Hours before I met Ben Passmore for the first time, I’d been informed that it was the first night of Mardis Gras in New Orleans. My partner and I were on tour in the American South and had not made any definitive plans for the space on the map between Atlanta and Houston. A friend of a friend put us in touch, and we gathered in a small group waiting for the Krewe du Vieux parade to start. The night’s theme: “politically incorrect”.

I could hear wooden chips and beads crunching under my shoes as I struggled to distribute the seven jell-o shots I’d just purchased from a nice old lady pushing a cooler through the crowd along the sidewalk. We stood, drinking, smoking, and watched the floats pass: a pair of queens with enormous falsies, an old white man from the ‘NOLA for Bernie Sanders campaign’ wearing a fake indigenous headdress and throwing candy. It was somewhat surreal, somewhat entirely foreseeable.

Mardis Gras continues like clockwork every year, but a lot of New Orleans has changed since Hurricane Katrina. The largest residential building in the city is abandoned. Entire neighbourhoods are boarded up, next to other neighborhoods peppered with colourful and chic low-income housing built with donations from celebrities like Brad Pitt and Sean Penn. In many ways, post-Katrina NOLA became the poster city for explaining concepts like disaster capitalism, neo-liberalism, and gentrification.

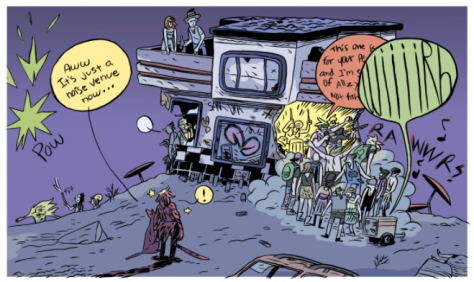

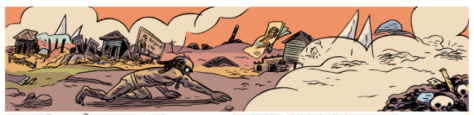

It’s hard not to notice elements of this un-done landscape in Passmore’s online comic, D A Y G L O A H O L E, which he worked on for years while living in the city. Characters wander around a mysterious post-civilization wasteland. There are semi-familiar objects everywhere, but ‘civil society’ and all that phrase entails is gone. Washed away. Each new comic extends further into this post-apocalyptic future, and deeper into Passmore’s mind we go.

“Daygloayhole has consistently been too ambitious for my level of talent, but I think that’s what makes it fun. I’m not a huge sci-fi nerd, but what little of it I’ve consumed and enjoyed consistently pairs the recognizable with the fantastically alien.”

Passmore spent several years working on daygloahole, living in New Orleans. Life was a mix of work, going to shows, and fostering a burgeoning indie comics scene through the NOLA zine and comics fair. Of course a city known for its history of parades and grassroots activism will attract its share of artists, hippies, road punks, and anarchists. When I suggested that New Orleans appeared to solve the age-old mystery of where crust punks go to die, he said it was “more to become undead… There’s a lot of lumbering soulessness [here].”

And the anarchists were having a moment. Abandoned buildings were being squatted and used for political organizing or art projects.

The phrase ‘It’s all over’ appears again and again in daygloahole, which was funny because that’s all I could think when I was in New Orleans. And then, it doesn’t seem quite as funny anymore.

“I think that’s something that I enjoyed at first, the culture of collapse in New Orleans, until I really realized the toll Katrina took on people’s minds and lives, and the disparity it underlined.”

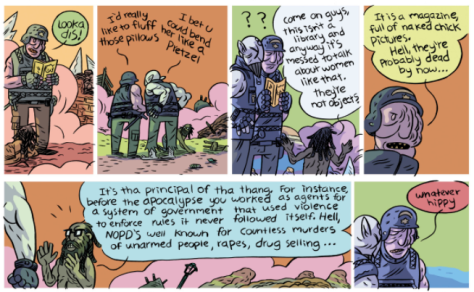

That disparity is one drawn clearly around race in New Orleans and Louisiana as a whole, whether we’re talking about segregation of schools and neighborhoods, police violence, or the state prison system. It was only in the last year that New Orleans removed several Confederate Monuments, which Passmore documented for the comics journalism website, The Nib.

The Confederate Monument fights became a flashpoint in the South for confronting fascist and white supremacist forces, who were being emboldened by Trump’s campaign to “Make America Great Again” (a perfect dog-whistle for the South’s “Lost Cause” sentiment, which sticks around like 100% humidity). From inside a jail cell for confronting the KKK at Stone Mountain, to the streets of New Orleans where a masked Mardis Gras parade took to a Confederate statue with paint and sledgehammers, Ben took names, covered it, drew it, and showed the rest of us what was going on.

-

“I’ve been really excited about doing pieces for the NIB,” Ben says. “It’s good to have to explain your ideas with pictures and words if you’re politically wing-nutty. I assume the majority of the NIB readership is liberal and prolly not very into most of my Anarchist politics.”

