’ (45 minutes)

7.45pm – Screening of segments from Cinco vezes favela (Five times favela), various, 1962, 30 min

8.15 – 9.40pm – Screening of Os Fuzis (The guns), Ruy Guerra, 1964, 80min

9. 40 – 11.00pm – Discussion

Saturday

1pm – Informal discussion with the curator

2pm – Introductory talk

2.15pm – Screening of Terra em transe (Land in anguish), Glauber Rocha, 1967, 106 min

4pm – Discussion

4.45pm – End of day

Sunday

2pm – Introductory talk

2.15pm – Screening of A Queda (The Fall), Ruy Guerra, 1976, 120 min

4.15pm – Discussion

5pm – Break

5.15pm – Screening of ABC da greve (ABC of the strike), Leon Hirszman, 1979-90, 85 min

6.40pm – End of day

Cinco vezes favela (Five times favela), various authors, 1962

The only film the Popular Culture Centre (CPC) brought to completion, it comprises five episodes directed by Miguel Borges, Marcos Farias, Joaquim Pedro de Andrade, Caca Diegues, and Leon Hirszman, and was responsible for a split between the CPC and the cinema novo group. Some of the key figures in the CPC reportedly considered the film both a commercial and a political flop, and filmmakers such as Diegues and Arnaldo Jabor (though not Hirszman) left after decrying a narrow, instrumental conception of the relation between aesthetics and politics. With a cast including many of Augusto Boal’s colleagues from Teatro de Arena (and, most notably, CPC founder Oduvaldo Viana Filho), it captures a group of young filmmakers grappling with the same problems that were being felt in other areas – how to create a form adequate to the specificity of Brazilian content? How to do so in a way that reaches beyond a middle-class audience, and plays a role in the transformation of Brazilian society from below? What is popular culture, and how must the artist deal with it? – while working through a host of influences, from Russian revolutionary cinema to neo-realism. Joaquim Pedro de Andrade’s segment Couro de gato (Catskin) was included in a list of the 100 best shorts of all times selected by the Clermont-Ferrand Festival.

Os Fuzis (The guns), Ruy Guerra, 1964

One of the greatest achievements of the first crop of cinema novo – alongside Nelson Pereira dos Santos’ Vidas secas (Barren lives) and Glauber Rocha’s Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol (Black God White Devil) (1964) –, it showcases many of the period’s defining traits: the rural Northeastern setting, the use of location, natural light and non-professional actors. At the same time, in its plot about the existential and moral crises undergone by a group of soldiers sent to a small town to stop the starving victims of the draught from attacking a food warehouse, it provides in arguably the clearest way the keys to reading some of the political limitations of cinema novo at this stage. It won the Silver Bear at the Berlin Festival.

Terra em transe (Land in anguish), Glauber Rocha, 1967

Part roman à clef about the Joao Goulart government and the 1964 military coup, part schematic description of the dynamics of the post-colonial world, part baroque allegory about the destiny of Latin America, part gauntlet thrown at the right and left of post- coup Brazil: one of Rocha’s most celebrated films, it finds the effects of his ‘epic-didactic’ cinema all the more effective because its target is much clearer. A whole generation at a crossroads appears in the vacillations of the main character, his multiple allegiances to social transformation and to his own class, to aesthetics and to politics, to utopia, the heat of the struggle, and his professional situation as a hired pen. The choice for armed struggle, which the film suggests in ambiguous fashion, was already brewing as it was produced. Nominated to the Palme d’Or at Cannes, best film at the Havana Film Festival.

O Dragão da Maldade contra o Santo Guerreiro (Antônio das Mortes), Glauber Rocha, 1969

Rocha’s first international co-production, first film in colour, and first using direct sound. He would often refer to it as ‘my western’, but, despite some nods at John Ford and Howard Hawks, it is clear that the oeuvre in question here is above all his own. Like a revision of his two earlier films that relaunches its questions, but also seems to run out of answers, it already points towards some of the procedures (such as the long, semi-improvised takes) that would characterise his work in the exile that immediately follows it. The plot finds Antônio das Mortes, the gunman hired by landowners to kill cangaceiros (highwaymen), brought out of retirement for one last job which, once executed, causes him to question the side on which he has fought over the years. Won best director and a nomination to the Palme d’Or at Cannes.

