The following post is the second part in our notes on Trump. Part one can be found here. We’ll look at the limits and potentials of the forces arrayed against Trump in part three.

In our last post, we located the Trump regime within a global right wing resurgence enabled by capitalist crisis and the failures of social democracy. Now we can examine how this resurgence developed in the U.S. context. In this piece, we will explore how conservative hegemony emerged from the crisis of the 1970s, developed through the Reagan years and exhausted itself in the Obama era. We will then trace how Trump builds on the history of conservative hegemony even as he rends it in two, and outline the degree to which the incoming Trump regime stands to deepen authoritarianism.

For decades, the U.S. neoliberal elite legitimated falling wages and living standards by keeping the economy afloat with successive credit-fueled bubbles and playing on white racialist resentments. But this strategy began to collapse with the onset of the Great Recession, after years of erosion. Now the the content of conservative hegemony is turning against itself, and Trumpism is the result. On one side are neoliberal efforts to contract social reproduction, and thereby struggle to renew the profitability of capitalism. On the other side are appeals to white populist nationalism, which increasingly undermine the norms of the bourgeois state and civil society. Both elements have been integral to neoliberal rule, but they can also become contradictory. As they contend in productive tension, they threaten a spiraling descent into authoritarianism and deepening capitalist retrogression.

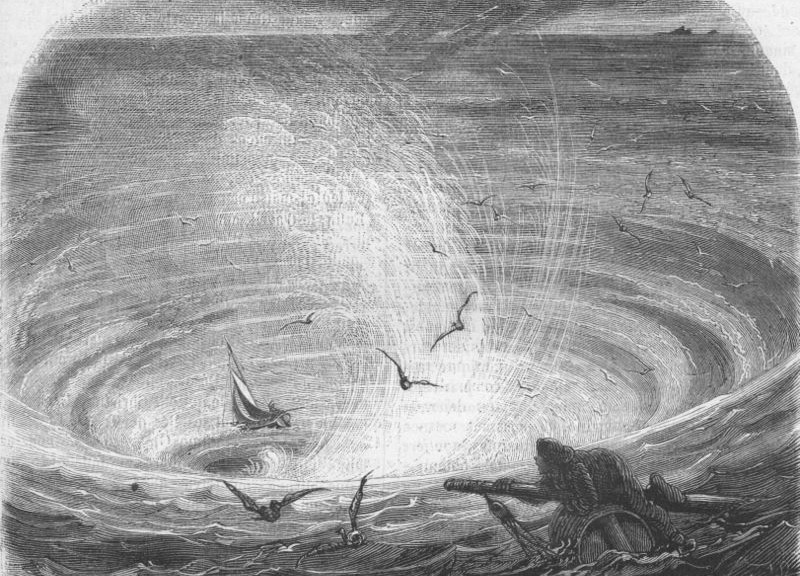

Trump’s election signals that the turbulent waters of social contradiction have begun to spin faster. To grasp the dangers of this dynamic and how to overcome them, we have to trace their emergence from our own history, starting with the current capitalist crisis.

A New Hegemony from the Wreckage

In the late 1970s the U.S. capitalist class faced economic stagnation, rising inflation, and working class revolt in the streets and on the assembly line. In a bid to renew investment, they turned to attacking the costs of labor power, creating a new kind of working class in the process and detonating the Keynesian consensus that had stood for forty years. The 1970s crisis did not lead – as many had hoped – to a revolutionary challenge to capitalism, but to the emergence of a conservative hegemony that would expand and deepen for four decades.

Since the Great Depression, the trade unions, and later the civil rights leadership, has been steadily incorporated into capitalist production and the state. In exchange for labor peace and increased productivity, they were promised expanded democratic rights, racial integration into civil society, and rising real wages. This period marked the definitive transition to the real domination of capital: the incorporation and reorganization of the whole of society according to the needs of capitalist value production. It resulted in a reduction of labor power, not only in terms of the gap between wage levels and the immense surpluses created at the time, but also through labor’s subjugation as an appendage of automation and the remaking of everyday life. The gap between the condition of workers and the enormous productive forces of capitalism continued to widen, sharpening a key contradiction of capitalism. Living standards in the postwar period rose for many layers of the working class, thanks to the growing number of cheap consumer goods. But this trend could only continue as long as the worker generated surpluses rose even faster. With economic stagnation in the 1970s–a combination of falling growth and soaring inflation–the material basis for the Keynesian regime dissolved. The capitalist class had to find a new way to rule.

Continue reading Morbid Symptoms: The Downward Spiral