History

Forty Years of Socialist Feminism

FSP's ideas in action

by Megan Cornish

The civil rights movement that had defied the Southern police state in the 1950s sparked a national Black freedom movement that ignited every other oppressed group — women, Chicanos, Native and Asian Americans, gays — and the mobilization against the Vietnam War. Internationally, anti-colonial independence movements swept Africa. In 1959, Cuba brought socialist revolution to within 90 miles of the United States.

This dynamic time was a test for Marxists, who were accustomed to focus on the traditional labor movement. Most radical groups consciously or unconsciously identified the working class with the white males who dominated union leadership and heavy industry. How should socialists respond to the passionate new masses? The FSP was the first party to embrace these movements and grasp their potential.

Why? Because FSP's founders identified with and were part of these social upsurges. They linked their own rich experiences to the Marxist understanding that only the working class has the power to take humanity to the next level. Their genius was to see that most of the new movements were movements of workers — and the most exploited and militant ones at that. Although this perspective was groundbreaking, it flowed directly from the ideas of early socialist thinkers like Marx, Clara Zetkin, and the co-leaders of the Russian Revolution, V.I. Lenin and Leon Trotsky.

All these pioneers identified the most downtrodden as the engine of change, and Lenin and Trotsky both specifically discussed the huge gap in consciousness and readiness to move between the privileged and the most oppressed workers in imperialist countries like the U.S.

The FSP's founders left the Socialist Workers Party over the SWP's failure to recognize the inherently revolutionary character of the struggles for Black and female liberation. They also disagreed with the SWP majority of the time by believing that a genuine workers state was established in China after the 1949 revolution.

But they would not have left the SWP had they been able to continue fighting for their positions. They were forced to strike out on their own because of an anti-democratic clampdown on internal debate, and the FSP was born.

Black liberation and socialist feminism to the fore. The theory of revolutionary integration that FSP founders had proposed to the SWP in 1963 put forward the belief that the African American freedom struggle would grow into a movement to transform the whole system. The progress of the indomitable civil rights movement and the forming of the Black Panther Party confirmed this conviction.

FSP also predicted the women's liberation movement that exploded on the scene in 1969.

In a 1966 pamphlet called “Why We Left the SWP,” we explained that the leading role of women in the civil rights, anti-war and other movements was not accidental and pointed to their secondary place in the labor movement as “a significant factor in the history of union degeneration.”

The document went on to say that “the oppression and special exploitation of women is a burning injustice that intersects with every other political question and social movement.”

Trotsky's theory of Permanent Revolution discusses how in this political era even the most basic democratic demands can only be satisfied by socialism. Today, the unmet needs and linked issues of women, African Americans, other people of color, immigrants, and queers — the super-oppressed workingclass majority — are the fuel for the fight. The FSP calls its program based on these ideas socialist feminism.

Within its first year, FSP weathered a divide over how well our practice would stand up to our feminist principles — and the accepted norms for behavior in the Trotskyist movement. When Clara Fraser, one of the party's founders, decided to divorce her husband Dick, also a founder, he acted in a hostile fashion first inside the party and then in court. He contested custody of their son by charging her with adultery and unfit motherhood because she worked outside the home!

The party split, with the majority supporting Clara Fraser. Shortly afterward, the FSP briefly became all women. But soon other, more conscious men joined the party. Party men today are engaged feminists.

In 1967, Fraser and her close colleague Gloria Martin joined with young women from Students for a Democratic Society to create Radical Women. Begun in order to build women's leadership in the left and anti-war movements, RW broke new ground to become in turn the socialist wing of the feminist movement. In 1973, it formally affiliated with the FSP, and the party gained a sister organization.

Making an activist mark. FSP has always believed that our job was to build movements and raise demands that point to radical solutions. Here are a few of many examples.

We turned to Black women anti-poverty activists to jointly organize a campaign for abortion rights that led to legalization in Washington state three years before Roe v. Wade. We urged anti-war forces not just to demand “troops out now” but to come out for the just victory of the communist National Liberation Front in Vietnam over the U.S. aggressors.

FSP members spearheaded the post-McCarthyism reemergence of open radicals in the unions. In the first-ever strike at the University of Washington, we invented the fight for equal pay for comparable worth.

We were pioneers for gay liberation. We joined historic Native American struggles for fishing rights, against poverty and government persecution, and more.

Women FSP and RW members broke into nontraditional trades as bus and truck drivers, welders and sheet metal workers, painters, carpenters, railroad workers, firefighters and electricians. Fraser set up a landmark affirmative action program for women at Seattle City Light in 1974 — and then was fired for leading unorganized workers in an employee walkout. It took eight years, but with broad support she beat city hall and won her lawsuit for political ideology discrimination!

In the midst of these battles, the party continued to break new theoretical ground. We developed an analysis of gay oppression as a consequence of female oppression. We studied Lenin on the national question and related his work to the burgeoning Chicano movement. We concluded that while Chicanos don't constitute their own nation in the U.S., their oppression on the basis of race and their ties to Mexico destine them for prominence in the emancipation of the whole working class.

