In a striking inability to gauge the mood of a good portion of its targeted audience, Verso Press distributed an announcement for this weekend’s “The Idea of Communism” conference with a couple of blurbs referencing its éminence grise and majordomo Slavoj Zizek as follows:

In a striking inability to gauge the mood of a good portion of its targeted audience, Verso Press distributed an announcement for this weekend’s “The Idea of Communism” conference with a couple of blurbs referencing its éminence grise and majordomo Slavoj Zizek as follows:

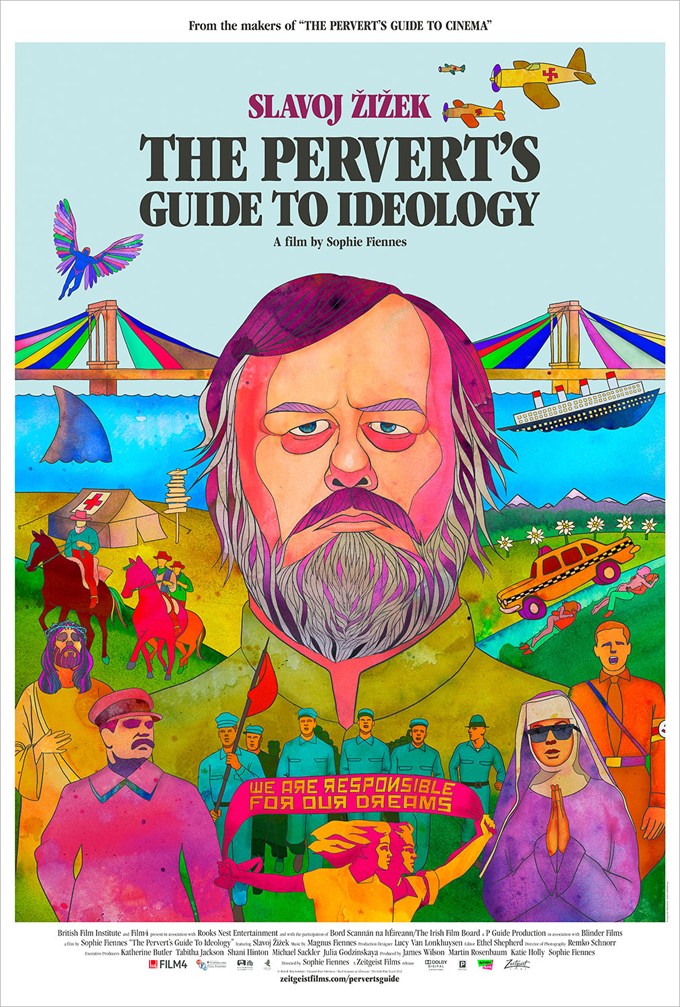

“Superstar messiah of the new left.” – OBSERVER

“Slavoj Zizek is a superstar of Elvis-like magnitude–a bogglingly dynamic whirlwind of brainpower.” – DAZED AND CONFUSED

Superstar… Elvis-like… Messiah…

No wonder so many people bought into the hoax that Zizek and Lady Ga Ga were intellectual soul mates.

To some extent this obsession with celebrity is understandable because the powers that be at Verso Press and New Left Review must see themselves in the same terms. Whether this has anything to do with the proletarian orientation of the movement that Marx founded is of course another story altogether. How odd that the goal of some “revolutionaries” today is a guest appearance on the Charlie Rose show or a profile in Vanity Fair.

While I was put off by the publicity, I felt I owed it to myself and my readers to take advantage of Verso’s live streaming of the event. I have become more and more aware of a kind of trend emerging around Zizek, Jodi Dean and Alan Badiou that is distinguished by its insistence on using the term communism as well as its admiration for Lenin. It is a barometer of opinion in the academy that “communism” and Lenin can be placed in the center of a professor’s escutcheon (likely after attaining the safety of tenure.)

