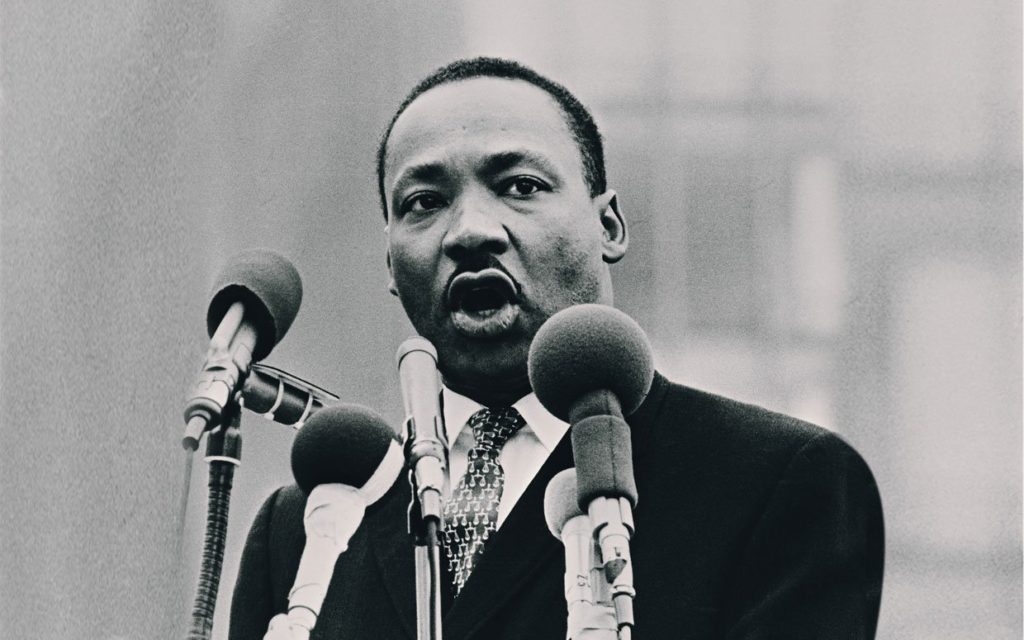

Katherine Weymouth–Photo Credit: The Daily Beast

If you had any doubt that the elite Washington press corps is too close to the political and corporate elites they are supposed to be scrutinizing, a recent scheme cooked up by the Washington Post might close the case.

The plan, as revealed by the website Politico (7/2/09), would have seen Post publisher Katharine Weymouth hosting a dozen off-the-record “salons” at her Washington home, bringing together lobbyists, politicians and some of the paper’s own reporters and editors. Each event would be “underwritten” to the tune of $25,000 by major players in select policy areas; the first scheduled salon, for example, was a discussion of healthcare policy (tentatively titled, “Healthcare Reform: Better or Worse for Americans?”) that was to be sponsored by healthcare giant Kaiser Permanente.

Forking over the money gave the underwriter a literal seat at the table—and, perhaps most important to the industry representative putting up the cash, a chance to “build crucial relationships with Washington Post news executives in a neutral and informal setting.” “Washington Post Salons are extensions of the Washington Post brand of journalistic inquiry into the issues,” draft marketing materials announced, “a unique opportunity for stakeholders to hear and be heard.”

The solicitation emphasized that the gatherings would be “bringing together those powerful few in business and policy-making who are forwarding, legislating and reporting on the issues,” and provide “an exclusive opportunity to participate in the health-care reform debate among the select few who will actually get it done.”

Where to start cataloging the ethical breaches here? Begin with the appearance of charging for access to the paper’s reporters, and the promise in the drafted marketing materials that the conversation would be “collegial” and non-confrontational. The fact that the solicitation assumes that government officials would be willing to participate in the Post’s commercial enterprise suggests an unhealthy coziness between press and state, particularly if you accept that politicians typically expect favors to be returned.

