“A fierce discussion is taking place among the left internationally ever since Alexis Tsipras decided to capitulate to the demands of the Europeans and agreed to sign and implement a third Memorandum for Greece. The discussion centres mostly on whether the Syriza Government should have had a Plan B prepared for dealing with the results of a ‘Grexit’ should the negotiations fail. It is my contention that such a discussion misses the point and falls into the trap of presenting the issue as an opposition between remaining in the Eurozone and adopting a national currency. It is this opposition that was used as the weapon of choice both by the Greek and the European political elites to crush the Syriza Government. Instead of searching for a Plan B it is urgent to understand the objective nature of Plan A and assess its dynamic and potency.”

………………….

“. Whether the next clash will be between the Greek Government and its creditors or between Greek protesters and the police, Tsipras will again and again be called to make a decision on where to stand: on the side of Revolution or on the side of Reaction? This is why the Left, both inside and outside Syriza, should consider first the possibility of making the second option more difficult for him rather than pushing him there.”

Revisiting Plan A

What options for the Left in Greece after Tsipras’ climb-down?

By: Themos Demetriou, Nicosia 2015

A fierce discussion is taking place among the left internationally ever since Alexis Tsipras decided to capitulate to the demands of the Europeans and agreed to sign and implement a third Memorandum for Greece. The discussion centres mostly on whether the Syriza Government should have had a Plan B prepared for dealing with the results of a ‘Grexit’ should the negotiations fail. It is my contention that such a discussion misses the point and falls into the trap of presenting the issue as an opposition between remaining in the Eurozone and adopting a national currency. It is this opposition that was used as the weapon of choice both by the Greek and the European political elites to crush the Syriza Government. Instead of searching for a Plan B it is urgent to understand the objective nature of Plan A and assess its dynamic and potency.

The Syriza Government’s defeat in the hands of far superior forces masks the real strength of its negotiation tactics and misleadingly points to a lack of strategy that was bound to lead to a defeat. However, if we look beyond the harsh terms of the agreement we realise that the tactics of the negotiations are compatible with a revolutionary strategy for radically changing not only Greece but also Europe, and probably beyond. The first basic principle of this strategy is that Greece cannot make it alone. In order to succeed in getting rid of the Memorandum, European policies must radically change. The second principle is to make sure that the people, both in Greece and in Europe, stay informed and be kept on board and made aware that the efforts of the Greek Government were reasonable while the Europeans were unreasonable and vindictive. The third principle was to attempt to split the opposing forces. Whether these principles were consciously applied by Tsipras and Varoufakis or not, they were followed with reasonable precision and met with fair success. The insistence in the European scope of their goals was absolute, the transparency of the negotiations was unprecedented, leading to widespread support for the Greek position not only among the intelligentsia but also, more importantly, winning over public opinion both in Greece and in Europe. Driving a wedge between the ‘Institutions’ came close to success with the Americans forcing the IMF to publish its report just before the Greek Referendum and the European Commission and France clearly perturbed by Schäuble’s Grexit plans.

Tsipras’ acceptance of the European ultimatum marks the end of this phase of the drama. Whatever our opinion about the wisdom of his decision, the real issue now is the correct assessment of the possibilities for left politics in Greece now. Gindin and Panitch are quite correct in opposing a hasty exit from the Eurozone demanded on the basis of Syriza’s failure to win in their negotiations with the European elites. They base their view on the fact that it is exactly Syriza’s intent to negotiate a deal within the Eurozone that won the election for them:

As for counselling Syriza to risk losing its governing status, it needs to be noted that Syriza already faced this question in the run up to the 2012 elections, and concluded that the responsible decision was to enter the state and do everything it could to restrain the neoliberal assault from within the state. Its electoral breakthrough that year was based on Tsipras’s declaration that Syriza was not just campaigning to register a higher percentage of the vote but determined to form a government with any others who would join with it in stopping the economic torture while remaining within Europe. It was only when it came close to winning on this basis that Syriza vaulted to the forefront of the international left’s attention and, by the following summer, Tsipras was chosen by the European Left Parties to lead their campaign in the 2014 European Parliament elections. Syriza’s subsequent clear victory in Greece in this election foretold its victory in the Greek national election of January 2015, when it became the first and only one of all the European left parties to challenge neoliberalism and win national office. [1]

Gindin and Panitch go on to argue for the necessity of Syriza staying in the Government despite the harsh measures they will have to take in accordance with the Memorandum requirements. They see no possibility of a successful exit from the Eurozone and no credible left alternative to the Tsipras leadership. Their advice to the Greek Government is to take a longer term view of the situation and try to expand on the theme of the social solidarity movement in order to create new forms of structures to counter-balance the terrible effects of the Memorandum.

The point we are getting at is that framing the issue in terms of an exhausted Plan A (negotiating with Europe) and a rejection of the euro (Plan B) is too limited a way to frame the dilemmas confronting Syriza. What the deeper preparation for leaving the Eurozone, and possibly also the EU, actually entails is to build on the solidarity networks that have developed in society to cope with the crisis as the basis for starting to transform social relations within Greece. That is the real Plan B, the terrain on which both Syriza and the social movements might re-invigorate now.[2]

This is of course interesting but obviously only part of a strategy. Gindin and Panitch see this as a preparation for a Grexit, a break with the oppressive powers that EU represents. Then what? Build half-socialism in Greece within the context of a hostile Europe? More to the point, is it feasible to keep and amplify the dynamic of the solidarity movement in a climate of general disappointment? And how are we to avoid the looming danger of a right wing backlash that could see Golden Dawn or the army taking power?

Modest Radicalism[3]

To understand today’s social dynamics it is necessary to assess what happened during the five months of Syriza’s rule until the fateful decision by Tsipras. Syriza was never a unitary party and it would be futile to attempt to lay responsibility for the actions of the Syriza Government on the Party. Policies were not formed through normal party discussions and conferences but were mostly decisions that went through a kind of democratic discussion but in the end responsibility for them was fuzzy and unclear. As opinions within Syriza varied widely, decisions were taken within a regime of intense arguments and contradictions with which not everybody was happy. Nevertheless, the ‘components’ of Syriza stuck together in their joint attempt to stem the misery of the Greek people imposed by the Memoranda and the Troika.

