The Turnbull government likes to call it an energy "trilemma" – how to meet the triple challenge of an affordable and reliable electricity system that also meets Australia's international obligations to cut emissions.

Its latest stab at the problem, though, is likely to fail on all three, not least because it treats the third leg of the stool as an optional extra.

More Federal Politics Videos

Tony's climate complex

Tony Abbott's speech in London "Daring to doubt" reveals how far the former PM needs to travel to find a receptive audience for his climate change denial. Artist: Matt Davidson

Multiple recent reports by regulators have highlighted the challenges facing the power sector, ranging from emerging risks of blackouts during the coming summer to a 63 per cent jump in electricity prices after inflation in the past decade, as identified by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission this week.

But it's been clear for months after the pushback from Malcolm Turnbull's Coalition MPs to the recommendations of a Clean Energy Target made by the Chief Scientist Alan Finkel in his major review, the first policy to go would be any serious commitment to Australia's Paris commitments to cut carbon.

As Turnbull told a media conference on Tuesday, the electricity generators – which produce a bit more than a third of total emissions – would be expected only to make a "pro-rata' contribution to pollution cuts.

Such a stance was flagged by Fairfax Media in June, when we noted the Finkel Review only modelled emission reductions by sector in line with Australia's promise to cut 2005-level national emissions 26-28 per cent by 2030.

That's despite virtually every other nation banking on its power industry to lead the way on emissions cuts.

The power industry has "the most obvious technological options" to reduce emissions, Erwin Jackson, a veteran of international climate talks now at Melbourne University's Australian-German Climate and Energy College.

"What you would be doing [by easing up on the electricity producers] is to force other sectors to do more and implement more expensive options to reduce emissions than is necessary," Jackson says.

(See International Energy Agency chart below modelling how emissions from the global energy sector, with rich nations expected to do more than the average reduction.)

Renewables outlook

Josh Frydenberg, whose twin ministry evolves more into an energy rather than an environmental one as each day passes, said renewable energy would supply 26-38 per cent of electricity by 2030. Some 18-24 per cent of that would be "intermittent" wind and solar.

Hugh Saddler, an honorary associate professor at the Australian National University, says business-as-usual policy would have delivered a share of about 39-40 per cent of the total by 2030, so any retreat would mean more emissions.

Further, if you assume AGL's ailing Liddell stays open – as the Turnbull government wants – and Canberra manages to nullify efforts by states such as Victoria and Queensland to set their own emissions goals, the share of renewables by 2030 would be as low as 32 per cent, Saddler estimates.

Next month's meeting of COAG energy ministers looks likely to be a heated affair if the states stand their ground. Energy investors, whose money is needed to invest in new plant to bring down costs and improve reliability, are also unlikely to be impressed.

Frydenberg concluded Tuesday's media conference by saying "other challenges" such as reducing emissions in agriculture and transport would need to wait to another day.

So far, though, only a pittance of funding has been set aside to promote more energy-efficient homes and buildings, and Australia has one of the weakest emissions standards of any developed nation.

And even if stricter rules were to apply, the slow turnover of vehicles – think roughly a decade – means emission cuts are well down the road. Don't even think about land-clearing emissions, which are likely soaring because of weakened restrictions in Queensland and now NSW.

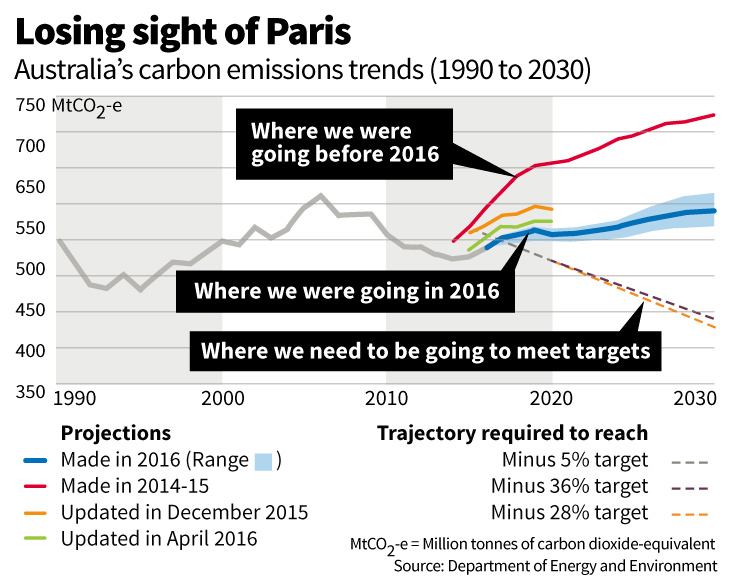

As its own environment department noted at the end of 2016, Australia's greenhouse gas emissions are trending higher, rather than the direction they should be headed.

At the end of last year, annual emissions were projected to reach about 592 million tonnes of carbon-dioxide equivalent by 2030, compared with about 550 million tonnes at the current level. (See chart below.)

That Paris is a fading chance is one thing, but how Australia is to hit a mid-century target of zero-net emissions along with other rich nations if we are to avoid dangerous climate change, becomes even less likely after the latest Turnbull effort to secure a political fix with his restless backbenchers rather than put the national interest first.

1 comment

New User? Sign up