The Originals – Elvis Presley Vol. 2

The first part of the Elvis Originals covered (as it were) the Rock & Roll years and early post-GI period. Here we have the originals of songs Elvis covered in the 1960s and ’70s.

Elvis Presley’s artistic decline in the1960s is symbolised by the coincidence of his most derided movie, Clambake, which opened at about the same time as The Beatles released their groundbreaking Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band LP. A year later, in 1968, Elvis’ live TV special marked the comeback of Elvis the Entertainer. Elvis the Recording Artist, however, had not had a #1 hit in seven years when in January 1969 he entered the famous American Sound Studios in Memphis.

At first the old soul music veterans at the studio were dubious about working with the washed-up ex-king of rock ‘n’ roll. Elvis soon had them convinced otherwise. Eight days into the session, on January 20, he recorded the Mac Davis-penned In The Ghetto; two days later Suspicious Minds, which by the end of 1969 would top the US charts.

Suspicious Minds was written by American Sound Studios in-house writer Mark James (whose real name was Francis Zambon), who also wrote hits such as It’s Only Love and Hooked On A Feeling for his friend, country singer BJ Thomas. And it was BJ Thomas was in line to record Suspicious Minds, which James had already released on record to no commercial success, before the song was given to Presley. Elvis insisted on recording the song even when his manager, “Colonel” Tom Parker, threatened that he wouldn’t over the question of publishing rights (always an issue with Parker).

Elvis would record four more songs written or co-written by James: Always On My Mind, Raised On A Rock, Moody Blue (which James released in 1975) and It’s Only Love. Chips Moman produced James’ 1968 version of Suspicious Minds, thereby creating a handy template which he returned to when producing Elvis’ version.

Depending on where you live and how old you are, Always On My Mind may be Elvis’ song or Willie Nelson’s, or perhaps the Pet Shop Boys’ (who had a hit with it in late 1987 after earlier performing it on a TV special to mark the 10th anniversary of Elvis’ death). Originally it was Brenda Lee’s, released in May 1972. It was not a big hit for her, reaching only #45 in the country charts. Somehow Elvis heard it and found the lyrics expressed his emotions at a time when the marriage to Priscilla was collapsing. He recorded it later in 1972. Released as the b-side to the top 20 hit Separate Ways, Always On My Mind was a #16 hit in the country charts. In the UK, however it was a top 10 hit, and became better know in Europe than in the US.

Another artist whose songs Elvis loved to cover was Jerry Reed, featured here with Guitar Man and US Male, originally released by Reed in 1966 and covered by Elvis two years later. Jerry Reed was a country singer who toiled for a dozen years before scoring a hit in 1967 with Tupelo Mississippi Flash — a song about Elvis. The same year Elvis chose to record Reed’s Guitar Man (the composer is listed as Jerry Hubbard, the singer’s real surname), and Reed played guitar on it. For Elvis, Guitar Man was a redemption of sorts after the degradation of Clambake. His performance of the song at the Elvis ’68 Comeback Special is one of the best moments of the show.

The writers most associated with Elvis are Jerry Leiber & Mike Stoller. Their Bossa Nova Baby has been unjustly regarded by some as a novelty number from an Elvis movie (1963’s Fun In Acapulco). Even Elvis is said to have been embarrassed by it. If so, he had no cause: it may not be a bossa nova — it’s too fast for that — but it has an infectious tune and a genius keyboard riff which begs to be sampled widely. Perhaps it was the lyrics which had Elvis allegedly shamefaced, but the lines “she said, ‘Drink, drink, drink/Oh, fiddle-de-dink/I can dance with a drink in my hand’” are not much worse than some of the doggerel our man was forced to croon in his movie career as singing racing driver/pineapple heir/bus conductor. Or perhaps Elvis was embarrassed by the idea of including a notional bossa nova number in a movie set in Mexico.

Tippie & the Clovers, who were signed to Leiber and Stoller’s Tiger label, recorded it first in 1962 to cash in on the bossa nova craze. Apparently the composer’s preferred the Clovers’ version over Elvis’. These were the same Clovers, incidentally, who had scored a #23 hit with Love Potion No. 9 (also written by Leiber & Stoller and later covered to greater chart effect by the Searchers) on Atlantic in 1959.