“New Orleans created a feeling of urgency about white supremacy as a societal poison that I didn’t feel as much before I moved there.”

“And it for sure burned me out on white people.”

In 2017, Ben Passmore made international news for having his work, a short 16-page comic called “Your Black Friend,” nominated for an Eisner Award. For those of you not in the comics industry: that’s kind of like being nominated for an Academy Award. Needless to say, as an anarchist, but more as a political comic enthusiast, I was pretty stoked about the news.

‘Your Black Friend’ is a comic for that person who wants you to know they’re not a racist. It’s a comic about micro-aggressions, cultural appropriation, and lefty-progressive virtue-signalling. It is a short but poetically full-circle sampling of how annoying, depressing, terrifying, and frustrating it is to share space and community with white people (even those nice ones) in a white supremacist world.

Passmore’s first 20 years were in and around Great Barrington, Massachusetts. “My mom was/is an artist and she encouraged me to draw a lot. I think she would’ve liked me to draw trees… I drew a lot of muscle guys in spandex covered in spikes.”

Ben would eventually go on to art school and major in comics with a minor in illustration.

Passmore seems somewhat surprised that younger people are inspired by his work.

“I get messages from other weird black cartoonists and people that get stuff out of my comics. A couple times people have told me that they’ve been “reading my comics for years” and they’re in their early twenties which is such a crazy thing to be a part of someone’s cultural scenery when they’re turning into an adult.”

There’s a lot being processed in Passmore’s comics, from the low-key racism of his friends, to his Mom voting for Trump, to his own relationships with addiction, depression and impulses to self-harm. Ben has made space for it all, while never taking himself too seriously.

A current project of Passmore’s –not yet released– deals with identity, inspired by the pronounced dysphoria he experienced during the last two years’ living in NOLA. I’m looking forward to seeing that, given the nuance he gives to subjects like blackness and queerness. “I’ve never subscribed to the ‘destroy everything/destroy my body’ that characterizes some queer nihilism. Not because I don’t think that strain has validity, it’s just it feels complicated to be black and to desire physical deconstruction.”

Leftist comics – much like “the Left” in general– have a tendency to forget the nuance in their attempt to promote a cause. And that’s a fine strategy, if you’re designing lawn signs for an election.

Passmore’s work shows us that a comic is capable of something infinitely more sophisticated.

His advice to folks who want to make political comics: “Don’t be preachy… if peeps don’t at least recognize your point of view, it’s cause you didn’t make your case well enough.”

‘Your Black Friend‘ is available now from Silver Sprocket. Follow Ben’s adventures on Twitter and Tumblr, and if you want to show Ben some support, throw some pocket change at his patreon page.

The backdrop of this period was one where political and economic opponents would use the fledgling structures of ‘law and order’ and the ignorance of a population as the stage for their power plays. The book opens with a compelling example, pre-trials: the burning of the Knights Templar in 1314. King Philip the IV of France owed this wealthy organization a great deal of money, but had successfully condemned them to the stake with charges nearly impossible to prove: idolatry, heresy, and sorcery. In Jews, Muslims, pagans, and even uncooperative Christians, men of courts and men with connections found infinite ways to scapegoat these “others” in dark and difficult times.

The backdrop of this period was one where political and economic opponents would use the fledgling structures of ‘law and order’ and the ignorance of a population as the stage for their power plays. The book opens with a compelling example, pre-trials: the burning of the Knights Templar in 1314. King Philip the IV of France owed this wealthy organization a great deal of money, but had successfully condemned them to the stake with charges nearly impossible to prove: idolatry, heresy, and sorcery. In Jews, Muslims, pagans, and even uncooperative Christians, men of courts and men with connections found infinite ways to scapegoat these “others” in dark and difficult times.

But ignorance can take on a life of its own, in time. As the book explains, the Catholic Church outright denied the existence of witchcraft for some time. This required Witch Hunters to make their accusations and arguments on grounds of heresy, or demon worship. Still, belief in witchcraft spread until the Church and its adherents took a more committed position. This was manifested in the works of Heinrich Kramer, a witch hunter and the author of Malleus Malificarum, or “The Witch’s Hammer”.

But ignorance can take on a life of its own, in time. As the book explains, the Catholic Church outright denied the existence of witchcraft for some time. This required Witch Hunters to make their accusations and arguments on grounds of heresy, or demon worship. Still, belief in witchcraft spread until the Church and its adherents took a more committed position. This was manifested in the works of Heinrich Kramer, a witch hunter and the author of Malleus Malificarum, or “The Witch’s Hammer”.

Peter Kuper’s new graphic novel, ‘Ruins’, is a breakthrough, even though this veteran cartoonist has been publishing books since 1980, producing more titles than I can count.

Peter Kuper’s new graphic novel, ‘Ruins’, is a breakthrough, even though this veteran cartoonist has been publishing books since 1980, producing more titles than I can count.