The Eclipse of the Sun 1926

Oil on canvas

207.3 x 182.6 cm

The Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntingdon, New York

George Grosz gave a fantastic testimony of Berlin life during a terrible period, divided between fascism and communism. He was active in the communist party but had an anarchist’s fascination for the characters of underground life. Military figures, prostitutes and violence abound, and fascinate the viewer.

George Grosz was an artist deeply rooted in his time. He gave a fantastic testimony of Berlin life during a terrible period in European history, reacting to the cultural and political problems of the day to produce a kind of art that was totally impregnated with the sense of a society in disruption – divided between fascism and communism. Although active in the communist party, he was much more of an anarchist than a communist; it was unthinkable for Grosz to be part of an organised, disciplined institution. As well as liberating him from the kind of dogmatism that destroyed so many artists in the 1920s and 1930s, this meant he instinctively rooted his art in the common people. It also explains, I think, why caricature and graphic design in magazines and newspapers held such an appeal for him.

Grosz shared Baudelaire’s romantic fascination for underground, outsider characters – criminals, gangsters, soldiers, suicide victims, the proletariat and whores. In that sense he was Germany’s poète maudit. A great example of this is his painting Suicide 1916. There is a prostitute standing by the window – a bottle in one hand. On one side a body is hanging from a lamppost, while another person, well-dressed, is lying on the street. (In his work, the theme of sex is always closely related to violence.) It has all the classic Grosz elements – dead people, prostitutes, perverted millionaires. All the characters have escaped the conformist respectable life. I think this is the reading that we should give to his gangsters, his killers – people who are outside the conventional social world. He thought, a bit like the Black Panthers 50 years later, that the criminals were the social fighters.

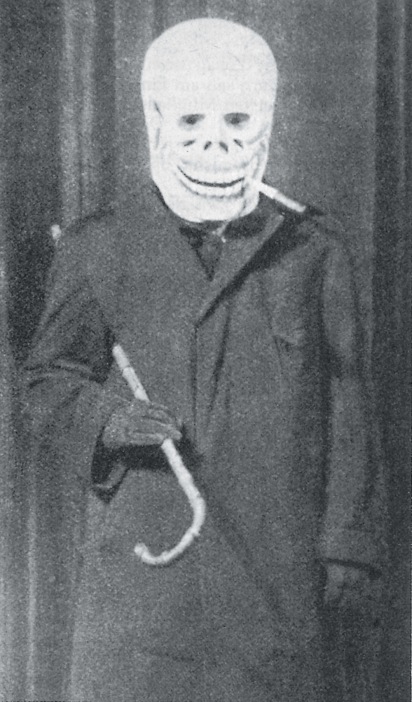

Where did this sensibility come from? The artist grew up in a time of death and destruction. The fragility of life was the air that he breathed. However, for him it was even worse. His father must have been rough, and perhaps brutal: in his autobiography Grosz mentions that he scared him and his sister Marta by showing them dancing skeletons in the garden. He died when the boy was seven years old. Grosz spent his childhood and adolescence in Stolp, a Prussian province, where his mother worked as a cook in the hussars’ barracks. He went to the local school until 1908, when, just before the end of his secondary studies, he was expelled for hitting a teacher. Among the hussars he doubtless learned to hate the Prussian officers, one of the main characters of the world that he immortalised in his work. The 1914–18 war had a traumatic effect on Grosz’s life and he soon ended up with what appeared to be a psychological breakdown. This accentuated the pessimistic and anarchic aspects of his personality and furnished him with many experiences that would help to shape the extreme, apocalyptic, dissolute nature of his artistic vision. But while he painted all this violence, we can see from his first drawings onwards that he had an ambivalent attitude towards it: he rejected it, and at the same time was fascinated by it. In this respect, he has had some influence on what I do. Grosz’s ambivalence is something that I have in myself. Violence is very present in my novels and essays. Most of my work is related to the kind of violence that is daily life in Latin America (though it was much worse in Grosz’s time; then it was vertiginous). My books are deeply critical of the sort of violence that is intimately related to dictatorships and military regimes. I reject all of this very strongly, but without it, my world would be incomprehensible. I reject brutality, but when I read Dostoevsky, or look at Grosz’s paintings, I find it fascinating. This is a great paradox of art and literature – what is despicable in life can be very attractive and appealing in art. You nourish yourself with everything that you hate. You can get a sense of this connection in one of my recent novels, The Feast of the Goat, a fiction modelled on the life of General Rafael Trujillo, the dictator of the Dominican Republic from 1930 until his assassination in 1961. Trujillo would have been a fantastic model for Grosz, and he would have been someone, I think, that he would have liked to have invented.

Some decades ago I spoke about “the purpose of being a writer is protest, contradiction and criticism”. I think that is still my impression. If you devote your life to trying to create a parallel world with words and with imagination, it is because the real world is not what you want; there is something lacking. So behind the act of inventing and creating another world, there is a deep rejection of the world as it is. It doesn’t mean that the reasons for rejecting it are always altruistic, or generous. It can be the reverse. Maybe you find the world intolerable because it is too good for your perverse instincts. But I think anticonformism is the basic drive behind a literary or artistic vocation. In my case this is quite conscious. I have, since I was very young, seen that writing was a kind of revenge; a way to express what is my criticism of life, of the world as it is. It is a revenge against Peru and Latin America, against brutality, against inequality, against dictatorships and corruption and against the kind of unjust society in which to be an artist, or to be a writer or poet, is an anomaly, because the conditions of society are such that literature and art, or culture in general, have a very marginal position.

Photo: © 2006 Estate of George Grosz/DACS, London 2007

When I started to write, there was still this idea that literature and art could be a very important tool to fight in historical terms, to improve the condition of victims in society. In this, Sartre was very influential with his idea of “committed” literature. This was very popular in Latin America at the time, though these ideas seem now a bit anachronistic.

I don’t think we can now believe, as we did in the 1950s, that what Sartre said – “words are acts” – is totally true. I don’t think the political or moral effect of an artwork or literary work is immediate and has visible consequences. On the other hand, I do not think that art or writing is something that produces pleasure without consequence. In the case of Brecht, who was more or less a contemporary of Grosz, he was so convinced that writing, producing and directing plays could bring about extraordinary changes in society. It has not happened as he thought. Now, as with Brecht’s plays, Grosz’s art has become much more appreciated for artistic and aesthetic reasons than for social or moral ones. But that doesn’t mean that there is no other effect than what we feel and experience when we see his work. For example, even though his caricatures are so schematic that they divide between good and evil, the sense of what is right and wrong is very instructive and enriching to me. So if you want to be a committed artist today, I think it is worth learning from the example of people such as Brecht and Grosz.