Soon after Politico’s report, the Washington Post canceled the planned event, claiming that it was the work of a rogue marketing department. It was, according to Weymouth, “never vetted by me or by the newsroom…. It completely misrepresented what we were trying to do.” Post executive editor Marcus Brauchli added that it was “absolutely impossible” that the Post newsroom would take part in such an event.

But an investigation by Post ombud Andrew Alexander (7/12/09) revealed an entirely different picture. In his recounting, based on internal emails and interviews with staff, the parameters of the events were known for months and were not radically different from the description in the marketing materials Politico had discovered. Top editors were aware, but did not raise a noticeable fuss over the events.

As Alexander wrote: “Several now say they didn’t speak up because they assumed top managers would eventually ensure that traditional ethics boundaries would not be breached. Neither Weymouth nor Brauchli can recall anyone raising concerns, although both say they wish someone had.” Well, that’s one form of journalistic ethics: waiting for someone else to object to something so obviously objectionable.

In fairness to the Post, there have long been similarly troubling arrangements at other outlets—like the L.A. Times’ decision in 1998 (Extra! Update, 8/98) to participate in an event sponsored by local PR agents that promised time “with key members of the Times’ editorial staff,” and a chance “to learn the latest media placement opportunities” in the business and magazine sections. The event even included a session titled “Breaking Down the Wall Between Business and Editorial at the L.A. Times.”

Off-the-record gatherings for elite political and corporate interests are lamentably common, though they aren’t usually so explicitly advertised as opportunities to spin the hosting news outlet; reporting in the wake of the Post story revealed similar arrangements at the Wall Street Journal and the Economist (Politico, 7/4/09). The Atlantic holds off-the-record sessions with journalists and political leaders (Washington Post, 4/27/09) and has also organized dozens of events underwritten by major corporations to discuss key issues in their industries—or, if you prefer, “private conversations among thought leaders,” as the magazine’s marketing materials put it (TPMMuckraker, 7/6/09). These include a Microsoft-sponsored discussion of global trade, and a talk on energy and nuclear power brought to you by General Electric.

The Atlantic also convenes corporate-friendly “public” events, and they’re not alone. Newsweek has held “executive forums” that “bring together policy experts and key figures in industry and the media for discussion and debate”—sponsored by, among others, Shell. These events are ostensibly open to the public (promoted in the magazines or on their websites), but the audience seems at best an afterthought.

As Harper’s Washington editor Ken Silverstein (7/14/09) pointed out, the website that embarrassed the Post doesn’t exactly have clean hands. Politico co-sponsored a party at the 2008 Democratic National Convention with D.C. lobbying powerhouse the Glover Park Group, and held an Oktoberfest party the previous year with the National Beer Wholesalers Association. Unseemly, to be sure—though one might feel the same way about “The Geopolitics of Energy Sustainability: A Thought Leadership Panel Discussion,” an event at the National Press Club (9/28/08) brought to us by Harper’s and Shell.

While the Post’s plan—and the L.A. Times’ a decade earlier—would seem to be more flagrantly unethical, none of the arrangements exactly inspire confidence in the idea of an independent and aggressive press. In the debate over the Post “salons,” distinctions are made between off-the-record and on-the-record sessions; gatherings where sponsors essentially shape the discussion raise more objections than when they have more of a backseat role. But it’s difficult for news consumers to find much reassurance in such hair-splitting.

The advantages for the moneyed interests at the table seem the same under all such arrangements: the chance to get a different sort of access to media or political figures than the unmoneyed could ever expect, and the chance to do so under the banner (quite literally, in many cases) of a news outlet whose journalistic reputation will lend prestige to corporate spin. That reputation can be cashed in with little upfront cost—though the long-term ethical write-down is harder to calculate.

News outlets trying to defend such practices sound like politicians who claim to be unaffected by the lobbyists and deep-pocketed contributors who bankroll their political careers. Such hollow claims of independence are dismissed by most observers of American politics. There is no reason to judge news outlets by a different standard.