March 30, 2005

Ridicule is nothing to be scared of

|  |

The ridiculous is not the opposite of the sublime, but its twin. The real opposite of the sublime is, of course, the intransigently banal and commonsensical.

Smug detachment is the required postmodern pose, because, on a psychological level, postmodernism is driven above all by the fear of looking silly, of being seen to be taking something - which the big Other might turn out to deem as ridiculous - seriously. The pomonaut is so depressively flat because he is well aware that there is nothing that can in principle escape this judgement. Conspicuously cultivated ironic distantiation, the flaunting of lack of commitment, is thus the only possible option. (Which is why Luke was right to celebrate Brian Sewell and Tim Westwood a while back, since they are quite the opposite: people who have the courage to be committed, no matter how silly they may be considered by others.)

One of the great things about Russell T Davies is his precisely his willingness to risk ridicule. His treatments of Casanova and Dr Who have shown that it is possible to be serious without being po-faced, and humorous without being pomo-faced. Davies has the courage to be both queer (rather than gay) and a geek. There is a particularly strong relationship between camp and postmodernity, just as there is an affinity between glam and queer. Postmodern camp takes refuge in neurotic hedonism as the safest of all options (no one is going to mock you for pursuing pleasure, surely). Glam, on the other hand, risks taking - itself and 'things' - too seriously. You might find yourself on endless re-run on future editions of I Heart 2005, being mocked by the likes of Paul Ross. But postmodern camp has a vampiric relationship to the ridiculous - whilst viciously ensuring that the cultural and psychological conditions obtain which mean that there can be nothing new produced which might, possibly, be thought of as ridiculous - it nevertheless is in a parasitic relationship to previous forms of the ridiculous. The familiar strategy of raised eyebrows and quotation marks are the means by which the camp pomonaut can live out this bad faith, endlessly lip synching to Abba whilst laughing off stage any contemporary band that displayed their daring ingenuousness.

The political question concerns what escapes ridicule. This occurred to me while flicking through a newspaper in one of our local Eurabian cafes (Eurabian cafes being the superior alternative to American franchise coffee bars round here, of course - I for one would rather live in Eurabia than Gilead). I'd just read the Dr Who reviews, which, like most reviews, are depressing even when they are positive, depressing because they imply that there is this place of neutral uncommitment from which judgement can be passed. The role of a newspaper TV reviewer (leaving Charlie Brooker out of this for the moment) is now to be a mouthpiece for the big Other: there is so much 'contextualization', i.e. conjectures as to what the big O might possibly think, before the judgement is timorously passed. I read only two Dr Who reviews, and both reviewers bent over backwards to establish that IN NO WAY could they be conceived of as Dr Who fans, never watched it before, good god, no, even as children they messy-haired faux-self-deprecating meeja gunslingers in waiting....

But it was the contrast between the grudging, yes, it's a little bit ridiculous but we can allow it throughnow reception of Dr Who and this column that struck me. (btw Can there really be an advertising journalist really called 'Wnek' who is not the invention of Chris Morris?) In some ways, it is unfair to pick on one column; it is not as if this is more absurd than anything else in the media-on-media genre (the lowest, the absolute lowest, circle of hell is occupied by media-on-media journalists). But the point is, how are we in a world where a sentence such as 'when WCRS won the £22m Abbey pitch against incumbent TBWA and the agency I thought would walk it, the resurgent Lowe London' does not only invite corruscating ridicule but also rage?

In many ways, one of the most disappointing things about Nathan Barley was that it - deliberately - missed the opportunity to ridicule that world. Morris and Brooker were so keen to avoid the 'Hoxton satire' label that, for all its strengths, Barley will never rank with Morris' other achievements. In an email interview with the Sunday Times this week, Morris attempted to position Barley as a 'sitcom' as opposed to a 'satire':

"A sitcom isn't usually the right tool for satire ... When you watched I'm Alan Partridge, did you really go, 'Thank God they're exploding the hideous world of the local-radio DJ in temporary accommodation'? Or The Office, 'At last someone's rodding the paper merchants!'"

It's not that there isn't any truth in Morris' remarks. You only have to remember the appalling 'award-winning' Drop the Dead Donkey (the only description more delibidinizing than 'award-winning' being 'based on a true story' of course) to recognize that.

But it is the focus on I'm Alan Partridge rather than Knowing Me, Knowing You that is so telling. As Sphaleotas has argued, I'm Alan Partridge was conservative precisely because it was no longer about the structures of light entertainment but the pathological proclivities of a middle-aged man.

On the other hand, it is not as if The Office WAS purely about Brent's pathologies. On the contrary, the show really started to lose it when it did become solely about Brent's absurdities. As soon as the smugoisie 'Good Manager' - who really CAN good humouredly get along with the staff and 'let his hair down' (but only, naturally, at 'appropriate' times) - arrived from Swindon, the series lost all its bite. It then implied that Friendly Managerialism wasn't innately pernicious and that it is individuals, not the structure of management itself, that are the problem.

Similarly, the problem with Nathan Barley is that Barley is too sympathetic, because too obviously ludicrous. This implies that it is possible to be in nu-meeja/advertising/branding without being infected by their inherent stupefying inanity. It is not the desperate-to-please Barley who should be laughed at (precisely because, in the end, he is well aware of the possibility of ridicule), but people who can smugly talk about 22m advertising pitches as if this and the world they belong to, the world of postmodernity in person, is not in fact, the worst of all words, being both ridiculous AND banal.

_________________________________________________________________

While we're on Russell T... if it is true that Eccleston is leaving Dr Who after one series (proof once again of the inherent evil of actors - I can't think of how many actors 'not wanting to be typecast' blighted my childhood - I take the Kubrick view: yr just a machine part, Mr Actor, live with it), please let it be true that the BBC are talking to David Tenant, the lead in Davies' Casanova. Tenant has a lightness that doesn't come naturally to Eccleston and would be excellent - if, that is, he can contain the egocentrism that is the bane of his profession.

March 28, 2005

The new Dr Who - the k-punk verdict

'Dismembered limbs, a severed head, a hand cut off at the wrist, as in a fairy tale of Hauff's, feet which dance by themselves, as in the book by Schaeffer which I mentioned above — all these have something peculiarly uncanny about them, especially when, as in the last instance, they prove capable of independent activity in addition.'