A Queda (The Fall), Ruy Guerra, 1976

An accident at a construction site, resulting in one death, sets one worker off on a struggle for justice that exposes the mechanisms of exploitation and the class relations of a country that had undergone one decade of fast-paced ‘conservative modernisation’ at the hands of the military. As a sort of sequel to the classic The Guns (1964), following the fate of those characters as they move from enforcers of exploitation to exploited, it offers more than a snapshot of the period: the correspondent time lapses in fiction and reality capture the passage of a chunk of Brazilian history between the two films, and, therefore, also the transformations in cinematographic approaches to the social and political between the two moments. Equally daring in content and form, and in the originality of the adequacy of one to the other, it won the Silver Bear at Berlin.

ABC da greve (ABC of the strike), Leon Hirszman, 1979-91

While preparing the cinema version of Teatro de Arena’s groundbreaking 1957 play Eles não usam black tie on location in the ABC (the auto industry belt around São Paulo), Hirszman has the opportunity to document the most important strike in over a decade of Brazilian history. The latter would become a catalyst and a convergence point for the opposition to the military regime, intellectuals, artists, returning exiles, eventually leading to the creation of the Worker’s Party – whose biggest leader, Lula, was the president of the metalworkers union who led the strikes. Running into problems with the regime’s censorship because of the material, Hirszman dies in 1987 leaving the film unfinished until 1991, when his two daughters and son eventually release a final cut. The narration and text are provided by Ferreira Gullar, poet, who was president of the CPC at the time of the military coup.

This event is organised by the Heinrich Böll Foundation’s Educational Institute in Berlin. It is made possible through the funding of the Stiftung Deutsche Klassenlotterie Berlin.

The event is free.

Venue: EISZEIT Kino Zeughofstr. 2010997 Berlin (www.eiszeitkino.de)

With the #OccupyEverything movement spreading, we would have loved to have been able to drop off copies of the magazine for folks to read – especially with libraries popping up at occupations in New York, London and elsewhere. But we can’t get copies everywhere, and issues 1, 3 and 4 are out of print anyway. So here, perhaps, is the next best thing… By clicking here, you can download a PDF flyer. If it takes your fancy, print it off, make a few copies and drop them off at any occupation you visit. The flyers have a QR (or Quick Response) code on them, which smart-phones can read. Just scan them using a free QR reader/scanner (like this one) and a Turbulence back issue will be downloaded straight to your phone. Free, of course. It’s the best way we could think of making copies widely available, on-site and at no cost.

With the #OccupyEverything movement spreading, we would have loved to have been able to drop off copies of the magazine for folks to read – especially with libraries popping up at occupations in New York, London and elsewhere. But we can’t get copies everywhere, and issues 1, 3 and 4 are out of print anyway. So here, perhaps, is the next best thing… By clicking here, you can download a PDF flyer. If it takes your fancy, print it off, make a few copies and drop them off at any occupation you visit. The flyers have a QR (or Quick Response) code on them, which smart-phones can read. Just scan them using a free QR reader/scanner (like this one) and a Turbulence back issue will be downloaded straight to your phone. Free, of course. It’s the best way we could think of making copies widely available, on-site and at no cost.

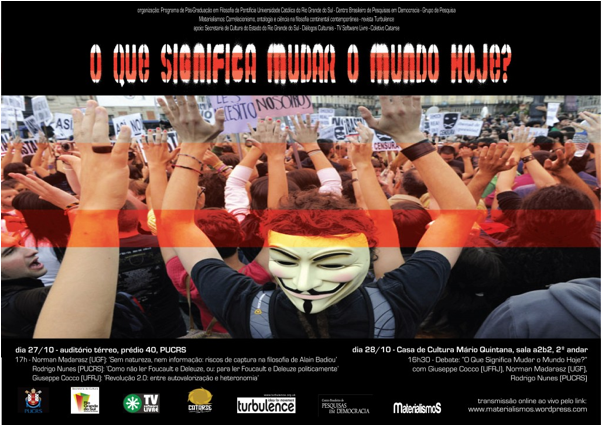

Turbulence editor Rodrigo Nunes will take part in a debate called What does changing the world mean today? in Porto Alegre, Brazil. Also in the debate, which is part of a two-day seminar by the same name, will be Giuseppe Cocco and Norman Madarasz. The debate, in Portuguese, can be watched online at www.materialismos.wordpress.com on October 28th, 4.30pm (Brasília time).

Turbulence editor Rodrigo Nunes will take part in a debate called What does changing the world mean today? in Porto Alegre, Brazil. Also in the debate, which is part of a two-day seminar by the same name, will be Giuseppe Cocco and Norman Madarasz. The debate, in Portuguese, can be watched online at www.materialismos.wordpress.com on October 28th, 4.30pm (Brasília time).

