Anti-Fascism and Racial Struggle in Song

By Meredith Holmgren, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

The events that unfolded last month in Charlottesville, Virginia, when neo-fascist protests against the removal of a Confederate monument escalated to the deaths of three persons, have stirred nationwide debate about the history of fascism and white supremacy. Lonnie G. Bunch III, the director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture soon issued a statement reminding us that this incident was only the most recent example of “a long legacy of violence intended to intimidate and marginalize African Americans and Jews.” One aspect of this legacy, he wrote, was the construction of Confederate monuments in the mid-twentieth century, which many saw as a backlash to the U.S. civil rights movement.

Monere, the Latin root of “monument,” means to remind, to warn. In some ways, music recordings and archives are also like monuments—they too have the power to remind and to warn. As someone who works with Smithsonian Folkways’ large collection of music and sound from around the world, these events have prompted me to reflect on how Folkways’ musicians have historically responded to fascism and racial struggle. What reminders and warnings do the musicians in our collections express to us today?

![By Al Aumuller/New York World-Telegram and the Sun (uploaded by User:Urban) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](/web/20190202062552im_/https://folkways.si.edu/images/explore_folkways/peoples-picks/Woody_Guthrie.jpg)

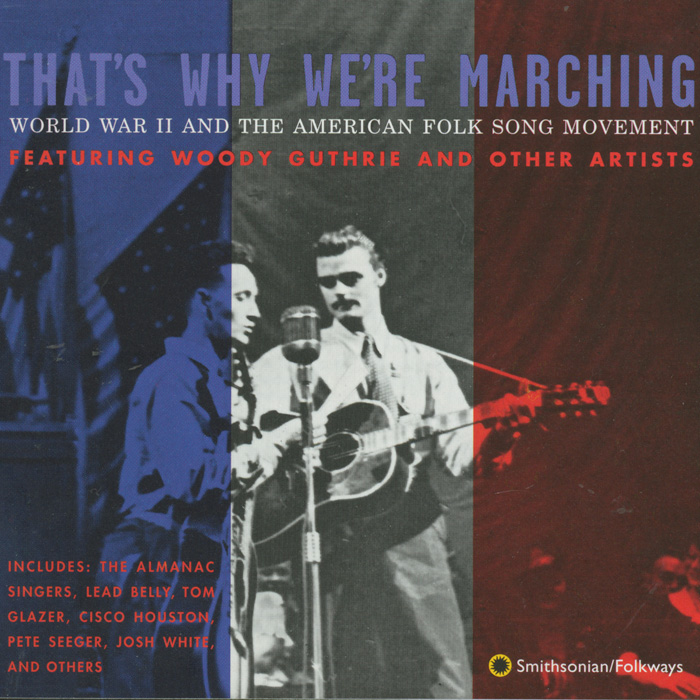

One of Smithsonian Folkways’ best known recording artists, Woody Guthrie, famously placed the message “This Machine Kills Fascists” on his guitar in 1941, in the midst of the Second World War. “Though initially against WWII, Guthrie served as a Merchant Marine and sang in support of the war effort,” writes Jeff Place in this Artist Spotlight. In examining Guthrie’s catalog, one will notice that his numerous songs against fascism not only tackle it as a political ideology, but conceptually extend it to the economic realm, often placing fascism and trade unions in binary opposition. “This conceptualization of fascism as a form of slavery which… particularly aims at economic exploitation of the labor force, also allows Guthrie to provide a solution to the fascist problem, which, quite logically, lies in the organization of the collective work force in labor unions,” writes John S. Partington in his 2011 book The Life, Music and Thought of Woody Guthrie: A Critical Appraisal.1

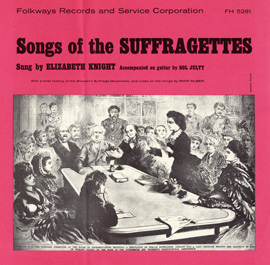

Whether issued as political critique or socioeconomic empowerment, the message that Guthrie placed on his guitar clearly conveys his belief in the power of music to counter inequality and fascist ideology. Like Guthrie, Folkways Records cofounder Moses Asch also believed in the power of song. As a Polish Jewish immigrant, whose family experienced racial intimidation in Europe, Asch documented the music of numerous Holocaust survivors, Spanish Civil War veterans, and civil rights activists as part of his “encyclopedia of sound” that the Folkways catalog came to be known for.