Elvis was greatly influenced by the sounds of Rhythm & Blues on the one hand and country music on the other — Arthur Crudup and Hank Snow. A third profound influence was gospel. Here, too, Elvis drew from across the colour line. Often he was one of the few white faces at black church services (as a youth in Tupelo, he lived in a house designated for white families but located at the edge of a black township), but he also loved the white gospel-country sounds created by the likes of the Louvin Brothers, whom he once regarded as his favourite act.

Indeed, gospel was the genre Elvis loved the most. In recording studios, he would warm up with gospel numbers. When he jammed with Jerry Lee Lewis and Carl Perkins in the Sun studio (Johnny Cash left before any of the misnamed Million Dollar Quartet session was recorded), much of the material consisted of sacred music. At the height of his hip-gyrating greatness, he recorded an EP of spirituals titled Peace In The Valley. And let’s not forget that the only three Grammies Elvis ever received were for gospel recordings.

Elvis’ biggest gospel hit was Crying In The Chapel, which had been written in 1953 by Artie Glenn for his son Darrell, who performed it in the country genre. The same year, the R&B band Sonny Til & the Orioles — progenitors of the doo wop style of the late ’50s and the first of a succession of bird-themed bandnames — scored a #11 hit with the song (around the same time, a pop version by June Valli reached #4). It was the Orioles’ recording from which Elvis drew inspiration in his version, recorded shortly after he returned from the army in 1960. It was not released, at Tom Parker’s command, because Artie Glenn refused to share the rights to the song with the cut-throat publishing company of Elvis repertoire, Hill & Range. And with good reason, for the song continued to be a hit by several artists. Eventually Hill & Range secured the ownership. When Crying In The Chapel was eventually released in 1965, it was not only a US hit (his first top 10 single in two years), but also topped the UK charts.

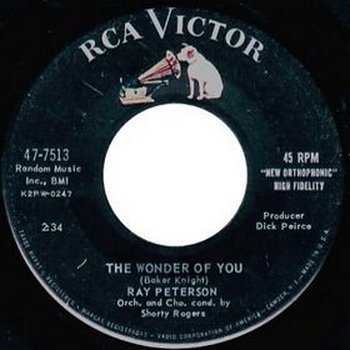

Apparently written for Perry Como, The Wonder Of You was first recorded by Ray Peterson (he of Tell Laura I Love Her notoriety) in 1959, scoring a moderate hit with it. Peterson, who died in 2005, later liked to recount the story of how Elvis sought his permission to record the song. “He asked me if I would mind if he recorded The Wonder Of You. I said: ‘You don’t have to ask permission; you’re Elvis Presley.’ He said: ‘Yes, I do. You’re Ray Peterson.’” Not that Peterson owned the rights to the song, or was particularly famous for singing it.

Elvis recorded the song live on stage in Las Vegas on February 18, 1970. It was released as a single a couple of months later and was a big hit on both sides of the Atlantic, topping the UK charts for six weeks. It was also his last UK #1 during his lifetime.

Elvis did not particularly like Burning Love; if he didn’t record it under protest, he certainly was not going to spend much time on it. Where 16 years earlier he’d spend 30-odd takes on the spontaneous sounding Hound Dog, he recorded Burning Love in only six takes. The production values were pretty poor: Elvis’ voice sounds tinny, but not for lack of trying. But listen to the drumming! Strange then that this slack recording scored big in the US (#2 on Billboard; the final top 10 hit in his lifetime) and UK (#7).

A year previously, in 1971, the soul singer Arthur Alexander (whom we will meet again when we turn to originals of Beatles songs) recorded Burning Love, releasing it in January 1972, two months before Elvis recorded it. A fine recording in the southern soul tradition, it made no impact. The song’s writer, Dennis Linde, recorded it in 1973 — his version, included here, recalls the sound of Creedence Clearwater Revival.

With its Bo Diddley-inspired guitar riff and flamenco-meets-rock ‘n’ roll feel, 1961’s (Marie’s The Name) His Latest Flame served as a welcome, albeit temporary, break from Elvis’ succession of easy listening fare such as It’s Now Or Never, Surrender and Are You Lonesome Tonight (though within a few months, he’d top the charts with another standard ballad, Can’t Help Falling In Love). Like all these songs, His Latest Flame was not an original.