- Freud, 'The Uncanny'

It ought to have been textbook uncanny. The Autons seemed to have been designed with one eye on 1970's commodities (they first appeared in Pertwee's first episode, 'Spearhead from Space' in 1970, which was also the first time the show was broadcast in colour) and one eye on Freud's 1919 essay.*

The reasons why it didn't quite succeed were not specific to the programme. The problems it faces are the afflictions of more of less all contemporary 'quality' British television, which, increasingly and depressingly, seems to take its cues from British film. What made it feel slightly like a commercial for itself is the pace - far too breathless - and the glossy film stock that all quality TV is now required by law to use. Low budgets force innovation - expense so often leads to an unthinking dependence upon defaults.

The most telling example of this is the music. If only Russell T Davies had the courage to return to the original Delia Derbyshire recording of the theme tune: the addition of 'lush' strings only subtracts from the untimely abstract thrill of its alien electro-pulse. But, more than anything else, it is the incidental music that stops the programme feeling as uncanny as it once did. Hectic technopop and Spielberg/ John Williams-style stringfests call up the off-the-peg affective register triggered by the Hollywood Adventure mode. But watch the series in its classic years and you become aware of how extreme the incidental 'music' could be. In 'The Sea Devils', as Nick Gutterbreakz argued a while back, the atonal echoing electronic screams were barely music at all. The comparison with Throbbing Gristle was not at all idle. There is a wider difficulty here, of course. If the original series benefitted from a surrounding popular culture that was vibrant and experimental, the new one is hidebound by a deeply conservative popcultural context.

Eccleston delivered all the intensity you could expect (but you are left with the question: what is the trademark of his Doctor? The classic incarnations could be summed up in a quick phrase - 'cosmic hobo', 'dandy' - but, at the moment, Eccleston seems to be defined negatively: he doesn't look Edwardian nor use RP). At the moment, he, like the series in general, has merely opened up the space for a new Doctor Who - he hasn't convincingly occupied that space. But, given the constraints, the pressure of expectations, the prevailing vampiricist smugemony, creating such a space is an enormous achievement.

(I saw Billie Piper described as 'dressing like she is a member of Girls Aloud', so, naturally, I approve of her. :-) Seriously, though, she brings an accessible glamour and resourcefulness to the part of Rose that makes her modern without being inusfferably 'street smart'. No danger of the Poochie syndrome, here. The point at which she failed to notice that her boyfriend had been replaced by an Auton duplicate was one of several moments of humour that really worked.)

The success of the classic serial depended upon its shameless appropriation and redeployment of concepts and tropes stolen not only from SF (Kneale, Wells) but also Horror (predictably, my favourite era was the Philip Hinchcliffe 'Gothic' era), detective fictions, myth, history... The opening episode was, predictably and understandably, fed almost entirely on the programme's own history. I should add that it did so with a real wit and affection.

Scanshifts and I identified two challenges that the revivified serial must overcome if it is to succeed: fittingly, they concern time and space. If the serial is to persist with one-off, one-episode adventures, it will work much better if it has less ambition about what it can achieve in 45 minutes. Launch and relaunch episodes are always weighed down by too much exposition, which meant that a degree of rushing about was always going to be inevitable. Closer focus on a confined space, with a strongly defined atmosphere, would surely be a better model for future episodes. There are certain things which cannot easily be done in that attenuated time-frame - the slow-building sense that something is amiss, the gradual accretion of anomalous signs, the forming of hypotheses - all of this before the monster(s) appears... that just seems impossible if you only have forty-five minutes.

I'm hoping that, once the new serial can acquire the confidence it deserves, it will have the nerve to break away from the overlit dullness of contemporary British television's obligatory naturalism. Certainly, I'm heartened by the fact that it managed two million more viewers than ITV's Ant and Dec - which featured David Beckham! and Mariah Carey! Maybe - tentacles crossed - the tide is finally turning against celebrealism. Maybe the Britain that Simon evoked yesterday when he talked of a country that was both seedier and stranger than Blair's Mission Statement nation, maybe that Briain is rediscovering itself....

* Dismembered footnote: It should be remembered, though, that Freud goes out of his way to seek to dismiss the idea that ‘doubts whether an apparently animate being is really alive; or conversely, whether a lifeless object might not be in fact animate’ was definitional of the uncanny.

Final note: Russell T Davies' version of the life of Casanova was an unqualifed success, which anyone who didn't see it on BBC Three should make a point of catching when it is broadcast on one of the terrestrial channels. Costume drama that looks like it is modelled on Adam and the Ants videos... Clothes that owe more to Leigh Bowery than to the historical record... Dance scenes that fly from even the pretence of naturalism to attain an oneiric expressionism.... A lead who manages, somehow, to find the diagonal between the Scylla (Lad) and Charybdis (Camp) of contemporary masculinity ... Yes, it really did happen... (And that's not even mentioning Peter O'Toole in a marvellous performance as the dying roué).

March 25, 2005

Lions after slumber, or What is sublimation today?

'In post-liberal societies ... the agency of social repression no longer acts in the guise of an internalized Law or Prohibition that requires renunciation or self-control; instead, it assumes the form of a hypnotic agency that imposes the attitude of "yielding to temptation" - that is to say, its injunction amounts to a command: "Enjoy yourself!" Such an idiotic enjoyment is dictated by the social environment which includes the Anglo-Saxon psychoanalyst whose main goal is to render the patient capable of "normal", "healthy" pleasures. Society requires us to fall asleep into a hypnotic trance...'

- Zizek, 'The Deadlock of Repressive Desublimation', in The Metastases of Enjoyment, 16

As we awake from the dreary dream of entryism, we can start to see that what kept us slumbering in the last twenty five years was indeed a programme of controlled, if not quite repressive, desublimation.

No doubt, the signs of any awakening are fitful as yet. In pop, they are perhaps most evident in a groping backwards, a paradoxical return to modernism. Could it be that the likes of Franz Ferdinand and The Rapture will prompt a self-overcoming of the very postmodern revivalism of which they are a symptom? Just now, Rip it up and Start Again sounds like a uncannily timely injunction.