PORTUGUESE TRANSLATION: Rodrigo Nunes, editor de Turbulence, participará de um debate chamado O Que Significa Mudar o Mundo Hoje? em Porto Alegre, Brasil. Giuseppe Cocco e Norman Madarasz serão os outros participantes do debate, que é parte de um seminário de dois dias com o mesmo tema. A discussão, em português, poderá ser vista ao vivo em www.materialismos.wordpress.com a partir das 4.30pm (horário de Brasília) do dia 28/10.

All you need is a QR (or Quick Response) code scanner app, widely available for free. (For the iPhone or iPad 2, for example, you can download the ‘QR Code Reader and Scanner’ app by ShopSavvy, Inc for free here. Similar apps are easily available for the Android, Blackberry and other phones and tablets.)

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

On 15th October 2011, united in our diversity, united for global change, we demand global democracy: global governance by the people, for the people. Inspired by our sisters and brothers in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Syria, Bahrain, New York, Palestine-Israel, Spain and Greece, we too call for a regime change: a global regime change. In the words of Vandana Shiva, the Indian activist, today we demand replacing the G8 with the whole of humanity – the G 7,000,000,000.

Undemocratic international institutions are our global Mubarak, our global Assad, our global Gaddafi. These include: the IMF, the WTO, global markets, multinational banks, the G8\G20, the European Central Bank and the UN Security Council. Like Mubarak and Assad, these institutions must not be allowed to run people’s lives without their consent. We are all born equal, rich or poor, woman or man. Every African and Asian is equal to every European and American. Our global institutions must reflect this, or be overturned.

Today, more than ever before, global forces shape people’s lives. Our jobs, health, housing, education and pensions are controlled by global banks, markets, tax-havens, corporations and financial crises. Our environment is being destroyed by pollution in other continents. Our safety is determined by international wars and international trade in arms, drugs and natural resources. We are losing control over our lives. This must stop. This will stop. The citizens of the world must get control over the decisions that influence them in all levels – from global to local. That is global democracy. That is what we demand today.

Today, like the Mexican Zapatistas, we say “¡Ya basta! Aquí el pueblo manda y el gobierno obedece”: Enough! Here the people command and global institutions obey! Like the Spanish Tomalaplaza we say “Democracia Real Ya”: True global democracy now!” Today we call the citizens of the world: let us globalise Tahrir Square! Let us globalise Puerta del Sol!

Follow it on Facebook: http://facebook.com/g7billion | Discuss it on Twitter with the hashtag #globaldemocracy | @G7billion

Supporting organisations, assemblies and writers so far: General People’s Assembly Puerta del Sol – Madrid | People’s Assembly London | People’s Assembly Buenos Aires | People’s Assembly Sao Paulo | People’s Assembly Vigo | Spain People’s Assemblies Network | People’s assembly Boston | Occupy Melbourne | ATTAC Spain | ATTAC France | War on Want – London | Globalise Resistance – London | Italy Uncut | Democracia Real Ya International | Gaia Foundation | Egality London | Egality Berlin | Network Institute for Global Democratization | Naomi Klein | Vandana Shiva | Noam Chomsky | Eduardo Galeano | Michael Hardt | Turbulence

If your organisation or assembly wishes to sign the statement, or you are an individual who wishes to show support, please add comments to the wall or email G7billion@gmail.com or twitter @G7billion

Only the naivest ‘state socialist’ would expect the process that went from being movement to becoming government to be without friction, fractiousness and confrontation. At the same time, one should avoid making what is specific about each situation disappear in the ready-made schemas that it is so easy to fall back on. Take the environmental conflicts that have flared up in recent years: rather than simply opposing ‘modernising, Westernising’ government to an ‘indigeneity’ that only wants to ‘live in harmony with nature’ – merely a well-meaning continuation of the colonial distinction between Western ‘culture’ and indigenous ‘nature’ –, the story these conflicts tell is much more complex. Bolivia is the poorest country in Latin America, with an infrastructure that does not meet the needs of its population; in many cases, movements have demanded more, not less, ‘development’. The problem is rather: what kind of development, for whom, in whose land and decided through which channels of democratic participation?