The song was written by Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, who wrote some 20 Elvis songs — including Viva Las Vegas, their demo of which is included here — as well as hits for acts such as The Drifters (Save The Last Dance For Me) and Dion (Teenager In Love). Although reportedly written specifically for Elvis, His Latest Flame was first offered to Bobby Vee, who turned it down. Instead Del Shannon recorded the song in May 1961, with a view to releasing it as a follow-up single for his big hit Runaway. In the event, he decided to run with the non-classic Hats Off To Larry instead. His Latest Flame was released on the Runaway With Del Shannon LP in June ’61. The same month Elvis recorded his version, which was released in the US in August. Due to the arcane method of compiling the US charts, the His Latest Flame peaked at #4 and its flip side, Little Sister (another Pomus/Shuman composition) at #5. It topped the charts in Britain.

Shuman tended to tout his co-composition by way of demos on which he sang himself. The demo for His Latest Name is much closer to Elvis’version than Shannon’s, a less smooth, more soulful interpretation which has something of a mariachi band feel, using brass to accentuate the Diddley-style riff (which the Smiths famously sampled 24 years later on Rusholme Ruffians).

It’s Now Or Never and Surender were based on old Italian songs; Can’t Help Falling In Love on an old French melody. This is the song which ignorant callers to radio stations tend to request by the title “Wise Man Say”. The fictitious title is not entirely off the mark: the lyrics were co-written by a pair of alleged mafia associates, Hugo Peretti and Luigi Creatore, with George David Weiss. Peretti and Creatore were partners with mafioso Mo Levy in the Roulette record label (named after the game that “Colonel” Tom Parker was addicted to), which the FBI identified as a source of revenue for the Genovese crime family. The trio also wrote the lyrics for The Lion Sleeps Tonight, a song stolen from South African musician Solomon Linda.

The melody of Can’t Help Falling In Love borrows from the old French love song Plaisir d’amour, composed in 1785 by Johann Paul Aegidius Martini. It was first recorded in 1902 by Monsieur Fernand (real name Emilio de Gogorza), and subsequently by a zillion others, including in 1908 by the baritone Charles Gilibert (1866-1910). It may be a little more accurate to describe Can’t Help Falling In Love as an adaptation rather than as a cover. While the similarities are sufficiently evident to mark Plaisir d’amour as the basis for the song, it certainly has been innovated on.

The song was adapted in 1961 for Elvis’ Blue Hawaii movie (the title track was a cover of a Bing Crosby song, of all things). Reportedly, neither the film’s producers nor Elvis’ label, RCA, liked the song much. Elvis, however, insisted on recording it. Elvis often was his best A&R man, and so it was here. The song was initially released as the b-side of Rock-A-Hula Baby (you do know how that one goes, no?). In the event, Can’t Help became the big hit, reaching #2 in the US and #1 in the UK. It also became a signature song for Elvis who would invariably include it in his concerts. Indeed, it was the last song he performed live on stage in Indianapolis on 26 June 1977, Elvis’ final concert.

The last five tracks in the mix are demo versions recorded by the songs’ composers. And in the case of A Little Less Conversation, Elvis was the progenitor for the later version which became a hit in 2002 under the Elvis vs JXL moniker.

1. Del Shannon – His Latest Flame (1961)

2. Clyde McPhatter & The Drifters – Such A Night (1956)

3. The Coasters – Girls! Girls! Girls! (1962)

4. Tippie & the Clovers – Bossa Nova Baby (1962)

5. Jerry Reed – Guitar Man (1967)

6. Mark James – Suspicious Minds (1968)

7. Arthur Alexander – Burning Love (1972)

8. Tony Joe White – I’ve Got A Thing About You Baby (1972)

9. Jerry Reed – U.S. Male (1966)

10. Wynn Stewart – Long Black Limousine (1958)

11. Brenda Lee – Always On My Mind (1972)

12. Ferlin Husky – There Goes My Everything (1966)

13. Ray Peterson – The Wonder Of You (1959)

14. Micky Newbury – An American Trilogy (1971)

15. Tony Joe White – Polk Salad Annie (1968)

16. Mark James – Moody Blue (1975)

17. Buffy Sainte-Marie – Until It’s Time For You To Go (1965)

18. Les Paul & Mary Ford – I Really Don’t Want To Know (1954)

19. Darrell Glenn – Crying In The Chapel (1953)

20. Bing Crosby – Blue Hawaii (1937)

21. Charles Gilibert – Plaisir d’amour (1908)

22. Elvis Presley – A Little Less Conversation (1968)

23. Laying Maetine Jr. – Way Down (1976)

24. Mort Shuman – His Latest Flame

25. Mort Shuman – Viva Las Vegas

26. Bill Giant – Devil In Disguise

27. Dennis Linde – Burning Love

Recent Comments