While I’ve published over 430 Indexed experiential and political articles on this site, occasionally I also publish short-story fiction that I believe some will find of interest . . . and sometimes fiction rivals the truth. This is one of those stories. As a veteran of the 101st Airborne (1959-61) and founder of the Detroit Veterans against the War (’67), I’m proud to consider myself a Winter Warrior, not a Sunshine Patriot…

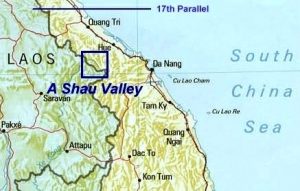

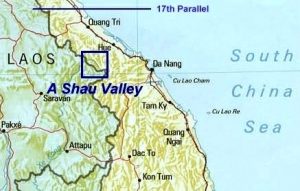

The two ‘troopers of the 101st Airborne were both 19-yrs-old, recently assigned to Vietnam, 1969. Their area of operations, the A Shau Valley in the center of the nation, was a notorious bastion of Vietnamese resistance. Every newbie learned boocoo-didimau the all-too-real story of the area–not the media mythology hyped back stateside to the American public.

The two ‘troopers of the 101st Airborne were both 19-yrs-old, recently assigned to Vietnam, 1969. Their area of operations, the A Shau Valley in the center of the nation, was a notorious bastion of Vietnamese resistance. Every newbie learned boocoo-didimau the all-too-real story of the area–not the media mythology hyped back stateside to the American public.

The Special Forces camp was overrun in ’66. The US subsequently learned in later battles there—and throughout Vietnam, for that matter–that the only land they were ever victorious over was the land they physically occupied . . . and then only for the time they occupied it.

Part of this reality was the result of Vietnamese Resistance forces fading into the countryside when major US forces deployed into an area. Subsequently, American frustration was often taken out on the remaining villagers and farmers . . . often, older women and children.

Dido and Christopher were on patrol searching for contact w/the enemy. Intel had all-but-assured them that there was no organized force in the area, but they did surprise a small family working a field. It turned out that their village had been totally destroyed in earlier B-52 carpet bombing. They were all that was left.

The A Shau Valley…

The American patrol was a small force of 14 men backed up by a South Vietnamese Army group of 10 more. Initially, several children ran off into the brush at the approach of the patrol. Several of the men, including Dido and Chris, were paired off to pursue and capture them.

Dido was never a happy ‘trooper. Wary of an ambush, he was cursing the LT a blue streak under his breath as they moved out. Chris ignored him. He was satisfied to not be a witness to the SVA “questioning” the women for information on their younger men and women who were no doubt Viet Cong irregulars off somewhere.

The men knew that the war was a lost cause. Nixon had been elected and the military was waiting for him to reveal his “secret plan” to wind down the conflict. No one wanted to be the last killed on a lost battlefield.

After moving further into the nearby forest and beating the bush, Chris heard a piercing scream and then muffled cries. Returning to Dido, he found his partner standing over a naked, bloodied young girl with his foot on her chest. She was gasping for air. Dido was pulling up his pants. Chris froze. Dido laughed and said, “No use letting it go to waste. Want sloppy seconds?”

Christopher said nothing. Dido shrugged and reaching down, he pulled a knife from his boot and slit her throat all in one fluid motion. Chris leveled his weapon and emptied his clip into Dido.

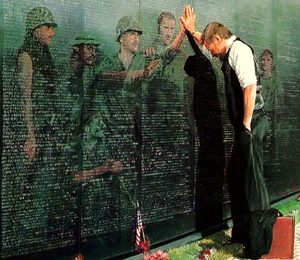

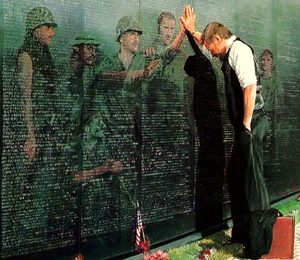

Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall…

When they found Dido’s body he became one of the 58,272 KIA on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, DC. A similar wall in Vietnam would have to contain up to three-million names . . . mostly civilians. Christopher was listed as MIA. They never found his body…

Jackie Ladino studied the photos of a tooth, fragment of jaw, and the forensic report that arrived from the Army’s lab in Hawaii. She knew that the likelihood of recovering more was practically nil.