Several other collections that are a part of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings also speak to the social power of music. Barbara Dane and Irwin Silber, founders of Paredon Records, specialized in publishing music that represented “the worldwide struggle for economic, racial, and social justice and national liberation.” Joe Glazer, musician and founder of Collector Records, focused his label on musics of the U.S. labor movement and recorded songs of the American Civil War to tell stories of abolition and national unity. Roberto Martínez, founder of Minority Owned Record Enterprises (M.O.R.E.), cited racial discrimination as a motivating factor in his documentation of Mexican heritage musics. “His corridos (story songs) praised cultural resistance in the face of social injustice and instilled patriotic pride in Mexican Americans,” writes Daniel Sheehy in his 2013 tribute to Martínez.

The following playlist digs into the Smithsonian Folkways collections to investigate these recordings. The compilation is sequenced in rough historical form, starting with songs of the Spanish Civil War before moving through WWII, the civil rights movement, anti-apartheid, neo-fascism, and finishing with a reflection on the state of cultural equity in the 1980s. The narratives that accompany each track seek to situate each song within the historical context that they were written or performed. The compilation below represents but a small sampling of these songs from our collections.

“Jarama” honors the experiences of American volunteers in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade who fought against General Francisco Franco’s takeover of Spain during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). Backed by Benito Mussolini, Adolf Hitler, and Moroccan Regulares, Franco’s nationalists attempted to capture the Spanish capital of Madrid by crossing republican lines in the Jarama river valley in 1937. After a bloody battle that caused heavy casualties on both sides, the brigades emerged successful in holding the line. Although the republicans won the Battle of Jarama, they eventually lost the war to Franco in 1939, which ushered in several decades of military dictatorship. Guthrie’s version of this song looks back on the Battle of Jarama in 1944, long after the war was lost, to honor the brigades, and speak of hope for “[setting] this valley free before we’re through.”

This song was officially banned in Spain until after Franco’s death in 1976.2 However, on Spain in My Heart: Songs of the Spanish Civil War (Appleseed, 2003), Pete Seeger details how Folkways recordings of this song were smuggled into Spain on tape throughout the Franco period. Because of these tapes, many Spaniards had already memorized the song by the time Seeger performed it to Spanish audiences across the country in 1978.

“Freiheit” is a song about the Thälmann Battalion, a German division of the International Brigades that fought with republican forces during the Spanish Civil War. Having already lost their own country to Hitler rule, this brigade, which was composed mostly of working-class Germans and Austrians, was determined to keep fascism from spreading throughout Europe. Written by Paul Dessau and Gundrn Kabish, the song launched to infamy when it was recorded by German folk singer and actor Ernst Busch, who appears alongside Pete Seeger on Songs of the Spanish Civil War, Volumes 1 & 2.

Written in 1942 by Langston Hughes and Emerson Harper, “Freedom Road” links the struggle against Nazi fascism abroad to the fight for racial equality at home in the United States. While many African Americans served with distinction during the war, they often did so in segregated military units. It was not until 1948, three years after the end of WWII, that an executive order was signed by President Harry Truman to officially desegregate the military. The liner notes express how “Josh White referred to this song as a ‘rousing plea for true democracy’, which for him was a democracy with no color line.”

Composed and recorded in 1942 during the height of World War II, this song chronicles the rise of Hitler in Germany and predicts his eventual fall at the hands of American forces. During the war, Lead Belly registered for the draft, but at 53 years old, he was never called upon to serve. The song starts slow and gradually builds into a chorus of ferocity: “We’re gonna tear Hitler down!” Echoing a line from the old blues song “I’m Going to Tear Your Playhouse Down,” Lead Belly can also be heard singing “Hitler, we’re gonna tear your playhouse down.”

“Why Need We Cry?” is a powerful testament to survival and resilience in the face of genocide. Cantor Abraham Brun, a Polish Jewish Holocaust survivor, presents this song from the Łódź Ghetto. It declares that Jewish people will persevere and emerge victorious in the face of Nazi fascism. It’s a remarkable song that encourages people to not despair, but celebrate survival. Of the album, Moses Asch, cofounder of Folkways Records and himself a Polish Jewish immigrant, writes: “We deem it our duty to record these songs, so that they may not be forgotten.”

Perhaps the most recognizable anti-fascist song worldwide, “Bella Ciao” was originally sung by Italian partisans (partigianos) who fought in the resistance movement during WWII. Because Mussolini’s Italy is widely regarded as the birthplace of fascist government, the song serves as a potent reminder of the resistance movements that grew alongside the political ideology. Over the years, “Bella Ciao” has been performed in numerous languages and adapted to a variety of contexts, including pro-democracy demonstrations and labor movements.

