Marxism & Anarchism

Resources on the theory and practice of anarchism and the unity and conflict between Marxists and Anarchists over the past 150 years.

See Anarchism

in M.I.A. Encyclopedia.

Beginnings

The founders of both Anarchism and Marxism all came out of the dissolution of the Young Hegelians in the 1840s, during the revolutionary upheavals that swept across Europe and destroyed the “Old Order”. Both Mikhail Bakunin and Frederick Engels were present at the December 1841 lecture by Friedrich Schelling denouncing Hegel, representing two of the plethora of radical currents that sprung out of that conjuncture. Also with their roots in the Young Hegelians were Max Stirner, a founder of libertarian individualism, one of the targets of Marx’s The Holy Family, Proudhon, the founder of theoretical anarchism and Bakunin’s teacher.

Louis-Auguste Blanqui (1805-1881)

The writings of Blanqui are currently being made available in English for the first time in the M.I.A. Reference Archive. Despite spending most of his adult life in French prisons, Blanqui was a hero of the French working class and was elected President of the Paris Commune in 1871. The government refused to allow Blanqui to take up his position.

Blanqui is more a communist rather than an anarchist and yet he is a precursor of both. His policy was for the formation of secret armed detachments of workers for the purpose of seizing political power, smashing the forces of the bourgeoisie and implementing socialism. His long years in jail were the result of his repeated attempts to put theory into practice.

His heroism, honesty and charisma earned him the respect of Marx and Proudhon alike, and Mikhail Bakunin was a supporter of Blanqui in his early years. Blanqui is the forerunner of the “urban guerillas” of the 1960s as well as the “militant” anarchists in the anti-WTO movement.

From the 1860s onwards, Anarchists and Communists alike rejected Blanqui’s “conspiratorial” strategy, though ironically it has forever after remained the bourgeoisie’s stereotype of radicalism.

Blanqui Archive,

Biography of Blanqui.

–– The pioneers of Anarchism ––

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1803-1865)

“Property is not self-existent. An extraneous cause – either force or fraud – is necessary to its life ... it is a negation, a delusion, nothing.”

Proudhon was the first the attempt to use Hegelian ideas to make a radical critique of political economy. This work is first set out in What is Property? (1840) but his most famous work is The Philosophy of Poverty (1847), the subject of Marx’s famous Poverty of Philosophy. Proudhon’s ideas were probably the most influential current among the participants in the Paris Commune of 1871. Proudhon’s ideas are at the root of that type of anarchism which envisages a world of small-scale producers living in self-sufficient, sustainable communities using local systems of exchange. It is often called “petit-bourgeois anarchism” because its ideal is the self-sufficient independent proprietor, and appeals to the self-employed tadesperson or small business person in capitalist society whose hatred is directed against big capital.

Proudhon Archive,

Marx on Anarchism,

Brief Biography of Proudhon.

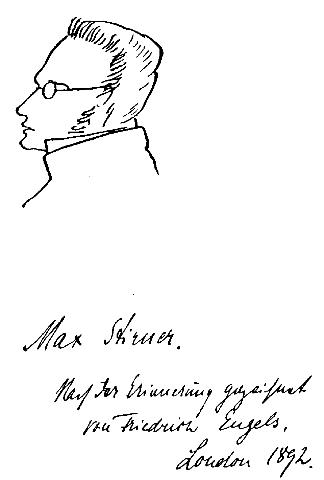

Max Stirner (1806-1856)

“Communism rightly revolts against the pressure that I experience from individual proprietors; but still more horrible is the might that it puts in the hands of the collectivity.”

Max Stirner was one of the Young Hegelians blasted by Marx as “Saint Max” in Chapter 3 of The German Ideology (1845).

We do not have any works by Max Stirner on M.I.A. at the moment, but Stirner’s major work, The Ego and Its Own, and other works are available from The Egoist Archive.

See Stirner and Nietzsche, by Albert Lévy, 1904

Stirner was also a Young Hegelian, but returned to the philosophy of Hegel’s predecessor, Johann Fichte. Stirner advocates egoism, an extreme form of Libertarianism which idolises individualism and rejects any and all forms of collectivism. Thus, in contrast to the communal spirit of Proudhon’s philosophy, Stirner is the precursor of Autonomism. Shades of Stirner are also visible in Nietzsche.