The young woman next to her, Laura Strachan, also looked at the report, “Yes, this is the same one my mother received, minus the details regarding the source of its recovery. It says here that the remains were found by a ‘mushroom hunter’ in the A Shau Valley? Where’s that?”

“It’s up in the Central Highlands, in the north of South Vietnam. That’s where your grandfather was stationed during his tour,” said Jackie. “Your mother was unable to come?”

“Mom is bedridden . . . cancer. I’ve heard about Grandpa Chris all my life and promised her that I’d do everything I can to track down his final days and maybe even whatever remains there are for a decent funeral. He never had one. There wasn’t even a memorial,” Laura replied.

“I see here that he was only 19 when he went MIA. Your mother is his daughter?”

“Yes, she was born after he disappeared,” said Laura. “He and Grandma Phyllis were engaged and he never even knew that she was pregnant. She died young. Mom said it was from a broken heart. I think some answers, some closure, would help–.”

“Well, I can’t give you any guarantees, but our mission here in Vietnam has been quite successful and the Vietnamese have been remarkably cooperative,” said Jackie.

Ho Chi Minh City today…

Jackie Ladino filed the necessary paperwork w/the local gov’t office in Ho Chi Minh City, formerly known as Saigon to the French and later the American forces. With the official document, the Vietnamese gave both Jackie and Laura a military flight to the airbase at Hue, formerly the Imperial Capital of the Nguyen Dynasty back in the 1800s, the site of devastation by American forces after the Tet Offensive in ’68, and today a major tourist center.

The women were put up overnight in a local hotel and picked up early the next morning by an army vehicle with a driver and an officer as an interpreter-guide. The army personnel were delighted to get away from the mundane of their regular duties and take the two young American women to the listed MIA site.

When Captain Nguyen Ai Quoc introduced himself, Jackie studied him for a moment and remarked, “Really? Ho Chi Minh?”

Captain Quoc replied, “I’m impressed. You’re the first American I’ve ever met who knows one of the original names of our former president. My father was a well-decorated patriot of the resistance. He named me after the founder of our Republic.”

That set the stage for a pleasant drive to the A Shau Valley. Laura found it hard to reconcile what she knew and believed of Vietnam, and enjoyed engaging the captain in questions, of which he was delighted to give her answers. Having brought her camera, she was free to take all the pictures she wanted . . . and did.

As they cut off the main highway and traveled along progressively less-developed roads, the captain explained that they had already surveyed the forested area where the few remains were found. “There’s not really all that much there, but we did find some sort of personal shrine, so it means something to someone. We traced some of the material at the shrine as coming from a village not that far away. I suggest we go to the village first,” suggested the captain, “and, later we can visit the area where your relative was apparently last known to be, okay?”

The women readily agreed. It was close to noon when the vehicle came upon the village carved out of the thick forested area on the fringe of the A Shau Valley. They were enthusiastically greeted by jumping children and barking dogs. When they saw the obviously foreign women, they grew even more openly curious.

Waiting patiently in the vehicle, parked off-trail near a strange looking tree, they were soon greeted by several elders apparently led by an old woman, the senior elder of the village. After a brief talk w/the captain, they were all invited to sit at some comfortable twine-woven benches under the tree.

Given some sweetmeats, fruit and tea, it was soon made clear by the captain translating comments by the elder woman that they were waiting for the arrival of her son, the village leader, from the fields where he had been sent for.

Jackie and Laura were admiring the area. The tree was quite large and provided ample shade from the sun. Fruits were hanging from its branches, which seemed strange to the women as they were a variety of different types. Laura was about to ask about this when a small group of men arrived.