Notwithstanding the lack of effective formal democratic decision making procedures, Syriza did not degenerate into an autocratic structure. On the contrary, decisions at every step seemed to command the support of the majority of the Party members and certainly of the Party supporters. There was some grumbling on the left of the Party, but that was never a serious concern. In fact, the motley crowd that formed Syriza had forged a new kind of Party, one that could be far to the left of anything remotely mainstream and at the same time command the support of the masses. Integral to that Party was the complete freedom of expression, open discussion and the total lack of the need for a whip.

In retrospect it is easy to see why this was possible. The ‘radical’ policies that formed the essence of Syriza were very modest indeed. If we look at the Thessaloniki Programme we shall be amazed at the modesty of its proposals. Only a few decades ago such a programme would be the governmental programme of mainstream European Social Democracy. Pasok’s founding programme, The 3rd of September Programme, was far more radical and far reaching than anything discussed in Syriza since its formation. That programme included such ‘extreme’ demands as the ‘socialist transformation of society’ ‘worker’s control of the units of production’, ‘socialisation of the financial system in its totality, the important units of production and the big import and export trade’. It advocated ‘Free and compulsory education’, abolition of private education and participation of students in the planning of education and the running of teaching institutions. Some of these demands were even implemented during the Andreas Papandreou Government.

The Syriza demands were tame by comparison. In fact the immediate policies proposed by its various factions did not differ much. There were serious strategic differences, but these could wait. In practice, Marxists and Keynesians, reformists and revolutionaries could work together in what they probably perceived, consciously or unconsciously, as a medium-term alliance in opposing neoliberalism, austerity and the Memoranda. Sooner or later, this alliance was bound to face difficulties as the realities of the capitalist system started to force not simply painful compromises but the complete back-tracking of the Syriza Government with a punitive agreement everybody considers unrealistic in its implementation prospects.

What is going on? What is the qualitative change that makes a mainstream Social Democratic programme of the sixties and seventies a dangerous revolutionary manifesto in the twenty-first century? The most obvious answer is 2008. After nearly three decades of neo-liberalism and almost two decades after the fall of Stalinism the ‘New World Order’ hit the rocks and the ‘End of History’ was itself at an end. The collapse of neoliberal economics ushered in an epoch of instability for world capitalism, an epoch in which capitalism can no longer justify its existence except by the fact that it possesses the power to crush any opposition. As Paul Tyson, Honorary Assistant Professor of Humanities at the University of Nottingham, put it

…for big financial players and big governments, power is its own justification. This is called financial realism. All the Eurozone troika are doing in relation to Greece is following the American example of financial realism. Here, that which is legal, necessary and right is, in the final analysis, whatever the financial institutions with the most power tell you is legal, necessary and right. That their rules work in their interest is taken for granted. It is also understood that anyone who doesn’t play the game that they control, by their rules, will be punished severely.[4]

In this situation reformism cannot be tolerated by the ruling classes. Reformists of all persuasions, traditionally considered ‘traitors’ of the working class by Marxists, are pushed towards radicalism and find themselves forced to make a choice: either join the Revolution or become active oppressors of the working class. Even Keynesianism, the economic policy framework that worked wonders for post-war capitalist development, is today seen as highly toxic for today’s world order. The Spectator goes as far as blaming British universities for all the failures of peripheral capitalist countries to prosper.

Varoufakis was a product of British universities. He read economics at Essex and mathematical statistics at Birmingham, returning to Essex to do a PhD in economics. With the benefit of his British university education he returned to Greece and, during his short time in office, obliterated the nascent recovery. The economy is now expected to contract by 4 per cent this year — an amazing transformation. Greece’s debt burden has increased by tens of billions and many people have emigrated.

But Varoufakis is not alone. Plenty of other visitors to our universities have been influenced by the teaching here and returned to their countries to wreak havoc.

Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of an independent India, is understandably regarded by many as a hero. But unfortunately for that country he attended Trinity College, Cambridge. There he was influenced by British intellectuals such as George Bernard Shaw, a socialist, Bertrand Russell, who once remarked ‘communism is necessary to the world’, and John Maynard Keynes. He returned to India and started to put the ideology into practice with state planning, controls and regulations. This was a calamity. Following his rule, India’s share of world trade fell and a generation failed to emerge from abject poverty. Only when the ideology was abandoned with the free market reforms of the 1980s did India’s growth and amazing poverty-reduction begin.[5]

The article goes on to list Julius Nyerere (‘encountered Fabian thinking’ when he studied at Edinburgh ‘as did Gordon Brown’, probably another dangerous ‘socialist’), Robert Mugabe, Jomo Kenyata, Kwame Nkrumah, Pierre Trudeau (yes, the Canadian) and Zulfikar Ali Butto as examples of dangerous ‘socialists’ that ruined the economies of their countries. Their ‘failures’ had nothing to do with backwardness, imperialist aggression, military coups or foreign subversion – no, it was their ‘socialism’ or ‘Fabianism’ or ‘Keynesianism’ imbued in them by leftist British academics and their ‘ideological dogmatism’.

Notwithstanding the ostensibly tongue-in-cheek style of the article there is more than a grain of seriousness in what the Spectator says. It seems clear that the ruling classes are losing the ideological battle in the class war. They can no longer hold their ground on the premise of reason, or morality or even functional real‑politik. So, they ditch reason. Their only reasoning, by now unashamedly and openly argued out, is that they have the power (for the moment the economic power but with military power looming not far behind[6]) to suppress anybody who dares to challenge them. Democracy, freedom of speech, human rights are all expendable in the face of the all-powerful ‘markets’ and the need to protect the wealth and power of an ever decreasing miniscule minority.