After witnessing the power of the Albany Movement, which was among the first mass mobilizations to advocate for total desegregation, Pete Seeger suggested that a singing group be formed to raise money for the burgeoning Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Thus, The Freedom Singers were born. Founded by Cordell Hull Reagon, Bernice Johnson and others, this group traveled across the country to spread information about civil rights struggles and raise money for the SNCC. Based on the spiritual “Don't You Let Nobody Turn You Around,” this song was first adapted for civil rights during the Albany Movement, which is where this particular track was recorded in 1962. It demonstrates some of the hallmark traits of protest music from that era, including call and response, group harmony, and improvisation.

During the U.S. civil rights movement, one of the many creative methods for getting a message across was to ascribe new lyrics to popular tunes. The Nashville Quartet, comprised of four students from the American Baptist Theological Seminary, became well known for using pop music in their repertoire. In 1956, Little Willie John released a song titled “You Better Leave My Kitten Alone,” which had a fairly predictable narrative about love and jealousy (and was later popularized by the Beatles). The Nashville Quartet reconfigured the lyrics in 1960 to be about segregation and resistance to change, which resulted in the catchy yet poignant “You Better Leave Segregation Alone.”

Derived from the African American spiritual “I Shall Not Be Moved,” “We Shall Not Be Moved” was popularized by the U.S. labor and civil rights movements of the early- to mid-twentieth century. Once it was translated to Spanish, “No nos moverán” was picked up in Spain by those opposing Franco. Joan Baez famously played it on live Spanish television in 1977, where it had been banned for the previous forty years, and dedicated the performance to republican hero Dolores Ibárruri.3 The song also made its way to Chile, where it was popularized by socialist reformers and nueva canción performers. During Augusto Pinochet’s military overthrow of President Salvador Allende, the only radio station to finish airing Allende’s final speech subsequently closed its broadcast with “No nos moverán.”4

Recorded in the early 1960s, at a refugee camp for South Africans in the newly-independent state of Tanganyika (present-day Tanzania), this track is a powerful testament to the early African anti-apartheid movement. The singers were loosely affiliated with the African National Congress, which, as the largest anti-apartheid political party at the time, served many refugees across the region. The lyrics are simple but strong in their message: Black Africans will prevail in the fight against apartheid. In this song, apartheid is personified in Henrik Verwoerd, who is often referred to as the “Architect of Apartheid” for his instrumental role in implementing and expanding apartheid policy during the 1950s and 60s. Although Verwoerd was assassinated in 1966, apartheid remained official national policy until the 1990s.

Released in 1969, during the neo-fascist Greek military junta (1967–1974), “The Boy with the Sunlit Smile” served as the theme song for Z, an Academy Award-winning political thriller that is based on the real-life assassination of Grigoris Lambrakis. Lambrakis—a WWII hero, peace activist, free clinic doctor, and politician—served in the Greek parliament until he was publicly murdered by neo-fascists in 1963. The trial and investigation surrounding his assassination were subject to hot political debate, both at home and abroad. Musician Mikis Theodorakis, known internationally for his earlier film score of Zorba the Greek (1964), was imprisoned and then exiled during the junta, but returned in 1974 when the country transitioned back to democracy. In 2012, the Greek parliament honored Lambrakis on the hundredth anniversary of his birth. Theodorakis continues to live and work in Greece.

This relatively optimistic song by Native American musician Periwinkle challenges everyone to recognize the role that they have to play in collectively preserving culture and building a better future. Her use of “us” (Indigenous people) and “them” (immigrant communities) near the end of the song morphs into an ultimatum when she suggests that “them” who don’t wish well for Native Americans in the United States might feel more at home living in countries abroad that have fascist or dictatorial regimes.

1. To read more about Woody Guthrie’s conceptualization of fascism, I recommend reading “Chapter 5” of John S. Partington’s The Life, Music and Thought of Woody Guthrie: A Critical Appraisal (2011).

2. Pete Seeger recalls how the performance context changed for this song from 1971 to 1978, before and after Franco’s death, on the 2003 release Spain in My Heart: Songs of the Spanish Civil War (Appleseed).

3. During the Spanish Civil War, Dolores Ibárruri galvanized the republican brigades to defend Madrid by declaring “They Shall Not Pass!” “No pasarán,” which echoes the message in “No nos moverán,” subsequently became the battle cry of the anti-fascist brigades.

4. To learn more about “No nos moverán,” I recommend reading David Spener’s We Shall Not Be Moved/No nos moverán: Biography of a Song of Struggle.