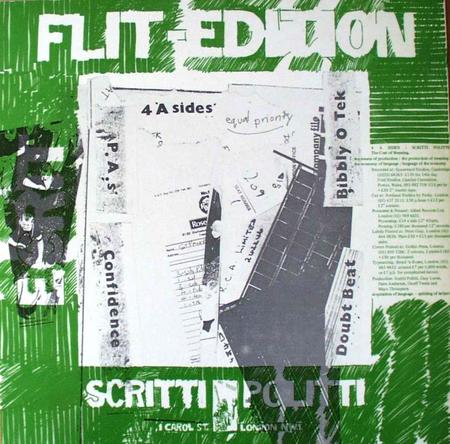

Something seems to be (re)coalescing, as the reception of the Early Scritti LP (including Simon's piece in Uncut) indicates.

For those Inside - not least, of course, Green himself - these recordings must be dismissed as inept avant-doodlings, embarrassing juvenilia. It seems plausible to attribute Green's less-than-lukewarm judgements on the early Scritti material less to modesty, still less to a 'maturity', than to a defensive cleaving to a once-successful strategy that has now run its course, as Marcello acidly noted in his acerbic comparison between the indifferent reception of the last Scritti album and the eagerness with which Early has been anticipated :'when you next find yourself at a motorway service station, feel free to browse through the plentiful copies of his 1999 up-to-the-1999-minute-Mos-Def-involving Anomie and Bonhomie album, yours for just £1.99 - whereas the new collection of his scratchy, disjointed post-punk improv stuff from two decades ago reportedly already has 10,000 advance orders.'

Scritti were the most successful - aesthetically, commercially - of the post-post-punk entryists (the likes of U2 being always-already included of course). In the desolate gloss of mid-late 80s pop, Scritti's hyper-saccharine sweetness retained a plaintive if sickly gorgeousness, even if their vaunted deconstructive swerves became subtle to the point of invisibility. But the fastidious precision of that striplit eighties production has dated (late eighties chartpop is the most time-bound pop music ever - discuss) much more damagingly than has the messthetic of the early records. Whereas the conspicuous completeness of Eighties Entryist Pop repels fascination, the queasy, uneasy Unfinishedness of postpunk pop - the lurching 'doubtbeat' of a collectivity discovering itself - is uncannily compulsive. In punk cut and paste, the joins, the cuts (in other words the ways in which any world does not coincide with itself) are flaunted and foregrounded. Entryism is the capture of cut and paste into photoshopped seamlessness.

What is perforce lost in today's postpunk revivalists is the literal in-tensity of this sound: how it is in Kierkegaard-Zizek's terms, in becoming. It doesn't know anything (it certainly can't be confident that it is a 'classic independent rock sound' in the way that Franz Ferdinand are). In flight from rock's 'condition of possibility', this undo (it) yourself pop puts into question ALL conditions of possibility, and with them the very concept of conditions of possibility. What is this if not the sound of the Badiou Event, which is the punk revelation itself: this is happening, now, but it can't be, it's Impossible....? ...

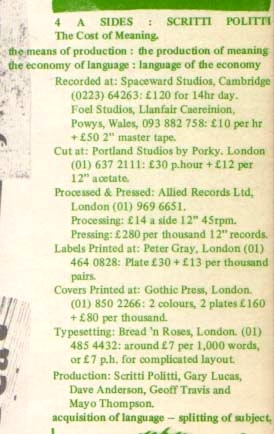

Scritti were possibly the least Dionysian pop group ever. In the early days, the methodology may have been improvisational, but the group didn't want anyone (least of all themselves) to be under the illusion that it issued from some vitalist wellspring of creativity. It was the sound of a collectivity thinking (itself into existence) under and through material constraints. The famous displaying of all the recording costs on the sleeve was demystificatory but not desublimating. What is too often missed about any punk that matters in fact, is that sublimation, far from requiring mystification, is alien to it.

As Alenka Zupancic argues, mysification is entirely on the side of the reality principle (and one of the greatest contributions psychoanalysis has made to politics is to identify 'realism' precisely with a reality principle, so that what counts as 'commonsense' can be exposed as an ideological determination):

'The important thing to point out ... is that the reality principle is not some kind of natural way associated with how things are, to which sublimation would oppose itself in the name of some Idea. The reality principle itself is ideologically mediated; one could even claim that it constitutes the highest form of ideology, the ideology that presents itself as empirical fact (or biological, economic...) necessity (and that we tend to perceive as nonideological). It is precisely here that we should be most alert to the functioning of ideology.' (The Shortest Shadow, 77)

Listen to what Marcello calls the 'pseudo-moronic chants of platitudes ("An honest day's pay for an honest day's work! You can't change human nature! Don't bite the hand that feeds!"' of Scritti's 'Hegemony' and it is clear that this message has got through. It is the denunciation and exposure of the great ideological swindles that are liable to be remembered about punk, but this destructive urge (passive nihilsm) is empty without its active complement: the production of a new space. It is no accident that mystificatory realism has allowed us to remember the former but not the latter, since the mere dismantling of ideological presuppositions quickly became a dreary academic parlour game associated with a dessicated, depressive and depressing Left (they want to take your enjoyment away from you....)

Zupancic labels the production of this new space 'sublimation'. To understand why this she makes this move entails differentiating sublimation from the sublime as such. The postmodern emphasis on sublimity has tended to stress the sublime as an unreachable beyond, contemplation of which induces a pathos of finitude in any human subject. To think about sublimation, the process by which an object 'acquires the dignity of the Thing', produces a different emphasis. As Zupancic continues:

'the Lacanian theory of sublimation does not suggest that that sublimation turns away from the Real in the name of some Idea; rather, it suggests that sublimation gets closer to the Real than the reality principle does. It aims at the Real precisely at the point where the Real cannot be reduced to reality. One could say that sublimation opposes itself to reality, or turns away from it, precisely in the name of the Real. To raise an object to the dignity of the Thing is not to idealize it, but rather to "realize" it, that is, to make it function as a stand-in for the Real.'

Sublimation is thus related to ethics insofar as it is not entirely subordinated to the reality principle, but liberates or creates a space from which it is possible to attribute certain values to something other than the recognized and established "common good." ... What is at stake is not the act of replacing one "good" (or one value) with the same planetary system of the reality principle. The creative act of sublimation is not only a creation of some new good, but also (and principally) the creation and maintenance of a certain space for objects that have no place in the given, extant reality, objects that are considered "impossible."'