Rather than the immediate fulfillment of every demand put to them, what one should expect of governments with such a close tie to social movements is transparency, openness to debate and the humility to understand that their role, despite being different in its functions, is just one more within a process of change: a partner in a pedagogic process of transformation, with a special responsibility when it comes to keeping it alive. In this regard, it is hard not to notice that, since Morales’ re-election and MAS’ attainment of a clear majority in parliament, things have taken a turn for the worse. Dialogue has become more difficult, interlocutors have been selected to reinforce the government’s position, and clientelistic relations that help impede the renewal of movement leadership have developed. The government’s refusal to establish a proper debate around the TIPNIS issue (see below), or even to follow national and international rules on consulting the local population, is a sad new episode in what has recently become more and more common. The violent repression of the TIPNIS march by the police on September 25th, however, marks a new low that cannot but recall the incidents that led to the fall of previous presidents Sánchez de Lozada and Carlos Mesa. (For more, see: 1 | 2 | 3.)

We republish below a statement from Jim Shultz, director of the Democracy Center, based in Cochabamba. Over the years, Shultz has played an important role in ‘translating’ Bolivian politics to the English-speaking world, having been the first to break the news of the Water War outside Bolivia.

– Turbulence collective, October 2

by Jim Shultz, director of the Democracy Center

In 2005, Sacha Llorenti, the President of Bolivia’s National Human Rights Assembly, wrote a forward for our Democracy Center report on an incident here two years previously, known as ‘Febrero Negro’. The IMF had demanded that Bolivia tighten its economic belt and President Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada complied by proposing a new tax on the poor. His action set off a wave of protest and government repression that left 34 people dead. Llorenti wrote of the government’s repression, “Those days refer to an institutional crisis, state violence, and her twin sister, impunity.”

In 2005, Sacha Llorenti, the President of Bolivia’s National Human Rights Assembly, wrote a forward for our Democracy Center report on an incident here two years previously, known as ‘Febrero Negro’. The IMF had demanded that Bolivia tighten its economic belt and President Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada complied by proposing a new tax on the poor. His action set off a wave of protest and government repression that left 34 people dead. Llorenti wrote of the government’s repression, “Those days refer to an institutional crisis, state violence, and her twin sister, impunity.”

Only months after Llorenti wrote those words, that era in Bolivia’s history seemed swept away in a wave of hope. The nation’s first indigenous President, Evo Morales, rode into power on a voter mandate unmatched in modern Bolivian history. He proclaimed a new Bolivia in which indigenous people would take their rightful place in the nation’s political life, human rights would be respected, and a new constitution would guarantee autonomy for communities ignored by the governments of the past. Overnight the people who had been attacked or ignored by Bolivia’s leaders suddenly became Bolivia’s leaders. Llorenti eventually rose to the most powerful appointed position in the nation, Minister of Government. The rays of optimism that spread out from Tiwanaku and La Paz extended worldwide and Morales become a global symbol of something hopeful.

It is a sad measure of how deeply things have changed that it was Llorenti himself who stepped behind the podium at the Presidential Palace last Monday to defend the Morales government’s violent repression of indigenous protesters on September 25th. Five hundred police armed with guns, batons and tear gas were sent to a remote roadside to break up the six-week-long march of indigenous families protesting Morales’ planned highway through the TIPNIS rainforest. Llorenti’s declarations echoed the tired justifications heard from so many governments before: “All the actions taken by the police had the objective of preventing conflicts and if cases of abuse have been committed they will be punished.”

Men, women and children marching to defend their lands were attacked with a barrage of tear gas, their leaders were beaten, women had bands of tape forcibly wrapped over their mouths – all under orders from a government that had promised to be theirs. How did it come to this?

The Highway Through the Rainforest

The indigenous families that were attacked by police on that Sunday left their lands in the TIPNIS on August 15th to march nearly 400 miles to their nation’s capital and press their case against the road that would cut through the heart of their lands. President Morales had made it very clear that he was not interested in hearing any more of their arguments against the mainly Brazil-financed highway. In June he declared, “Whether you like it or not, we are going to build this road.”

Morales argued that the highway was needed for “development,” creating new economic opportunities in parts of the country long isolated. In the name of those goals he was willing to ignore the requirements of community consultation and autonomy in the new Constitution that he had once championed. He was willing to abandon his own rhetoric to the world about protecting Mother Earth and to ignore studies about the likely destruction of the forest that the new highway would bring. What could have been a moment of authentic and valuable debate in Bolivia about what kind of development the nation really wanted instead became a series of presidential declarations and decrees.

