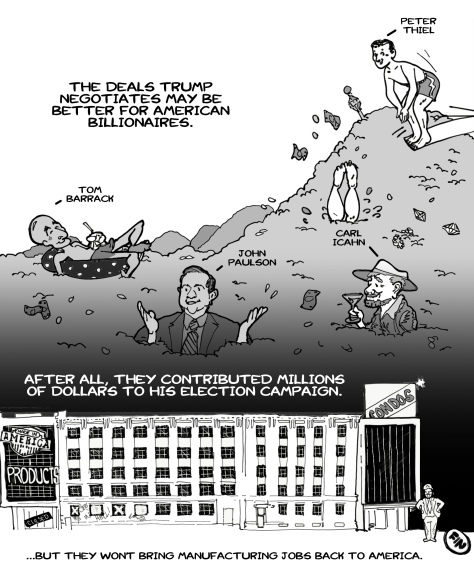

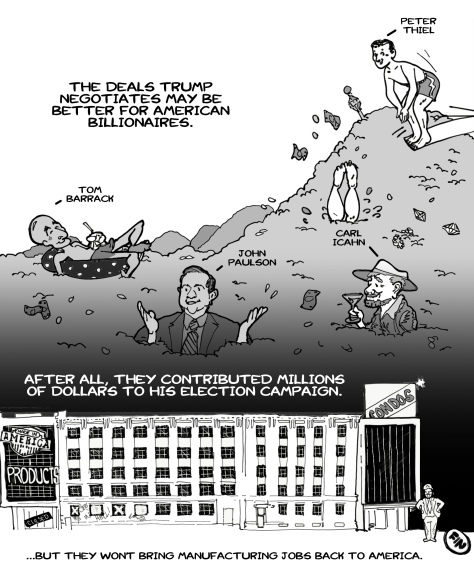

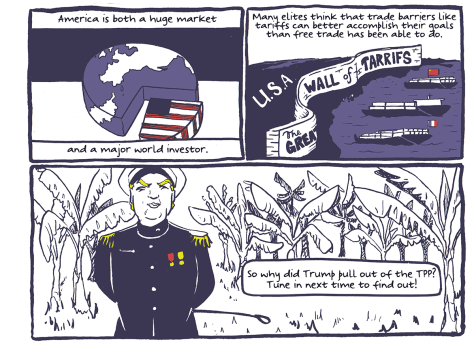

The Left was baffled in 2016 to learn that Trump was taking a stance against the Trans-Pacific Partnership, or TPP. As the new administration fires up for trade wars, perhaps it’s time to review what we know about the role of the American state in international trade.

I’m on tour at the moment and am moving like molasses, but I’ve finally gathered myself up from drawing my own comic that takes place in Alberta, to talk about my *favourite* comic that takes place in Alberta. Michael Comeau’s ‘Hellberta’ has been described elsewhere on the internet as “one of the most meaningful and interesting” variations of a Wolverine comic, and I must agree. It explores the Canadian home of one of comic fandom’s most celebrated characters, against a background that is at once both more realistic and more surreal than your garden-variety Marvel title.

My conversation with Michael is below. For a better run-down on the plot and cultural significance of ‘Hellberta’, I recommend reading the Barbed Comics review linked above. To pick up a copy for yourself, you can do so here.

N: What was your relationship to comics growing up? To X-men and Wolverine in particular?

M: I collected the “Uncanny X-men” from the Mutant Massacre story arc to when Jim Lee branch off to the merely “X-men” title approximately 1986 to 1991. Wolverine emerged as an intriguing character for me and many others. The Chris Claremont, Frank Miller mini series is the quintessential statement on the character. I bought an old “Inferno” issue of Uncanny X-men in Drumheller Alberta and began drawing Wolverine. I didn’t pay attention to super hero comics for around a decade and was mildly annoyed to find out they filled out Wolverine’s back story to be that his name was no longer Logan but James Howlet and he was originally British. I can usually recognize when a writer can’t grasp the Canadian hoser Logan archetype so it poses the question what would I do with the character. The reclamation of Wolverine opened up notions of Canadian identity like collaging the archetypes of Neil Young and Logan.

I often find myself fantasizing about the ability of the supernatural (and by extension, superheroes) solving the world’s social and political problems, beyond what I would see in your standard comic book. So I’ve found that Hellberta has been really satisfying for me and other activist folks I’ve shown it to. Would you describe Hellberta as a kind of political revenge porn, like Inglorious Bestards is to nazism or Django Unchained to slavery and racism?

I am a straight/cis/white man from Ontario who learned about Albertan activist culture among the oil sands boom while living and traveling with queer and trans people from Calgary. I was unsure how to depict the queer flight from Calgary or the environmental impact of the tar sands so I took a popular myth from the area and supplanted it onto the situation. What would Wolverine do? Superheroes are extensions and exaggerations of our hopes and fears I don’t really see them as rising above anything. I’d rather see them struggle with our same mundane problems in spite them being so exceptional.

I would hate it if someone compared anything I’d done to a Tarantino film, so in your own words – what were you going for with Hellberta? What would you say were your influences or sources of inspiration?

A: Initially it was a cahier de voyage with rough drawings that were somewhat related to our adventures on the road. Then I included the Wolverine vs. the tar sands as a way to learn how to make a comic. It had direct X-men references like how Wolverine would “hunt” deer by creeping up and touching them or the Phoenix as an arbitrary global catastrophe and an Osamu Tezuka style time lapse of total destruction to gradual renewal. The photo comic section was based on the relationships Logan has with young women. He is a good archetype for intergenerational friendships with women. The “Sackville Slapper” section is more about trajectories across provinces. It is inspired by Donald Shebib’s “Going Down The Road” movie and the SCTV spoof of it. Both of my parents are from New Brunswick and i wanted to reference the east coast. The idea was Logan as Popeye and Puck as Wimpy in an east coast Tijuana Bibles style book which is a paradigm shift away from the photo comic.

