I prepared an article for the Anarcho-Syndicalist Review summarizing the main points from my latest book, We Do Not Fear Anarchy – We Invoke It: The First International and the Emergence of the Anarchist Movement, which was published in ASR #63 (Winter 2015). It’s a bit long for my blog, but here it is. The full book can be ordered from AK Press or your local bookseller.

The Spirit of Anarchy

We Do Not Fear Anarchy: A Summary of My Book on the First International and the Emergence of the Anarchist Movement

September 2014 marked the 150th anniversary of the founding of the International Workingmen’s Association (IWMA – in the Romance languages, the AIT – now commonly referred to as the First International). While much is often made of the dispute between Marx and Bakunin within the International, resulting in Bakunin’s expulsion in 1872, more important from an anarchist perspective is how anarchism as a distinct revolutionary movement emerged from the debates and conflicts within the International, not as the result of a personal conflict between Marx and Bakunin, but because of conflicting ideas regarding working class liberation.

Many members of the International, particularly in Italy, Spain and French speaking Switzerland, but also in Belgium and France, took to heart the statement in the International’s Preamble that the emancipation of the working class is the task of the workers themselves. They envisioned the International as a fighting organization for the daily struggle of the workers against the capitalists for better working conditions, but also looked to the International as a federation of workers across national borders that would provide the impetus for revolutionary change and the creation of a post-revolutionary socialist society based on workers’ self-management and voluntary federation. It was from out of these elements in the International that the first European anarchist movements arose.

When the International was founded in September 1864 by French and British trade unionists, any anarchist tendencies were then very weak. The French delegates at the founding of the First International regarded themselves as “mutualists,” moderate followers of Proudhon, not anarchist revolutionaries. They supported free credit, workers’ control, small property holdings and equivalent exchange of products by the producers themselves. They wanted the International to become a mutualist organization that would pool the financial resources of European workers to provide free credit for the creation of a system of producer and consumer cooperatives that would ultimately displace the capitalist economic system.

Founding Congress of the International, September 28, 1864

The first full congress of the International was not held until September 1866, in Geneva, Switzerland, with delegates from England, France, Germany and Switzerland. Although the French delegates did not call for the immediate abolition of the state, partly because such radical talk would only result in the International being banned in France, then under the dictatorship of Napoleon III, they did express their rejection of the state as a “superior authority” that would think, direct and act in the name of all, stifling initiative. They shared Proudhon’s view that social, economic and political relations should be based on contracts providing reciprocal benefits, thereby preserving the independence and equality of the contracting parties. The French delegates distinguished this “mutualist federalism” from a communist government that would rule over society, regulating all social and economic functions.

At the next Congress of the International in Laussane, Switzerland, in September 1867, César De Paepe, one of the most influential Belgian delegates, debated the more conservative French mutualists on the collectivization of land, which he supported, arguing that if large industrial and commercial enterprises, such as railways, canals, mines and public services, should be considered collective property to be managed by companies of workers, as the mutualists agreed, then so should the land. The peasant and farmer, as much as the worker, should be entitled to the fruits of their labour, without part of that product being appropriated by either the capitalists or the landowners. De Paepe argued that this “collectivism” was consistent with Proudhon’s “mutualist program,” which demanded “that the whole product of labour shall belong to the producer.” However, it was not until the next congress in Brussels in September 1868 that a majority of delegates adopted a collectivist position which included land as well as industry.

At the Brussels Congress, De Paepe also argued that the workers’ “societies of resistance” and trade unions, through which they organized and coordinated their strike and other activities, constituted the “embryo” of those “great companies of workers” that would replace the “companies of the capitalists” by eventually taking control of collective enterprises. For, according to De Paepe, the purpose of trade unions and strike activity was not merely to improve existing working conditions but to abolish wage labour. This could not be accomplished in one country alone, but required a federation of workers in all countries, who would replace the capitalist system with the “universal organization of work and exchange.” Here we have the first public expression within the International of the basic tenets of revolutionary and anarchist syndicalism: that through their own trade union organizations, by which the workers waged their daily struggles against the capitalists, the workers were creating the very organizations through which they would bring about the social revolution and reconstitute society, replacing capitalist exploitation with workers’ self-management.

The First International

After the Brussels Congress, Bakunin and his associates applied for their group, the Alliance of Socialist Democracy, to be admitted into the International. The Alliance stood for “atheism, the abolition of cults and the replacement of faith by science, and divine by human justice.” The Alliance supported the collectivist position adopted at the Brussels Congress, seeking to transform “the land, the instruments of work and all other capital” into “the collective property of the whole of society,” to be “utilized only by the workers,” through their own “agricultural and industrial associations.”

In Bakunin’s contemporaneous program for an “International Brotherhood” of revolutionaries, he denounced the Blanquists and other like-minded revolutionaries who dreamt of “a powerfully centralized revolutionary State,” for such “would inevitably result in military dictatorship and a new master,” condemning the masses “to slavery and exploitation by a new pseudo-revolutionary aristocracy.” In contrast, Bakunin and his associates did “not fear anarchy, we invoke it.” Bakunin envisaged the “popular revolution” being organized “from the bottom up, from the circumference to the center, in accordance with the principle of liberty, and not from the top down or from the center to the circumference in the manner of all authority.”

In the lead up to the Basle Congress of the International in September 1869, Bakunin put forward the notion of the general strike as a means of revolutionary social transformation, observing that when “strikes spread out from one place to another, they come very close to turning into a general strike,” which could “result only in a great cataclysm which forces society to shed its old skin.” He also supported, as did the French Internationalists, the creation of “as many cooperatives for consumption, mutual credit, and production as we can, everywhere, for though they may be unable to emancipate us in earnest under present economic conditions, they prepare the precious seeds for the organization of the future, and through them the workers become accustomed to handling their own affairs.”

Bakunin argued that the program of the International must “inevitably result in the abolition of classes (and hence of the bourgeoisie, which is the dominant class today), the abolition of all territorial States and political fatherlands, and the foundation, upon their ruins, of the great international federation of all national and local productive groups.” Bakunin was giving a more explicitly anarchist slant to the idea, first broached by De Paepe at the Brussels Congress, and then endorsed at the Basle Congress in September 1869, that it was through the International, conceived as a federation of trade unions and workers’ cooperatives, that capitalism would be abolished and replaced by a free federation of productive associations.

Jean-Louis Pindy, a delegate from the carpenters’ Chambre syndicale in Paris, expressed the views of many of the Internationalists at the Basle Congress when he argued that the means adopted by the trade unions must be shaped by the ends which they hoped to achieve. He saw the goal of the International as being the replacement of capitalism and the state with “councils of the trades bodies, and by a committee of their respective delegates, overseeing the labor relations which are to take the place of politics,” so that “wage slavery may be replaced by the free federation of free producers.” The Belgian Internationalists, such as De Paepe and Eugène Hins, put forward much the same position, with Hins looking to the International to create “the organization of free exchange, operating through a vast section of labour from one end of the world to another,” that would replace “the old political systems” with industrial organization, an idea which can be traced back to Proudhon, but which was now being given a more revolutionary emphasis.

The Basle Congress therefore declared that “all workers should strive to establish associations for resistance in their various trades,” forming an international alliance so that “the present wage system may be replaced by the federation of free producers.” This was the highwater mark of the federalist, anti-authoritarian currents in the First International, and it was achieved at its most representative congress, with delegates from England, France, Belgium, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Italy and Spain.

Bakunin speaking at the Basel Congress 1869

Bakunin attended the Congress, drawing out the anarchist implications of this position. He argued that because the State provided “the sanction and guarantee of the means by which a small number of men appropriate to themselves the product of the work of all the others,” the political, juridical, national and territorial State must be abolished. Bakunin emphasized the role of the state in creating and perpetuating class privilege and exploitation, arguing that “if some individuals in present-day society do acquire… great sums, it is not by their labor that they do so but by their privilege, that is, by a juridically legalized injustice.”

Bakunin expressed his antipathy, shared by other members of the International, to revolution from above through a coercive state apparatus. With respect to peasant small holders, he argued that “if we tried to expropriate these millions of small farmers by decree after proclaiming the social liquidation, we would inevitably cast them into reaction, and we would have to use force against them to submit to the revolution.” Better to “carry out the social liquidation at the same time that you proclaim the political and juridical liquidation of the State,” such that the peasants will be left only with “possession de facto” of their land. Once “deprived of all legal sanction,” no longer being “shielded under the State’s powerful protection,” these small holdings “will be transformed easily under the pressure of revolutionary events and forces” into collective property.

The Basle Congress was the last truly representative congress of the International. The Franco-Prussian War in 1870 and the Paris Commune in 1871 made it difficult to hold a congress, while the Hague Congress of 1872 was stacked by Marx and Engels with delegates with dubious credentials. One must therefore look at the activities of the various International sections themselves between 1869 and 1872 to see how the anti-authoritarian, revolutionary collectivist currents in the International eventually coalesced into a European anarchist movement.

In France, Eugène Varlin, one of the International’s outstanding militants, described the position adopted “almost unanimously” by the delegates at the Basle Congress as “collectivism, or non-authoritarian communism.” Varlin expressed the views of many of the French Internationalists when he wrote that the workers’ own organizations, the trade unions and societies of resistance and solidarity, “form the natural elements of the social structure of the future.” By March 1870, he was writing that short “of placing everything in the hands of a highly centralized, authoritarian state which would set up a hierarchic structure from top to bottom of the labour process… we must admit that the only alternative is for the workers themselves to have the free disposition and possession of the tools of production… through co-operative associations in various forms.”

Bakunin & Fanelli with other Internationalists

The revolutionary syndicalist ideas of the Belgians and Bakunin’s more explicitly anarchist views were also being spread in Spain. Echoing De Paepe’s comments from the Brussels Congress, the Spanish Internationalists described the International as containing “within itself the seeds of social regeneration… it holds the embryo of all future institutions.” They founded the Federación Regional Española (FRE – Spanish Regional Federation) in June 1870, which took an anarchist position. One of its militants, Rafael Farga Pellicer, declared that: “We want the end to the domination of capital, the state, and the church. Upon their ruins we will construct anarchy, and the free federation of free associations of workers.” In addition, the FRE adopted a form of organization based on anarchist principles, “from the bottom upward,” with no paid officers or trade union bureaucracy.

In French speaking Switzerland, as a result of a split between the reformist minority, supported by Marx, and the anti-authoritarian collectivist majority, allied with Bakunin, the Jura Federation was created in 1870. The Jura Federation adopted an anarchist stance, declaring that “all participation of the working class in the politics of bourgeois governments can result only in the consolidation and perpetuation of the existing order.”

On the eve of the Franco-Prussian War during the summer of 1870, the French Internationalists took an anti-war stance, arguing that the war could only be a “fratricidal war” that would divide the working class, leading to “the complete triumph of despotism.” The Belgian Internationalists issued similar declarations, denouncing the war as a war of “the despots against the people,” and calling on them to respond with a “war of the people against the despots.”

This was a theme that Bakunin was soon to expand upon in his Letters to a Frenchman on the Present Crisis, published in September 1870. Although many of the French Internationalists abandoned their anti-war stance, Bakunin argued that revolutionaries should seek to transform the war into a country wide insurrection that would then spread the social revolution across Europe. With the French state in virtual collapse, it was time for the “people armed” to seize the means of production and overthrow their oppressors, whether the French bourgeoisie or the German invaders.

For the social revolution to succeed, Bakunin argued that it was essential that the peasants and workers band together, despite the mutual distrust between them. The peasants should be encouraged to “take the land and throw out those landlords who live by the labour of others,” and “to destroy, by direct action, every political, juridical, civil, and military institution,” establishing “anarchy through the whole countryside.” A social revolution in France, rejecting “all official organization” and “government centralization,” would lead to “the social emancipation of the proletariat” throughout Europe.

Shortly after completing his Letters, Bakunin tried to put his ideas into practice, travelling to Lyon, where he met up with some other Internationalists and revolutionaries. Bakunin and his associates issued a proclamation announcing the abolition of the “administrative and governmental machine of the State,” the replacement of the judicial apparatus by “the justice of the people,” the suspension of taxes and mortgages, with “the federated communes” to be funded by a levy on “the rich classes,” and ending with a call to arms. Bakunin and his confederates briefly took over City Hall, but eventually the National Guard recaptured it and Bakunin was arrested. He was freed by a small group of his associates and then made his way to Marseilles, eventually returning to Switzerland. A week after Bakunin left Marseilles, there was an attempt to establish a revolutionary commune there and, at the end of October, in Paris.

In Paris, the more radical Internationalists did not take an explicitly anarchist position, calling instead for the creation of a “Workers’ and Peasants’ Republic.” But this “republic” was to be none other than a “federation of socialist communes,” with “the land to go to the peasant who cultivates it, the mine to go to the miner who exploits it, the factory to go to the worker who makes it prosper,” a position very close to that of Bakunin and his associates.

After the proclamation of the Paris Commune on March 18, 1871, the Parisian Internationalists played a prominent role. On March 23, 1871, they issued a wall poster declaring the “principle of authority” as “incapable of re-establishing order in the streets or of getting factory work going again.” For them, “this incapacity constitutes [authority’s] negation.” They were confident that the people of Paris would “remember that the principle that governs groups and associations is the same as that which should govern society,” namely the principle of free federation.

The Communes’ program, mostly written by Pierre Denis, a Proudhonist member of the International, called for the “permanent intervention of citizens in communal affairs” and elections with “permanent right of control and revocation,” as well as the “total autonomy of the Commune extended to every township in France,” with the “Commune’s autonomy to be restricted only by the right to an equal autonomy for all the other communes.” The Communards assured the people of France that the “political unity which Paris strives for is the voluntary union of all local initiative, the free and spontaneous cooperation of all individual energies towards a common goal: the well-being, freedom and security of all.” The Commune was to mark “the end of the old governmental and clerical world; of militarism, bureaucracy, exploitation, speculation, monopolies and privilege that have kept the proletariat in servitude and led the nation to disaster.”

For the federalist Internationalists, this did not mean state ownership of the economy, but collective or social ownership of the means of production, with the associated workers themselves running their own enterprises. As the Typographical Workers put it, the workers shall “abolish monopolies and employers through adoption of a system of workers’ co-operative associations. There will be no more exploiters and no more exploited.”

The social revolution was pushed forward by female Internationalists and radicals, such as Nathalie Lemel and Louise Michel. They belonged to the Association of Women for the Defence of Paris and Aid to the Wounded, which issued a declaration demanding “No more bosses. Work and security for all — The People to govern themselves — We want the Commune; we want to live in freedom or to die fighting for it!” They argued that the Commune should “consider all legitimate grievances of any section of the population without discrimination of sex, such discrimination having been made and enforced as a means of maintaining the privileges of the ruling classes.”

Nevertheless, the Internationalists were a minority within the Commune, and not even all of the Parisian Internationalists supported the socialist federalism espoused in varying degrees by Varlin, Pindy and the more militant Proudhonists. The federalist and anti-authoritarian Internationalists felt that the Commune represented “above all a social revolution,” not merely a change of rulers. They agreed with the Proudhonist journalist, A. Vermorel, that “there must not be a simple substitution of workers in the places occupied previously by bourgeois… The entire governmental structure must be overthrown.”

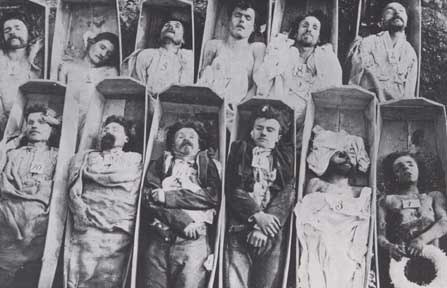

The Commune was savagely repressed by French state forces, with the connivance of the Prussians, leading to wholesale massacres that claimed the lives of some 30,000 Parisians, including leading Internationalists like Varlin, and the imprisonment and deportation of many others, such as Nathalie Lemel and Louise Michel. A handful of Internationalists, including Pindy, went into hiding and eventually escaped to Switzerland.

Executed Communards

For Bakunin, what made the Commune important was “not really the weak experiments which it had the power and time to make,” but “the ideas it has set in motion, the living light it has cast on the true nature and goal of revolution, the hopes it has raised, and the powerful stir it has produced among the popular masses everywhere, and especially in Italy, where the popular awakening dates from that insurrection, whose main feature was the revolt of the Commune and the workers’ associations against the State.” Bakunin’s defence of the Commune against the attacks of the veteran Italian revolutionary patriot, Guiseppe Mazzini, played an important role in the “popular awakening” in Italy, and the rapid spread of the International there, from which the Italian anarchist movement sprang.