Edgar Bauer (1820-1886)

Biography

The Political Revolution, 1842

Mikhail Bakunin (1814-1876)

“A popular insurrection, by its very nature, is instinctive, chaotic, and destructive, and always entails great personal sacrifice ... The masses are always ready to sacrifice themselves; and this is what turns them into a brutal and savage horde, capable of performing heroic and apparently impossible exploits”

Mikhail Bakunin, a Russian aristocrat and archetypal revolutionary firebrand, is the most famous and important of 19th century anarchists. Bakunin was also a Young Hegelian, who turned Hegel’s conception of the State as “the march of God on Earth” on its head, casting the state as the representative of evil. (See God and the State)

Initially an advocate of “Democratic Pan-Slavism” (See Appeal to the Slavs, Bakunin 1848, and Democratic Pan-Slavism Neue Rheinische Zeitung, February 1849) and a member of the Narodniks, who advocated terror as a weapon against the Czarist autocracy in pursuit of a type of communism founded on the Russian village commune. (See Marx on the Russian Revolution.)

Bakunin was won over to socialism by the influence of Blanqui, and Bakunin was notorious for his propensity to form secret organisations fomenting rebellion. Bakunin regarded Proudhon however as his foremost teacher and recognised Proudhon as the founder of anarchism.

In 1866, Bakunin joined the International Workingmen’s Association and built up an anarchist wing within the International, along with James Guillaume, Errico Malatesta and others. After the defeat of the Paris Commune in 1871, a reaction set in in Europe. Bakunin was expelled from the International at the Hague Congress in 1872, and his influence declined after this time and he died in 1876.

Mikhail Bakunin Archive

Brief Biography of Bakunin

Mikhail Bakunin. A Biographical Sketch by James Guillaume

The Conflict with Bakunin

Marx & Engels’ Writings on Bakunin.

James Guillaume (1844-1916)

“The communes will freely unite and organize themselves in accordance with their economic interests, their language affinities, and their geographic circumstances”

Guillaume was Bakunin’s closest comrade, a member of the International Workingmen’s Association, the main chronicler of Bakunin’s life and work and later also a founder of the Anarcho-Syndicalist movement in the early 20th century.

See his Ideas on Social Organisation (1876) for a summary of the ideas of the nineteenth century anarchist movement.

And see The Necessity and Bases for an Accord, a response to the rise of mass programmatic socialism aspiring to state power, on one side and the terminal insanity of “bomb-throwing” anarchism on the other, by Saverio Merlino, 1892.

See also, the Italian Anarchist: Errico Malatesta, (1853-1932), a member of the First International from 1871.

Among the Russian Anarchists, see Peter Kropotkin (1842-1921), the Anarchist-terrorist, Sergey Nechayev (1847-1882), author of the Revolutionary Catechism.

Ravachol (1859-1892)

Ravachol and Emile Henry were among the “bomb-throwing anarchists” of pre-World War I France, alluded to, for example, in Emile Zola’s Germinale and in Victor Serge’s memoirs.

“I am nothing but an uneducated worker; but because I have lived the life of the poor, I feel more than a rich bourgeois the iniquity of your repressive laws. What gives you the right to kill or lock up a man who, put on earth with the need to live, found himself obliged to take that which he lacks in order to feed himself?” [Ravachol Archive]

See also Archives of Octave Mirbeau (1848-1917), Léo Taxil (1854-1907), Sebastien Faure (1858-1942), Emile Pouget (1860-1931), Fernando Tarrida del Marmol (1862-1915), Georges Darien (1862-1921), Zo d’Axa (1864-1930), Georges Etiévant (1865-), Emile Armand (1872-1963), Manuel Devaldes (1875-1956), Emile Henry (1872-1894), Libertad (1875-1908), Marius Jacob (1879-1954), Elisée Reclus (1830-1905), Paraf-Javal, Jules Méline and Andre Lorulot (1885-1963), Noël Demeure (1906), The Bandit of the North (1890), Louis-Ferdinand Céline (1894-1961) and Letter from a Conscript.