There’s a lot of Christian iconography in this book that can’t go unnoticed. Harper and his harlots fly around on a cross, but it is Wolverine who is martyred and rises again. How did you decide to incorporate this imagery?

Christianity is a conquering ideology used in colonization. It severs a localized spiritual connection to the land. I often think of what therapists call the “reversal of desire” regarding someone feeling repressed and ostracized by images of Christ and finding comfort in Satan etc. Like a metalhead teenager. In processing my own catholic repression I enjoyed drawing from medieval christian imagery. Wolverine is a classic christ figure. Sacrificing himself to be resurrected through his homo-superiority ie. healing factor. He regularly gets crucified onto X’s in comics. The Right Wing wields notions of God as a weapon and I wanted to counter that with what is essentially the same human impulse to create heroes/gods but from a far more transparent place as pop culture.

One question for the printing nerds: take us through the printing process of this book, because the dual tone is enough to make your brain want to explode. It kind of feels like a throw-back to those cheap 3D graphics with the red & blue ink that you could dig out of the bottom of a cereal box. How did you decide on this technique?

I’ve created and printed many 2 colour screen printed posters. The first issue was printed on Jesjit Gill of Colour Code Printing’s very first risograph machine which only printed one colour at a time so the registration had to be very loose. I was doing the dot tone with a photocopier. Copying over top the lines or turning the breakdown into a negative, copying over a negative dot tone and reversing back to positive and then copy over top the line work. I am fascinated by the timbre of an image and use of tone. It is constantly evolving through out my work.

Do you see yourself making anything in this vein again?

There is an Alpha Flight story in my head that has haunted me for years. I have done my own riff on Son of Satan but now for the most part I am working on original stories with only some sketchbook strips that might be bootleg. Lately when I don’t know what to draw I do without reference Superman, Wonder Woman and Batman. No matter how crud the drawing is you still project the characters onto them. So naturally I have thought of dumb, petty dialogue for them to exchange.

Since this comic was created, pipeline projects (and their messes) continue to dot the North American landscape.We’re also entering a “Trump era”, which shares a fair bit of common ground with the Harper Government. Do you think Wolverine is an important hero to have in an age like this?

Heroes are as important as we make them. Each situation is gazed at through the lens of the hero prism. Be it Wolverine, Jesus, Tupac or Joni Mitchell. Logan is post-human, a homo-superior, so he points to the future but is from the far past.

In January 2017, Ad Astra Comix is teaming up with Toronto-based artist and activist Tings Chak to produce a new and improved 2nd edition of their work, “UNDOCUMENTED: The Architecture of Migrant Detention”.

This 120 page book of illustrations, diagrams, and comics journalism-style interviews with former detainees explores the world of migrant detention from the intersection of architecture and migrant justice. The result is a unique and eye-opening argument for an end to migrant detention as we know it –or, in many cases, as we have only begun to discover it exists.

Pre-orders for the book’s 2nd edition will begin with a crowdfunder in January, and we’d like to use the crowdfunder as an opportunity to celebrate all art against migrant detention.

– End Migrant Detention

– Refugees Welcome Here

– No One Is Illegal

– Stop the Deportations

– Migration is Not a Crime

If you are an artist and would like to “donate” a digital file as a promotional perk, we will promote your art through the crowdfunder and compensate you for your work to the tune of a 20% royalty on all items sold. Please e-mail adastracomix@gmail.com for details.

Deadline for art submissions will be January 1, 2017. We request that files be 300 dpi, black and white or colour, and between the size dimensions of 5″ x 7″ – 18″ x 24″ (irregular dimensions may also be accepted). Any questions or concerns, please e-mail Ad Astra Comix at adastracomix@gmail.com.

Check out some beautiful migrant justice artwork through the JustSeeds print collective and their collection, “Migration Now!” Have any other inspiring suggestions? Msg us and we’ll share it!

Ad Astra Comix is pleased to announce the second edition of ‘Undocumented: The Architecture of Migrant Detention“. First published by an academic architecture publisher in 2014 in a limited run, we are excited to bring ‘Undocumented’ to a wider audience.

As with previous Ad Astra projects, a pre-order campaign will be held to raise awareness and cover the costs of printing. Stay tuned for details!