In 1981, comrades of color in the party and RW took a big step forward for the two groups by organizing themselves into a joint national caucus. The caucus evaluates and looks for ways to intervene in the people of color movements, develops its members as a leadership team, and helps to solve problems of race relations inside RW and FSP when they arise. Among Marxist parties, it is a unique body.

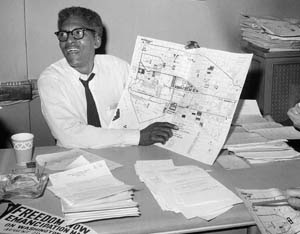

Engaging nationally and internationally. Having originated in Seattle, the FSP celebrated our tenth anniversary in 1976 with expansion to New York and Los Angeles, and branches in Portland and San Francisco soon followed. A vital part of reaching out nationally was the 1976 launch of the Freedom Socialist newspaper.

In the late 1970s, we helped initiate the Committee for a Revolutionary Socialist Party, an important attempt to unify with other Trotskyists. It included leftists from around the U.S. as well as a representative from the Moreno current of Latin American Trotskyism. Unfortunately, CRSP foundered over the question of feminism. But one of its members, Murry Weiss, a former longtime leader of the SWP, joined FSP and enriched our feminist and international analysis.

Meanwhile, the recessions of the '70s signaled an overall economic decline for world capitalism, with political reaction following inevitably. As the 1980s began, the U.S. entered the Reagan years, and labor and all the oppressed faced new attacks.

Such sea changes always produce both crises and opportunities for the Left. The question for the FSP was, how would the party respond to this challenge? Would we be able to maintain our program, principles and optimism for the socialist future? Starting in the late 1970s, U.S. working people and their organizations came under unremitting assault in a backlash against the social achievements of more than a century that continues to intensify to this day.

Funding for public programs was slashed. Union-busting became rampant. The racist "war on drugs" fueled a booming prison industry to house its many victims. Gains like affirmative action and abortion rights were barely won before they began to be eroded. Gay rights initiatives were ferociously opposed by a growing right wing. The income gap between rich and the not-rich widened apace.

Just as the FSP was integrally involved in the exciting upsurges of the 1960s and early '70s, we now found ourselves in the thick of both the attacks on the working class and defiant organizing against them.

In what was known as the Freeway Hall case, an eight-year saga kicked off in 1984 by a former member who attempted to force disclosure of confidential internal records, the party attracted support from labor, community, and civil rights groups and set a Washington state precedent protecting organizational privacy rights. Also in the 1980s, Asian American lecturer Merle Woo struck a historically resonant blow for free speech at the University of California at Berkeley by successfully challenging two discriminatory firings.

Meanwhile, modern-day fascists had decided to make the U.S. Northwest an Aryan homeland. The FSP took the lead in recognizing and responding to this threat.

We advocated a strategy of large, militant, face-to-face protests against public organizing by the Nazis, because this is the best way to discourage them — and they are not easily stopped once well on the way to becoming a mass movement. Seattle FSP spearheaded the 1988 formation of the United Front Against Fascism, which played a decisive role in denying the white supremacists the traction they sought.

Each party branch continues to take on the fascist right, with our most recent work focusing against the anti-immigrant Minutemen. Also continuing into the present is abortion clinic defense, often initiated by our sister organization, Radical Women (RW).

But the party was not just in a reactive posture during the era of Reagan and Bush the First.

While new branches in the U.S. were putting down roots, pioneers in Australia made revolutionary feminism an international presence with the founding of FSP and RW branches there in 1983. The next year saw the debut of a new periodical, the Australian Freedom Socialist Bulletin. FSP in Australia has gone on to be highly active in the Aboriginal justice and union movements, anti-Nazi organizing, reproductive rights work in concert with RW, and political exchanges with other feminists and radicals in Asia.

Comrades in both Australia and the U.S. have run for office. The FSP has no illusions about changing the system through the ballot box. But elections are one of the best arenas to reach wide numbers of people and popularize socialist ideas, and we've done just that through energetic campaigns in Australia's state of Victoria, New York, California, Oregon, and Washington, as part of left slates or alliances when we can.

Fall of the Soviet Union impacts socialists internationally. As the FSP and other socialists in capitalist countries sought to hang on and make headway during the inhospitable '80s, world events took a dramatic turn with the rise of the union Solidarnosc in Poland.

As pro-democracy revolt spread to the other workers states of the Soviet bloc and the USSR itself, it raised the possibility of a political revolution against Stalinism that would toss out the hated bureaucracy while maintaining collective norms and structures. In other words, a profound shakeup that would restore not capitalism but the socialist direction subverted by pulverizing capitalist hostility and by Stalinism.

This would be a profound advance for all the world's workers, and the party threw itself into studying developments, writing about them, and intervening directly as we were able. Party representative Doug Barnes traveled to the USSR in 1988 to investigate perestroika and glasnost firsthand and give away writings by Trotsky in English and Russian.

Barnes found plenty of grass-roots approval for the socialized nature of the economy that provided jobs, housing, healthcare and education for all. But, to prevent the crumbling of Stalinism from turning into the comeback of capitalism, organized and consciously socialist leadership would have been required — and this proved to be lacking.

