Special mention

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 10 December 2017 in UncategorizedTags: rich, commons, cartoon, environment, middle-class, tax cuts, Trump, Mnuchin, national monuments

0

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 9 December 2017 in UncategorizedTags: banks, cartoon, CFPB, Mnuchin, rich, Wall Street, working-class

Capitalism and punishment

Posted: 8 December 2017 in UncategorizedTags: capitalism, crime, Dostoyevsky, homicides, inequality, novel

For years now, I’ve been writing about the various ways capitalism inflicts its punishments—including killing people (see, e.g., here, here, and here).

It’s as if capitalism is Dostoyevsky’s Rodion Raskolnikov, who formulates and executes a plan to kill a pawnbroker for her cash—and, in an attempt to defend his actions, argues that with the pawnbroker’s money he can perform good deeds to counterbalance the crime.

The question is, what are the good deeds capitalism performs to counterbalance its crimes? Because we now have more evidence that, like Raskolnikov, capitalism kills.

According to Maia Szalavitz, capitalist “inequality raises the stakes of fights for status among men.”

Obviously, potential murderers don’t check the local Gini Index – the most commonly used measure of inequality that looks at how wealth is distributed – before deciding whether to get a gun. But they are keenly attuned to their own level of status in society and whether it allows them to get what they need to live a decent life. If they can’t, while others visibly bask in luxury that seems both impossible to attain and unfairly won, those far from the top often become desperate.

And so, as capitalist inequality rises, men at the bottom are more inclined to kill other men—all in the name of honor and respect.

That conclusion is supported by a 2002 comparative cross-country study, published in the Journal of Law and Economics (pdf), whose main conclusion is that an increase in income inequality has a “significant and robust effect” of raising violent crime rates.

Perhaps those who defend capitalism think it possesses enough fortitude to deal with the ramifications of its crimes against humanity—that it even might have the right to perform those crimes. And the ability to get away with them.

Dostoyevsky, of course, suggested it’s better to confess and accept the appropriate punishment—which is exactly what Raskolnikov, at Sonya’s urging, finally does. But, alas, we don’t live in a nineteenth-century Russian novel.

In fact, in the United States, we are witnessing rising inequality and, for the first time in decades, rising homicide rates.

no one knows what time lag to expect between a rise in inequality and a rise in murder – but if it does take a few decades, this could be the start of a troubling trend, not a blip.

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 8 December 2017 in UncategorizedTags: cartoon, estate tax, GOP, middle-class, Republicans, tax cuts, trickledown, Trump, United States, Wall Street

How low can it go?

Posted: 7 December 2017 in UncategorizedTags: chart, class, Great Recession, inequality, labor, recovery, workers

The United States is now more than eight years out from the end of the Great Recession and the one-sided nature of the recovery is, or at least should be, clear for all to see.

Even as unemployment has dipped below the so-called “natural rate,” workers are far from recovering all they’ve last in the past decade.

According to the official data illustrated in the chart above, the labor share of national income remains just above the lowest level it reached in the entire postwar period. Using 100 in 2009 as the index value, the current labor share has fallen to 96.5—down from 110.24 in 2001 and 114 in 1960.

The question is, how low can the labor share go?

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 7 December 2017 in UncategorizedTags: cartoon, GOP, middle-class, Obama, poor, Republicans, rich, tax cuts, Trump, Wall Street

Whose recovery?

Posted: 6 December 2017 in UncategorizedTags: compensation, corporations, economy, productivity, recovery, regulations, tax cuts, Trump, unit labor costs, workers

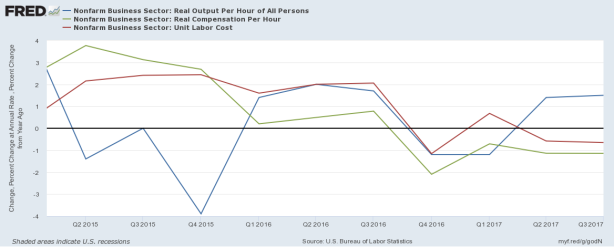

If you read the business press in the United States (e.g., the Wall Street Journal), you’ll find something along the lines of the following argument: the fact that U.S. worker productivity rebounded in the third quarter while hourly wages rose moderately is a sign “the economy is strengthening.”

But look at the numbers. Nonfarm business sector productivity (the blue line in the chart above) rose 1.5 percent (from the same quarter a year ago) while real hourly compensation (the green line) fell 1.1 percent.* The result is that unit labor costs (the red line) fell 0.7 percent.

According to Stephen Stanley of Amherst Pierpont Securities,

lighter regulation under the Trump administration and the prospect of a $1.4 trillion tax-cut package being passed by Congress are likely factors that have led companies to boost investment and become more productive.

Corporations may have chosen to boost investment and become more productive—but they have also chosen not to compensate their workers.

The only possible conclusion is that the Trump recovery is a recovery for employers but not for their employees.

Let’s see if Trump or someone in his administration will tweet that!

*Hours worked rose 1.5 percent and hourly compensation only 0.8 percent in the third quarter. As a result, real hourly compensation was -1.1 percent.