Anarchy and Comunism, Carlos Cafiero 1880.

See On the Anarchists, Jean Jaurès 1894.

Is the Anarchist Ideal Realizable?, La Revue Anarchiste, Dec 1929, Jan & Feb 1930.

Excerpts from “The Anarchist Encyclopedia,” ed. Sébastien Faure 1934.

The Sacred Conspiracy, Georges Bataille 1936.

Anarchy and its Heroes, Cesare Lombroso 1897.

Manifesto of the Anti-parliamentary Committee, Paris 1910.

Anarchists have also contributed to the development of philosophy in the 20th century. See the Georges Palante Archive, for example.

–– From the History Archives ––

Both communism and anarchism, as revolutionary currents in the working class, have their origins in the struggles of the working class itself, not just in the writings of its leaders. The following episodes of revolutionary struggle are crucial to understanding the origins of both communism and anarchism.

The English Revolution

The English Revolution of 1640-48, in which Oliver Cromwell built the New Model Army, decapitated Charles II and laid the basis for the constitutional monarchy under which the bourgeoisie could develop its industry and trade without the fetters of feudalism

The English Revolution was also the scene of revolutionary struggles by the predecessors of the modern revolutionaries: the Diggers and the Levellers.

The English Revolution, by Christopher Hill

True Levellers Standard Advanced, by Gerrard Winstanley (1649).

“In the beginning of Time, the great Creator Reason, made the Earth to be a Common Treasury, ... but not one word was spoken in the beginning, That one branch of mankind should rule over another”

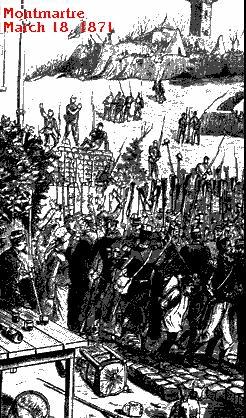

The Paris Commune

In 1871, with Paris surrounded by Prussian troops after France had capitulated, the workers of Paris rose up and seized power. This was the first time in history that the working class had seized state power. The ideas of Proudhon and Blanqui were the most widespread theories of revolution known to the Paris workers, but the International Workingmen’s Association actively participated through its Parisian section. The Commune was eventually overthrown by a reactionary army raised in the countryside and workers were slaughtered. Blanqui was elected President of the Paris Commune, but remained in prison throughout.

The Paris Commune was the testing ground for revolutionary theory, and in the light of its experiences Marx revised his theory of the State, concluding that the working class had to smash the state machine, rather than hoping to take it over or leaving it intact.

Paris Commune History Archive, including

The Paris Commune of 1871 by Henri Lissagaray and

The Civil War in France by Karl Marx.

Syndicalism

During the last decades of the 19th century the socialist movement progressed well while anarchism became marginalised and generally reduced to terrorism and sabotage. However, while tranforming itself into vast working-class parties, the socialist movement also became somewhat “respectable”. The conflict between Rosa Luxemburg and Eduard Bernstein and between Lenin and Kautsky illustrate the divergence between reformist and revolutionary wings of socialism. Doctrinaire socialists such as Henry Hyndman also criticised the mass socialist parties from the left.

At the same time, a dynamic new movement grew in the working class, particularly in the trade unions, which merged features of Marxist theory with the best traditions of anarchism. This current became known as Anarcho-Syndicalism. Participants in this movement included both anarchists and Marxists, and others somewhere in between.

Anarcho-syndicalism was especially strong in the English-speaking world where the trade union movement had its own traditions independently of the political parties and in Spain and Italy, where anarchism had a long history among the peasantry before the advent of anarchist theory in the workers’ movement.

The founders of Anarcho-Syndicalism in the English-speaking world were socialists before they were anarchists, and looked to Marx not Bakunin for their theory. However, their focus on the independent development of the trade unions and their suspicion of parliamentarians provided the stimulus for the development of the vibrant and anarchic Industrial Workers of the World.

Rudolf Rocker (1873-1958)

“In modern Anarchism we have the confluence of the two great currents which before and since the French Revolution have found such characteristic expression in the intellectual life of Europe: Socialism and Liberalism.”

Rudolf Rocker, a German immigrant to the U.S., is generally regarded as the founder of syndicalism, the doctrine which emphasises the role of the trade unions as vehicles of working class power and rejects the use of party-political organisation. His history of anarchism and anarcho-syndicalism is an excellent resource for the anarchism of the early 20th century.

¤ Anarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalism, Rudolf Rocker

Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)

The IWW was a powerful movement that engaged both socialists and anarchists in the early years of the 20th century, especially in the English-speaking world. Among Marxists who fought against Anarchism and Syndicalism within the unions were Eugene Debs and Daniel DeLeon.

Daniel De Leon (1852-1914)

Founder of the US Socialist Labor Party and advocated “socialist industrial unionism.”

“Working Class still is a tumultuous mob. No revolutionary class is ever ripe for success before it has itself well in hand. ... It is one of the missions of the Trades Union to drill its class into the discipline that civilization demands.”

De Leon Archive

Biography of Daniel De Leon by Mike Lepore

Eugene V. Debs (1855-1926)

American socialist, co-founder of the IWW and a leader of the left-wing of the Socialist Party. Solidarised with the Russian Revolution, but did not join the Communist Party.

“The workers ... are developing their industrial consciousness, their economic and political power; and when the revolution comes, they will be prepared to take possession and assume control of every industry. With the education they will have received in the Industrial Workers they will be drilled and disciplined, trained and fitted for Industrial Mastery and Social Freedom.”

Debs Archive,

Brief Biography Eugene V Debs.

Among the Marxists who fought against the syndicalist anti-party disposition of the workers, and in favour of the formation of a socialist party, in the early 20th century was John Maclean. Maclean argued for a single revolutionary socialist party and was made Soviet Consul in Scotland after the October Revolution.

After the Russian Revolution, the Communist International recognised the I.W.W. as the representative of the most militant sections of the working class in the English-speaking world, and made a decisive effort to enlist the I.W.W. in its ranks. Many of its leaders, such as Eugene Debs, Big Bill Haywood and Jock Garden joined the Communist International and were instrumental in founding the Communist Party in their own country. There was another wave of IWW recruits to the Comintern during Stalin’s "Third Period" in the late 1920s.

England: When the Anarchist International held their Congress in London in 1881, the four English delegates who attended were not actually anarchists and listened in silence. Until the 1960s, anarchism, in the forms known on the Contintent, never took on in England; the English anarchists were either anarcho-syndicalists or better described as ultra-left or anti-parliamentarian socialists. The Social Democratic Federation split between pro- and anti-parliamentary groupings, and Joseph Lane was an archetype of the English anti-parliamentary socialist agitator, and people like William Morris, Frantz Kitz and Sam Mainwaring were sympathetic to his position.

Later on, people like Sylvia Pankhurst and Kate Sharpley, supported the Russian Revolution, but rejected participation in Parliament.

See also the Communist Left Subject Archive.

Unfortunately we do not currently have material on the Spanish and Italian anarchist movements of this period. These movements were more directly connected with Bakunin’s supporters from the 1860s, and James Guillaume was also an active player in laying the theoretical foundations of anarcho-syndicalism and introducing the experiences and traditions of Bakunin’s work to a new generation of anarchists. The Anarchist History Archive [external link] says of the Italian anarchist movement:

“In 1906, the Confederazione Generale di Lavoro (CGL) was formed to centralize and control the local Chambers of Labor. Six years later, in 1912, the Unione Sindacale Italiana (USI) broke away espousing anarchist-inspired syndicalism. By 1919, it was fairly sizeable though dispersed through multiple regions. Despite attempts at worker control and self-governing, World War I and the more reformist CGL prevented the USI from every really consolidating its strength. In the early 1920’s fascism came along and it saw to anarchism’s decline.

Anarchism and the Russian Revolution

Anarchism has a long history in Russia dating back to Bakunin and peasant struggles against the Czarist autocracy and the landowners.

–– From the History Archives ––

The Russian Revolution

Particularly during the Civil War, after the Russian Revolution of 1917, substantial anarchist movements grew up, and found bases of support both in the Russian working class and particularly amongst national groups fighting for their independence.

¤ Russian Revolution History Archive

¤ History of Anarchism in Russia, from the Anarchist History Archives [external link]

Strangely enough, it was Mikhail Bakunin who can be credited with introducing Marxism into Russia. Through Narodnya Volya (People’s Will) he recruited Georgi Plekhanov, widely recognised as the "father of Russian Marxism", teacher of Lenin and Trotsky. The Narodniks advocated secret society terrorist methods of struggle reminiscent of Louis-Auguste Blanqui.

Although the Narodniks pre-existed Bakunin, his supporters would become its main force. Later, Bakunin’s supporter, James Guillaume, recruited the Russian emigré Prince Petr Kropotkin (1842-1921) to anarchism. (Anarchism of the libertarian variety has a long history of support in the Russian aristocracy, counting Leo Tolstoy among its numbers.) Kropotkin was the most prominent anarchist of the years leading up to the Revolution, but he is not a significant figure for the anarchism of the post-revolutionary period.

Makhno Nestor (1884-1934), a leader of the anarchist armies which fought against both the Red Army and the invading White Armies, is probably the most famous of Russian anarchists of the time of the Civil War.

Victor Serge, an anarchist who was deported to Russia by France in 1918, became Assistant Secretary of the Communist International under Zinoviev and made great efforts to reconcile the anarchists and the Bolsheviks until the rise of Stalin made such a project impossible. Serge was the last member of the Left Opposition to leave the Soviet Union before the Moscow Trials led to the execution of all Stalin’s opponents.

¤ The First of May, Nestor Makhno, 1928

¤ Victor Serge Home Page [external link]

¤ Volin (1882-1945) served under Makhno, later lived in Berlin and then Paris where he collaborated with Sébastien Faure.

Emma Goldman (1864-1940)

One of the most important anarchists of post-revolutionary Russia was Emma Goldman, whose political life spanned the I.W.W. activities and the anti-conscription fight in the U.S., Soviet Russia and the Spanish Civil War, in whose cause Emma Goldman gave her life.

William Morris:

Socialism and Anarchism, 1889.

Plekhanov:

Anarchism and Socialism, 1895.

See also Fredy Perlman Archive.

Bolshevik Writings on Anarchism

Leon Trotsky

My First Exile, My Life

Why Marxists oppose Individual Terrorism, 1909

The July Days, History of the Russian Revolution

The Makhno Movement, 1919

Makhno’s Coming Over to the Side of the Soviets, 1920

How Is Makhno’s Troop Organised?, 1920

Contradictions Between the Economic Successes of the Ussr and the Bureaucratization of the Regime, 1932

Lenin

Anarchism and Socialism, 1901

Guerilla Warfare, 1906

Socialism and War, 1914

State & Revolution. Controversy with the Anarchists, 1917

Anarchism and the Spanish Civil War

A democratic republic was formed in Spain in 1936, but Franco assembled a Fascist Army in Morrocco and with the aid of Mussolini and Hitler, waged a civil war which overthrew the republic and established a fascist dictatorship.

Workers came from all over the world to fight alongside the Republicans in the International Brigades. However, following the triumph of fascism in Germany, Stalin and the Spanish Communist Party were more interested in avoiding revolution in Spain than in defeating fascism, so as to appease “democratic imperialism”. As a result, the Soviet Union used its forces to split the revolution, and Franco faced Stalinists, Trotskyists, “Centrists” and Anarchists who were unable to form a United Front.

–– From the History Archives ––

Anarchism had a long history in Spain, going back to the 1830s, with a strong syndicalist movement among the workers. The main anarchist force in Spain was the C.N.T. (National Confederation of Workers).

¤ Images of Anarchists in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939)

Sydney Libertarianism

Sydney Libertarianism was one example of anarchistic and libertarian currents found in urban centres around the world. See Documents from this current.

Atheism

Socialism and Religion, F A Ridley

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Some American Anarchist Writers and Documents

A Word to Tramps, by Lucy E. Parsons [Oct. 4, 1884] Article by Lucy E. Parsons, wife of future Haymarket Affair victim Albert Parsons and herself a committed anarchist, from the front page of the premiere issue of The Alarm. Parsons addresses herself to the 30,000 unemployed of Chicago and implores them to ascertain the reason for their hunger, ragged clothing and distress. “Can you not see that it is the industrial system and not the ’boss’ which must be changed?” Parsons asks. The rich with their palatial dwellings are the cause of this despoilment, Parsons notes, people who have “never yet deigned to notice any petition from their slaves that they were not compelled to read by the red glare bursting from the cannons’ mouths, or that was not handed to them upon the point of the sword.” No organization is needed to deliver a message to these “robbers,” Parson indicates. She urges her readers to “avail yourselves of those little methods of warfare which Science has placed in the hands of the poor man, and you will become a power in this or any other land. Learn the use of explosives!”

Equal Rights, by Albert Parsons [Nov. 15, 1884] This editorial from The Alarm notes that the path to wealth and leisure is a chimera, attainable by not one person in ten, of whom not one in ten is capable of maintaining the status. The only way to achieve this, in Parsons’ view, is by standing on those beneath them in the role of exploiter. “Suppose some of those underneath concluded to use a little dynamite to blow off their burdens, might it not be possible that some of these ambitious ones on top would then conceive of some safer way to gratify their ambitions without taking a fellow creature for a footstool to climb up with?” Parsons rhetorically asks. “Gunpowder brought the world some liberty and dynamite will bring the world as much more as it is stronger than gunpowder. No man has a right to boost himself by even treading on another’s toes. Dynamite will produce equality.”

Force! The Only Defense Against Injustice and Oppression, by C.S. Griffin [Jan. 13, 1885] Leading Chicago English-language anarchist spokesman C.S. Griffin offers this short defense of the use of violence in the social revolution. Griffin proclaims the “ vigorous use of dynamite” to be both “ humane and economical.” “ It is clearly more humane to blow ten men into eternity than to make ten men starve to death,” Griffin declares, adding that “ When ten men unite to starve one man to death, then it is humane and just to blow up the whole ten men.” Griffin asserts that “ A system that is starving and freezing tens of thousands of little children, right in the midst of a world of plenty, cannot be defended against dynamiters on the ground of humanity.” He adds that “ If every child that starves to death in the United States was retaliated for by the execution of a rich man in his own parlor, the brutal system of wage-property would not last six weeks.” “ The privileged class use force to perpetuate their power, and the despoiled workers must use force to prevent it,” Griffin says.

The Black Flag! The Emblem of Hunger Unfurled by the Proletarians of Chicago [event of Nov. 27, 1884] Lengthy and detailed first-hand journalistic account of the march of 3,000 “Social Revolutionists” (Anarchists) through the streets of Chicago, published in The Alarm. The Social Revolutionists made use of the Thanksgiving holiday as an organizing device to protest the unemployment and poverty held to be an intrinsic part of the current social and economic system. Included is the full text of the organizing leaflet, produced by a self-described “Committee of the Grateful” of the anarchist International Working People’s Association, as well as excerpts of the speeches of Albert R. Parsons, C.S. Griffin, and Samuel Fielding, banner slogans, and resolutions adopted by acclamation by the demonstration’s participants. According to leading participant August Spies, this demonstration marked the first time that the black flag, the “emblem of hunger and starvation,” had been unfurled on American soil. The ecumenical nature of the Chicago Social Revolutionary movement at this juncture is reflected by the three cheers given for “our comrades the Anarchists of France and Austria, the Socialists of Germany, the Nihilists of Russia, and the Social Democrats of England.” A brief move by some to sack the mansion of Elihu Washburn, US Ambassador to France during the Paris Commune, was turned aside by calmer participants. Also included is an account from the Chicago Tribune describing the new anti-street riot tactics in which the National Guard was training in Chicago.

| |||

| |||||||||||||||

Purchase many of these writings in The Great Anger, by Mitch Abidor

Comments to Andy Blunden |

M.I.A. Home Page