We are reaching a point that any rational logic becomes a danger for the system. If we want a better life for the majority of the population, whatever we do we reach a point that it is not possible to do it without violently clashing with the ruling classes. Even modest reforms become revolutionary manifestoes. Slavoj Žižek expressed this accurately in the New Statesman:

What is so enervating about Varoufakis is not his radicalism but his rational pragmatic modesty – if one looks closely at the proposals offered by Syriza, one cannot help noticing that they were once part of the standard moderate social-democratic agenda (in Sweden of the 1960s, the programme of the government was much more radical). It is a sad sign of our times that today you have to belong to a “radical” left to advocate these same measures – a sign of dark times, but also a chance for the left to occupy the space which, decades ago, was that of the moderate centre left.

But, perhaps, the endlessly repeated point about how modest Syriza’s politics are, just good old social democracy, somehow misses its target – as if, if we repeat it often enough, the Eurocrats will finally realise we’re not really dangerous and will help us. Syriza effectively is dangerous; it does pose a threat to the present orientation of the EU – today’s global capitalism cannot afford a return to the old welfare state.

So there is something hypocritical in the reassurances about the modesty of what Syriza wants: in effect, it wants something that is not possible within the co-ordinates of the existing global system. A serious strategic choice will have to be made: what if the moment has come to drop the mask of modesty and openly advocate the much more radical change that is needed to secure even a modest gain?[7]

This is the background which allowed Syriza not only to gain power but also to remain united and avoid splits that plagued leftist parties and groups in previous decades. Syriza’s modest radicalism was based in the need to join forces in the face of a demanding objective situation requiring urgent action to combat the social and humanitarian crisis perpetrated by the austerity policies imposed on Greece. It is this background that made possible the coexistence of such a varied bunch people in the struggle to implement a programme in which everyone believed. A programme that expressed the hopes of all the ‘constituents’ and at the same time expressed the hopes of the Greek people too. The Thessaloniki Programme is what Trotsky would call a Transitional Programme in its most pure and effective form, without the stale dogmatic trappings we have been subjected to by Trotsky’s epigones. It is a programme that grew naturally out of the specific Greek realities of the time, not a vote winning ploy.

Syriza’s European Expedition[8]

When Syriza astounded everybody by coming a close second in the first elections of 2012 there was no coherent party programme for government. As a leading Syriza cadre put it at the time ‘we are not ready to govern but we must govern’. Had Syriza won the second election of 2012 the potential for a huge revolutionary upsurge would probably be unleashed. However, the lack of any preparation for such an eventuality would in all probability lead to chaotic developments. A race between putting together a viable policy and disaster would have been the reality for the following few months.

The Party was spared such a position of responsibility and at the same time it was shocked into the realisation that if they were to be serious they should put their act together. They very swiftly moved to improve their internal procedures in order to become a functional party, proceeded to put together a governmental programme, culminating in the Thessaloniki Programme, and paid more attention to their grassroots organisation nationwide. Internationally, they used their enhanced standing to forge relations with formations like Podemos in Spain and leftist organisations and parties in Europe and elsewhere. Not least, they attracted the sympathy of a wide range of intellectuals and academics who published prolifically on the work of Syriza, thus greatly increasing the world-wide attention to the Greek experiment. The choice of Tsipras as the candidate of the Left for the position of the President of the European Commission is indicative of the changes the rise of Syriza brought about.

By the time Syriza won the elections in January 25, 2015, a clear policy framework was in place, something that allowed them to quickly form a government and storm both Greece and Europe with an energy and effectiveness that surprised everybody. It is easy today for their detractors, both Right and Left, to present these actions as arrogant and futile, to ridicule them as the result of inexperience and the failure of theory but that would miss the achievements of the first five months of this Government and a failure to see how close it came to success. To see these five months as a period of ‘tactics but no strategy’ is only superficially correct but disregards the realities of the decision making process in Syriza and misses the essential correctness of the Greek stance from the point of view of a revolutionary strategy. The reality is that it is only from the perspective of a very radical strategic objective that the actions of Tsipras and Varoufakis in these five months can be understood and appreciated. Such a strategy was probably never formulated, or even formally discussed in Syriza but it was firmly in place during the negotiations. Its main aim was to win the Greek and European masses to the Syriza cause. Tsipras and Varoufakis seem to have been clearer than the rest of the Party on what they were after but the lack of a collective understanding on that led in the end to the collapse of their project. Tsipras could not in the end withstand the pressure and Varoufakis could not pull the Party to his point of view. Once the two fell apart, there was no way they could have continued their ambitious campaign. The Syriza decision making process had broken down.

It would be wrong to see Syriza’s strategy as a well-defined and detailed plan fully understood and supported by the Party. As most party decisions, the strategy was the result of intense discussion and contradictions and it was full of ambiguities. We can get a glimpse of the thinking behind the Greek Government’s actions if we follow the writings of Varoufakis himself. In a lecture originally delivered at the 6th Subversive Festival in Zagreb in 2013 he outlined his approach to radical politics:

In 2008, capitalism had its second global spasm. The financial crisis set off a chain reaction that pushed Europe into a downward spiral that continues to this day. Europe’s present situation is not merely a threat for workers, for the dispossessed, for the bankers, for social classes or, indeed, nations. No, Europe’s current posture poses a threat to civilisation as we know it.

If my prognosis is correct, and we are not facing just another cyclical slump soon to be overcome, the question that arises for radicals is this: should we welcome this crisis of European capitalism as an opportunity to replace it with a better system? Or should we be so worried about it as to embark upon a campaign for stabilising European capitalism?

To me, the answer is clear. Europe’s crisis is far less likely to give birth to a better alternative to capitalism than it is to unleash dangerously regressive forces that have the capacity to cause a humanitarian bloodbath, while extinguishing the hope for any progressive moves for generations to come.[9]

Here Varoufakis is distancing himself from the objective of socialist change as an immediate task of the left. Or is he? In that same lecture he goes on to explain why he is using non-marxist economic analysis to destabilise current economic thinking:

A radical social theorist can challenge the economic mainstream in two different ways, I always thought. One way is by means of immanent criticism. To accept the mainstream’s axioms and then expose its internal contradictions. To say: “I shall not contest your assumptions but here is why your own conclusions do not logically flow on from them.” This was, indeed, Marx’s method of undermining British political economics. He accepted every axiom by Adam Smith and David Ricardo in order to demonstrate that, in the context of their assumptions, capitalism was a contradictory system. The second avenue that a radical theorist can pursue is, of course, the construction of alternative theories to those of the establishment, hoping that they will be taken seriously.