What was the 'beyond good and evil' of Scritti, Gang of Four, the Pop Group and the Raincoats if not the production of just such a space? (As Lacan wryly notes, when we idly think of someone who is 'beyond good and evil' we are liable to think of someone is merely beyond 'good'.) This entails not an austere asceticism but the engineering of new forms of enjoyment. The early Scritti's 'difficulty' places them beyond the pleasure principle, for sure, but we succumb to an ideological lure if we think that this puts them beyond enjoyment too. As Savonarola said to me a few weeks ago, Gang of Four were far more effective at turning out compulsive pop songs than almost any of today's chart act you could care to name. The same goes double for Early, whose songs are catchy because they refuse to push familiar buttons.

Entryism constitutes a double disavowal of sublime space. First, it is turned away from, then the very possibility of its existence is denied. In retrospect, entryism has to seen as the production of a particularly virulent capitalist mind plague. How else to acount for the absurd convolutions that allowed Green to posit some political continuity between the avant-Marxism of the early years and the champagne-swigging meta-boyband-cum-yuppie-corporation 'hammer and popsicle' posturing (check some of those pics which illustrate Simon's piece) of the chart Scritti? As Simon has shown elsewhere, Green had by this point done more than merely accommodated himself to the market; he was acting as an entrepraneur, since the 'Fairlight future-funk' of Cupid and Psyche 85 was so far ahead of the game it actually influenced black pop.' There's a case for saying that Cupid and Psyche's 'dazzling, depthless surfaces' in which '"soul" and interiority are abolished' and 'desire traverses a flat plane, the endless chain of signifiers, the lover's discourse as lexical maze' was THE sound of eighties capital, the perfect soundtrack to Jameson's Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, what if felt like to be lost in the mirrored plateaux of the hypermarket.

Realism always poses as maturation. Of course it is acceptable, understandable and inevitable to have silly youthful dreams, but there comes a time when one must put aside such childish things and face reality; and reality is always defined 'biologically', in terms of the imperatives of reproductive futurism, and 'economically', in terms of the 'constraints' of the capitalist anti-market.

Readers of the lamented but never forgotten Pillbox may remember a letter Penman received from Brian Anderson of the neo-Conservative City Journal. Anderson's account of the intellectual provenance of neo-conservatism - many neo-cons were tellingly described as disappointed, disillusioned leftists who had been 'mugged by reality' - concluded with the following convergence between New Pop entryism and his own neo-conservative turn:

'Also - and this will probably horrify you-my move right came partly thanks to Ian Penman and Paul Morley at NME! Your rejection of overly politicized agitprop in music back in the late seventies made intuitive sense to me - I disliked the didacticism of Billy Bragg or Crass, and could stomach even less the critics who pretended to be revolutionaries, etc. There was far more truth in an August Darnell ballad, I came to believe, than in the entire socialist posturing of, say, the Gang of Four or Robert Christgau.'

There it is: THAT opposition - Bragg versus Darnell - was the problem of the mid to late eighties. As soon as it was a question of dour meat and potatoes no fuss empiricism (Left) versus bright and brash hedonism (Right), there was no longer any real choice. The sublime had been extirpated, and what remained was a quotidian cavilling against the wipe-clean sheen of the mall.

It's telling that Scritti's 'Confidence' ('Outside the clubs of boyhood/Inside monogamy') should be so preoccupied with the problems of 'being a man', and what that entailed.

The interpellated subject of the Lad magazine is the supposed 'real person' (=slavering, sloppy andro-Id) beneath the pretence of social politesse. The Lad magazine addresses this 'authentic id' with the leering superegoic injunction to enjoy. 'Go on, admit it, you don't want to be bothered to cook, all you want is a fishfinger sandwich... Go on, admit it, you don't want to be bothered to talk to a woman, have a wank instead...' The fact that this reduction is possible means that Lads implicitly accept the Lacanian notion that phallic jouissance involves masturbation with a 'real' partner. It also indicates that Laddishness is more defined by a propensity towards depressive indolence than it is by any lasciviousness. What Laddism attempts is a short-circuiting of desire (yes, I know that the 'inhuman partner' of desire cannot be attained, just give me pictures of girls next door instead).

From 'Skank Bloc Bologna' ('an imaginary network of dissidents stretching from Jamaica to Bologna's anarchist squatters') to The Streets (Lads of the world unite to raise a glass to lachrymose lariness); from 'The "Sweetest Girl"' to Abi Titmuss...

Long past time that we roused from this slumber... Especially when, with habeas corpus suspended and mainstream political parties all but burning down gipsy camps, one of the things that makes the early Scritti so contemporary is that their conjecture/ fear that It (fascism) Would Happen Here, their 'très 1979 paranoia', is suddenly, alarmingly très 2005.

'Rise, like lions after slumber,

In unvanquishable number,

Shake your chains to earth like dew,

Which in sleep had fall'n on you.'

March 20, 2005

PLUGS

1. The official listing for the Scanshifts/ k-punk audiomentary londonunderlondon, to be broadcast April 4th. Still in final phase of production, with contributions from Dissensus/ old skool blog massive such as Craner and Evergreen Jim already happening --- Heronbone yet to be induced into recording his txt, but I've not given up hope.

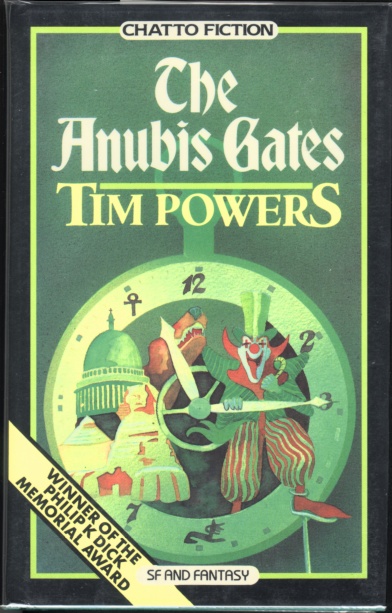

2. (Related to the above, since I re-read the book as part of the research for LuL). Me on Tim Powers' The Anubis Gates and closed loop time paradoxes at Hyperstition.