The elderly man talked with the captain for a few minutes as he studied the women. He was eventually introduced as Le Kim Chu, the son of the elderly woman. After a few minutes of polite chatter, Chu looked at Laura with what seemed like greater curiosity. He seemed to have made a decision when he asked to be excused.

Ho Chi Minh City War Museum…

Le Kim Chu was a well-known and decorated veteran of the Resistance to the American War, as the Vietnamese referred to it, the captain explained. Returning shortly, having cleaned up a bit, Chu performed a short ritual before a shrine at the base of the tree, and after taking a purple cloth out of a box built into the shrine, he rejoined the group.

He seemed quite somber to Jackie, but the politeness of the Vietnamese she found could assume several forms . . . almost always respectful. Addressing the captain but mostly looking at Laura, Chu started his story. Chu’s mother sat by his side, and a group of other elders and a few of the older children silently sat on the ground nearby.

The captain paused from time to time as he studied the veteran before him, clearly entranced by what he was saying and repeating the words and tone almost exactly in the cadence they were delivered. It started off w/a brief history of the A Shau Valley resistance and campaigns and his own history as a young boy born into conflict and war. Chu explained that in 1969 he was 14-yrs-old.

When Chu got to the time of the American patrol’s deadly confrontation w/the surviving villagers, he grew even more somber. Assigned to nearby defense work, Chu and his resistance unit–what the Americans referred to as Viet Cong—heard some of the initial firing and they started toward the area.

When he came upon the forest scene, he saw his younger sister on the ground, naked and her blood spurting from her throat. An American soldier standing near her spun around w/his weapon and Chu instinctively cut loose w/his own. The American went down in a shower of blood and bone. Laura visibly gasped, but Chu clearly felt compelled to tell the raw story.

He later learned from the boy who had been w/her, that he had only seen one American. That soldier, he said, had caught the girl when she told the younger boy to run and hide. A quick analysis of the scene, made it clear to Chu what happened. The American that he had killed was not her rapist and killer. In fact, he had just apparently shot the other American. The fog of war . . .

After a few moments of allowing the women to digest this, Chu continued thru the translator, “When the rest of my force arrived, we transported the bodies of my sister and the soldier I had killed to another area where we honorably buried them together.

Reaching down, Chu unfolded the velvet cloth, which contained several articles, including a ring, dog-tags and a wallet. He passed all the contents over to Laura, the grand-daughter of the man he had mistakenly shot.

Laura could immediately see thru her tears that they were her grandfather’s tags, and the wallet was completely intact w/his various ID, photos and money.

Chu continued, “After the war, we planted this fruit tree over their burial spot w/the shrine and have nurtured it ever since. We also located our small village here . . . to us this is a holy area; the spirits of my sister and your grandfather watch over us. Over time we have grafted the branches of other fruit trees to the original one, and that is what you see today.”

The Lotus Pond…

Laura stared at the tree and the ground for some time. Jackie noticed that the captain in reciting this story, had silent tears flowing down his face . . . very unusual in her experience of the normally stoic Vietnamese.

The captain started to tell the women what procedures were in place to exhume the remains for transport back to the US–.

Surveying Chu and his mother and the surrounding area for a few moments, Laura turned to Jackie, but saying to all, “I don’t know what the Embassy and Army will say, but I’m sure my mother will agree that there is no better tribute to Christopher than the honor and burial that he’s found here.”

Turning to Le Kim Chu, she added, “I want to thank you on behalf of my family, and my grandfather. I can think of no more fitting memorial than that he has been embodied by this tree and that he lies in peace and honor with your sister by his side.”

It was at that moment that for the first time since he was 14-yrs-old, Le Kim Chu, Hero of the Vietnamese Revolution, broke down sobbing in his mother’s arms.

There was nothing for anyone to add. After another hour at which Chu asked and Laura answered, she told him who Christopher was and of her family. Chu quietly spoke of his sister’s brief life.

When they left the village, they traveled first to the Valley site and then back to the base for transport to Ho Chi Minh City and home.

Dr. Publico (Nick Medvecky, PsyD), May 2016…