My view on this dilemma has always been that the powers that be are never perturbed by theories that embark from assumptions different to their own. The only thing that can destabilise and genuinely challenge mainstream, neoclassical economists is the demonstration of the internal inconsistency of their own models. It was for this reason that, from the very beginning, I chose to delve into the guts of neoclassical theory and to spend next to no energy trying to develop alternative, Marxist models of capitalism. My reasons, I submit, were quite Marxist.[10]

It is important to note that Varoufakis did not confine himself in peripheral academic discussions on the subject but forcefully promoted his ideas far beyond the intellectual conference circle. His seminal work, The Global Minotaur, is one of the most easily understood analyses of the world economic crisis ever to be published. On a more nuts-and-bolts work, together with economists Stuart Holland and James K. Galbraith, they propose a very detailed economic programme for overcoming the European economic crisis with measures strictly within the legal and political framework of the European Union and the Eurozone. Is it a programme Varoufakis expected the Europeans to adopt and ‘save’ European capitalism from itself? I don’t think so. It is far more likely that the proposals are made in the spirit of exposing and destabilising the policies of madness perpetrated by the European institutions. A pointer to that effect is probably given by the very title of the proposals: A Modest Proposal. While it reflects accurately the contend of the proposals, one cannot miss the allusion to another, very political text, A Modest Proposal, by Jonathan Swift, written almost three centuries ago. That text leaves no doubt about its objectives. It is a caustic satire of the hypocrisy of Irish society that allowed poverty and suffering among the people while allowing the rich to live in luxury and ignore the agony of the poor.

The Thessaloniki Programme was a perfect tool for exposing the callousness of the European authorities. Having won the elections on its basis, the Syriza Government was ready to embark on the most ambitious attempt to change Europe since the inception of the European Union. An attempt to put an end to austerity and sweep away the total sway of neoliberalism and the rule of the super-rich. One cannot be sure whether they were fully aware of the implications of their attempt but they certainly knew that they were taking on a mighty opponent in an almost impossible task.

The first sign that the Syriza leadership meant business was the speed with which they proceeded to form a government. Instead of wasting time in tortuous discussions with the pro-memorandum Potami party or, worse, with Pasok they went ahead to form a coalition with Anel, a right-wing nationalist anti-memorandum party, too small to set the agenda in government policy but enough to set the tone of their anti-austerity emphasis. This avoided the pitfalls of new elections and allowed them to start contacts with the Europeans to feel the ground and plan the negotiations on the scrapping of the memorandum, as they promised the Greek people.

For almost a month, Tsipras and Varoufakis stormed Europe in an unprecedented tour de force around European capitals promoting their seemingly innocuous plans for renegotiating the loan agreement. Their realistic and modest suggestions provoked derision, something no one could reasonably understand. All they wanted was to reach an agreement that would promote necessary reforms to fight corruption and tax evasion and try to correct the ills of Greek society, put in place measures to tackle the unprecedented humanitarian crisis that the economic crisis inflicted on the Greek people and finally ensure that Greece’s creditors get at least some of their money back through decisions that would make the Greek debt viable. This last issue was a red line for Schäuble but in reality everybody knew that the Greek debt servicing was unsustainable – as the IMF report subsequently showed.

The Greek campaign attracted unprecedented world media attention, becoming headline news for the whole of the three weeks leading to the 20th February agreement and beyond. Between the endless reports on Tsipras’ ties and Varoufakis’ leather jackets, the serious staff was no less interesting. Not only to the politicians and the experts, but to the man in the street too. The Greek leaders made sure that they presented clearly to the public what was going on behind closed doors. And they presented it in a language understandable to everybody, both in Greece and in Europe and the rest of the World. Varoufakis seemed more interested in talking to the public than to his interlocutors in Brussels or Berlin. Tsipras was very frank in his televised briefings of the Syriza parliamentary group. Their behaviour was designed as if it was aimed at reaching public opinion, both in Greece and Europe, rather than convincing the finance ministers of the European countries who were not prepared even to listen to what the Greek Government was proposing.

The content of the agreement should not be the only factor determining the success of the Syriza negotiators. Their goals were going much further than that. They knew that their only allies would be the Greek and European masses; that they had to make an impact on public opinion and change the agenda of discussion. Their negotiation strategy was not simply to argue out their case in order to convince their European counterparts but to argue it out in full view of the public, to make it the subject of the everyday discussion of common folk.

By 20th February, less than a month after winning the elections, the Syriza negotiators reached an agreement with the ‘Institutions’ on the framework of the negotiations to follow. This agreement was a controversial document, full of ‘constructive ambiguities’ that allowed each side to claim success. Of course, in any conflict ambiguities will favour the stronger party and this was no exception. The ‘Institutions’ proved too strong for the Greek Government and in the end dictated policy to the last detail. Perhaps, the most pernicious clause in the agreement was the obligation of the Greek Government to avoid taking any measures with fiscal consequences, with the ‘Institutions’ deciding what had and what had not such consequences. This clause, probably more than anything else, was instrumental in virtually paralysing the Greek Government in the following months.

A war of attrition followed the agreement of the 20th of February. The Europeans blocked each and every legislation or action the Greek Government wanted to take. They were demanding more and more concessions and whenever Syriza retreated they were shifting the goal posts demanding even more. They were not prepared to concede even miniscule reforms, let alone anything that alluded to the Thessaloniki Programme. Their stance was increasingly political and soon it became clear that they were not after an agreement but after a change of government. They were themselves clear that a Syriza Government was a danger for everything they represented, a danger to European capitalism as we know it. In order to bring down Syriza they were prepared to shed one after another the very values they were supposed to profess. Democracy, human rights, social cohesion, elections, discussion, reason – all went down the drain. What remained was just ‘rules’ that had to be applied by order of the German Finance Ministry even when they made no sense at all.

By the end of June the retreat of the Greek Government was almost complete. Nothing but a few vestiges of the Thessaloniki Programme remained. At that stage, the European bureaucrats decided that it was time to present the Greek Government with an ultimatum: either they would accept everything the ‘Institutions’ were demanding or face dire consequences. By then Greek banks ran dry of money because of a huge deposit flight and Greece was faced with forced closure of the Banks and total financial suffocation by the cutting off of ELA by the European Central Bank. To everybody’s surprise, the Greeks did not succumb. They called a referendum for the 5th of July to let the people decide whether to accept the ultimatum, the Government advising a NO vote. The banks were promptly shut down and European officials started openly to threaten Greeks that if they voted NO Grexit would be the outcome with untold suffering of the Greek people.

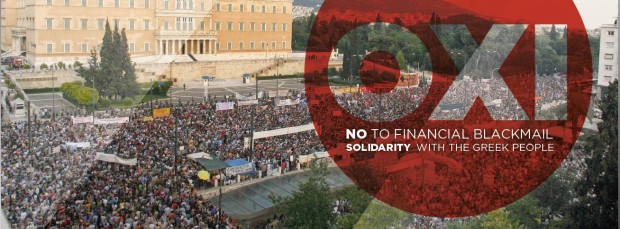

In the face of this open blackmail, in the face of a scare campaign by the Greek opposition parties and the subservient Greek press and other media, with the banks closed and capital controls slammed in place, the referendum returned a 61.3% NO vote. The Greek people had the fighting spirit to resist the whole of the European and Greek neo-liberal political and economic establishment and reassure the Greek Government that they were prepared to support it in its clash with superior forces despite the difficulties. The result of the referendum is proof, if one was needed, that business was not as usual for Greek capitalism; that revolutionary processes were fermenting underneath the political posturing in the Greek Parliament and the European institutions.

Capitulation

The elation of the left worldwide from the 5th of July triumph did not last long. It was clear that something was badly amiss when on the following morning Varoufakis offered his resignation considering it his ‘…duty to help Alexis Tsipras exploit, as he sees fit, the capital that the Greek people granted us through yesterday’s referendum’. One would expect that the logical thing for Tsipras to do was to send Varoufakis back to the Eurogroup with the last parcel of Greek proposals that they rejected and ask them to negotiate on it. After all, they themselves had originally judged it to be a good basis for negotiation. Incredibly, Tsipras decided that there was no life outside the Euro and stated his willingness to start negotiations on a variant of the EU ultimatum, as Junker had rendered it before the referendum. Varoufakis’ departure was just another gesture of appeasement to Greece’s creditors.

The German Finance Minister did not miss the significance of Tsipras’ turnaround. It was a clear signal that the Greek Government had lost the will to resist. It was also betraying the main reason for their capitulation: fear of leaving the Euro. Wolfgang Schäuble in the first meeting of the Eurogroup after the referendum pounced on his prey at its most vulnerable. He suggested a temporary exit from the Euro for Greece, a ‘time-out’. For the first time in the negotiations Grexit was official policy, openly suggested by the most powerful country in the European Union. From there it was all downhill for the Greek Government. They had to, and did, accept what they had rejected only a few weeks ago, and more, in order to bring back any agreement, in order to continue to exist. Having forgone any means of resistance, they had to accept whatever they were told in full knowledge that it was unworkable, that it was disastrous for the Greek people, that it was the beginning of the end of Syriza’s Government and Syriza itself. The Party that came to power with the promise to end the memorandum had signed to become the vehicle for implementing its third, more vicious reincarnation.

Back in Greece confusion reigned. Had the turnaround occurred at any time before the referendum it would be understandable, either in terms of the KKE’s view that Syriza was just another cog in the EU imperialist machine or New Democracy’s and Pasok’s narrative that there is no alternative. Calling the referendum had shattered both these versions. Now, they were coming back with a vengeance. But then, why the referendum? As the bitter joke goes, the Greek people were asked if they wanted the ultimatum’s measures to be accepted and they answered ‘no, we want more’.

Varoufakis’ explanation of the climb-down points to the lack of a solid collective understanding within Syriza of the strategic implications of their actions. What up to the point of the referendum was the glue that held Syriza’s components together, suddenly became its greatest weakness. As long as the discussions in Europe could be seen as a battlefield, as long as resistance to the ‘Institutions’ continued, Syriza held together admirably. When the moment of truth arrived, the common ground simply evaporated.

On the night of the referendum I entered the prime ministerial office elated. I was travelling on a beautiful cloud pushed by the beautiful winds of the public’s enthusiasm for the victory of Greek democracy during that referendum. The moment I entered the prime ministerial office I sensed immediately a certain sense of resignation, a negatively charged atmosphere and I was confronted with an air of defeat which was completely at odds with what was happening outside and at that point I had to put it to the prime minister ‘if you want to use the buzz of democracy outside the gates of this splendid building, you can count on me. If on the other hand you feel you cannot manage, you cannot handle this majestic no to a rather irrational preposition from our European partners, then I am going to simply steal into the night’. And I could see that he didn’t have what it took sentimentally, emotionally at that moment to carry that no vote into Europe to use it as a weapon. So I, in the best of all possible spirits, the two of us get along remarkably well and will continue to get on, I hope, I decided to give him the leeway that he needs in order to go back to Brussels and strike what he knows to be an impossible deal, a deal that is simply not viable.[11]

Varoufakis even claims that the Referendum was his own, personal idea:

Was it your idea personally to hold a referendum to ask the Greek people to vote on the conditions of this latest bailout?

Absolutely. And I’m exceptionally proud to have been part of a government that did what a democratic government has no alternative but to do. Let me put it very simply to you: on 25th June in a Eurogroup meeting, when I was still Finance Minister, I was presented with a comprehensive loan package as well as reform package for the Greek economy. We studied it very carefully and I asked myself and my colleagues asked themselves a very simple technical question: is this manageable? Is this viable? And I asked my partners in Europe: do you think this is viable? If we agree to this, are we going to turn the corner? Are we going to be able to repay the new debt that we are piling up on existing debt? And the answer we all gave, including the Institutions, including the International Monetary Fund, in all truth and honesty, was “No”. So we didn’t have a mandate to agree to effectively an ultimatum that wouldn’t render the Greek economy sustainable. And at the same time we didn’t have the mandate to cause a rupture with Europe. So what did we do? We put it to the Greek people and we said, “Well, this is the best deal we could bring back from Brussels and we are putting it to you. We are giving you all the facts and the figures and we’re asking you to exercise your responsible democratic right and tell us whether you want this deal or not.” And yet, Europe, or official Europe, in its infinite wisdom, decided that this was an unacceptable act on our part; that it was highly irresponsible to put to the Greek people a proposal that was put to us. That is a sad statement on the state of European democracy, I believe. [12]

These statements by the ex-Finance Minister of Greece give a rare glimpse into the workings of inner life in Syriza. The Coalition of Radical Left was just that: a coalition. As such it did not have a fully worked out long term programme, it was forging its policies through intense discussion among its various strands. A consensus could be reached on short term programmes, policies and tactics despite underlying differences. The force however that kept these differences at bay was the necessity to serve what they all believed in: their promise to secure a better life for the less fortunate vast majority of the Greek population. They could not break that promise, given the trust this majority placed in their Party catapulting it from a party of just over 4% to Government. Even now, after the capitulation of Tsipras and the harsh criticism of the agreement by the Left Platform, no one is eager to split the Party and destroy the dreams of the whole country and the European and international left.

Reform, Revolution and Socialist transformation

Syriza deployed quite a large spectrum of leftist tendencies ranging from the revolutionary far left to the outright reformist. Far left groups have tried repeatedly in the post-second world war period to create ‘mass revolutionary parties’ and prepare for the Revolution. They failed miserably in their attempt to attract workers to their cause and remained mostly small groupings working out programme after programme on the road to Socialism. Their failure usually led to extreme sectarianism and infighting that prevented any cooperation between them. The lack of any serious social basis denied them the possibility of grassroot accountability, something that often resulted in splits and perpetuated the fragmentation of the ‘revolutionary’ left.

Syriza provided a useful incubator for left wing politics. It operated a virtually open door policy of entry and exit of revolutionary tendencies, leftist intellectuals and other individuals. When Pasok betrayed the hopes of the Greek people that gave it an electoral win of almost 44% and entered into coalition with New Democracy under Papademos, Syriza was the obvious alternative on the left. By 2012 the party was a serious contender for the Government with Pasok voters turning to Syriza by the thousands. Inevitably, the new make-up of Syriza’s voters was partly reflected in the leadership. Reformists of all sorts flocked into the ranks of Syriza and claimed a share in the decision making process.

Syriza’s tendencies were roughly grouped in three categories. The Left, mainly consisting of revolutionary groups and Marxist intellectuals, the Right, probably a majority, following a more conventional agenda and a centrist leadership under Tsipras. The latter usually balanced between the other two groups calling the shots in the decision making process. One should not see this as an opportunistic stance but as a genuine way of finding common ground in a fast-developing and demanding situation. The differences were not stemming from personal rivalries but were real, political differences that needed resolution in order to move forward.

This classification however is far too rough to give an accurate idea of what Syriza was. Real life politics is too complex to be just assigned a left-right label. Varoufakis himself is a good example of such complexities. He was a late addition to the Syriza personnel and was considered by the Left as probably one of the most right-wing reformists in the party. His passionate opposition to exit from the Euro placed him, confusingly, alongside the ‘Eurolovers’ of New Democracy, Pasok and Demar. Yet, he turned out to be the most consistent, passionate and effective fighter for the ending of the memoranda and quit his post as a Minister rather than sign what he considered an unacceptable deal.

In fact Varoufakis seems to have provided the backbone to the Greek negotiation strategy and carried Syriza along with him. True to his beliefs he did not consider possible at that time a change into a better, socialist, system. So he set out in a course of changing European policies, a course that looked as if he was trying to convince or to threaten European leaders into such a change. Most analysts thought that his real threat was Grexit and the problems that would cause to the financial stability of the Eurozone. As mentioned above, this is a very superficial view. His most important threat was the realization by the Greek and European peoples of what the realities of the European project are and their mobilization into changing these realities. In this last attempt he was triumphantly successful. The whole discourse about European integration has changed radically. Europe will never be the same again.

The Syriza Government experience is essentially a new exercise in strategic planning for radical politics. History never waits for revolutionaries to work out the perfect plan with all the possible contingencies before it moves. Neither does it move when the plan has been worked out and printed in neat booklets. Political actors have to forge policies as events unfold, as needs arise. To paraphrase Marx, people write their own history, but not in conditions of their own making. It is futile to have a detailed plan of what must be done unless we know the details of the specific situation. This cannot be done in advance. Every situation is so complex that we cannot predict the exact conditions except in very general terms. Historical experience shows that revolutions wreak havoc with the plans of revolutionaries. Any plans made before the revolution breaks out are virtually useless unless radically adjusted to fit the realities of the moment. Strange as it may seem, probably the best example of this is Lenin himself. In January 1917, barely more than a month before the Russian February Revolution, he spoke to a meeting of young workers in the Zurich People’s House and said:

We of the older generation may not live to see the decisive battles of this coming revolution. But I can, I believe, express the confident hope that the youth which is working so splendidly in the socialist movement of Switzerland, and of the whole world, will be fortunate enough not only to fight, but also to win, in the coming proletarian revolution.[13]

Just three months later he was in Russia proposing his famous April Theses which constituted a complete overhaul of the programme of the Bolshevik Party. In July 1917 the Bolsheviks, despite refusing to support the Provisional Government, opposed the call for its overthrow realising that the working class was not yet ready to take power. Nonetheless, they took part in the uprising side by side with the masses while at the same time explaining that such an uprising was wrong at that time. After the defeat of the uprising Lenin went into hiding in Finland and Trotsky faced prosecution in the courts. While in hiding Lenin wrote State and Revolution, arguably the most libertarian of his texts. In late August the chief of the Russian army, Kornilov, attempted a coup against the Kerensky Government. The Bolsheviks, despite their persecution, supported the Government in suppressing the coup. They went on to secure a majority in the Soviets of Workers and Soldiers and on October 25 took power.

This is hardly a story of a well thought out plan applied with precision. If we add to that the fact that all the crucial decisions were taken amidst strong controversies, we realise that it is only the successful tuning of Bolshevik policies with the changing mood of the masses that led to the successful taking of power. Even the critical decision to proceed with taking power on the 25th of October was publicly opposed by Kamenev and Zinoviev, two of the highest ranking cadres in Bolshevik party. In contrast to later Stalinist practice and despite the harsh criticism of their action by Lenin, the two were given ministerial positions in the first Bolshevik government.

Relating the story of the Russian revolution is relevant here because of its parallels with the development of events in Greece after Syriza’s victory in January. Parallels not in a superficial sense of specific actions but in the deeper sense of decision making within the process of a revolutionary rising of the people. It is only possible to understand the events during the Syriza Government if we consider them within the framework of a revolutionary process. Syriza’s win was not the result of normal parliamentary processes, it was the result of a people rising against the established order, Greek and European alike. A rising that has its roots back in 2008 with the Alexis Gregoropoulos protests and continued with huge rallies, general strikes, the Syntagma aganaktismenoi, violent demonstrations, pupil and student unrest – a mass movement that started as a spontaneous, Occupy style protest and morphed in 2012 into a very potent political-parliamentary mass drive to take power with Syriza at its forefront.

The real task of a revolutionary is not to draw up a programme for running society in a socialist way. The real task is to make the masses part of this planning, to raise the consciousness of the masses so that they understand the realities of the present state of affairs and chart their course to a better society. This is what Lenin and the Bolsheviks did between February and October 1917, this is what Syriza was very successful in doing up until the morning of the 6th of July when Tsipras threw in the towel and changed the course of history.

Could he have done otherwise? As always with counter-factual histories the answer must be cautious and full of conditionals. Any specific action triggers responses that cannot be predicted with any certainty. Soon, the alternative futures determined by this action fork into a multitude of possibilities leaving us with chaotic predictions of what would have happened if a different decision had been made. Nevertheless, at least one alternative course must be considered, if anything because it was the natural thing to do and was also very close to be the one chosen. What would happen if Tsipras had followed Varoufakis’ advice and ‘…used the buzz of democracy outside the gates… [and] …carried that NO vote into Europe to use it as a weapon’?

We should remember that by that time the rift between the Europeans and the Americans was becoming serious with the latter forcing the publication of the IMF report on the viability of the Greek debt before the Greek referendum. We should also remember that serious cracks were beginning to surface within the European front, with Berlin and Paris drifting apart. The European bureaucrats were already seriously worried by Schäuble’s intentions to force Grexit, worries that were primarily political and not only financial. In these conditions, a firm stand by Greece would certainly further destabilise the austerity discourse in Europe with a real possibility of a serious clash within the European establishment.

We can safely assume that Tsipras dismissed such possibility as unlikely, he feared that the result of following a defiant course would lead to financial suffocation of Greece ordered by Merkel and Schäuble and carried out by the ECB and the Eurogroup and that would lead to Greece leaving the Eurozone. He considered the future of Greece outside the Euro as catastrophic, with good reason. The Left Platform’s hope that with a national currency it would be possible to follow a different fiscal policy and succeed in competing in the world market is just that – hope. If Greece were to leave the Euro with the consent of the other Eurozone countries, it would be under strict conditions that would be as harsh, if not more so, as the present ones. If it were to leave defaulting on its debts the Europeans would be even harsher.

What then should we expect the Syriza Government to do? Having secured the support of the Greek people the case can be made that it could press immediately and demand to continue the negotiations starting with its latest proposals that were rejected by the Eurogroup. In all probability the Europeans would not respond positively and would turn off any financial or other assistance. Greece would then default on its loans and some stop-gap measure of the type Varoufakis described for overcoming liquidity issues could be put in operation and try to survive a bit longer. Meanwhile a wide ranging programme of legislation could be pursued in order to take control of the economy and redress the suffering caused by the crisis for the less well off. Nationalisation of the Banks, reform of the tax system, increase in minimum wages, halt of the privatisation process etc. would be welcome by the people and increase their support to the Government.

This of course is the short or, at best, middle term optimistic scenario. Such a government could only survive for a short time amid a hostile Europe, a hostile world. In this time the hope is that it would attract the support of the European masses and form an example for them to follow. A domino effect of the kind we witnessed a few years ago during the Arab Spring is not beyond the bounds of reality. Spain, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and probably others face problems very similar to Greece that could be overcome by such drastic measures. France, Britain and even Germany should not be considered immune to change either. In the context of such a European conflagration the future begins at last to look brighter.

If however Greece remained isolated the future would be bleak indeed. It would soon degenerate into a backward society, poverty and famine would be the order of the day. If the Syriza Government was not overthrown, either through some sort of unrest or outright military coup or even foreign intervention, it would itself probably be forced into increasingly autocratic measures and police repression that would make today’s ills seem benign by comparison. After all that was the fate of the Russian revolution after the failure to spread the Revolution to the rest of Europe and the rise of Stalin. While not condoning Tsipras’ capitulation, we should understand the sort of thinking that may have prompted him to follow such a course.

Is there Second Life for Syriza?

Political leaders sometimes make decisions that decide the course of history. Tsipras decision to capitulate may prove to be one such decision. The decision could have been different and the implications of this have been discussed briefly above. Varoufakis too thinks a different path was possible. When confronted with his previous belief that a collapse of Europe would ‘unleash dangerously regressive forces’ he answered:

I don’t believe in deterministic versions of history. Syriza now is a very dominant force. If we manage to get out of this mess united, and handle properly a Grexit …it would be possible to have an alternative.[14]

Here Varoufakis is displaying a rare understanding of the significance of the specific objective situation in decision making. What in 2013 was a bleak realization that the only possible result of the collapse of Europe would be a relapse to barbarism, was no longer as certain in 2015. Something had changed: Syriza became a ‘dominant force’.

Within Syriza the Left Platform is already attempting to put together a programme that would be incompatible with the Syriza Government’s continued existence. With elections on the cards for this Fall they are contemplating a split to contest them on a radical programme of opposition to the agreement with Greece’s creditors. While this would probably attract a sizable portion of Syriza cadres, it is questionable that it would represent a significant proportion of today’s Syriza supporters. We should not forget that the jump from four to forty percent did happen overnight. The new supporters were won to the Thessaloniki Programme, not some outlandish socialist transformation project. The leaders they came to trust and love were Tsipras and Varoufakis rather than Lafazanis. The first could conceivably win the crowds to a socialist programme, something very doubtful in the case of the latter. This is even truer of European societies following the Greek drama with unabated interest.

The Left Platform is not a coherent crowd either. Within Syriza they can be a formidable force, they can display a fairly strong collective will. It is however doubtful if this can continue once they lose their binding agent, their opposition to the Party leadership. Once outside, divisions will start to surface. They will be of course able to concoct a common platform for the elections and their experience within Syriza would help them to run a collection of tendencies as a Party. If however they fail to make an impact, if they regress to a 4% grouping, their most probable future is fragmentation and disintegration. In such a scenario, and if no other serious left forces remain in the Party, the Syriza leadership will most likely move more to the centre, slowly but surely becoming integrated into the neoliberal capitalist project.

Things need not however go down that road. Tsipras and his government are in all probability not yet comfortable with the policies forced on them by the European and Greek ruling classes. They are still strongly bound to their Party and the masses who voted for them. Implementing the new memorandum will not follow a smooth path. If there is something almost everybody agrees is that the agreement is unworkable. New crises lurk at every turn of events. Whether the next clash will be between the Greek Government and its creditors or between Greek protesters and the police, Tsipras will again and again be called to make a decision on where to stand: on the side of Revolution or on the side of Reaction? This is why the Left, both inside and outside Syriza, should consider first the possibility of making the second option more difficult for him rather than pushing him there.

Of course a split in Syriza is not something intrinsically evil. If there is a social basis for such a split, if there is a real possibility that a new formation with a better programme and the ability to rally the masses can replace it, it would be the duty of the left to split. In the present conditions this seems more of a fantasy rather than a reasonable perspective.

Themos Demetriou

14 August 2015

Postscript

No sooner this text had been finalised and Tsipras submitted his resignation to the President of the Greek Republic and asked him to dissolve Parliament and call early elections. The members of the Left Platform promptly left the Syriza parliamentary group and announces the formation of a new Party under the name Popular Unity in order to contest the elections on an anti-memorandum platform.

These events seem to move in the direction of the most pessimistic scenario for the future of Syriza as a Party of the left. Tsipras seems determined to purge the Party from the irritating voices reminding him of last year’s march of hope and the MPs of the Popular Unity are taking a high risk gamble pushing him in that direction in the hope of replacing Syriza as a real force in the Greek left.

One can only hope that the magnificent force that was Syriza in the last period does not disintegrate completely under the burden of defeat and a new left emerges that will take at heart the lessons of the defeat and pick up the battle against austerity, neoliberalism and capitalism.

Meanwhile, in the rest of Europe there are encouraging signs for a resurgence of the left to replace the rise of right wing extremism as a result of the madness of austerity and neoliberalism. Syriza’s battle may still prove to be the harbinger of change in this new era of capitalist instability.

21 August 2015

[1] Sam Gindin and Leo Panitch ‘The Real Plan B: The New Greek Marathon’, Socialist Project, E-Bulletin No. 1145, July 17, 2015.

[2] Ibid.

[3] The term was coined by Olga Demetriou. See her ‘Modest Radicalism in the light of events in Greece’ a presentation at a Cypriots’ Voice Symposium on 5.3.2015. For an early treatment of the subject see my Reform and Revolution in the 21st Century: Understanding the Present Situation in Greece, March 2015

[4] In favour of Varoufakis’ Plan B, by Paul Tyson, http://yanisvaroufakis.eu/2015/08/01/in-favour-of-varoufakis-plan-b-by-paul-tyson

[5] How British universities spread misery around the world, James Bartholomew, The Spectator, 25 July 2015

[6] Of course, this is the benign, European version, of the story. The view is quite different from the vantage point of Iraq, Libya, Syria etc.

[7] Slavoj Žižek on Greece: This is a chance for Europe to awaken, New Statesman, 6 July 2015

[8] In my March analysis of the Greek situation, titled Reform and Revolution in the 21st Century, I drew the parallel between Varoufakis role in the negotiations with the Europeans and Alkibiades’ inception of the 415 BC Sicilian Expedition by Athens. Subsequent events strongly reinforce this parallel.

[9] Yanis Varoufakis: How I became an erratic Marxist, The Guardian Wednesday 18 February 2015

[10] Ibid.

[11] Varoufakis interview with Phillip Adams, http://yanisvaroufakis.eu/2015/07/14/on-the-euro-summit-agreement-with-greece-my-resignation-and-what-it-all-means-for-greece-and-europe-in-conversation-with-phillip-adams/

[12] Varoufakis interview to Emma Alberici, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-07-23/interview-yanis-varoufakis/6644330

[13] V. I. Lenin, Lecture on the 1905 Revolution, delivered in German on January 9 (22), 1917 at a meeting of young workers in the Zurich People’s House.

[14] Yanis Varoufakis full transcript: our battle to save Greece, New Statesman, 13 July, 2015

Continue reading →

Print format (read all)

Coming to a city near you!

Coming to a city near you!