I first read about The Anubis Gates in Stephen Jones' and Kim Newman's delightfully compendious Horror: 100 Best Books. (This was also where I first heard tell of another hyperstitional classic, Robert Holdstock's Mythago Wood). The entry on The Anubis Gates was written by the brilliant science fiction critic John Clute, who rightly saw The Anubis Gates as profoundly Dickensian. '[T]he Gothic fever-dreams of such writers as Monk Lewis or Charles Maturin can be seen to underpin the oneiric inscapes of the greatest achievements of Dickens - Bleak House (1852-3) or Little Dorrit (1855-7) or Our Mutual Friend (1865) - these novels in which the nightmare of London attains lasting and definitive and horrific form. For Dickens, that nightmare of London may be a prophetic vision of humanity knotted into the subterranean entrails of the city machine, while for Powers the London of 1810 may be a form of nostalgia, a dream theatre for the elect to star in, buskined and immune; but at the heart of both writers' work glow the lineaments of the last world city.' All the sentimental overcodes hymning hearth and home cannot conceal the fact that the libidinal motor of Dickens steam pulp engine is the energy and topology of the pack-rhizome. The happy endings in which the street urchins are esconced into the warm glow of sedentary familality are always disappointing but libidinally unconvincing, terminations of the populations and movements which sustain the novels' desiring-plateaus. Scanshifts tells me that Dickens was crestfallen when he went to Zurich because the city wasn't big enough to contain his walks: all too soon, he would find himself out in the country.

One glorious moment I didn't mention in the Hypersition piece is Powers' joke at the expense of Coleridge (and by extension the whole Romantic cult of the creative imagination). Towards the climax of the book, Coleridge is abducted and imprisoned in the catacombs presided over by the beggar king-sorcerer-clown Horrabin. Horrabin's magic seems to involve an element of Frankensteinian-Moreauesque slash and paste ('the clown's opened up the Hospital' is one of the most terrifying lines in the book), and the lower levels of his subterranean kingdom are filled with shambling, chittering sorcerous-surgical monstrosities that the appalled beggar minions refer to as 'Orrabin's Mistakes. Coleridge, who has been drugged with laudanum (Horrabin's henchmen not suspecting that he is an addict have under-dosed the old poet) wanders amid the Boschian Londerworld, convinced that the loathsome apparitions are aspects of his own mind. The step from the 'creative efflorescence' of the Romantic Imagination to platitudes beloved of delibidinizers everywhere (hey, the heart of darkness is the darkness WITHIN US) is really very short.

btw: was reading The Anubis Gates on the train from Hampton Court to Shepperton whilst on a method writing tour of South London for LuL a couple of weeks ago when the train guard saw it and said, 'That's the best book ever written...'

3. An intereting newish blog cPROBES (Zizek, Baudrillard, McLuhan...) which also has a Lacan/Zizek glossary and a handy page of Baudrillard links.

March 13, 2005

This movie doesn't move me

As I nervously anticipate the new Doctor Who (although after McCoy, after McGann, what more than there to be fear?) , it is worth thinking again about the appeal of the series, and also, more generally, about the unique importance of what I will call 'uncanny fiction'.

A piece by Rachel Cooke in the Observer two weeks ago brought these questions into sharp relief. Cooke's article was more than an account of a television series; it was a story about the way broadcasting, family, and the uncanny were webbed together through Doctor Who. Cooke writes powerfully about how her family's watching of the programme was literally ritualized: she had to be on the sofa, hair washed, before the continuity announcer even said the words, 'And now....' She understands that, at its best, Dr Who's appeal consisted in the charge of the uncanny - the strangely familiar, the familiar estranged: cybermen on the steps of St Pauls, yeti at Goodge Street (a place whose name will forever be associated with the Troughton adventure, 'The Web of Fear', for Scanshifts, who saw it whilst living in New Zealand).

Inevitably, however, she ends the piece on a melancholy note.

Cooke has been to a screening of the first episode of the new series. She enjoys its expensive production values, its ‘sinister moments’, its use of the Millennium Wheel. ‘But it is not – how shall I put this? - Doctor Who.’ Faced with an ‘overwhelming sense of loss’, she turns to a DVD of the Baker story Robots of Death for a taste of the ‘real’ stuff, the authentic experience that the new series cannot provide. But this proves, if anything, to be even more of a disappointment. ‘How slow the whole thing seems, and how silly the robots look in their Camilla Parker-Bowles-style green quilted jackets. … Good grief.’

Let's leave aside, for a moment, all the post-post-structuralist questions about the ontological status of the text 'itself', and consider the glum anecdote with which the article concludes: ‘Before Christmas, when it became clear that my father’s cancer was in its final stages, my brother went out and bought a DVD for us all to watch together. Dad was too ill, and box went unopened. At the time, I cried about this; yet another injustice. Now I know better. Some things in life can’t ever be retrieved – an enjoyment of green robots in sequins and pedal pushers being one of them.’

This narrative of disillusionment belongs to a genre that has become familiar: the postmodern parable. To look at the old Dr Who is not only to fail to recover a lost moment; it is to discover, with a deflating quotidian horror, that this moment never existed in the first place. An experience of awe and wonder dissolves into a pile of dressing up clothes and cheap special effects. The postmodernist is then left with two options: disavowal of the enthusiasm, i.e. what is called 'growing up', or else keeping faith with it, i.e. what is called 'not growing up'. Two fates, therefore, await the no longer media-mesmerised child: depressive realism or geek fanaticism.

The intensity (with) which Cooke invested in Doctor Who is typical of so many of us who grew up in the sixties and seventies. I, slightly younger than her, remember a time when those twenty-five minutes were indeed the most sacralised of the week. Scanshifts, slightly older than me, remembers a period when he didn’t have a functioning television at home, so he would watch the new episode furtively at a department store in Christchurch, silently at first, until, delighted, he found the means of increasing the volume.

The most obvious explanation for such fervour - childhood enthusiasm and naivete - can also be supplemented by thinking of the specific technological and cultural conditions that obtained then. Freud's analysis of the 'unheimlich', the 'unhomely', is very well known, but it is worth linking his account of the uncanniness of the domestic to television. Television was itself both familar and alien, and a series which was about the alien in the familiar was bound to have particularly easy route to the child's unconscious. In a time of cultural rationing, of modernist broadcasting, a time, that is, in which there were no endless reruns, no VCRs, the programmes had a precious evanescence. They were translated into memory and dream at the very moment they were being seen for the first time. This is quite different from the instant – and increasingly pre-emptive - monumentalization of postmodern media productions through ‘makings of’ documentaries and interviews. So many of these productions enjoy the odd fate of being stillborn into perfect archivization, forgotten by the culture while immaculately memorialised by the technology.

But were the conditions for Dr Who's colonizing presence in the unconscious of a generation merely scarcity and the ‘innocence’ of a ‘less sophisticated’ time? Does its magic, as Cooke implies, crumble like a vampire seducer in bright sunlight when exposed to the unbeguiled, unforgiving eyes of the adult?

According to Freud’s famous arguments in ‘Totem and Taboo’ and ‘The Uncanny’, we moderns recapitulate in our individual psychological development the ‘progress’ from narcissistic animism to the reality principle undergone by the species as a whole. Children, like 'savages', remain at the level of narcissistic auto-eroticism, subject to the animistic delusion that their thoughts are ‘omnipotent’; that what they think can directly affect the world.

But is it the case that children ever ‘really believed’ in Doctor Who? Zizek has pointed out that when people from 'primitive' societies are asked about their myths, their response is actually indirect. They say ‘some people believe….’ Belief is always the belief of the other. In any case, what adults and moderns have lost is not the capacity to uncritically believe, but the art of using the series as triggers for producing inhabitable fictional playzones.

The model for such practices is the Perky Pat layouts in Philip K Dick’s Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch. Homesick offworld colonists are able to project themselves into Ken and Barbie-like dolls who inhabit a mock-up of the earthly environment. But in order to occupy this set they need a drug. In effect, all the drug does is restore in the adult what comes easily to a child: the ability not to believe, but to act in spite of the lack of belief.

In a sense, though, to say this is already going too far. It implies that adults really have given up a narcissistic fantasy and adjusted to the harsh banality of the disenchanted-empirical. In fact, all they have done is substituted one fantasy for another. The point is that to be an adult in consumer capitalism IS to occupy the Perky Pat world of drably bright soap opera domesticity. What is eliminated in the mediocre melodrama we are invited to call adult reality is not fantasy, but the uncanny - the sense that all is not as it seems, that the kitchen-sink everyday is a front for the machinations of parasites and alien forces which either possess, control or have designs upon us. In other words, the suppressed wisdom of uncanny fiction is that it is THIS world, the world of liberal-capitalist commonsense, that is a stage set with wobbly walls. As Scanshifts and I hope to demonstrate in our upcoming audiomentary london under london on Resonance FM, the Real of the London Underground is better described by pulp and modernism (which in any case have a suitably uncanny complicity) than by postmodern drearealism. Everyone knows that, once the wafer-thin veneer of 'persons' is stripped away, the population on the Tube are zombies under the control of sinister extra-terrestrial corporations.

The rise of Fantasy as a genre over the last twenty-five years can be directly correlative with the collapse of any effective alternative reality structure outside capitalism in the same period. Watching something like Star Wars, you immediately think two things. Its fictional world is BOTH impossibly remote, too far-distant to care about, AND too much like this world, too similar to our own to be fascinated by. If the uncanny is about an irreducible anomalousness in anything that comes to count as the familiar, then Fantasy is about the production of a seamless world in which all the gaps have been monofilled. It is no accident that the rise of Fantasy has gone alongside the development of digital FX. The curious hollowness and depthlessness of CGI arises not from any failure of fidelity, but, quite the opposite, from its photoshopping out of the Discrepant as such.

The Fantasy structure of Family, Nation and Heroism thus functions, not in any sense as a representation, false or otherwise, but as a model to live up to. The inevitable failure of our own lives to match up to the digital Ideal is one of the motors of capitalism's worker-consumer passivity, the docile pursuit of what will always be elusive, a world free of fissures and discontinuities. And you only have to read one of Mark Steyn's preppy phallic fables (which need to be ranked alongside the mummy's boystories of someone like Robert E Howard) to see how Fantasy's pathetically imbelic manichean oppositions between Good and Evil, Us and (a foreign, contagious) Them are effective on the largest possible geopolitical stage.

March 08, 2005

What are the politics of boredom? (Ballard 2003 remix)

'Prosperous suburbia was one of the end states of history. Once achieved, only plague, flood, or nuclear war could threaten its grip.' (Ballard, Millennium People, 91)

'J.G. Ballard' is the name of a repetition.

That's very different from saying that Ballard repeats himself. On the contrary, it is Ballard's formalism, his repermuation of the same few concepts and fixations - disasters, pilots, random violence, mediatization, the total colonization of the unconscious by images - that prevent his name being easily attributed to any self.

The obsessive quality of his preoccupations and his methodology is a sign that Ballard has never lost faith with his earliest inspirations: psychoanalysis and surrealism. In both, he found a rigorously depersonalized account of the formations of the person. The so-called interior had a logic that could be both exposed and externalised.

Ballard's career can be seen as a repeated rewriting of two texts of Freud, 'Civilization and Discontents' and 'Beyond the Pleasure Principle'. The environmental catastrophes in his earliest phase of novels (The Drowned World, The Drought, The Crystal World) tend to be greeted by the characters as opportunities, chances to shuck off the dull routines and protocols of sedentary society. The second phase of his work, which began in the mid-Sixties and to some extent continues to this day, follows this logic through so that the catastrophes and atrocities that afflict the characters in these fictions are actively willed by them. (Or is it that the humans seek to manage, through repetition, the originary trauma of their being?) Disasters are now the disasters of the media landscape - the space in which humans now primarily live, and one which is both shaped by, and manufactured from, their desires and drives. Once again, though, we must qualify this claim with the further observation that human beings are not the 'owners' of desires and drives - they don't 'have' them. Rather, human beings are the playing out of these impulses, instruments through which trauma is registered.

Since High Rise in 1975, Ballard has directed most of his attention to the hyper-affluent and bored denizens of closed communities. If Ballard's treatment of the mores of this population had begun to pall, it was refreshed by Millennium People, his latest and best rendition of this theme.

The world of Millennium People is ruled, 'for the first time in history' (but not for the first time in Ballard's work), by a 'vicious boredom' 'interrupted by meaningless acts of violence'. At first glance, the novel can look like a long overdue savaging of the middle class, in which the reader can revel in the brutal destruction of bourgeois sacred cows. Tate Modern... Pret-a-manger.... the NFT... all of them burn in Ballard's Bourgeois Terror.

'I'm a fund raiser for the Royal Academy. It's an easy job. All those CEOS think art is good for their souls.'

'Not so?'

'It rots their brains. Tate Modern, the Royal Academy, the Hayward.... they're Walt Disney for the middle classes.' (61)

The novel's middle class insurgents seem, at first, to be merely the hard done-to whiners whose plaints about the rising expense of child care and school fees and the 'inequity' of too high rents in their not quite luxurious enough appartments are the stuff of endless media columns. 'Believe me, the next revolution is going to be about parking' (66) one character announces, echoing the petrol blockades of four years ago and anticipating the Ikea riots of 2005. Once their discontent is stirred up, however, the goals of this group of former professionals become less specific, less instrumentalist.

Like the Situationists, the insurgents of Ballard's fictional Chelsea Marina want to 'destroy the twentieth century'.

'I thought it was over.'

'It lingers on. It shapes everything we do, the way we think. ... Genocidal wars, half the world destitute, the other half sleepwalking through its own brain-death. We bought its trashy dreams and now we can't wake up.' (63)

Millennium People is in many ways Britain's answer to Fight Club (though, needless to say, the chances of Britain producing MP as a film that would even remotely do the book justice are not even slight - precisely because the British film industry is under the control of the same militantly complacent whingers that it attacks). Like Fight Club, the novel begins with a rage against the bullet-pointed, brand-consulted hyper-conformity of modern professional life, but ends up in surfascism.

The most important figure in this respect is Richard Gould who, like most of Ballard's other characters, is little more than a spokesperson for the author's theories. (Which is fine, of course: we need more 'well-drawn characters' like we need more 'well-wrought sentences'. The UEA Eng Lit mafia are as ripe for immolation as are any of the other cosily depressing targets of Ballard's pyromaniac prose.)

Gould reiterates essentially the same attack on the 'air-conditioned totalitarianism' of contemporary securo-culture that had been essayed by Nietzsche, Mauss, Bataile, dada, surrealism, Situationist theory, Lettrism, Baudrillard and Lyotard. 'We're living in a soft regime prison built by earlier generations of inmates. Somehow we have to break free. The attack on the World Trade Centre in 2001 was a brave attempt to free America from the 20th century. The deaths were tragic, but otherwise it was a meaningless act. And that was its point. Like the attack on the NFT.' (140)

Gould re-states the Nietzschean claim that human beings need cruelty, danger and challenge, but that civilization gives them security. Gould, though, is as reminiscent of Fukuyama's rehearsal of Nietzsche's discontent with civilization as he is of Nietzsche himself.

It is Fukuyama's Nietzsche - the scourge of bland egalitarianism and empty inclusiveness - that is the most relevant Nietzsche today. As you read the appalled invective with which Nietzsche blasts the herd-cult of managed security (which is so weak and insipid that it can never utter its real rallying cry: 'long live mediocrity!') you can't help but think of Blair and the Millennium Dome, whose pallid, paradoxically self-deprecatory pomposity contrasts unhappily with the cruel opulence of the monuments erected in Nietzsche's beloved tragic and heroic aristocratic societies.

'Democratic societies,' Fukuyama wrote in The End of Jistory and the Last Man '... tend to promote a belief in the equality of all lifestyles and values. They do not tell their citizens how they should live, or what will make them happy virtuous and great. Instead they cultivate the value of toleration, which becomes the chief virtue in democratic societies. And if men are unable to affirm that any particular way of life is superior to another, they will fall back on the affirmation of life itself, that is, the body, its needs, and fears. While not all souls may be equally virtuous, all bodies can suffer; hence democratic societies will tend to be compassionate and raise to the first order of concern the question of preventing the body from suffering. It is not an accident that people in democratic societies are preoccupied with material gain and live in an economic world devoted to the myriad small needs of the body. According to Nietzsche, the last man has "left the region where it was hard to live, for one needs warmth".' (305)

'We need to pick targets that don't make sense.' (175)

If the characters in The Atrocity Exhibition wanted to restage the founding traumatic of the media 60s - the assassination of Kennedy - then Gould and his allies want to restage the founding traumatic moment of the media 00s- 9/11. But where Traven/Tallis/Travis wanted to kill Kennedy again, 'but this time in a way that makes sense', Gould wants 9/11 to happen again, but in a way that doesn't make sense.

For Gould, the (post)modern world is oppressed by an excess of Sense, a surplus of Meaning. 'Kill a politician and you're tied to the motive that made you pull the trigger. Oswald and Kennedy, Princip and the Archdukes. But kill someone at random, fire a revolver into McDonald's - the universe stands back and holds its breath. Better still, kill fifteen people at random.' (176) Thus, the Jill Dando murder is more of a template for Gould's anti-political insurgency than is September 11th, whose violence was (still) too motivated, too freighted with Meaning. Dando's killing however - brutal, meaningless, and without any apparent motive - was a direct attack on the BBC's 'regime of moderation and good sense' (149) and the 'castle of obligations' (166) it protects. An action like this, whose only motive is an attack on the concept of motive itself, blows open an 'empty space we could stare into with real awe. Senseless, inexplicable, as mysterious as the Grand Canyon.' (249)

Gould is an elegant and eloquent salesman of the Deleuze-Guattari 'line of abolition', the Fascist drive to destruction which is ultimately a drive towards self-destruction. Ballard, who, to his credit has always refused to endorse facile moralizing, would no doubt object to that characterization, since to in any way condemn or censure Gould would be to confirm the very securocratic values he seeks to undermine.

However, the most compelling aspect of Millennium People, politically speaking, is not the in many ways familiar asignifying violence, but its PUNK THEORY OF CLASS REVOLT.

'Twickenham is the Maginot Line of the English class system. If we can break through here, everything will fall.'

'So class systems are the target. Aren't they universal - America, Russia...?'

'Of course. But only here is the class system a means of political control. Its real job isn't to suppress the proles, but to keep the middle classes down, make sure they're docile and subservient.' (85)

The moment at which Ballard's 'new proletariat' ('furnished with private schools and BMWs') become real political actors is when they cease to pursue their own class interests. Only then can they come to the Marxist revelation that bourgeois class interests are in no-one's interests.

'They see that private schools are brainwashing their children into a kind of social docility, turning them into a professional class who will run the show for consumer capitalism.'

'The sinister Mr Bigs?'

'There are no Mr Bigs. The system is self-regulating. It relies on our sense of civic responsibility. Without that society would collapse. In fact, the collapse may even have begun.' (104)

Blairism has consolidated and outstripped the ideological gains of Thatcherism by ensuring the apparently total victory of PR over punk, of politeness over antagonism, of middle class utility over Proletarian art. It manages the tricky ideological dodge of reducing everything to instrumentality whilst AT THE SAME TIME dedicating all resources to the production of cultural artifacts of no possible use or function. From the Mayan codices to Mission Statements.... Spin engenders a Meaninglessness which, in the mandatory banality of its corrosive nihilism, makes Gould's grand poetics of asignifying rupture seem quaintly nostalgic.

Blair has made middle class security the horizon of all aspiration. In this overconscious, overlit 24 hour office of the soul, Business, preposterously, is served up to us as the closest thing to anything animated by libido. Ballard knows that a break out from this affective prison must involve the explicit de-cathexis of the 'nice house, nice family' picture that bourgeois culture is still capable of projecting as ideal.

In histories of punk, much is made of the role of the middle classes, but the crucial catalytic role of that particular kind of middle class refusal remains under-thought. The middle class defection from reproductive futurism into scarification and tribalization did nothing more than state the obvious - middle class careers and the privileges they bring are empty, tedious and ennervating - but, now more than ever, it is this obviousness that cannot be stated.

'The interesting thing is that they're protesting against themselves. There's no enemy out there. They know that they are the enemy.' (109)

March 03, 2005

Family values

|  |  |

Which one is the face of Evil?

Ideology's first task - always, necessarily, accomplished invisibly - is to establish what counts as ideology. That is to say, it operates by naturalizing its own presuppositions and designating opposing political positions as 'merely' 'ideological'. This process is nowhere better exemplified than in the process which Giorgio Agamben, developing, extending and critiquing Foucault, has dedicatedly analysed: the bleeding of the biological-private-domestic into the public-political, i.e. the founding of bio-politics.

In contemporary Britain, the 'working mother' is the figure around which many bio-political configurations are organized. The 'working mother' gives a new spin to the old Hegelian formula, according to which 'woman is the eternal irony of the community'. The idea was that women's labour (in every sense) was essential to the reproduction of the polis, but that women remained outside the community proper, double agents, never fully assimilable into civil society.

Alison Pearson re-stated this position today when she described what the Government has absurdly called 'Sandwich Women' - i.e. working mothers - as 'the filling that holds society together'. They are, then, the filling that holds the community together - but still, it seems, not quite members of that community themselves?

Pearson's comments were prompted by the Government's proposals to extend maternity leave from six to nine months. Now, leaving aside the fact that this means that once again, that non-breeders will have to fund reproductive futurists' lifestyle choices, it is clear that this supposedly 'female-friendly' legislation rests on a number of assumptions, the most pernicious of which is not the belief that the burden of child-care should 'naturally' fall predominantly upon women. No: one of the most dangerous presuppositions is the unargued view that the 'best' (='most natural') way for a child to be reared is in a private domestic space by its female parent.

The language of rights is also double-edged in this respect, as in so many others. The 'right' to have children often seems to operate as a post-feminist way of re-inscribing the female obligation to reproduce. Similarly, the 'right' to maternity leave imposes a social expectation (what kind of a woman, we are invited to think, would not take up maternity leave?)

More than that, though, construing this issue in terms of individual rights distracts from the way in which compelling women to adopt this role makes alternatives to the nuclear family - e.g. collective child rearing by groups of women - both unthinkable and impracticable.

It is, to say the least, by no means self-evident that the best way to rear children is in a domestic space with their mother. I speak as someone whose upbringing was of that type. Being the sole subject of the attentions of a young woman who - as she would now admit - had limited confidence was unlikely to do much for the mental health of either child or parent. A world inhabited almost exclusively by mother and child cannot but be cloyingly, suffocatingly confining: and any security and safety that both experience is inevitably achieved at a high price, namely the coding of the world Outside as a place of uncertainty, fear and loathing. To be brought up partly by 'strangers' and with other children is not only to let some air into the fetid closeted space of the domestic neurosis factory, it is also to go some way to weakening the distinction between what is familiar/ familial and what is 'strange'.

But 'family values', once a matter of stated political doctrine, have now receded from the realm of political contestation to become naturalized. Indeed, a deep commitment to the Family is the closest that contemporary secular Britain will come to a religious conviction.

There is no longer much sense that there could be a meaningful conflict of duties between duties towards one's family and other duties. Much of the castigation of the Queen over her refusal to attend Prince Charles' farce of a wedding has concerned her 'monstrous' rating of her Duty as a monarch and as head of the Church of England over her duties as a mother. Contemporary tabloid wisdom has it that the Queen's 'failings as a mother' make her 'inhuman'. Take, as one example of many, Carole Malone in the Sunday Mirror: 'The fact is that most mothers would die for their children. But one feels that while the queen would happily die for her country, her kids come very low down her list of priorities. And while that makes her a good Queen, it makes her a pretty bad mum and an even worse human being.'

There we have that it then: attaining 'good' human status involves us FIRST OF ALL being committed to our families. But this naturalizing and prioritising of familial obligations, far from being a self-evident ethical Good, in fact means the end of the ethical as such. Ethics and Justice were founded upon the suspension of immediate tribal and animal interests. As Alenka Zupancic has tirelessly insisted, Kant's ethical system, for instance, maintains that the only Ethical acts are those which are undertaken with indifference to one's own ('pathological') interests. So, as the example of the Queen makes clear, obedience to the Moral Law (the empty form of Duty) - particularly in the context of the contemporary bio-political regime - far from producing dumb social compliance, makes people into anti-social 'inhuman' 'monsters'.

In Desperate Housewives at the moment (well, where we are with it in the UK), Bree van de Kamp faces the same 'temptation of the Ethical' in that she has to choose between Justice and loyalty to her son (should she protect him from punishment for his drunk-driving knocking down of Gabrielle's mother-in-law?) To NOT protect him, she is told, would indeed make her a 'monster'.

But the figure of public loathing who is LEAST monstrous according to the current code is Maxine Carr. It was not at all surprising that, in Channel 4's happy-clappy New Age remix of the Decalog (choose your OWN commandment for TODAY!), 'loyalty to Family' should feature. What did Maxine Carr do but act in accordance with that injunction? If it is 'my family right and wrong', then quite obviously one should protect child killers as much as anyone else if they are a member of your family. There is of course no evidence that Carr was aware of Huntley's crimes - on the contrary in fact. But the irrational homicidal loathing to which Carr has been subject presumably has more to do with a violent disavowal prompted by the fact that many are aware that, if they were in Carr's position, they would have behaved exactly as she did.