While Zizek refers to himself frequently as a “die-hard” Leninist, there is some question whether he understands the fundamental basis of Lenin’s politics, namely class independence. In a October 29, 2009 interview with Jonathan Derbyshire in the New Statesman Zizek said:

I am a Leninist. Lenin wasn’t afraid to dirty his hands. If you can get power, grab it. Do whatever is possible. This is why I support Obama. I think the battle he is fighting now over healthcare is extremely important, because it concerns the very core of the ruling ideology. The core of the campaign against Obama is freedom of choice. And the lesson, if he wins, is that freedom of choice is certainly something beautiful, but that it only works against a background of regulations, ethical presuppositions, economic conditions and so on. My position isn’t that we should sit down and wait for some big revolution to come. We have to engage wherever we can. If Obama wins his battle over healthcare, if some kind of blow can be struck against the ideology of freedom of choice, it will have been a victory worth fighting for.

While many are the charlatans who spoke in the name of Karl Marx, starting with Eduard Bernstein, Zizek has the distinction of saying the most anti-Leninist things in the name of Lenin, it would appear.

Unlike Zizek, whose “Leninism” is of recent vintage, Badiou is a soixante-huit Maoist. While Badiou’s fellow Maoists (André Glucksmann, Bernard-Henri Lévy et al) became turncoats, he remains true to his youthful beliefs. That, plus the fact that the Kasama Project speaks highly of him, gives him a certain legitimacy. That being said, Badiou seems to share the prevalent philosophical idealism of his fellow conferees (illness prevented Badiou from making an appearance).

Zizek, Dean, Badiou are clearly in the tradition of what Perry Anderson diagnosed in his 1976 “Considerations of Western Marxism”. Back in 1992 or so, when I was first exposed to the academic left on the Internet, I was so perplexed by all of the philosophical mumbo-jumbo that I found myself searching for an explanation of where it came from. I had given up my pursuit of a philosophy PhD in 1967 to join the Trotskyist movement and could not fathom why so many Marxist intellectuals were touting exactly the thinkers who I had abandoned 25 years earlier: Spinoza, Kant, Hegel, Heidegger et al. As Marx had put it, the point was to change it. Right?

Anderson, no matter his confusion over so many things nowadays, had a pretty good explanation:

Western Marxism as a whole thus paradoxically inverted the trajectory of Marx’s own development itself. Where the founder of historical materialism moved progressively from philosophy to politics and then economics, as the central terrain of his thought, the successors of the tradition that emerged after 1920 increasingly turned back from economics and politics to philosophy – abandoning direct engagement with what had been the great concerns of the mature Marx, nearly as completely as he had abandoned direct pursuit of the discursive issues of his youth. The wheel, in this sense, appeared to have turned full circle. In fact, of course, no simple reversion occurred, or could occur. Marx’s own philosophical enterprise had been primarily to settle accounts with Hegel and his major heirs and critics in Germany, especially Feuerbach. The theoretical object of his thought was essentially the Hegelian system. For Western Marxism by contrast – despite a prominent revival of Hegelian studies within it – the main theoretical object became Marx’s own thought itself. Discussion of this did not, of course, ever confine itself to the early philosophical writings alone. The massive presence of Marx’s economic and political works precluded this. But the whole range of Marx’s oeuvre was typically treated as the source material from which philosophical analysis would extract the epistemological principles for a systematic use of Marxism to interpret (and transform) the world – principles never explicitly or fully set out by Marx himself. No philosopher within the Western Marxist tradition ever claimed that the main or ultimate aim of historical materialism was a theory of knowledge. But the common assumption of virtually all was that the preliminary task of theoretical research within Marxism was to disengage the rules of social enquiry discovered by Marx, yet buried within the topical particularity of his work, and if necessary to complete them. The result was that a remarkable amount of the output of Western Marxism became a prolonged and intricate Discourse on Method. The primacy accorded to this endeavour was foreign to Marx, in any phase of his development.