As the march of some 1,000 people crept slowly onward toward La Paz its moral weight seem to grow with each step, drawing growing public attention that Morales couldn’t stop. The march became the lead story in the country’s daily papers every morning for weeks. Civic actions in support of the marchers grew in Bolivia’s major cities. More than sixty international environmental groups, led by Amazon Watch, signed a letter to Morales asking him to respect the marchers’ demands.

From Morales, however, each day only brought a new set of accusations aimed at stripping the marchers of their legitimacy. First, said the government, the march was the creation of the U.S. Embassy. Then the government declared that the marchers were the pawns of foreign and domestic NGOs. Last week while in New York for his speech to the U.N., the Morales entourage announced that it had evidence that it was former President Sanchez de Lozada who was behind the march. The litany of ever-changing charges began to sound something akin to a schoolboy scrambling to invent reasons for why he didn’t have his homework.

When the charges failed to derail the marchers’ support, the government and its supporters decided to try to steer them off their path to La Paz in other ways. They blocked the arrival of urgent donations of water, food, and medicine gathered and sent from throughout the country. But this only added yet again to the moral weight of humble people walking the long road to the capital.

Tear Gas at Dusk

Just after 5pm on Sunday, September 25, five hundred police dressed in full battle gear descended on the encampment where the marchers had pitched themselves for the night. Running at full speed they began firing canisters of toxic tear gas directly into the terrified groups of men, women, and children. Then the police began forcing them, screaming and crying, onto buses and into the backs of unmarked trucks for unknown destinations. Television footage captured the police knocking women to the ground and binding their mouths shut with tape. Many others ran to escape into the trees and fields so far from their homes. Children were separated from their parents.

Later that night those who had escaped the police began to take refuge in the small church of the town of San Borja. Early Monday morning government planes tried to land on an air strip in the town of Rurrenabaque, where more than 200 captured marchers were to be forcibly put aboard and returned to the villages where they had begun their trek so many weeks and miles before. The people in the community swarmed the runway to keep the planes from landing and were met with another attack of tear gas by the police sent there by the government.

Hours later the country’s young Defense Minister, Cecilia Chacon, announced her resignation. She wrote in a public letter to President Morales, “I can not defend or justify it [Sunday’s repression]. There are other alternatives in the framework of dialogue, respect for human rights, nonviolence, and defense of Mother Earth.”

She became the latest in a string of former Morales allies who had dramatically split from the government over the TIPNIS highway and the government’s abuses of the marchers. Morales’ former ambasador to the U.S., Gustavo Guzman, and the President’s former Vice-Minister for Land, Alejandro Almaraz, had not only left the government but also gone to join the marchers.

Over the course of the following Monday public denouncements poured out against the police attack on the marchers – from the National Public Ombudsman, the U.N., women’s groups, human rights groups, the Catholic Church, labor unions, and others, including many who had once been fervent Morales supporters.

By that Monday evening, with his public support in freefall, Morales finally spoke to the nation. He began by denying any involvement in Sunday’s police violence, blaming it on unnamed subordinates. But after years of arguing that his predecessors should be prosecuted for the abuses of soldiers and police under their command, it was a defense that convinced no one. Several key government officials told journalists that such an aggressive police action would never have taken place without orders from the government’s highest ranks.

Morales then announced that he would put the highway to a vote by the two Bolivian states, Cochabamba and Beni, through which the project would pass. Almaraz, the former Lands Vice-Minister, and others, quickly pointed out that such a referendum was unconstitutional, a direct violation of the provisions allowing local indigenous communities to decide the fates of their lands.

If Morales thought he had plugged the political leak in his weakened Presidency, it became clear Tuesday morning that the anger against him was only growing. Larger marches filled the streets in the cities of La Paz, Cochabamba, Santa Cruz and Sucre. The country’s labor federation (C.O.B) announced a strike. By nightfall the nation’s transportation workers announced that they too would stage a work stoppage Wednesday in opposition to the highway and in support of the marchers.

Just after 7pm Tuesday night Sacha Llorenti appeared at the Presidential Palace podium once again, this time to announce his own resignation. It appeared not so much an act of conscience, in the mold of Ms. Chacon’s the day before, but more a man being tossed overboard in the hope that it might afford the President some political protection.

Then Morales took to the airwaves to add an announcement of his own – the temporary suspension of construction of the disputed road. But by early Wednesday news reports revealed that the Brazilian firm happily bulldozing the highway had received no such order.

A People Rising

Wednesday morning Evo Morales woke to a nation headed for a transit standstill, with new marchers headed to the streets, schools closed and a nation deeply angry with its President. The cheering crowds of his 2006 inaugural had become a distant memory.

What is behind Morales’ devotion to a road through the heart of the TIPNIS? Is he simply a stubborn believer in a vision of economic development filled with highways and factories, in the style of the North? Is it a matter of Presidential ego, of not wanting to make the call to his Brazilian counterpart (Brazil is both the financier and constructor of the road, and eager to gain access to the natural resources it would make accessible), admitting that he can’t deliver on a Presidential promise? Are his deepest supporters, the coca growers, so anxious for a road that will open up new lands for expanding their crop that Morales has been willing to push things this far? Only President Morales knows his true motivations. But what is a certainty is that he has paid an enormous political cost for sticking to them.

The events of the past week represent something new rising in Bolivia. The people – who have now listened to many Morales speeches about protecting the Earth and guaranteeing indigenous people control over their lands – have risen to defend those principles, even if their President has seemingly abandoned them. Ironically, Morales has now inspired a new environmental movement among the nation’s younger generation, not by his example but in battle with it.

In my interview with Sacha Llorenti for our report on Febrero Negro, he also told me something else. He told me that the 2003 repression was, “the moment in which the crisis of the country was stripped down to the point where you could see its bones.” Today in Bolivia a different crisis has laid bare a new set of political bones for all to see.

Evo Morales, in his global pulpit, had been an inspiring voice, especially on climate change and on challenging the excesses of the U.S. In Bolivia on economic matters he has often been true to the world, raising taxes on foreign oil companies and using some of those revenues to give school children a modest annual bonus for staying in the classroom.

But the abuses dealt out by the government against the people of the TIPNIS have knocked ‘Evo the icon’ off his pedestal in a way from which he will never fully recover, in Bolivia and globally. He seems now pretty much like any other politician. What has risen instead is a movement once again of the Bolivian people themselves – awake, mobilized, and courageous. The defense of Bolivia’s environment and indigenous people now rests in the hands, not of Presidential power, but people power – where real democracy must always reside.

[Source: http://democracyctr.org/blog/archives/1636, 28 September 2011]

With Rodrigo Nunes

Tuesday 20 September, 2011. 7.00pm

Evo Morales’ electoral victory in Bolivia in 2005 came on the back of a decade of growing mobilisation among urban and rural social movements, especially indigenous. In itself, the fact that his candidacy managed to count on most of these movements’ support is directly tied to a public commitment to turn a common agenda presented by the latter into his government programme. Movement leaders have been largely represented in cabinet and other government positions. Yet today, after the first term of the proceso de cambio (transformation process) and Morales’ re-election, the tensions in this relationship and its limits seem not only more evident, but also on the rise. This talk offers a genealogy of the network of relations that constitute the proceso de cambio, the dynamics that have conditioned it, and the lessons that can be drawn from the Bolivian case for the age-old question of how movements (should) relate to institutions.

More info: http://www.bildungswerk-boell.de/calendar/VA-viewevt.aspx?evtid=10276&returnurl=/index.html

With Michal Osterweil

Monday 26 September, 2011. 7.00pm

In recent years many have criticized the politics of the so-called alter-globalization movement suggesting that its emphasis on a “new politics” characterized by horizontality, difference and reflexivity made it unable to act in a coherent or organized way. However, Osterweil argues that the call to return to a more pragmatic, party-like politics is itself premised on a false diagnosis of the nature of the problem – a problem that has to do with a larger crisis of Liberal Modernity and the ways of knowing, being and doing linked to it. Based on work with movements in Latin America and the US, Osterweil suggests that only politics that confront the deeply entrenched cultural logics and worldviews at play will we be able to move beyond the current political crises.

More info: http://www.bildungswerk-boell.de/calendar/VA-viewevt.aspx?evtid=10293&returnurl=/index.html

Both events will be chaired by Turbulence: Ideas for Movement editor, Ben Trott. They are organised by the Heinrich Böll Foundation’s Educational Institute in Berlin and have been made possible through the funding of the Stiftung Deutsche Klassenlotterie Berlin.

The events are free. Registration is requested, but is not compulsory. Please email: global@bildungswerk-boell.de

Location: Bildungswerk Berlin der Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, Kottbusser Damm 72, 10967 Berlin (U-Bahnhof Hermannplatz).

Map: http://www.berlinonline.de/citymap/map.asp?ADR_ZIP=10967&ADR_STREET=Kottbusser+Damm&ADR_HOUSE=72