The defeat of the Paris Commune led Marx and Engels to draw much different conclusions. For them, what the defeat demonstrated was the necessity for working class political parties whose purpose would be the “conquest of political power.” They rammed through the adoption of their position at the September 1871 London Conference of the International, and took further steps to force out of the International any groups with anarchist leanings, which by this time included almost all of the Italians and Spaniards, the Jura Federation, many of the Belgians and a significant proportion of the surviving French members of the International.

In response, the Jura Federation organized a congress in Sonvillier, Switzerland, in November 1871. Prominent Communards and other French refugees also attended. They issued a Circular to the other members of the International denouncing the General Council’s actions, taking the position that the International, “as the embryo of the human society of the future, is required in the here and now to faithfully mirror our principles of freedom and federation and shun any principle leaning towards authority and dictatorship,” which was much the same position as had been endorsed by a majority of the delegates to the 1869 Basel Congress.

The Belgian, Italian and Spanish Internationalists supported the Jura Federation’s position, with the Italian and Spanish Internationalists adopting explicitly anarchist positions. Even before the London Conference, the Spanish Internationalists had declared themselves in favour of “collective property, anarchy and economic federation,” by which they meant “the free universal federation of free agricultural and industrial workers’ associations.” The Italian Internationalists rejected participation in existing political systems and in August 1872 called on the federalist and anti-authoritarian sections of the International to boycott the upcoming Hague Congress and to hold a congress of their own. Marx and Engels manipulated the composition of the Hague Congress to ensure a majority that would affirm the London Conference resolution on political action, expel Bakunin and his associate, James Guillaume of the Jura Federation, from the International, and transfer the General Council to New York to prevent the anti-authoritarians from challenging their control.

Barely a week after the Hague Congress in September 1872, the anti-authoritarians held their own congress in St. Imier where they reconstituted the International along federalist lines. The St. Imier Congress was attended by delegates from Spain, France, Italy, Switzerland and Russia. For them, “the aspirations of the proletariat [could] have no purpose other than the establishment of an absolutely free economic organization and federation, founded upon the labour and equality of all and absolutely independent of all political government.” Consequently, turning the London Conference’s resolution on its head, they declared that “the destruction of all political power is the first duty of the proletariat.”

They regarded “the strike as a precious weapon in the struggle” for the liberation of the workers, preparing them “for the great and final revolutionary contest which, destroying all privilege and all class difference, will bestow upon the worker a right to the enjoyment of the gross product of his labours.” Here we have the subsequent program of anarcho-syndicalism: the organization of workers into trade unions and similar bodies, based on class struggle, through which the workers will become conscious of their class power, ultimately resulting in the destruction of capitalism and the state, to be replaced by the free federation of the workers based on the organizations they created themselves during their struggle for liberation.

The resolutions from the St. Imier Congress were ratified by the Italian, Spanish, Jura, Belgian and, ironically, the American federations of the International, with most of the French sections also approving them. The St. Imier Congress marks the true emergence of a European anarchist movement, with the Italian, Spanish and Jura Federations of the International following anarchist programs. While there were anarchist elements within the Belgian Federation, by 1874, under the influence of De Paepe, the Belgians had come out in favour of a “public administrative state” that the anarchist federations in the anti-authoritarian International opposed. The French Internationalists contained a prominent anarchist contingent, but it was not until 1881 that a distinctively anarchist movement arose there.

In his memoirs, Kropotkin wrote that if the Europe of the late 1870s “did not experience an incomparably more bitter reaction than it did” after the Franco-Prussian War and the fall of the Paris Commune, “Europe owes it… to the fact that the insurrectionary spirit of the International maintained itself fully intact in Spain, in Italy, in Belgium, in the Jura, and even in France itself.” One can say, with equal justification, that anarchism itself, as a revolutionary movement, owes its existence to that same revolutionary spirit of the International from which it was born in the working class struggles in Europe during the 1860s and early 1870s. It was from those struggles, and the struggles within the International itself regarding how best to conduct them, that a self-proclaimed anarchist movement emerged.

Robert Graham