For Anderson, the key to understanding the “philosophical” turn was the series of defeats in the 1920s and 30s that left many intellectuals in despair. If Stalinist and imperialist hegemony militated against the revolutionary project, then the next best thing might be an academic career where a kind of watered-down Marxism might be tapped for interesting lectures on Alfred Hitchcock movies and the like for audiences at conferences in places like London or Paris, with travel and hotel paid by one’s employer. That would be much more profitable than writing analyses of the capitalist economy in order to help develop strategy and tactics for the workers movement. That might have been how Lenin became a celebrity of sorts in Czarist Russia but that route was excluded for the modern and chastened left academy. Plus, Alfred Hitchcock movies were a lot more fun than pouring over land tenure or labor demographics.

Household chores and other research projects prevented me from watching the entire conference, but I did manage to check out the Saturday morning talks by Bruno Bosteels and Susan Buck-Morss, and Sunday’s with Jodi Dean and Zizek. The brunt of my comments will be directed at Dean and Zizek, but I do want to say a few brief words about Bosteels and Buck-Morss.

Bosteels’s talk was a mild polemic directed against Zizek’s attempt to reconcile Marxism and Christianity, the subject of his 2001 “The Fragile Absolute: Or, Why is the Christian Legacy Worth Fighting For?” Bosteel’s talk first appeared as an article titled “Are There Any Saints Left? León Rozitchner as a Reader of Saint Augustine” in the 2008 Polygraph (19/20). It is essentially an indictment of St. Augustine as a precursor to modern day imperialism, a rather uncontroversial thesis given the fact that his “City of God” was essentially a defense of the Holy Roman Empire. As my senior thesis at Bard College was a study of this book, I confess to having no inkling of its sinister motives at the time. I was a big fan of St. Augustine’s Confessions that resonated with my own adolescent angst and assumed that “The City of God” would be more of the same.

At the time (1965), I never once considered that a book might serve reactionary aims. My only problem with Bosteels’s approach to this classic is that it can easily be interpreted as idealistic. In other words, St. Augustine’s bad ideas explain the horrors of the Crusades, etc. At the risk of sounding hopelessly old-fashioned, I would look at the Crusades as driven more by a need to challenge Muslim commercial interests and to open up trade routes, but that’s just me and my moldy fig Marxism.

The first half of Susan Buck-Morss’s talk on communism and ethics was largely incomprehensible, dwelling on ontology and other matters related more to philosophy than political economy. The second half was what Teresa Ebert once called a “postal” attack on Marxism, including the usual complaints that it prioritizes a working class that no longer exists, instructs women and Blacks to wait until capitalism is overthrown for its problems to be solved—in other words, a mindless caricature.

Buck-Morss is an Adorno expert and as such found herself in the good graces of the Platypus Society that is striving after a synthesis of the Spartacist League and the Frankfurt School. In an April 2011 interview with the group, Buck-Morss told the boys what was wrong with people like Che Guevara and Ho Chi Minh:

The whole discourse of “the enemy” or “the class enemy” in the Old Left was about putting people against the wall and shooting. I do not consider it progressive anymore, if it ever was, to justify violent insurrection on the basis that the state was not going to fall on its own.

Her grasp of economics is as sure-footed as her grasp of the nature of the state. The next morning she took the mike after Jodi Dean’s talk and relayed her concerns about the OWS 1/99 percent distinction that did not address the fact that many people in the United States were “capitalistic” because of their mortgages and their 401-k’s. When I used to sell the Militant newspaper door-to-door in the Columbia University dormitories in 1969, I used to hear the same argument. Little did I expect to hear it from a relatively famous almost-Marxist professor.

Google “Jodi Dean” and “Communist Desire” and you’ll be able to read the talk she gave this morning. It is a kind of psychoanalysis of the left:

If this left is rightly described as melancholic, and I agree with Brown that it is, then its melancholia derives from the real existing compromises and betrayals inextricable from its history, its accommodations with reality, whether of nationalist war, capitalist encirclement , or so-called market demands. Lacan teaches that, like Kant’s categorical imperative, super-ego refuses to accept reality as an explanation for failure. Impossible is no excuse—desire is always impossible to satisfy.