The fall of the Soviet bloc workers states, as corrupted as they were, was still a tragedy for workers worldwide. It resubmitted the people of these countries to the untender mercies of the profit system and removed the Stalinist brake, even if an unreliable one, on imperialist aggression around the globe.

At the same time, it provided new openings for talking about Trotskyism. Unfortunately, amid all the capitalist chest-thumping about the "death of communism," many Trotskyists internationally fell victim to demoralization right along with Communist Party members and sympathizers. This was true of the Fourth International (United Secretariat), which essentially closed shop as a Trotskyist and Leninist organization during this period, becoming a loose association of revolutionaries and reformists.

It was also true for a small number of FSPers who left the organization at this juncture. They included three leading members of the San Francisco Bay Area branch, who covered their retreat by picking a nasty, unprincipled fight with national party leadership and their own local members. But the comrades they deserted (in the middle of Merle Woo's campaign for California governor), most of them of color, were more than happy to say good riddance, and ably took up the branch reins.

New priorities in a changed world scene.With the demise of the USSR, Cuba suddenly became much more isolated and vulnerable, and FSP intensified its work in the island's defense. In our press and in personal dialog with representatives of the Cuban CP and the Federation of Cuban Women both in the U.S. and during repeated visits to Cuba, we urged these leaders to reexamine the distorting influence of Stalinism on Cuba's political development. We saw an opportunity for Cuba to revitalize the world socialist movement by heading up a regroupment of revolutionary forces internationally.

This regeneration was desperately needed (and remains so), since the U.S., after becoming the world's sole superpower, immediately escalated its use of military and economic might to shore up the still flagging global capitalist economy.

And it imposed neoliberal policies to fortify its economic position across the globe. As Guerry Hoddersen describes in One Hemisphere Indivisible: Permanent Revolution and Neoliberalism in the Americas, "Knocking down protective tariffs, deregulating banking and industry, ... privatizing natural resources and public industries, and destroying labor and environmental protections were all part of the new ballgame."

This onslaught sparked a worldwide movement against corporate globalization famously identified with the 1999 "Battle in Seattle" against the World Trade Organization, of which FSP was very much a part. Even so, in analyzing events afterward, we believed we could have better recognized the significance of what was happening as it unfolded and participated more strongly.

Our critique of that involvement produced a lightning response to 9/11 two years later. We rushed out a special edition of the FS, immediately opposed the invasions of Afghanistan and later Iraq, and began organizing against the phony, anti-immigrant "war on terror" as it unspooled domestically in both the U.S. and Australia.

Toward the future. In 1995 and 1998, respectively, veteran FSP leader Gloria Martin and founder Clara Fraser died, sad milestones for the party and for Radical Women.

Sexists on the Left, for whom the joint leadership of male and female feminists is a thing that passeth all understanding and who were fond of the myth of the party as "Clara's cult," predicted FSP's imminent demise. A decade later and still going strong, we are happy to have proved them wrong.

We established Red Letter Press in 1990, launched www.socialism.com in 1998, and increased publication of the FS to six times a year in 2004. In 2000, the growing Comrades of Color Caucus of RW and the party held a highly educational fourth national plenum that covered topics including immigration, the prison-industrial complex, and the relationship between racism and anti-Semitism.

Today, in the midst of exhilarating upheaval against imperialism in Latin America, FSP has dived into study about Latin American issues and is working to develop connections with revolutionaries there, especially other Trotskyists. These are give-and-take relationships in which we are finding pronounced interest in our socialist feminist program and practice and are deepening our own political understanding.

The FSP strives to integrate the lessons of Marxist history with an interventionist, creative approach to the present. Our staying power lies in a dialectical approach that aids in analyzing the contradictory real world, feminist dedication to the most oppressed, and optimism about the power of our class. We have confidence that our next years will be ones of growth both for the party and for the prospects for international socialist revolution.

Every day, people depend on the open internet for education, employment, health care, civic power and so much more — in spite of institutional barriers like racism, homophobia, gender discrimination and poverty. Let FCC Chairman Ajit Pai know that destroying Net Neutrality would actually destroy lives.

San Francisco

Mondays, 7p - 8:30pm / Wednesdays, 3p – 4:30p

The History of American Trotskyism Study Group

Los Angeles

Mon, September 25, 7-9pm

Join Movement Mondays at Solidarity Hall

New York City

Ongoing

Campaign for an Elected Civilian Review Board meetings

Seattle

Sunday, September 17th, 2pm

Marxism in the 21st century

Mondays, Aug. 14 thru Sept. 29 (excluding Labor Day weekend), 7:00-8:30pm

Six-week discussion circle on the book Poor Workers' Unions

Melbourne

Sun, 17 September

Protest with Freedom Socialist Party against racist police powers!

Wed 4 October, 6.30 pm

4-session study circle: Lessons of October: Learning from the 1917 Russian Revolution

Wed 8 November, 6:30 pm

8-session study circle: Democracy and Revolution