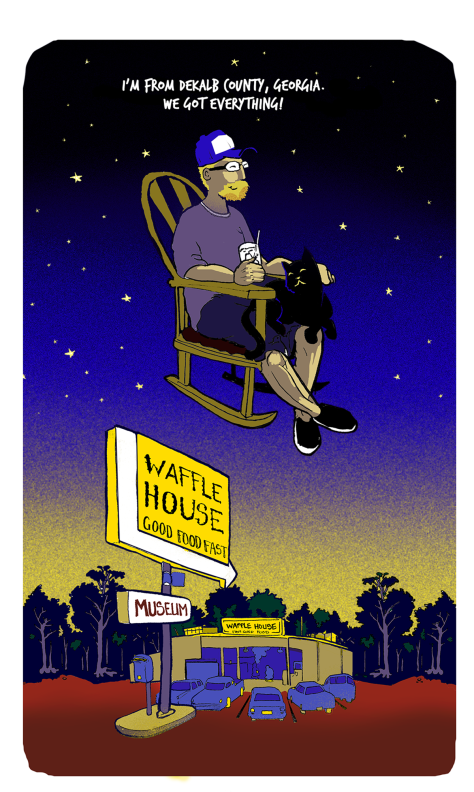

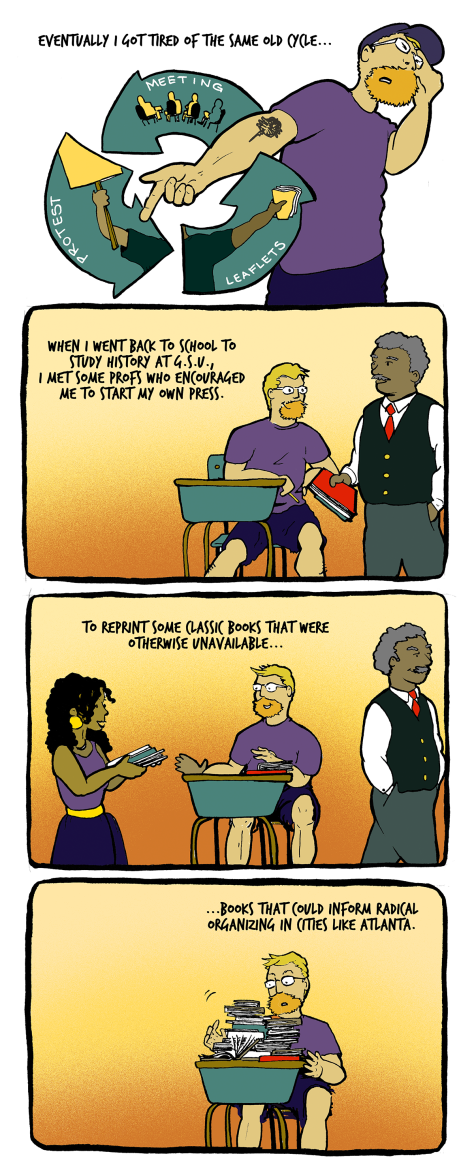

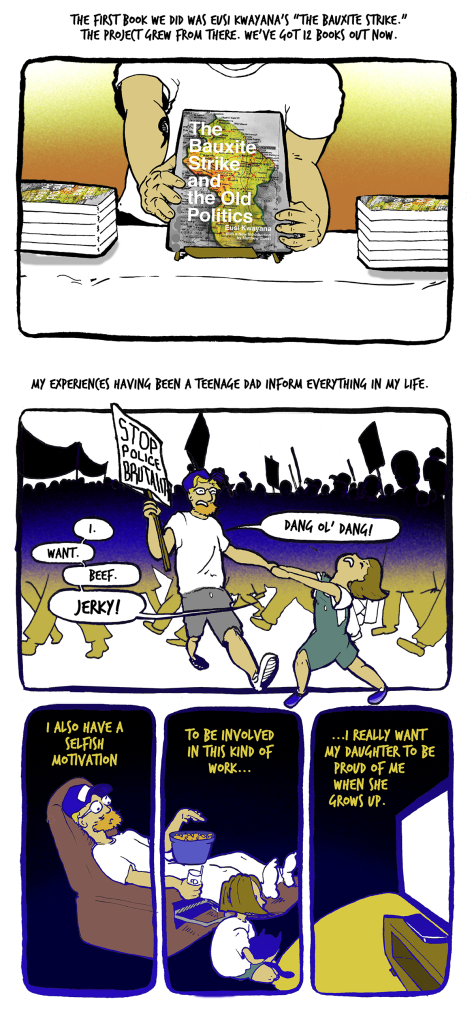

Last January, we spent time in Atlanta Georgia with our friend. Specifically, we spent time in Dekalb County, Georgia, with Andrew, the co-founder of On Our Own Authority Books and his daughter, Olivia. This comic is about them.

Anyone who has accidentally gotten their one theatre friend talking has heard of ‘RENT’, the 1993 musical about artists and activists living in Alphabet City, New York. But far fewer people have ever heard of Seth Tobocman’s ‘War in the Neighborhood’, a graphic novel published in 1999 that has more than a few similarities to ‘RENT’. How many? Let’s take a look.

1. Both take place in New York City’s Lower East Side

1. Both take place in New York City’s Lower East SideSure, Alphabet City is a little bit more specific than ‘Lower East Side’, but it’s the same neighborhood, a stretch of blocks between Avenue 1 and A Street. Now one of the most expensive places to live in North America, the Lower East Side once had a reputation for being a haven to bohemians, radicals, immigrants and anyone else looking for a cheap place to live as they set out to build lives in the capital of the world. The perfect place to write a tragedy in the case of ‘RENT’, or watch one unfold, in the case of ‘War in the Neighborhood’.

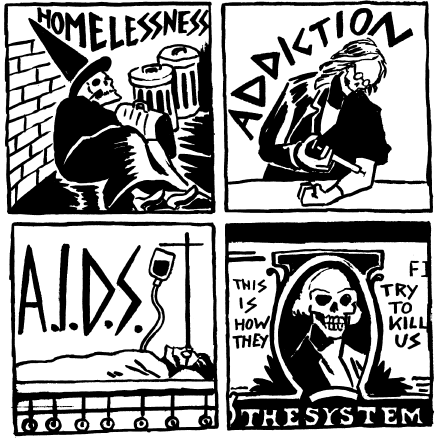

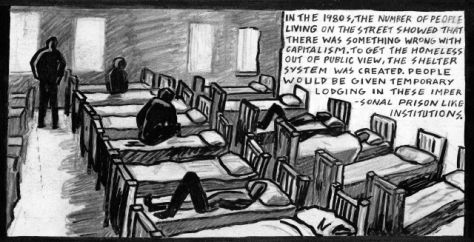

No, not that Bush. From 1988-1992, George Bush Sr. was president of an America in transition. Eight years of Ronald Reagan had kick-started the “War on Drugs”, broken the back of the labor movement and set the stage for the disappearance of the middle class. Many of the themes the two works have in common: the AIDS crisis, gentrification, conscientious objection to said “War on Drugs,” and heavily politicized art. Romantic as life on the Lower East Side might seem in art, the lived reality was often one of hunger, cold and constant anxiety that today would be eviction day. Both ‘RENT’ and ‘War in the Neighborhood’ show that heady mix of insecurity and adventure.

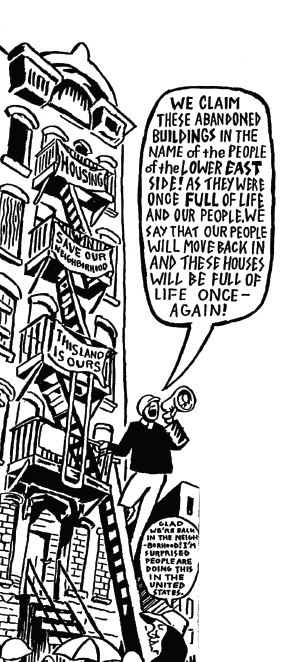

At the root of that anxiety about displacement, of course, was gentrification. After decades of neglect and urban decay, developers in New York City saw an opportunity. Slowly, condos began springing up along with yuppie shops, gyms and coffee bars, pricing residents out of their own communities.

Both the squatters and gentrifiers look at the decaying urban infrastructure and see possibility: but where squatters see the potential for an inclusive, self-reliant community, gentrifiers saw an opportunity to turn a profit regardless of the human cost.

In ‘RENT’, Benny is an affable tech entrepreneur who promises his old bohemian buddies a home in his state-of-the art “cyber studio” – but only if they can stop a protest happening in the neighborhood—against what? Gentrification. Meanwhile, this process of urban transformation is illustrated as a gigantic serpent in ‘War in the Neighborhood’, coiling itself up the old apartment blocks and suffocating the life out of the people who live there. Backed by the power of local politicians, this force seemed unstoppable.

In both stories it is a group of squatters who form a front-line opposition to this community takeover. They occupy the abandoned buildings before the landlords get a chance to burn them down. While Roger and Mark may be living for free, courtesy of Benny, Mimi and the rest of the squatters seen in ‘RENT’ are very much taking their chances. Squatting is a major theme of ‘War in the Neighbourhood’, where the struggle to build a life that you could lose at any time appears again and again.

Sure enough, wherever there are struggles against gentrification, anarchists probably aren’t far behind. In ‘War in the Neighborhood’, anarchists party in Tompkins Square Park, fight the police, denounce Leninists, and insist on democratic process in the governance of the squats. As for ‘RENT’, Although almost the entire cast exudes a cheeky anti-authoritarianism, only former professor Collins is explicitly identified:

‘And Collins will recount his exploits as an anarchist – including the tale of the successful reprogramming of the M.I.T. virtual reality equipment to self-destruct, as it broadcasts the words: “Actual reality – ACT UP – Fight AIDS!”

The Bush years marked a continuation of Ronald Reagan’s so-called “War on Drugs”, an effort that led to moral panic, militarization of police forces, and the criminalization of people living with addiction. In Rent, Roger is recovering from a heroin addiction, while Mimi is actively using. The question of addiction is portrayed sentimentally and feels a little bit borrowed for the sake of deepening tragedy. In ‘War in the Neighborhood’, several characters are addicted to heroin, cocaine, or crack, and there is nothing romantic about it. Tobocman portrays drug use as a fact of life under capitalism—the baggage that we sometimes carry with us to deal with our pain. The question of whether or not to let people use drugs in the squat is a major source of conflict: how do we build a new world that is inclusive and supportive when we carry so much baggage from the world we want to leave behind?

It’s impossible to write about New York City in the Bush Sr. years without addressing the AIDS crisis. Government silence and inaction allowed the disease to become an epidemic, devastating affected communities. In RENT, fully half of the main cast has AIDS, which claims the life of Angel, a drag queen and street performer. In the middle of ‘La Vie Boheme’, the cast leans on the fourth wall by referencing ACT UP, the direct action group organized by people living with AIDS.

ACT UP also appears in ‘War in the Neighborhood, where Scarlett is a squatter living with the virus, struggling to find a safe space in the middle of a virtual war zone. They struggle to find the physical energy, let alone the spirit, to continue the fight for housing. Another character, Tito, is bedridden due to complications but is able to keep watch for nearby squatters and help them stay safe.

Anyone walking through the Lower East Side can see that gentrification has won. The bohemian utopia, always half-imaginary, exists only in works like Rent and ‘War in the Neighborhood’. It isn’t easy to tell the story of its life without touching on the death that was all around.

In ‘RENT’, the death of Mimi is the most visible impact of the AIDS epidemic, though people disappear steadily from her AIDS support group. Tension around Angel’s death fragments their circle of friends. In ‘War in the Neighborhood’, the squats slowly dissolve in a mix of death, eviction and interpersonal conflict.

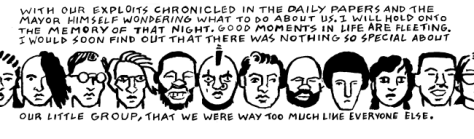

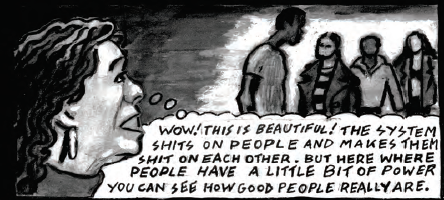

But neither one ends as a tragedy. Rent ends with Mimi pulling back from the brink of death, following Roger’s confession of love. ‘War in the Neighborhood’ ends with a thoughtful meditation on how hard we are on each other, and that if we can see the possibilities in what we might be, there’s no telling what we can do.

Maybe good tragedies need a moral lesson to soften the blow. I think both these stories end with a moral: ‘keep living; there is hope’. And hope, these days, is in short supply. We’ve got to take it where we can find it; to make the most of the time we have.

We’re publishing a second edition of ‘War in the Neighborhood’! To order your copy, check out our crowdfunder or, head over to our press kit to learn more about the book.

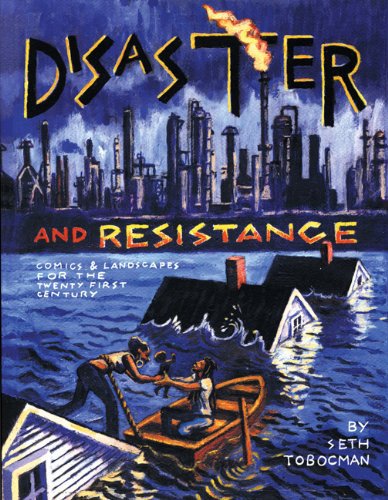

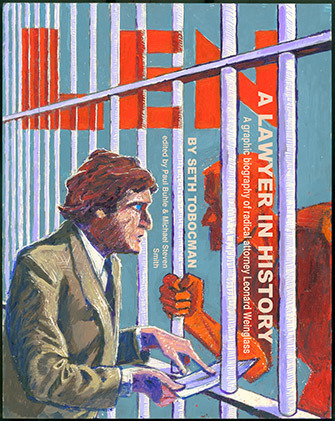

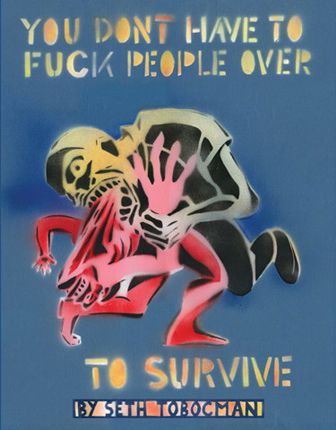

Other books that Seth has contributed to:

Since 1979, Seth has contributed art, money, and time to the radical comics anthology, World War 3 Illustrated. Here are a few…

The struggles we find ourselves in –for justice, equality, and a democracy worthy of the name– are not new. Yet we’re endlessly forming new groups, writing new charters, experimenting with new tactics as though we were the first people ever to struggle against injustice.

The struggles we find ourselves in –for justice, equality, and a democracy worthy of the name– are not new. Yet we’re endlessly forming new groups, writing new charters, experimenting with new tactics as though we were the first people ever to struggle against injustice.

Driving across North America in the past year, we were struck by the profound lack of institutional memory in radical communities wherever we went. People doing work that was important, even essential, could often tell us nothing about what their organization had been like 10 years ago, if it had existed at all.

The left leaves few records and most of these are hagiographies–saintly accounts of the lives of larger-than-life heroic figures that read more like myths than histories. It is a rare book that transcends this shallow style and speaks frankly about the painful difficulties encountered by social movements. That kind of book is full of important lessons for us. ”War in the Neighborhood’ is that kind of book.

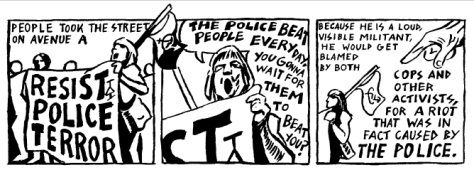

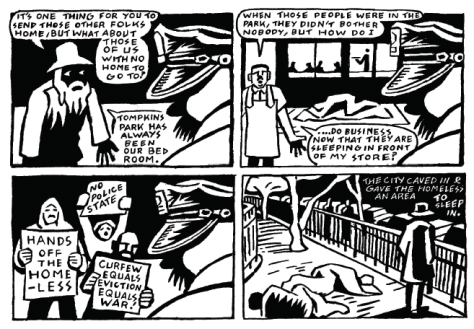

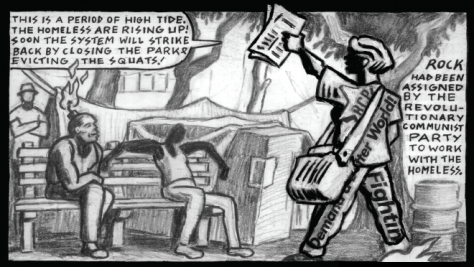

‘War in the Neighborhood’ is partially about the struggle to protect the public’s right to use Tompkins Square Park. One of those uses, dating to before the struggle, is as the site of a tent city for the homeless. In the course of the struggle to preserve the park as a place to drink and hang out, conflicts with the cops made it an unsafe place to sleep.

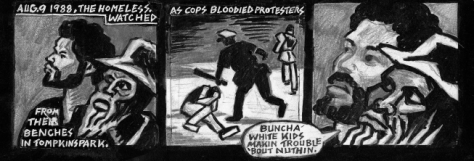

Confrontations between cops and activists would raise the emotional temperature of the park, but while the activists could go home, many of the people living in the tent city were home – and had nowhere to go when the cops came to work out their frustrations.

“Reclaiming” urban space is always more complicated than it looks. In North America particularly, that space is always colonized land. In a more immediate sense, the space is often being used by people who don’t want to see it ‘reclaimed’. During the era of the Occupy camps, we dropped into that park without any notion of this. We were bringing media and police attention to a space that homeless people had been living in quietly for years.

I wish we’d all known a little bit more about past struggles like ours, and known ahead of time that we needed to be mindful of the needs of the folks already living in the park. They are capable of doing their own very powerful organizing if they choose, organizing we could have supported if we had treated them with respect.

Alright, there are plenty of people who know this, and I can hear them into the peanut gallery rolling their eyes at the obvious point and congratulating themselves on how on-point their politics are. Good for you.

The trouble is, not everyone knows this, and vague denunciations of authority from angry punks do not always persuade the larger group. The police are tricky, and they know how to present a friendly face as well as their real one. In ‘War in the Neighborhood’, we see the cops put pressure on squatters by offering them a deal. The squatters, divided by the proposal, eventually accept. Needless to say, they are betrayed by the police.

Some of the people at Occupy knew better than to waste time talking to the cops, but many did not. The police could make little demands about where we put our tents or how we hung our tarps, and sow division without working very hard– these petty demands caused us to turn against each other. They were going to evict us eventually either way but the conflict over whether or not to comply with these petty demands created real conflict between us.

The police are not all billy clubs and tear gas. They will make little helpful gestures to win your trust. At one Occupy march, I remember them sharing bottled water with us. But by then we were wise – “Ew, cop water,” was how one friend put it. Earlier we had not always been so savvy. The police’s polite request to ‘liaise’ (read: pump us for information) or offers to protect our marches (read: control and contain our protests) convinced some people that they were on our side. When they swept into the camp in the middle of the night, tore down our tents and brutalized one of our friends, they made it perfectly clear whose friends they were.

I wish we had all known well enough to be on the same page, and understood the role of the police in suppressing resistance.

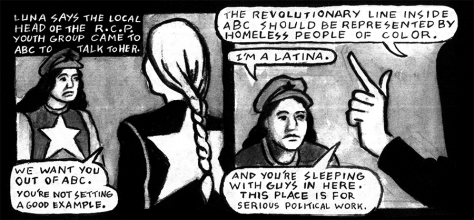

The left is full of self-appointed leaders and self-anointed messiahs. Academics, vanguard parties, one-man black blocs and all kinds of people whose analysis is so pure that they get high on the fumes. These people will show up at your movement and tell you where it’s going, what path it’ll take to get there, and what kind of clothes you should wear for your media appearances. What they won’t do, generally, is the dishes – or anything else useful.

This isn’t so much a problem of ideology as of personality. Some people know how to be humble, pull together as a team and do their share of every kind of work. Some people are so convinced of their special genius that they think they are making the most important possible contributions by telling everyone else what to do and think.

‘War in the Neighborhood’ shows us both kinds of people. Luna, a member of the RCP, becomes one of the most persistent and dedicated squatters. An angry anarchist denounces her participation and the squat as a whole because they are, presumably, guilty by association. Eventually, Luna herself leaves the party over its homophobic views and controlling nature.

When Occupy enjoyed its brief historical moment, plenty of groups wanted to control it. They showed up with their critiques, their literature, sometimes even with printed t-shirts. They would try to change the way Occupy was governed, or how it framed its messaging. Some were a problem, but others weren’t. At the end of the day, it didn’t matter so much what group they were from. What mattered was how willing they were to set their personal politics aside and work for the collective good of the group, instead of trying to co-opt it to serve their own purposes.

It can be a lot to keep track of, especially for folks who are new to activism. But I wish I’d known then what I know now – people show you how much you can trust them based on how respectful and committed their participation is.

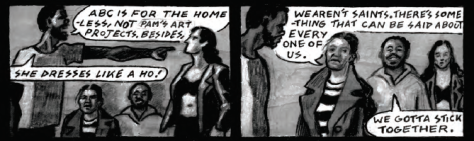

…but you can find out, easily enough! People vote with their time and energy. Look to see who’s putting in the work and who’s standing around talking shit. In ‘War in the Neighborhood’, we see a variety of people, including communists, ex-cons, teenage anarchists, people with active addictions and the homeless prove to be the best of comrades.

That is not always intuitive. It is easy to be drawn to the most articulate people, or the ones who seem to have the most support in the group. You can be taken in by people’s charms or by the appearance of experience. In the end, though, it doesn’t matter how articulate someone is, how experienced they are, or how great their analysis is, if they can’t put their own agenda aside and work as part of a team.

At Occupy I definitely had a preference for people who shared my politics and cultural values most closely. But I learned in time that I valued the friendships of all kinds of people – liberals, social democrats, other anarchists and even 9/11 truthers (thanfully, those guys came around).

Of course, we were working inside an anarchist framework, with a set of anarchist assumptions. Over time, I watched a lot of those folks evolve into the best anarchists I know. But I think this point holds true no matter what the ideology of your group. If people focus on the work, it doesn’t matter where they’re coming from. You’re headed the same way.

Rules are a recurring theme for ‘War in the Neighborhood’. Should this squat be drug free? Should we negotiate with the cops? Are we prepared to tolerate sexism? In different ways these questions are all part of the bigger question: “How will we make this space our own?” and “What is this space for?” But while everyone agrees with ‘making this space our own’, they can’t even agree what that looks like.

At my Occupy camp, and I suspect at many others, the problem was worse, if anything. Should we march? Should we build the camp? Should we make signs? Should we make dinner? Again, holding the park was just about the one thing we all agreed was necessary.

This was a real shock to me. I arrived thinking that people would more or less be there for the same reason I was – tired of the growing power of the rich and ready to hold them to account. The reality was not so simple. I wish I had been able to better anticipate that.

There were some people who were not so ready to accept the riot of ideas and ideology on display at Occupy. I couldn’t believe them. I was putting aside a lot of my own ideas about how the world should work out of some abstracted sense of the common good. Why couldn’t they do the same?

People have agendas. They look at social movements and they ask themselves if these social movements serve those agendas. Then they decide if they are going to participate, criticize, or both. If your revolution doesn’t look like it’s going to serve their purposes, don’t expect to see them frying tofu in the kitchen tent.

“War in the Neighborhood” shows us that people have different reasons for wanting you to fail. Maybe they don’t like some of your members. Perhaps they disagree with your group’s tactics. Maybe they didn’t get their way in your group and so they left.

Maybe I should have known this one before Occupy started. I thought I knew it, really. I thought I knew that things were so close to hopeless that it would take a change in world conditions to create an opportunity for change. But then in Occupy I saw that opportunity.

In a way, all social struggles have the potential to make us feel like everything has changed. ‘War in the Neighborhood’ shows impossible victories – people taking over abandoned buildings, neighborhood people fighting back against police violence, homeless people winning the right to maintain a tent city in Tompkins Square Park.

But even when all the rules of normal life seem to be inverted, there are no easy answers. You can fight like hell and do everything right only to watch it all fall apart because of some unhappy accident. We are still learning, all of us struggling to build a better world. I don’t think anyone has all the answers. But if we could get better at telling stories about what went right – and what went disastrously wrong – we might not be quite so completely doomed to repeat our history forever.

As we run our most recent crowdfunding project, we have taken a dive into the history of squatting as a practice of anti-capitalist resistance. In many parts of North America, it’s difficult to conceive of squatting as anything other than a romantic ideal – except for the fact that settler societies are squatter societies by nature, albeit of an objectionable variety. Meanwhile in Europe there are vibrant squatters’ movements in the Netherlands, Greece, Germany and many other countries. What’s the secret to their success? You might find a few clues in the books below.

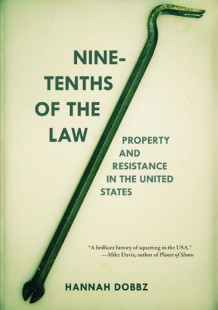

1. Hannah Dobbz – editor of “Nine-Tenths of the Law: Property and Resistance”

1. Hannah Dobbz – editor of “Nine-Tenths of the Law: Property and Resistance”

From AK Press, the publisher: “How does “property” fit into designs for an equitable society? Nine-Tenths of the Law examines the history of squatting and property struggles in the US, from colonialism to 20th-century urban squatting and the foreclosure crisis of the late 2000s, and how such resistance movements shape the law. Squatting is defined by Dobbz as “occupying an otherwise abandoned structure without exchanging money or engaging in a formal permissive agreement.” Stories from our most hard-hit American cities show that property is truly in crisis.”

2. Squatting Europe Kollective – “The Squatters’ Movement in Europe: Commons and Autonomy as Alternatives to Capitalism”

From Pluto Press, the publisher: “The Squatters’ Movement in Europe is the first definitive guide to squatting as an alternative to capitalism. It offers a unique insider’s view on the movement – its ideals, actions and ways of life. At a time of growing crisis in Europe with high unemployment, dwindling social housing and declining living standards, squatting has become an increasingly popular option.

From Pluto Press, the publisher: “The Squatters’ Movement in Europe is the first definitive guide to squatting as an alternative to capitalism. It offers a unique insider’s view on the movement – its ideals, actions and ways of life. At a time of growing crisis in Europe with high unemployment, dwindling social housing and declining living standards, squatting has become an increasingly popular option.

The book is written by an activist-scholar collective, whose members have direct experience of squatting: many are still squatters today. There are contributions from the Netherlands, Spain, the USA, France, Italy, Germany, Switzerland and the UK.”

3. Nazima Kadir – “The Autonomous Life? Paradoxes of Hierarchy and Authority in the Squatters Movement in Amsterdam”

From Manchester University Press, the publisher: “ ‘The Autonomous Life?’ is an ethnography of the squatters’ movement in Amsterdam written by an anthropologist who lived and worked in a squatters’ community for over three years. During that time she resided as a squatter in four different houses, worked on two successful anti-gentrification campaigns, was evicted from two houses and jailed once. With this unique perspective, Kadir systematically examines the contradiction between what people say and what they practice in a highly ideological radicalleftcommunity. The squatters’ movement defines itself primarily as anti-hierarchical and anti-authoritarian, and yet is perpetually plagued by the contradiction between this public disavowal and the maintenance of hierarchy and authority within the movement. This study analyses how this contradiction is then reproduced in different micro-social interactions, examining the methods by which people negotiate minute details of their daily lives as squatter activists in the face of a fun house mirror of ideological expectations reflecting values from within the squatter community, that, in turn, often refract mainstream, middle-class norms.”

From Manchester University Press, the publisher: “ ‘The Autonomous Life?’ is an ethnography of the squatters’ movement in Amsterdam written by an anthropologist who lived and worked in a squatters’ community for over three years. During that time she resided as a squatter in four different houses, worked on two successful anti-gentrification campaigns, was evicted from two houses and jailed once. With this unique perspective, Kadir systematically examines the contradiction between what people say and what they practice in a highly ideological radicalleftcommunity. The squatters’ movement defines itself primarily as anti-hierarchical and anti-authoritarian, and yet is perpetually plagued by the contradiction between this public disavowal and the maintenance of hierarchy and authority within the movement. This study analyses how this contradiction is then reproduced in different micro-social interactions, examining the methods by which people negotiate minute details of their daily lives as squatter activists in the face of a fun house mirror of ideological expectations reflecting values from within the squatter community, that, in turn, often refract mainstream, middle-class norms.”

4. Pierpaolo Mudu and Sutapa Chattopadhyay – “Migration, Squatting, and Radical Autonomy” Edited by P.M. and S.C. on behalf of the Squatting Europe Collective

From Routledge, the publisher: “This book offers a unique contribution, exploring how the intersections among migrants and radical squatter’s movements have evolved over past decades. The complexity and importance of squatting practices are analyzed from a bottom-up perspective, to demonstrate how the spaces of squatting can be transformed by migrants. With contributions from scholars, scholar-activists, and activists, this book provides unique insights into how squatting has offered an alternative to dominant anti-immigrant policies, and the implications of squatting on the social acceptance of migrants.”

From Routledge, the publisher: “This book offers a unique contribution, exploring how the intersections among migrants and radical squatter’s movements have evolved over past decades. The complexity and importance of squatting practices are analyzed from a bottom-up perspective, to demonstrate how the spaces of squatting can be transformed by migrants. With contributions from scholars, scholar-activists, and activists, this book provides unique insights into how squatting has offered an alternative to dominant anti-immigrant policies, and the implications of squatting on the social acceptance of migrants.”

5. Lynn Owens – “Cracking Under Pressure: Narrating the Decline of the Amsterdam Squatters’ Movement”

From Penn State University Press, the publisher: “Social movements excite and energize their participants in their early phases, with expectations high and ambitions yet unchecked by reality. Consequently, the academic study of social movements has focused primarily on the stages of mobilization and growth. But all movements eventually decline, and it is important to understand why they do, when they do, and what the effects of decline are.

From Penn State University Press, the publisher: “Social movements excite and energize their participants in their early phases, with expectations high and ambitions yet unchecked by reality. Consequently, the academic study of social movements has focused primarily on the stages of mobilization and growth. But all movements eventually decline, and it is important to understand why they do, when they do, and what the effects of decline are.

Lynn Owens aims to broaden and enrich social movement theory by focusing on this phase of decline. He does so through a close investigation of the fate of the squatters’ movement in Amsterdam, which emerged in the late 1970s as a reaction to the housing shortage of the 1960s, peaked in the early 1980s at some 10,000 participants, and then fell into a period of prolonged decline. As a movement significant for its influence on radical movements elsewhere in Europe and for its contribution to Amsterdam’s reputation as a center of countercultural activity, this case study affords an opportunity to examine not only why movements decline but also how—how activists respond to decline first by downplaying it, then by debating it, and finally by adjusting to it.”

5. Bart van de Steen – “The City is Ours: Squatting and Autonomous Movements in Europe from the 1970s to the Present”

From PM Press, the publisher: “Squatters and autonomous movements have been in the forefront of radical politics in Europe for nearly a half-century—from struggles against urban renewal and gentrification, to large-scale peace and environmental campaigns, to spearheading the antiausterity protests sweeping the continent.

From PM Press, the publisher: “Squatters and autonomous movements have been in the forefront of radical politics in Europe for nearly a half-century—from struggles against urban renewal and gentrification, to large-scale peace and environmental campaigns, to spearheading the antiausterity protests sweeping the continent.

Through the compilation of the local movement histories of eight different cities—including Amsterdam, Berlin, and other famous centers of autonomous insurgence along with underdocumented cities such as Poznan and Athens—The City Is Ours paints a broad and complex picture of Europe’s squatting and autonomous movements.”

6. Stephen Luis Vilaseca – “Barcelonan Okupas: Squatter Power!”

“From Rowman and Littlefield, the publisher: Barcelonan Okupas: Squatter Power! is the first book to combine close-readings of the representations of Spanish squatters known as okupas with the study of everyday life, built environment, and city planning in Barcelona. Vilaseca broadens the scope of Spanish cultural studies by integrating into it notions of embodied cognition and affect that respond to the city before and against the fixed relations of capitalism. Social transformation, as demonstrated by the okupas, is possible when city and art interrelate, not through capital or the urbanization of consciousness but through bodily thought. The okupas reconfigure the way thoughts, words, images and bodily responses are linked by evoking and communicating the idea of free exchange and openness through art (poetry, music, performance art, the plastic arts, graffiti, urban art and cinema); and by acting out and rehearsing these ideas in the practice of squatting. The okupas challenge society to differentiate the images and representations instituted by state domination or capitalist exploitation from the subversive potential of imagination. The okupas unify theory and practice, word and body, in pursuit of a positive, social vision that might serve humanity and lead the way out of the current problems caused by capitalism.”

“From Rowman and Littlefield, the publisher: Barcelonan Okupas: Squatter Power! is the first book to combine close-readings of the representations of Spanish squatters known as okupas with the study of everyday life, built environment, and city planning in Barcelona. Vilaseca broadens the scope of Spanish cultural studies by integrating into it notions of embodied cognition and affect that respond to the city before and against the fixed relations of capitalism. Social transformation, as demonstrated by the okupas, is possible when city and art interrelate, not through capital or the urbanization of consciousness but through bodily thought. The okupas reconfigure the way thoughts, words, images and bodily responses are linked by evoking and communicating the idea of free exchange and openness through art (poetry, music, performance art, the plastic arts, graffiti, urban art and cinema); and by acting out and rehearsing these ideas in the practice of squatting. The okupas challenge society to differentiate the images and representations instituted by state domination or capitalist exploitation from the subversive potential of imagination. The okupas unify theory and practice, word and body, in pursuit of a positive, social vision that might serve humanity and lead the way out of the current problems caused by capitalism.”

Learn more here

7. Agnes Gagyi – “Hungary: The Constitution of the ‘political’ in Squatting”

From Baltic Worlds, the publisher:

“The idea of political squatting has been codified in the practice and self-reflection of Western European radicalizing movements, which turned, following the downturn of the 1968 movement cycle, to conflictual strategies in urban settings, to voice problems of housing, youth unemployment, and various countercultural values. In defining political squatting, researchers rely on these historical backgrounds to grasp the political dimension that makes squatting more than simple occupation. In doing so, they tend to raise elements of the Western European historical context as evident corollaries of the phenomenon. For example, in a new comparative study on Western European squatters’ movements in 52 large cities, Guzman1 summarizes the literature on political squatting, identifying typical elements of the political context of squatting in phenomena such as support by the New Left and the Greens, squats serving as platforms for the extra-parliamentary left, involving Marxists, autonomists, anarchists, and a left-libertarian subculture, and being part of campaigns for affordable housing or minority rights, or against war, neo-Nazis, unemployment, precariousness, urban speculation and regeneration projects, gentrification, and displacement”

8. Håkan Thörn et al – “Space for Urban Alternatives: Christiana 1971 – 2011”

From the Goteborg University website: “In 1971, a group of young people broke into a closed down military area in Copenhagen. It was located not more than a mile from the Royal Danish Palace and the Danish parliament. Soon, the media published images and reports from the proclamation of the Freetown Christiania, and people travelled from all over Europe to be part of the foundation of a new community. A ‘Christiania Act’ passed by a broad parliamentary majority in 1989 legalised the squat and made it possible to grant Christiania the rigth to collective use of the area. However, this was reversed under the Liberal-Conservative government in 2004 when the parliament decided on changes in the 1989 Christiania law. The Freetown has refused to give up its claims on the property so it remains highly contested. Around 900 people live in Christiania today. It is governed through a decentralised democratic structure, whose autonomy is strongly contingent on the Freetown’s external relations with the Danish government, the Copenhagen Municipality, the Copenhagen Police and to the organised crime in connection with the cannabis trade. This book brings together ten researchers from various disciplines; Sociology, Anthropology, History, Geography, Art, Urban planning, Landscape architecture and Political science to bring thier own reflections on the unique community that is Christiania. In the introductory chapter, the editors provide an overview of the research that has been done on the settlement from the early 1970s to the 2000s.”

Interested in learning about the history of squatting here in North America? Check out our pre-order campaign for Seth Tobocman’s ‘War in the Neighborhood’, a 300 pg account of squatting and the fight against gentrification on New York’s Lower East Side.