My take on this is somewhat different than Professor Dean’s. My RX for combatting melancholia is victories, no matter how minor, against the bourgeoisie. To achieve such victories, it will require strategy and tactics that Malcolm X once described as “designed to get meaningful immediate results”. Such actions are surely aided by a solid analysis of the relationship of class forces that can only be derived by a study of bourgeois society such as the kind found in classical Marxism and not Frankfurt-inspired philosophizing, I am afraid.

Zizek’s talk was a bad boy exercise in epater la bourgeoisie that he is famous for. He scoffed at the priority that the left had put on winning democracy and urged the need for violence, calling attention to how demonstrators in London had broken windows earlier in the year. Without breaking the windows, nobody would have noticed. Fortunately, the mass movement no longer pays attention to such provocative suggestions.

Dean unfortunately has bought into Zizek’s bad boy routine and even defended it against his critics. Google “Jodi Dean” and “Zizek Against Democracy” and you will be able to read a document that states:

Some theorists construe Zizek as an intellectual bad boy trying to out-radicalize those he dismisses as deconstructionists, multiculturalists, Spinozans, and Leftist scoundrels and dwarves. Ernesto Laclau, in the dialogue with Zizek and Judith Butler, refers scornfully to the “naïve self-complacence” of one of Zizek’s “r-r-revolutionary” passages: “Zizek had told us that he wanted to overthrow capitalism; now we are served notice that he also wants to do away with liberal democratic regimes.” Although Laclau implies that Zizek’s anti-democratic stance is something new, a skepticism toward democracy has actually long been a crucial component of Zizek’s project. It is not, therefore, simply a radical gesture.

Indeed, part of Zizek’s talk this morning dealt with exactly this question, scoffing at those leftists who care about which judge will be elected. He reminded the audience that Marx believed that it was only through seizing state power and abolishing capitalist property relations that true freedom could be achieved. That of course would be news to Marx scholars like August Nimtz, whose “Marx and Engels: their contribution to the democratic breakthrough” revealed their commitment to what Zizek writes off. The book includes this epigraph that obviously Zizek would regard as liberal mush:

The movement of the proletarians has developed itself with such astonishing rapidity, that in another year or two we shall be able to muster a glorious array of working Democrats and Communists — for in this country Democracy and Communism are, as far as the working classes are concerned, quite synonymous.

–Frederick Engels, “The Late Butchery at Leipzig.-The German Working Men’s Movement”

And as far as the “ruthless” Lenin, scourge of democratic half-measures, was concerned, this was his assessment in “What is to be Done” of what the Russian socialists (he used this term much more frequently than communist) had to do to live up to the standards of the German social democracy, a party he was seeking to emulate:

Why is there not a single political event in Germany that does not add to the authority and prestige of the Social-Democracy? Because Social-Democracy is always found to be in advance of all the others in furnishing the most revolutionary appraisal of every given event and in championing every protest against tyranny…It intervenes in every sphere and in every question of social and political life; in the matter of Wilhelm’s refusal to endorse a bourgeois progressive as city mayor (our Economists have not managed to educate the Germans to the understanding that such an act is, in fact, a compromise with liberalism!); in the matter of the law against ‘obscene’ publications and pictures; in the matter of governmental influence on the election of professors, etc., etc.

That’s the Lenin we must learn from, not Zizek’s cartoon-like figure who comes out of a 1950s Red Scare B-movie.

In a striking inability to gauge the mood of a good portion of its targeted audience, Verso Press distributed an announcement for this weekend’s “The Idea of Communism” conference with a couple of blurbs referencing its éminence grise and majordomo Slavoj Zizek as follows:

In a striking inability to gauge the mood of a good portion of its targeted audience, Verso Press distributed an announcement for this weekend’s “The Idea of Communism” conference with a couple of blurbs referencing its éminence grise and majordomo Slavoj Zizek as follows: