January 29, 2005

January 26, 2005

KEEP GOING

Quite wonderful passage from Badiou's Ethics which connects up with many things, not least of which the Joy Division post. Here, Badiou isolates the cultural political and psychological machineries which produce and propagate depressive quietism.

Read this and weep about the last twenty five years:

'A crisis of fidelity is always what puts to the test. following the collapse of an image, the sole maxim of consistency (and thus of ethics): 'Keep going!' Keep going even when you have lost the thread, when you no longer feel 'caught up' in the process, when the event itself has become obscure, when its name is lost, or when it seems that it may have been a mistake, if not a simulacrum.

For the well-known existence of simulacra is a powerful stimulus to the crystallization of crises. Opinion tells me (and therefore I tell myself, for I am never outside opinions) that my fidelity may well be terror exerted against myself, and that the fidelity to which I am faithful looks very much like - too much like - this or that certified Evil. It is always a possibility, since the formal characteristics of this Evil (as simulacrum) are exactly those of a truth.

What am I then exposed to is the temptation to betray a truth. Betrayal is not mere renunciation. Unfortunately, one cannot simply 'renounce' a truth. The denial of the Immortal in myself is something quite different from an abandonment, a cessation: I must convince myself that the Immortal in question never existed, and thus rally to opinion's perception of this point - opinion, whose sole purpose, in the service of interests, is precisely this negation. For the Immortal, if I recognize its existence, calls on me to continue; it has the eternal power of the truths that induce it. Consequently, I must betray the becoming-subject in myself, I must become the enemy of the truth whose subject is the 'some-one' that I am (accompanied, perhaps, by others) composed.

This explains why former revolutionaries are obliged to declare that they used to be in error and madness, why a former lover no longer understands why he loved a woman, why a tired scientist comes to misunderstand, and to frustrate through bureaucratic routine, the very development of his own science.' (79-80)

January 23, 2005

Rufige Rummaging

Really lovely of Paul Autonomic to post up scans of my New Statesman Darkside piece from 94. Especially useful since I'd lost track of it.

Simon still persisting in the attempt to posit some kind of epistemological break in my thinking. :-) Think there must still be some misapprehension about what Rationalism involves. It's antithetical to commonsense, not to Dread....

CONTINUOUS CONTACT

Why do I hate talking on the phone, but find MSN messenger so compulsive?

Partly it is because phones are too intrusive. Not because they impose an unwanted intimacy but for exactly the opposite reason. In a typical telephone conversation, you are forced into (re)assuming your assigned social role. Switching out of MSN to talk on a phone is to be forced away from intimacy, back into the Face, back into the established protocols of mammalian interaction. With MSN, however, the ambiguity and novelty of the medium – when using internet messaging, are we speaking or writing? – allows for more slippage. If we tend to say that we will ‘speak’ later on MSN, it is not because we are falling into phonocentrism, but, quite to the contrary, because we are aware that this is a mode of communication which combines speaking with writing, or rather typing (which should not be reduced to writing).

Zizek also provides a clue. In The Fragile Absolute, Zizek illustrates Lacan’s distinction between two types of enjoyment, as outlined by Lacan in Seminar XX: Encore, by referring to male and female uses of the web. ‘On the one hand [heh heh – k-p],’ he writes, ‘we have the closed, ultimately solipsistic, circuit of drives which find their satisfaction in idiotic masturbatory (autoerotic) activity, in the perverse circulating around objet petit a as the object of a drive. On the other hand, there are subjects for whom access to jouissance is much more closely linked to the domain of the Other’s discourse, to how they not so much talk, as are talked about: say, erotic pleasure hinges on the seductive talk of the lover, on the satisfaction provided by speech itself, not just on the act in its stupidity. And does not this contrast explain the long-observed difference in how the sexes relate to cyberspace sex? Men are much more prone to use cyberspace as a masturbatory device for their solitary playing, while women are more prone to participate in chatrooms, using cyberspace for seductive exchanges of speech.’

While men wait for high-resolution webcams which will show everything, women trade words. The fact that both MSN and txting are predominantly used by females is indicative of a more general libidinal difference in how the two sexes have tended to relate to both technology and language.

Some remarks by Irigaray in This Sex Which Is Not One are instructive here, but we have to be careful, since they are capable of misinterpretation if read too quickly. ‘[W]oman’s autoeroticism,’ Irigaray writes, ‘is very different from man’s. In order to touch himself, man needs an instrument: his hand, a woman’s body, language… And this self-caressing requires at least a minimum of activity. As for woman, she touches herself in and of herself without any way to distinguish activity from passivity. Woman “touches” herself all the time, and moreover no-one can forbid her to do so, for her genitals are formed of two lips in continuous contact. Thus, within herself, she is already two – but not divisible into one(s) – that caress each other.’

It is crucial to avoid subsuming what Irigaray is saying here into familiar but inaccurate narratives about women being ‘excluded’ from language. Such a claim would be too easily refuted by a welter of banal empirical observation: the female investment in MSN and txt is only the latest manifestation of an intense female involvement in epistolary technologies. As everyone knows, there was a strong relationship between the epistolary and the novel, both formally and in terms of content (formally, consider the complex implexed epistolary structure of Wuthering Heights, Frankenstein and Dracula; as for content, it is impossible to imagine any of the great literary romances proceeding without letters). And of course, the novel itself began as a Gothic romance, produced by and for women. As Austen’s Northanger Abbey demonstrates, Gothic romances were very precisely a means of women ‘turning each other on’ (and not only sexually). As a propagative erototechnology, the novel was itself a mode of Gothic propagation, the reading of which enabled women to literally – and literarily – enjoy themselves, exploring the spine-chilling thrills that lay beyond the pleasure principle. The scandal, from the POV of patriarchal specularity, was that this enjoyment was both in full view – women would openly read novels in public – but fundamentally inaccessible to the male gaze (what they were doing to themselves could not be seen by men).

No: Irigaray’s point is not about women’s exclusion from language, but about their libidinal incapacity to use it. Men experience themselves as not imbricated in language or technology, but as their users. In fact, and this point is crucial, the assumption of a transcendent, Promethean position in relation to language and technology is what it is to be a man.

All of this is congruent with the cyberotics Sadie Plant began to develop a decade ago.

It’s not only for personal reasons, I think, that I always found Sadie’s Zeros and Ones a disappointing book. It struck me as floaty, imprecise and gestural in a way that the writing that fed into it (‘The Future Looms: Weaving Women and Cybernetics’, ‘Female Touch’, ‘Cyberfeminist Simulations’, ‘Coming Across the Future’) was not. In those early pieces, Sadie developed a lateral connectionist rhizo-writing which challenged the phallic rigor of logos, without lapsing into ‘poetic’ vague-out, by systematically unraveling the rigid pseudo-certainties of patriarchal authority.

Sadie was much more British, much more punk than the precious and ever-so-slightly pompous Donna Haraway. Where Haraway invested in the anti-cybernetic figure of the cyborg, Sadie patched into the anorganic network-weave-matrix of orphan matter. With its invocation of a ‘socialist feminism’, Haraway’s dusty ‘Cyborg Manifesto’ stank of the American liberal academy, whereas Sadie’s work was self-evidently an interface between the academy and its Outside, a line of flight where renegade theorists could commingle with artists, novelists and sonic manipulators. The anti-capitalist pro-market cyber-theory-fiction she and Nick Land innovated in the 90s could only have emerged in Britain. It reminded us that, for all the California-Wired-Hollywood bluster, cyberpunk was essentially a British invention, synthesized first through fictions and sonics then theory.

(As an aside, wasn’t Postpunk in many ways already cyberpunk, the ‘post’ precisely signaling a break with lumpenpunk’s dull r and r orthodoxy? But the ‘cyber’ component of postpunk was not only, or even primiarily, sonic, it was also a matter of the incorporation of anti-biotic fictional viruses into the sonic body. For Magazine, Joy Division, Foxx, the Normal and the Brit-saturated Grace Jones, J.G. Ballard was at least as significant as anything ‘musical’ – his crash ontology was the sonic fictional equivalent of the amen breakbeat in jungle, a kind of consistency-generating semiotic machine.)

One of Sadie’s greatest acts of theoretical viracy was to rescue Irigaray’s work from the tedious swamp of academic representationalism in which it had been mired. When I first saw Sadie speak, to a bunch of idiot-male academic gatekeepers (‘this isn’t Philosophy – get off our land’) at the Philosophy Department in Manchester University, I could almost feel the synapses in my brain reconfiguring as I fell into that vertiginous exhilaration you always feel when conceptual defaults are put to flight – Gibson AND Irigarary, cyberpunk AND French theory… Surely they COULDN’T go together, could they? And yet they MUST…

The line Sadie most frequently cited from Irigaray was this question, from Speculum: ‘If machines, even machines of theory can turn themselves on, cannot women do likewise?’ Cyberfeminism would have to be about women turning themselves on. Whilst there is an obvious auto-erotic dimension to this, it is important not to stop at erotics, but to think about female auto-affection in the most abstract way imaginable. The emphasis was no longer on women seeking representation within the optic of patriarchal spec(tac)ular power. Nor was it about women bragging about their escape from patriarchy’s Videodrome. Both WHAT and HOW men thought were irrelevant to the (un)raveling Cyberfeminist Matrix, which Sadie showed had always been weaving itself, alongside and beneath what patriarchy was screening. Women’s theoretical productions and labour were integral to Spectacular Optical patriarchy, but the reverse was not the case. Women could quite easily get along without men, but men remained pathetically dependent upon females, both fantasmatically and materially.

The suggestive paralleling of women and computers was far more than mere analogy. Sadie pursued the anti-identitarian logic of simulation beyond where maleborn writers such as Deleuze (in Logic of Sense) but more significantly Baudrillard – a theorist Sadie deserves credit for taking seriously at a time when his stocks at an all-time low - were prepared to take it, making possible a kind of post-de Beauvoir existentialist feminism, in which women were Nothing more this process of booting-up without presupposition. Just as computers lacked any assignable essence in that all they were defined only operationally, by their simulation of what other machines (typewriters, calculators, audio and video-players etc.) could do, so women were, in themselves, Nothing: there was no essence of authentic womanhood to be recovered from behind the screens and the simulations. Yet Sadie was able to sidestep the tricksy sophistries consequent upon the Satrean substantialization of Nothing because of her drawing upon the role of zero in digitality and cybernetics. There, zero was not straightforward absence, but an effective virtuality, the baseline from which all intensities are differentiated. Far from being guaranteed by transcendent Unity, the only genuine monism would be a radical abgrund which shattered all identities, all Ones: what the Lyotard of Libdinal Economy called the Great Zero, the unengendered and unnatural Matrix from which all of Nature springs.

On this account, it was suddenly clear that it was men, not women, who were lacking, and always had been. The presence of the phallus – the Master-Signifier, the signifier as such – now marked a disabled body with organ, which was unable, unlike the female body, to turn itself on; the male organism would always require something else to jack into in order to access the depersonalizing matrix of abstract matter, while women, by contrast, could not but be in touch – first of all, with themselves.

So it was possible now to see that patriarchy’s ultimate meta-narrative was itself a story about the meta. The male relationship to the world would always be mediated by tools which he, as the transcendent subject, saw himself as ‘using’. The cyberfeminist assault upon this orthodoxy drew upon two discursive machines which, prima facie couldn’t have looked more male: cybernetics and psychoanalysis.

Cybernetics began as a technics of war. In WWII, it became obvious that human beings alone were not capable of operating at the speed necessary to use weapons like machine guns on aircraft effectively. To optimize their function, the machines would have to be able to reflect on their own performance and produce adjustments: the science of feedback. Hence the paradox of cybernetics, which, precisely in its quest to achieve the final domination of nature by Man ends up reinserting Man into the Matrix of matter. Cybernetics showed that control operated at the level of the circuit, the feedback loop. Such control bore no relation to the transcendent domination that Promethean Master Science once believed it could enjoy. The machine-gunners were not transcendent users of technology, but themselves meat components of a circuit containing both biotic and non-biotic materials.

As for psychoanalysis, its aporia, the void around which the whole discourse unraveled, was the enigma that Freud famously could not resolve, the question ‘What do women want?’ The Irigarayan reverse consisted in deploying the techniques of (the ostensibly) male discipline of psychoanalysis against itself and against the western canon of Master philosophers. Plato’s founding myth of the cave, for instance, was saturated with uterine imagery. From the start, Philosophy would be narrated as an escape from a matter coded as feminine.

The combination of cybernetics with psychonalysis and feminism made possible a writing that would no longer be representational, but productive: an erotic engineering. Crucial here was Gregory Bateson’s post-Wienerian cybernetics of the plateau. The paradox of climax or satisfaction oriented libidinal economies is that they are always haunted by an inbuilt and therefore inevitable dissatisfaction. Everything is geared up to the production of the single moment of alleged ecstasy at orgasm, such that prior to coming, all effort is concentrated into a grim labour while afterwards one is condemned to a tristresse, presaging the diminishing returns repetition of the whole cycle. Almost all of the time, you want to be where you are not. Schopenhauer and Burroughs are among those maleborn speaking animals who have described this grim prison from within its confines.

It is important to recognize that Irigaray’s critique of specularity was not about disparaging looks and looking as opposed to the tactile. There is a tactile gaze whenever looking is not seen, as it is in the phallic libidinal economy, as a substitute for contact.

In the specular economy, everything fulfills a function extrinsic to itself – the images on the screen are there solely because they stimulate the male organ, which in turn must be stroked by the hand. This hand-screen-tool relation is reproduced in the specular-analogue invention of the Mouse, the impetus for the creation of which was men’s unwillingness to learn how to type.

In fact, as both Friedrich Kittler and Nick Land have forcefully shown, the whole male-driven production of the Graphic User Interface (GUI) is a disastrous move for cyberpunk. In early computing – in which, as Sadie has demonstrated, women played innumerable (previously) unsung roles – the relationship between human beings and machines was depersonalizing and dehumanizing. In other words, human beings were sprung out of the representational prison wherein they confuse themselves and their potentials with what the Dominant Operating System tells them they are. With the development of the tellingly named Personal Computer, computers are denumerized and ‘de-abstracted’: your relationship to the machine is conducted via a screen that locks you out of its core functions at the same time as it represents the computer as continuous with the analogue-specular world. You interact with the machine via the eye and the icon. As Kittler glumly notes, with the development of the tellingly named Personal Computer, you are condemned to be a person. This is obvious when you consider that, once, the word ‘computer’, like the word ‘typewriter’, could originally be applied both to the human being ‘using’ – that is to say, involved with – the machine as well as to the machine itself. And it is no accident that most of these typewriters and computers were in the first instance women.

Nick’s invention-discovery of Qwernomics – the schizo-analysis of the impact upon primarily female typists of the arrival of the Qwerty keyboard in the nineteenth century – reinforces this. At the same time as Freud was pioneering his ‘talking cure’ of female hysterics in Vienna, working women in offices were having their unconscious reprocessed through their fingers via keyboard. As their name suggests, the relationship of touch typists to their machines is a tactile, not a specular one: neither the page that is typed upon nor the keyboard need be seen.

Kittler follows McLuhan in tracking a complicity between high modernism and Gothic popular propagation in their focus on the typist (with Eliot, Kafka and Nietzsche – who according to Kittler was the first philosopher to use a typewriter – complemented by Dracula, whose narrative is famously mediated through typewriters and phonographs).

Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch, which seems to have as much to do with Kittler’s Gramophone, Film, Typewriter as Burroughs’ novel, is where these two lines fuse. The incredibly charged scenes between Joan and William Lee are not just mediated by, they are almost entirely conducted through, the typewriter. ‘More erotic…’ Joan moans as they take turns at the keyboard. Perhaps uniquely in contemporary cinema, Cronenberg understands that the erotic is distributed and abstract, not localizable and ‘natural’. Far from being perverse, the typewriter scene in Naked Lunch, like the many machinic sex scenes in Crash correctly shows that the only way for men and women to relate is via a machine – precisely because, no matter how physically close male and female organisms may get, there can be no contact unless the signifying screen is breached, unless, that is to say, the sociobiotic writing machine which assigns sexual roles is itself challenged. In the ‘natural’ way of things – i.e. in the Dominant Operating System’s representation of nature, i.e. the Symbolic Order – there is no sexual relation. There is only masturbation using a woman’s body on the male side (all phallic desire is essentially masturbatory – Lacan) and, if they are very lucky, a wholly different kind of auto-eroticism for the woman. Only by confronting the fantasmatic screen that both separates men and woman and makes such engagement as there is between them possible, only, that is to say, by together rewriting what is already written - the social, biotic and semiotic codes which tell us what we are (Metkoub, it is written: and they don’t want it changed) – only then can there be contact.

Kafka's first letter to Felice: Kittler notes that 33% of the typing mistakes in this letter concerned the personal pronouns "ich" (I) and "Sie" (you). 'Mechanized and materially specific, modern literature disappears in a type of anonymity which bare surnames like "Kafka" or K" only emphasize.'

As Kittler says, word processing engenders a new relation between the sexes:

'Word processing these days is the business of couples who write, instead of sleep, with one another. And if on occasion they do both, they certainly don’t experience romantic love. Only as long as women remained excluded from discursive technologies could they exist as the other of words and printed matter. Typists such as Minnie Tipp, by contrast, laugh at any romanticism. Tha is why the world of dictated, typed literature—that is, modern literature —harbors either Nietzsche’s notion of love or none at all. These are desk couples, two-year-long marriages of convenience, there are even women writers such as Edith Wharton who dictate to men sittirng at a typewriter. Only that typed love letters—as Sherlock Holmes pro and for all in A Case of Identity—aren’t love letters.'

Yet internet messaging and txting make possible a wholly new series of erotic relations even as they restore the original sense of ‘romance’ lost once the term was appropriated by sexualists. Instant Messaging and txt are predisposed towards courtly encounters of roleplay, deferral and ambiguity, in which ambivalence is enjoyed, not (supposedly) extirpated in a meeting of meat which, no matter how brutally physical it becomes, always take place through fantasmatic screens.

But what makes IM and txt different to both the epistolary and the telephonic romance is the question of temporality. With letters, there was always, inevitably, a delay of at least a period of hours; with telephones, by contrast, there is a temporal immediacy which can too easily be confused with an affective immediacy. Phonocentrism is in this sense strictly literal (or should that be, strictly phonic, lol): the here and now presence of the voice is assumed to guarantee an authenticity lacking in keyboard-produced text which always appears after it has been typed (even if only a few seconds). But the delay in IM and txt is what allows us to recognize what we can easily forget when face to face: that we are never speaking to a persona and that all our relations with others are relationships between machines.

January 20, 2005

Simon's interview with CCRU (1998)

(Was talking about this last night with Matt Woebot; it's no longer up on Simon's site, so I think it's time it got another airing. It's definitely a document of a moment in time, of moment in-becoming, and useful background for my Cyberfeminist Redux post, which should be up tomorrow).

RENEGADE ACADEMIA

Simon Reynolds

“CCRU retrochronically triggers itself from October 1995, where it uses Sadie Plant as a screen and Warwick University as a temporary habitat. ...CCRU feeds on graduate students + malfunctioning academic (Nick Land) + independent researchers +.... At degree-O CCRU is the name of a door in the Warwick University Philosphy Department. Here it is now officially said that CCRU ‘does not, has not, and will never exist’.”

—Communique from Cybernetic Culture Research Unit, November 1997.

Still nominally affiliated to the famously poststructuralist Philosophy Department of Warwick University, England, the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit is a rogue unit. It's the academic equivalent of Kurtz: the general in Apocalypse Now who used unorthodox methods to achieve superior results compared with the tradition-bound US military. Blurring the borders between traditional scholarship, cyberpunk sci-fi and music journalism, the CRRU are striving to achieve a kind of nomadic thought that to use the Deleuze & Guattari term—“deterritorializes” itself every which way: theory melded with fiction, philosophy cross-contaminated by natural sciences (neurology, bacteriology, thermodynamics, metallurgy, chaos and complexity theory, connectionism), academic writing that aspires to the future-shock intensity of jungle and other forms of post-rave music.

According to CCRU, its frenzied interdisciplinary activity—as seen in its Virtual Futures and Virotechnology conferences, and its journals ***collapse and Abstract Culture—disturbed Warwick's Philosophy Department, resulting in the termination of the unit. Just as Kurtz disappeared “up river” into the Vietnamese jungle, the CCRU have strategically withdrawn to their operational base in an apartment in nearby Leamington Spa. Institutionally, they've abandoned the university and linked up with renegade autodidacts and para-academic activists like O[rphan] D[frift>], Matt Fuller, and Kodwo Eshun.

CCRU was originally set up as a research unit for cybertheorist Sadie Plant, freshly recruited to Warwick from Birmingham University. With Plant's unexpected departure in early '97 to become a freelance author (the acclaimed cyberfeminist polemic Zeros + Ones, the self-explanatory Writing On Drugs), the role of director of the CCRU was taken over by her ex-lover Nick Land.

Land is the kind of “vortical machine” around which swirl all manner of outlandish and possibly apocryphal stories—allegedly he went through a phase of only talking in numbers, and was once “taken over” by three distinct entities? True or not, there's no denying the fact that, as Lecturer in Continental Philosophy, Dr. Land has been a “strange attractor” luring students to Warwick purely through his personal reputation and charisma. The Thirst For Annihilation: Georges Bataille and Virulent Nihilism, Land's sole book-length publication, is a remarkable if deranged mix of prose-poem, spiritual autobiography and rigorous explication of the implications of Bataille's thought. Prefiguring CCRU's struggles with university bureaucracy, the book drips with anti-academic bile, occasionally spilling over into flagellating self-disgust.

In the early Nineties, Land used to describe himself as a "professor of delirial engineering." After the relatively down-to-earth Sadie Plant's departure, Land has shepherded the CCRU into an uncanny interzone between science and superstition, blending Deleuze & Guattari and Norbert Wiener's cybernetics with his vast knowledge of the occult, chaos magick and parapsychology: the I Ching, Current 93 (Aleister Crowley's kundalini-like energy force), Kabbalist numerology, H.P. Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos, the eschatological cosmology of Terence McKenna, etc.

It's easy to see why Warwick University was consternated by CCRU's research. Explaining one of their numerological diagrams (“an attempt to understand concepts as number systems”), Land describes it as gift from “Professor Barker.” Inspired by Professor Challenger—the Conan-Doyle anti-hero reinvented by Deleuze & Guattari in A Thousand Plateaus:Capitalism & Schizophrenia—Barker appears to be a sort of imaginary mentor who reveals various cosmic secrets to the CCRU. “But we'd be a bit reluctant to say ‘imaginary’ now, wouldn't we?,” cautions Land. “We've learned as much—well, vastly more from Professor Barker—than supposedly ‘real’ pedagogues!” Including Barker's ‘Geo-Cosmic Theory of Trauma’. Following the materialist lead of Deleuze & Guattari, human culture is analyzed as just another set of strata on a geocosmic continuum. From the chemistry of metals to the cycles of capitalism, from the non-linear dynamics of the ocean to the fractalized breakbeat rhythms of jungle, the cosmos is an “unfolding traumascape” governed by self-similar patterns and fundamental processes that recur on every scale.

Libidinising “flows” and investing them with an intrinsically subversive power, Deleuze & Guattari have been criticised as incorrigible Romantics. CCRU develop this element of A Thousand Plateaus into a kind of mystic-materialism. Discussing what CCRU call “Gothic Materialism” (“ferro-vampiric” cultural activity which flirts with the inorganic and walks the “flatline" between life and death), Anna Greenspan talks about how “the core of the earth is made of iron, and blood contains iron,” about how the goal is to “hook up with the Earth's metal plasma core, which is the Body-Without-Organs.” Body-without-Organs (B-w-O) is the Deleuzian utopia, an inchoate flux of deterritorialized energy; Greenspan says they take the B-w-O as “an ethical injunction,” a supreme goal.

* * * *

O[rphan] D[rift>] also talk about “metal in the body” and seeking the B-w-O. Another Land-influenced theory-fiction collective, O[rphan] D[frift>] are CRRU's prime allies: they performed at the CCRU-organised Virtual Futures 96 conference at Warwick, and are set to stage an event in collaboration with CCRU/Switch at London's Beaconsfield Arts Centre, October of this year. Maggie Roberts and Ranu Mukherjee, the core of OD, originally met as Fine Art students at the prestigious-but-conservative Royal College, where their ideas about creating a form of multimedia-based synaesthetic terrorism oriented around “schizoid thinking,” pre-linguistic autistic states and man-machine interfaces proved way too radical. Formed in late 1994, OD was shaped by two mindblowing experiences: “experimentation with drugs and techno,” and a 1993 encounter with Nick Land.

“Before CCRU started at Warwick, Nick latched onto us very intensively for a while,” says Roberts. “We fed him image experience, tactile readings of the stuff he was buried in theoretically. He wanted his writing to kick in a much more experiential way. For us, there was something wonderful about having a man you could ring up and ask: ‘what's radiation?,’ ‘what's a black hole?’”

OD's collective debut was a multimedia installation at London's Cabinet Gallery. What began as a catalogue for the show escalated into an astonishing 437 page book, Cyberpositive. Like Plant's Zeros + Ones, Cyberpositive is a swarm-text of sampled writings that aren't attributed in the text. But where Plant offers footnotes; OD merely list the “asked” and “un-asked” contributors at the end. Published in 1995, Cyberpositive serves as a sort of canon-defining primer for the CCRU intellectual universe, placing SF and cyberpunk writers on the same level as post-structuralist theorists. “We treat Burroughs as clearly as important a thinker as any notional theorist,” says Nick Land, “At the same time, every great philosopher is producing an important fiction. Marx is obviously a science fiction writer.” For her part, Sadie Plant regards the Eighties cyberpunk novelists like Gibson and Cadigan as “more reliable witnesses,” precisely because, unlike theorists, “they don't have an axe to grind.”

The most highly-charged passages in Cyberpositive are the hefty chunks of Plant/Land writing and Roberts's and Mukherjee's evocations of the techno-rave-Ecstasy-LSD experience. “I used to write a lot in clubs, which probably looked really pretentious,” recalls Roberts. “Tracing what's happening in all the different sound channels and what they're doing spatially and physically to you.” The language veers from masochistic mortification of the flesh (“deep hurting techno,” “the meat is learning to know loss”) to imagery influenced by voodoo and shamanic possession (“white darkness,” “the fog of absolute proximity,” “psyclone,” “beautiful fear”). “It's trying to process the dissassembling of the self,” says Roberts. “Maybe what you're calling abject, we'd call melting. The violence of the sounds in techno, it’s like you're being turned inside out, smeared, penetrated.”

Despite her facial piercing and techno-pagan accoutrements, Roberts has a sort of burned-out, aristocratic air that suggests Marianne Faithfull circa 1969. A half-smile flickering on her lips, as if she’s privy to some kosmik joke, Roberts speaks in a faded falter—as though some unutterably alien zone of posthuman consciousness hasn't quite relinquished its hold. Which may be a pretty accurate description of the state of play. If CCRU have something of a cultic air about them, OD go a lot further. Combining Mayan cosmology with ideas about Artificial Intelligence, they seem to believe that humanity will soon abandon the “meat” of incarnate existence and become pure spirit.

Throughout Cyberpositive there’s the recurrent exhortation “we must change for the machines;” while the book ends with the declaration—“human viewpoint redundant.” Not only do OD reckon Charles Manson had some good ideas, their East London HQ contains several cages of snakes—proof of their determination to get really serious about voodoo rites. The obsession was sparked by Gibson’s Count Zero, in which cyberspace has spontaneously generated entities equivalent to the loa (the spirit-gods of voudun cosmology). Throughout the interview, a shaven-headed OD member called Rich sits with baby boa constrictors wrapped around his body. His other contribution to the evening is to make some sandwiches—daintily quartered, but containing peanut butter mixed with sardines. "Too radical for me", I confess after one nibble. Rich's eyes

light up triumphantly: Mind-Game Over.

* * * * * *

“Cyberpositive” was originally the title of an essay by Sadie Plant and Nick Land. First aired at the 1992 drug culture symposium Pharmakon, “Cyberpositive” was a gauntlet thrown down at the Left-wing orthodoxies that still dominate British academia. The term “cyberpositive” was a twist on Norbert Wierner's ideas of “negative feedback” (homeostasis), and “positive feedback” (runaway tendencies, vicious circles). Where the conservative Wiener valorized “negative feedback,” Plant/Land re-positivized positive feedback—specifically the tendency of market forces to generate disorder and destabilize control structures.

“It was pretty obvious that a theoretically Left-leaning critique could be maintained quite happily but it wasn't ever going to get anywhere,” says Plant. “If there was going to be scope for any kind of....not ‘resistance,’ but any kind of discrepancy in the global consensus, then it was going to have to come from somewhere else.” As well as Deleuze & Guattari, another crucial influences were neo-Deleuzian theorist Manuel De Landa's idea of “capitalism as the system of antimarkets.” Plant and the CCRU enthuse about bottom-up, grass-roots, self-organizing activity: street markets, “the frontier zones of capitalism,” what De Landa calls “meshwork,” as opposed to corporate, top-down capitalism. It all sounds quite jovial, the way CCRU describe it now—a bustling bazaar culture of trade and “cutting deals.” But “Cyberpositive” actually reads like a nihilistic paean to the “cyberpathology of markets,” celebrating capitalism as “a viral contagion” and declaring “everything cyberpositive is an enemy of mankind.” In Nick Land’s essays like “Machinic Desire” and “Meltdown,” the tone of morbid glee is intensified to an apocalyptic pitch. There seems to be a perverse and literally anti-humanist identification with the “dark will” of capital and technology, as it “rips up political cultures, deletes traditions, dissolves subjectivities.”

This gloating delight in capital's deterritorializing virulence is the CCRU’s reaction to the stuffy complacency of Left-wing academic thought. “There's definitely a strong alliance in the academy between anti-market ideas and completely scleroticised, institutionalized thought,” says CCRU's Mark Fisher. “It's obvious that capitalism isn’t going to be brought down by its contradictions. Nothing ever died of contradictions!” Exulting in capitalism's permanent “crisis mode,” CCRU believe in the strategic application of pressure to accelerate the tendencies towards chaos.

Hungry for intellectual reasons-to-be-cheerful, CCRU simultaneously renounce postmodernism's wan fatalism (the idea that we're at the end of everything) and the guilt-wracked impotence of the Left. In the process, they've jettisoned the concept of “alienation” in both its Marxist and Freudian senses. They speak approvingly of “surplus value,” sublimation and commodity-fetishism as creative tendencies. Where “Cyberpositive” noted how how runaway capitalism had accessed “inconceivable alienations,” CCRU's collectively written essay “Swarmachines” goes further and climaxes with the boast: “alienated and loving it.” The idea, says Fisher, comes from a mix-and-blend of Lyotard and Blade Runner—“the proletariat as this synthetic class, and revolution that's on the side of the synthetic and artificial. The concept of ‘alienation’ depends on the notion that there's some authentic essence lost through the development of capitalism. But according to Barker, everything's already synthetic.” If reality really is a bio-mechanical, geocosmic continuum, there's no reason to resist capitalism’s escalating dynamic of anti-naturalism: addiction to hyper-stimulus, the creation of artificial desires.

The mania of CCRU's texts—with their mood-blend of euphoric anticipation and dystopian dread—is contagious. Much of the time they're trying to create a “theory-rush” that matches the buzz they get from contemporary sampladelic dance music; they describe, half-jokingly, what they do as “sub-bass materialism.” “The musical model is really key to us,” says Land. “It's absurd to say that music doesn't represent the real and therefore it’s an empty metaphor. Every theorist who hasn’t a real place for music ends up with one-dimensional melancholia.” Not only do the CCRU derive a lot of their energy from music (specifically drum & bass and UK garage, which one member of the unit actually makes and Djs under the name Kode 9) but popular culture is where their ideas seem most persuasive. Right from its late Eighties beginnings, rave culture’s motor has been anarcho-capitalist: from promoters throwing illegal parties in warehouses to drug dealing. Even after its co-optation by the record and clubbing industries, rave music's cutting edge comes from small labels, cottage-industry producers with home studios, specialist record stores, pirate radio. Sadie Plant attributes these bottom-up economic networks to the end of welfare and “dependency culture,” which forced people “to get real and find some ways of surviving” but also to invent “new forms of collectivity” (the micro-utopian communality of the rave).

As well as being galvanized by music, the CCRU are influenced by the theory-driven leading edge of music journalism. One of their associate members is Kodwo Eshun, contributor to iD and The Wire, and author of the book More Brilliant Than The Sun: Adventures In Sonic Fiction (Quartet), a study of Afro-futurist music from Sun Ra to 4 Hero. Eshun describes himself and the CCRU as “concept-engineers.” “Most theory contextualises, historicizes and cautions; the concept-engineer uses theory to speculate, excite and ignite,” Eshun proclaims. Like a DJ/producer, the concept-engineer is “a sample-finder,” free to suspend belief in the ultimate truth-value of a theory and simply use the bits that work (in the spirit of Deleuze & Guattari's offering up of A Thousand Plateaus as tool-kit rather than gospel).

“Concept-engineer” is a good tag for the outerzone of “independent researchers” to which CCRU is connected. Renegade autodidacts like Howard Slater, a Deleuze-freak whose techno-zine break/flow brilliantly analyzes rave culture in terms of “surges of intensity” and “impulsional exchanges.” And like Matthew Fuller, a media theorist/activist with a background in anarchist politics and links to the hacker underground. Fuller’s CV of cultural dissidence includes flypostering, a non-Internet bulletin board called Fast Breeder, the scabrous freesheet Underground, and a series of anarcho-seminars dedicated to the praxis of media terrorism. Fuller also put out the anthology Unnatural: Techno-Theory For A Contaminated Culture, which included Plant/Land's “Cyberpositive.”

Discussing his own cyber-theory writings, Fuller talks about dismantling traditional “modes of political address” and developing a sort of post-ideological realpolitik of resistance. A true concept-engineer, he believes in ransacking theory texts for task-specific ideas. “Publishers like Autonomedia and Semiotexte produce material that you don't have to be an academic to get into, so it circulates outside those milieux. When I give presentations at academic events, it's easy to see I'm in a more powerful position than the academics—I can steal all the advantages of their discipline, plus do something else with it that fucks it up totally.” Noting that Deleuze & Guattari are already being institutionalized into “the most dreary, saintly area of discourse,” Fuller says he’s dedicated to “cracking open those texts again, thinkers who originally opened stuff up to delirium and the irrational. I mix up different linguistic registers and narrative strategies so that the text writhes in the hands of the reader. In that respect, there's a lot more to be learned from fiction than theory.” Here Fuller chimes in with Sadie Plant, whose forthcoming Writing On Drugs will include a fictional component, and who hopes her future books will become “pure fiction.”

“The most enjoyable aspect of CCRU is that they are a gang—Ph.D. students with attitude!,” says Eshun. Loathing the “necrotic side of philosophy, the chewing-over of dead thinkers’ entrails,” and bored limp by the “delibidinising” atmosphere of seminars, CCRU used to attend academic events, claims Eshun, expressly “in order to disrupt, undermine and ridicule.... They'd get into pitched battles with Derrideans!"

Weary of such sports, Plant and CCRU have all enthusiastically embraced the idea of escaping “institutional lockdown” by going freelance. The CCRU hope to become a kind of independent think-tank, selling “commodities” on the intellectual free market—like their strikingly designed Abstract Culture (each “swarm” consists of five separate monographs bundled together) and, in the future, CD's, CD-ROM's and books.

It seems unlikely, however, that Plant and her erstwhile cronies will rejoin forces once they’re out in the freemarket wilderness. Some kind of ideological rift seems to have occurred. Plant says she couldn’t really go along with the trip into numerical mysticism, not least because she didn't like finding herself “in the role of the sensible, conservative one—not a role I'm used to!” CCRU, for their part, seem to have resented their guru’s premature departure from Warwick. “Nick Land's hermetic, he wants acolytes,” says Eshun. “Whereas Sadie’s this total communicator. Zeros + Ones is the return of the grand narrative with a vengeance. I can’t think of any other writer with the same ambition. Sadie wants the world and I think she'll get it.”

For CCRU work, post-CCRU activity, and allied ‘renegade autodidacts’ check out these sites:

Cybernetic Culture Research Unit -- http://www.ccru.net/

K-Gothic -- http://www.k-gothic.net/

Datacomb -- http://www.k-punk.net/k-punk.net

K-Punk -- http://k-punk.abstractdynamics.org/

Hyperdub -- http://www.hyperdub.com/

Kode 9 -- http://www.ccru.net/kode9.htm

Abstract Machines -- http://www.ccru.net/abstractmachines.htm

Orphan Drift -- http://www.orphandrift.com/

Matthew Fuller -- http://www.autonomedia.org/behindtheblip/index.html

(originally published in an abridged version by Springerin magazine, Vienna, 1999)

January 18, 2005

January 17, 2005

Colonials and Natives, and other stories

As I limber up for the next wave of long posts, some recommendations:

1. A finely honed volley of invective spat at the Royal Idiot by Philip Mind. (btw, doesn't the phrase 'Colonial and Natives' invite you to imagine an early 80s New Romantic band somewhere between Heaven 17 and Spandau Ballet? Or maybe the title of a missing track from Simple Minds' 'Empire and Dance'?) Course, ulimately, Harry is to be congratulated, on the grounds that anything which subtracts credibility from the monarchy must be enthusiastically welcomed.

2. 9 Ccru datastreams recovered from k-space oblivion at Sagittipotent.

3. Marcello excellent on AI. Most of the posters at alt.movies.kubrick were dismissive of Spielerg's claim to be 'completing' a Kubrick film, though, as MC suggests, the film does have real SK moments. The opening section, up until the point where David is expelled from the family, and the end section, in which David is reunited with a simulation-reincarnation of his 'mother', have always struck me as particularly powerful. Of the middle section, with Jude Law, the less said the better (only the Teddy Bear - much more lifelike than Jude - makes this uh bearable). The appearance of aliens onscreen was pure Spielberg (difficult to imagine Kubrick countenancing THAT).

4. The current Sea-themed edition of Cabinet magazine. Haven't come across this before, but some gratifyingly intelligent and erudite pieces, including 'The Sunset Coast' by Michael Bracewell, on the vulgar sublimity of the English seaside:

'A little further south from Heysham village, the coastal flatlands known as Middleton Sands still house the ruins of the old Pontins holiday camp — its ranks of derelict guest chalets grouped around a main building that was designed to resemble, and included original fittings from, an ocean liner. With the slogan "Cruising on Dry Land", this Pontins camp was typical of its era - the post-war, early Pop era of British holiday camps, the dawn of bottled colas, teenagers, and the Twist.

Visited now, the place has all the bewitching, elegiac charm of any Gothic ruin; the paint is peeling on the dry-docked liner with its scarlet-and-black funnels; the BMX cycle track is cracked with weeds. What remains is a ghost of the first Pop age and the golden years of the coastal holiday from the daily routine of work and family.'

5. The Aviator. Capitalism and Schizophrenia. War and cinema. Make sure you don't miss the opportunity to experience this sumptuous spectacle in the cinema. Scorsese at the peak of his powers. A long post here on this soon.

January 15, 2005

Human history begins to make sense, but it is no longer human

So many k-punk lines intersect in the passage I've reproduced below from Greil Marcus' Lipstick Traces.

For me, it's the best section of the book - the one which breaks out of the official counter-history (which in any case was even then, in 1989, not so secret) of the Dadaist, Lettrist and Situationist incursion into Pop via punk.

Instead, it produces-discovers a whole other micronarrative web connecting punk, the Freud of Moses and Monotheism and pulp SF. Anarchy in the UK as the realized death drive, as, that is to say, the revenge of the Real upon the reality principle....

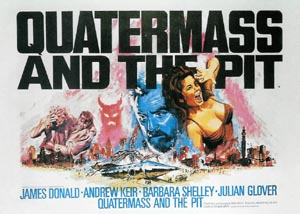

As ever a modernist stranded in postmodernity, all time-lines cut and reversed, I hadn't seen Quatermass and the Pit when I read Lipstick Traces in 1989. But Marcus' writing on it triggered flashes of artificial memory because, although I hadn't yet seen Quatermass and the Pit, I had, as you can hardly fail to know, seen Dr Who, which, especially in the Pertwee era, remixed Kneale's hypernaturalist premiss (demons as aliens, the aparently supernatural as the not yet understood scientific) many times.

I read Marcus' book as I laboured under a delusion in a temp factory job (yes, you can imagine how humiliatingly painful my pathetic attempt to function in that world of Real Men was), the downpressing weight of the Real World beginning to hit me in the first few months after graduating.

Of course, the passages on the poverty of everyday life, on the Situationist refusal of work, on punk's demanding of the impossible, the sense that we can't, we shouldn't live like this any more, struck a special chord then. There was I, doing cheap labour in someone else's misery before going onto 'something better' - although that 'something better' turned out to be, in the first instance, an attempt at an MA that ended in my first breakdown, followed by years of unemployment, dead end courses and micro-jobs - temporarily incarcerated with those for whom this was It, working life a forty year sentence of noise, dirt and tedium. (Though not, for them, in that factory; it closed a few years later). And, at that time, as the last of the Seventies Dream faded, I was required to hope for a job in Unilever or something. The memory of those graduate job brochures still fill me with a shivering existential horror: twenty-three year old kids talking about 'the opportunity for early responsibilidy', laughable corporate zombies being held up as some kind of ideal.

I never realised/ the lengths I'd have to go

Everything seemed over, not only for me, but for the whole culture.

Still living at home. Very few friends, none of them women. Those friends themselves locked into temp job misery, like me not having the will to pursue the career ambitions which are the goal of those who have lost any real ambition, or never had it in the first place.

The Marcus book could not but read elegiacally then. I guess that dreams always end. A series of postcards from lost futures, souvenir wreckage from worlds that could have been.

At the same time, it also operated as a storehouse of counter-cultural provisions, a Dreaming kit that, along with Lipstick Traces, Simon and David Stubbs in Melody Maker, the Wire, Vague, would sustain me through the desolate virtual nuclear winter at the fag end of the Cold War and the beginning of the End of History. It wasn't music criticism; like the Pop it described, this discourse was always about more than music: sound was only the vehicle for a raging against the mean inevitabilities and banalizing commonsense of the then smugly dominant reality principle.

And the shoots and spoors of a liveable future, then heartbreakingly far off (only another fifteen years Mark), were already there in those three or four pages by Marcus. A future in which my Seventies childhood would splice with my yet-to-be Junglized nineties dancing body, and with my yet-to-be cyberpunked theory-fiction mind.

Any way, here's Greil:

'I can compare the sensation this performance [the Sex Pistols' last, at San Francisco Winterland in 1978] produced only to Five Million Years to Earth, a film made in England in 1967 under the title Quatermass and the Pit.

The time and place is Swinging London, where the reconstruction of a subway station has revealed a large, oblong, metal object: a spaceship, as any moviegoer could tell the cops and bureaucrats who can’t. Near the object are the fossilized remains of apemen; within it are the perfectly preserved corpses of human-sized insects. The scientist Quatermass is called in.

Putting the pieces together, he determines that, five million years before, Martians—the insects—faced with the extinction of life on their own planet, sent a small band of scientists to earth. Their goal is to implant the Martian essence in an alien life form (the gimmick is a nice anticipation of the theory of the selfish gene): to find a home for the soul of the Martian race.

The Martians, Quatermass slowly learns, were by nature genocidal: the death of their planet is their own work. Indeed it is their masterpiece, and so to maintain themselves on earth they must destroy it. The Martian scientists select the most promising earth creatures—australopithecines, which emerged perhaps eight million years ago, and which most paleoanthropologists consider directly ancestral to our own genus—and, through genetic surgery, set a small group on the road to planetary dominance. Endowed with the Martian traits of cognition and bloodlust (the latter notion, in 1967, a nod to the fashionable human-origin theories of Robert Ardrey), the chosen australopithecines follow their coded path to Homo sapiens and inherit the earth. Once the new species has achieved the technology necessary to dominate nature, destiny will be manifested in its destruction.

But the graft is not perfect; the contradiction between earth and Martian genes is never fully absorbed. Though there is no consciousness of the intervention, there is a phylogenetic memory. Freud believed that modern people in some fashion remember, as actual events, the parricides he thought established human society, and unconsciously preserve that memory in otherwise inexplicably persistent myths and rituals; in Moses and Monotheism he argued that, hundreds of years after the fact, the Israelites carried a memory of their forebears’ murder of a first Moses, even though in oral and written traditions the event was completely suppressed. In Five Milliion Years to Earth the argument is that modern people remember step-parents who, with infinite patience, set out to kill their progeny—and the idea explains why, with their all-powerful science, the Martians did not simply wipe out life on earth as they found it. They meant to perpetuate themselves on earth by making its history—by coding its end in its beginning. A passion for prophecy, it seems, is also a Martian trait: they loved drama as much as death.

For Quatermass, all sorts of phenomena that as a scientist he has dismissed as relics of an irrational past take on a new meaning. Poring through books on ritual and myth, he begins to understand that along with its domination of nature, its march toward mastery and abundance, the new species has produced irreducible images of a primordial displacement. They are attempts to cast the alien out; to abstract the im planted traits from the body, to reify them into demonism. But there is a contradiction here too: it is only the alien intelligence that permits the species to engage in a process as complex as reification—a sort of fetishization of alienation, where human properties are transferred to things that human beings have themselves produced, things that then operate autonomously, finally turning human beings into things—and reification cuts a two-way street. Once expelled, once removed into a representation of the demonic, the alien presence casts a spell. Quatermass discovers that not only did the Martians put their name on the site of the subway station where their remains were found (frantic research reveals that its address, “Hobb's Lane,” once meant “Devil’s Haunt”), thus making it, in medieval times, a cursed place, they have, in the shape of the parthuman, part-horned-animal figure of “The Sorcerer,” inscribed their image on the wall of the Cro-Magnon sanctuary of Trois Frères, thus making it, in paleolithic times, a place of worship. ‘The Sorcerer” echoes across fifteen thousand years into an otherwise inexplicable Christian prayer: “The Lord is in this place, how dreadful is this place.” Human history begins to make sense, but it is no longer human.

The disturbance in the subway station calls up the dormant Martian presence. The spaceship begins to vibrate, and the energy released by the vibrations creates a vacuum. The vacuum sucks up sleeping genes, which create a repulsive, beckoning image: a glowing, horned devil, overshadowing London, the Martian Antichrist.

Across five million years, genetic drift is not uniform. By the twentieth century, some people are coded for destruction; some carry only a few broken alien messages. Some respond to the Martian image; some do not. For those who do, the ancient codes become language, and memories of the original Martian genocide course to the surface. For those who do not respond, language dissolves. Humanity is split into two species; there is anarchy in London. Men and women surge through the streets smashing all those they recognize as alien: all who carry less of the Martian essence than they do. The Martian image turns red. Hobbes’s state of nature was “the war of all against all”; this is it, and it is lurid beyond belief.

More human than Martian, Quatermass lives to see the demonic image vanquished and the Martian genes put back to sleep—but not before a comrade, more human than Quatermass, who can stand to gaze into the face of the image as Quatermass cannot, has been exploded in the attack. The image is pure phylogenetic energy; guiding a steel crane straight into it, Quatermass’ comrade negates the image with mass—a neat Einsteinian twist.

Quatermass’ assistant, more Martian than he, returns to his side as if awakened from a dream; minutes before, she was squeezing blood out of his neck. In a long, silent shot, the movie ends—and because there is no freeze frame, no auto-matic irony, the movie doesn’t seem to end at all. Quatermass and his assistant are seen in the wreckage of London; he leans on a ruined wall. Everything he has seen is in his eyes, and he is trying to forget what he has seen, but the shot—it goes on and on—doesn’t last long enough for his assistant’s eyes to focus.

Now it is plain that Five Million Years to Earth is a 1960s version of 1950s atomic-bomb-mutation films; an exculpatory allegory of Nazism and the Blitz; a quick and easy update of the gnostic heresy in which the world is split between equally empowered Good and Evil gods; a bid to make fast money off whatever dislocations might be circulating in modern society at any given time. It doesn’t play like that. It is progressively horrifying—especially at 2 A.M., when it is most readily seen on television; when, as Nietzsche wrote, “man permits himself to be lied to . . . when he dreams, and his moral sense never even tries to prevent this”; when there is no one with whom one might dominate the film. Quatermass’ victory is the victory of rational certainty over irrational doubt; the doubt in his face at the end is not doubt that he has won, but doubt that he wanted to. Perhaps it is no accident that, on occasion, the Late Show has cut the last twenty minutes: cut the anarchy, offering only the mystery, its formal solution, and then the film’s last shot, which no longer carries any meaning.'

Previous k-punk Quatermass postings:

Nonorganic Memory

Lay! Lay! Lay!

January 13, 2005

Who makes the nazis?

So much of the furore arising from the Prince Harry Nazi incident REEKS of hypocrisy... the current position of the Privet Hedge Brigade seems to be that it's bad form to DRESS as a Nazi, but it's OK to BE a Nazi (because, you know, the big Other might see) ... 'Tightening up on immigration', 'restricting the numbers of asylum seekers', all not only acceptable but practically mandatory in the current kapitalist parliamentarian regime.

Cue spluttering denials from behind the rhodendrons. 'Just because I want to send people back to their own countries doesn't mean I'm a Nazi'. Cut to Denholm Elliot in Brimstone and Treacle: No, I don't want camps and guns... Michael Kitchen: But what if they won't go? What then?

Reminds me of another phobic piece I saw in the Mail yesterday about the MILLIONS of illegal immigrants working here... Well, what would happen if we sent them back, Mr Dacre? Who'd clean the shit off the streets at five in the morning then?

You have to laugh at those who say that Harry should not now be able to join the Army. Surely he'll fit right in with 'our boys', those lovable queer-bashing psychopath squaddies who make the areas surrounding barracks such friendly and unthreatening places.. as if NO-ONE in the British Army has a collection of Nazi memorabilia...

Just to prove the point, look at 'former SAS man and old Etonian' Simon Mann, pictured on TV-AM this morning in chains in a Zimbabwe jail (I have to say, no day that begins with that image can be all bad)... Not surprisingly, the only person TV-AM could produce to defend poor, hard done-to Mark Thatcher was 'former MP' Jonathan Aitken. That's right, that's how he was billed - as 'former MP' not as 'former arms dealing liar and hypocrite'. Still, Mark 'just wants to be re-united with his family', so, like, he's a family man, and as we know, if you're a family man, well, you couldn't possibly be involved in a sordid mercenary plot aimed at stealing oil from Africa... And he's BRITISH, so a priori he shouldn't be subject to the barbaric judicial regimes of African countries, should he?

January 12, 2005

NO LONGER THE PLEASURES

I'm obv very pleased with the responses to the Joy Division post (lotsa links, including one from a Spanish site and a Dutch site, neither of which, as a language dimbo, I can understand - and sadly the online translators I tried were not up to the job).

Strikes me that one positive aspect of closing the comments boxes is that it takes things back to the early days of blogs, where people were much more likely to produce longer, thoughtful responses to posts on their own sites. This put blogs somewhere between a static website and a forum, avoiding the closure of the former and the free-for-all openness of the latter. The troll can only thrive on a forum, because there they can assume the role of Bradly Martin antagonist, the voice of faux objectivity, because they never have to lay their own cards on the table. That's impossible with a blog, which always comes from somewhere, has an agenda, a vision.

re: Amblongus' remarks: as it happens, I'm strongly nostalgic for the seventies, for its pre-Style glamour (I wonder if the rise of Style meant the end of Glam/our actually?). Something punctual seemed to happen round about 1982, and as Mark Sinker was saying to me in conversation, Curtis' death no doubt played an enormous role in that threshold shift into shoulder-padded, glossed-out blandness. The mid to late eighties still produces a shiver of Horror whenever I think back to it... You just have to flick through to the end of the NME's Goth thing... The Mission, Jesus, a strong candidate to be the worst group ever... That disgusting unkempt long hair, the cowboy boots and spurs, the palpable stench of patchouli oil rising up from every tedious crash chord...

As for Simon: an awful lot here, as always....

Will have to read Norman O Brown, Simon's obv right....

But I would want to reiterate the point that there is a version of the death drive (namely, Lacan's) that surpasses both vitalism and a conventional self-destructive sense of the Thanotropic. It's interesting that Nineties 'Deleuzianism' was in effect divided along those lines: in every sense the libidinal wing, occupied by theory renegades such as Nick Land and Iain Hamilton Grant versus the dead hand of sensible, academic careerist vitalism, whose too-numerous-to-name advocates (autopoioeidipalists - as Iain gloriously labelled them) united in the prayer, 'emerge, emerge' (Iain again).

I remember, in what must have been 1983, asking a fellow JD cultist (being into Joy Division for me was pretty straightforwardly a religion, a cult in the strong sense, a badge of non-membership in the teenage world of empty hedonism): 'Why is it that negative things are so much more attractive than positive things?'

Seems to me that its crucial to go all the way through the libido of the negative - to utterly resist the commonsense privileging of the vital whilst NOT getting Curtis syndrome. The r and r young death thing was so self-conscious --- from what Deborah Curtis says, Ian C was fixated on this since his own teenage years:

‘His fanatacism for David Bowie, and in particular his version of Jacques Brel’s song ‘My Death’, was taken at the time to be a fashionable fascination.’ (5)

‘When Mott the Hoople’s ‘All You Young Dudes’ hit the charts, Ian began to use the lyrics as his creed. He would choose certain songs and lyrics such as ‘Speed child, don’t wanna stay alive when you’re twenty-five’, or David Bowie’s ‘Rock and Roll Suicide’ , and be carried away with the romantic magic of an early death. He idolized people like Jim Morrison who died at their peak. This was the first indication anyone had that he was becoming fascinated with the idea of not living beyond his early twenties, and the start of the glitter and glamour period in his life.’ (7)

Of course all of this is itself a self-conscious echo of the Romantic cult of the dead young poet, which began with Chatterton (the whole myth of which was wonderfully exploded by Ackroyd in his hyperfictional novel).... But the poet who longs for an early exit is not straightforwardly 'in love with easeful death': what he (and the gendered term here is no accident) feared was the intensive death of a life 'pointlessly' prolonged into what Kodwo called 'the coffin of adulthood'. To die prematurely is to be forever young, to attain the 'cold pastoral' of Keats' grecian urn...

But the Lacanian sense of the death drive is neither to do with that, NOR to do with Buddhist cessatation: the death drive is that which is genuinely beyond the pleasure principle. The pleasure principle seeks satiation, the release of tension - which is why the Nirvana principle, the drive towards total quiescence, still belongs to it. Only a drive which is hostile to all closure, all quiescence, moves beyond the organs and the pleasures of the organs. This is what D/G mean by the plateau --- and the plateau's relationship to anti-climactic dance music means there is a way of conceiving of sonic stim which has little to do with the agitational impulses of the organism. Apparently paradoxically, dancing involves a stillness, or rather, an effective stilling of the organism's endless quest to be always elsewhere (this especially a feature of organisms suffering from TMT, Too Much Testosterone), an enjoyment in and through tension that resists any orgasmic culmination-consummation.

So: for me, it's always dance, not meditation. The body without organs, not bodilessness. .. . (A whole other post on the route from 'She's Lost Control' through to House is necessary, I think...)

As for the icy calm of Closer: yes... One thing that I heard many times from people on Psych wards that had been very serious and very methodical about ending their lives was the feeling of total calm that came over them when they had really decided to go ahead and do it. That is what is disturbing about the very last Joy Division music, the sense that you are listening to someone who is already dead...

The early 70s thing and speed... yes, obviously what Simon said is true. And yet, I think one thing that has achieved near-consensual support on our part of the blogosphere is the destruction of the myth that the early 70s was a barren period for music. Reading the NME's Glam thing a few months back, I felt exactly the opposite: that there has never been a more sustained, brilliant period for pop than in those Glam years. Lumpen punk was a tedious r and r distraction, before the Glam Discontinuum resumed in postpunk.

As for the relationship to speed, the drug... well, yes, no doubt downers did gain more prominence in the early 70s... but in the more abstract, McLuhanite sense, pop culture was still 'speeding' in the early 70s, still relentlessly hungry for new forms of expression, new connections.... Pop was still modernist in other words... Need to think more about all this, however...

Also got a few things to say about why speed locks into cyberpunk.. but that'll have to wait... too tired to carry on typing now...

January 11, 2005

Calling all reactive agents

FASTER AND FASTER downhill, tearing his clothing on rocks and thorny vines, and by dusk he was back at the settlement. He knew at once that he Was too late, that something was horribly wrong. No one would meet his eye. Then he saw Bradley Martin, standing over a dying lemur.

Mission could see that the lemur had been shot through the body. He felt a concentration of rage, like a hot red wave, but there was no reciprocal anger in Martin.

‘Why?’ Mission choked out.

‘Stole my mango,’ Martin muttered insolently.

Mission’s hand flew to the butt of his pistol.

Martin laughed. ‘You would violate your own Article, Captain?’

‘No. But I will remind you of Article Twenty-Three: If two parties have a disagreement that cannot be settled, then the rule of the duel is applicable.’

‘Aye, but I have the right to refuse your challenge, and I do.’

Martin was an indifferent swordsman and a poor pistol shot.

‘Then you must leave Libertatia, this very night, before the sun shall set. You have no more than an hour.’

Without a word, Martin turned away and walked off in the direction of his dwelling. Mission covered the dead lemur with a tarpaulin, intending to take the body into the jungle and bury it the following morning.

IN HIS QUARTERS Mission was suddenly overcome by a paralyzing fatigue. He knew that he should follow Martin and settle the matter, but — as Martin had said—his own Articles . . . He lay down and fell immediately into a deep sleep. He dreamed that there were dead lemurs scattered through the settlement, woke up at dawn with tears streaming down his face. 1

MISSION DRESSED AND went out to get the dead lemur, but the lemur and the tarpaulin were both gone. With blinding clarity he understood whyMarttin had shot the lemur, and what he intended to do: he would go to the natives and say that the settlers were killing the lemurs and that, when he objected, they turned on him and he had barely escaped with life. Lemurs were sacred to the natives in the area, and there was the danger of bloody reprisal.

Mission blamed himself bitterly for allowing Martin to escape. No use to go looking for him now. The damage was already done, and the natives would never believe Mission’s denials.’

BIG BEN STRIKES the hour. In a muted, ghostly room, the custodians of the future convene. Keeper of the Board Books: Mektoub, it is written. And they don’t want it changed.

‘If three hundred men—then three thousand, thirty thousand. It could spread everywhere. It must be stopped now.’

‘Our man Martin is on target. Quite reliable.’

A woman leans slightly forward. An arrest ing face of timeless beauty and evil, an evil that stops the breath like a deadly gas. The chairman covers his face with a handkerchief.

She speaks in a cold, brittle voice, each word a chip of obsidian: ‘There is a more significant danger. I refer to Captain Mission’s unwholesome concern with lemurs.’

The word slithers out of her mouth writhing with hatred.

THERE ARE NO further repercussions from the incident with Martin. But Mission does not slacken his precautions. He can feel Martin out there waiting his time with the cold reptilian patience of the perfect agent.

He had underestimated Martin from the beginning by not seeing him. Martin had the capacity to create a lack of interest in himself. 2 Even his position was ambiguous, something between a petty officer and a member of the crew. But since there were no petty officers, he occupied an empty space. And he made no attempt to fill it. When told to do something he did it quickly and efficiently. Yet he made no attempt to make himself useful.

Since Mission found contact with Martin vaguely disagreeable - he asked him to do less and less. Mission was displeased that Martin chose to join the settlers, but he did his share of the work and bothered no one. When he was not working he would simply sit, his face as empty as a plate. He was a large, sloppy man with a round pasty face and yellow hair. His eyes were dull and cold like lead.

Mission saw Martin for the first time as they confronted each other over the dying lemur. And what he saw inspired in him a deadly, implacable hatred.

He sees Martin as the paid servant of everything he detests. No quarter - no compromise is possible. This is war to extermination.

1. Consider the inexorable logic of the Big Lie. If a man has a consuming love for cats and dedicates himself to the protection of cats, you have only to accuse him of killing and mistreating cats. lie will have the unmistakable ring of truth, whereas his outraged denials will reek of falsehood and evasion. [...]

2. If you wish to conceal anything - you have only to create a lack of interest in the place where it is hidden.

Burroughs, Ghost of Chance

January 09, 2005

Nihil Rebound: Joy Division

"If you shoot yourself, you'll become God, isn't that right?"

"Yes, I'll become God." – Dostoyevsky, The Devils

‘… [O]ut of the corner of my eye I saw him. He was kneeling in the kitchen. I was relieved – glad he was still there ‘Now what are you up to?’ I took a step towards him, about to speak. His head was bowed, his hands resting on the washing machine. I stared at him, he was so still. Then the rope – I hadn’t noticed the rope. The rope from the clothes rack was around his neck. I ran through to the sitting room and picked up the telephone. No, supposing I was wrong – another false alarm. I ran back to the kitchen and looked at his face – a long string of saliva hung from his mouth. Yes, he really had done it…’ - Deborah Curtis, Touching From a Distance: Ian Curtis and Joy Division, 133

So there it is, sublimation and desublimation. Suicide as Theological Art work (‘I’ll become God’), and suicide as a pathetic mess (‘a long string of saliva’) for someone else to clear up.

This post has been inevitable for over two decades.

But it has been given particular impetus by three recent encounters.

1. The NME’s Goth special, which, amongst other things, collects together the Joy Division reviews. Strange in many ways to see them canonized as Goth princes. There was no question of course that theirs was a fiercely expressionist sound – a sound in fact that was much more genuinely Gothic than that of the Caligari-faced panto turns who have appropriated the name or who have delighted in having had it foisted upon them. Yes, Joy Division, with the ‘witchy emptiness’ of the Pennines weighing heavy upon them, had produced what Jon Savage called ‘the definitive Northern Gothic statement’. They had transmuted what ‘the Manchester damp and the shadows and omen called into dread being by the hills and moors that lurked at the edge of their vision’ (Morley) into the darkest machine Pop, a terminus of the Gothic ‘Northern line’ in a Pop rigor mortified into anxious mechanism. Yet the austerity of Joy Division’s image – their staged refusal of Image – set them at odds with the post-Bowie mummery of the Banshees, the Cure, Bauhaus and their diminishing returns photocopy-of-photocopies offspring. They were Gothic, but not Goths, surely.

2. A conversation with Kodwo at the Noise conference, lines coming out of his pieces on Closer and Movement. Kodwo recognized that ‘moving on’ from Joy Division involved disavowal, in the strongest sense. ‘I can't help but feel this music as a missing part of my body, a part I sacrificed at the stake of Black British life.’ Joy Division were a cult, but a hermeticists’ cult, a cult of those who didn’t belong and who didn’t want to belong, a bedroom communion between those who would never meet.

New Order, more than anyone else, were in flight from the mausoleum edifice of Joy Division, and had finally achieved severance by 1990. The England world cup song, cavorting around with beery, leery Keith Allen, a man who for me more than any other personifies the quotidian masculinism of overground Brit bloke culture in the late eighties and nineties, was a consummate act of desublimation. This, in the end, was the ‘price of escaping [the] anxiety of influence (the influence of themselves).’ On Movement they were still in post-traumatic stress, frozen into a barely communicative trance (‘The noise that surrounds me/ so loud in my head…’) ‘They were moving towards an electronic post-punk fusion here for which there were simply no rules as yet. It's almost as if what they started here - on 'Doubts Even Here' and 'The Him' especially, with its churning, blizzard-against-the-windshield hail of sound - frightened them, and they pulled back towards something more manageable.’

3. A conversation with Mark Sinker at the k-punk/ Infinite Thought kristmas party. It was clear that Mark and I had were at opposite sides of an irrevocable break, or time-cut, a cultural chronos-chasm.

I didn’t hear Joy Division until 1982, so, for me, Curtis was always-already dead (the hanged man harbinger of the endlessly circulating no-time of non-live media). Mark however experienced the Curtis death ‘in becoming’ – as a closing down of possibilities that were then very much live, as a contingency not a Necessity, as mess, not Myth.

Even though I could hardly have been aware of it back then, in 1982 Pop was living off stored-up energy, playing out formulae and designs that had already been produced but were now discontinued. The source had expired, collapsed into a dead star named Ian Curtis. Curtis’ death warped everything in the Pop landscape, removing the urgency from the Modernist impulse to endlessly re-invent, providing an alibi for those who wanted to retrench, return.

Everything had already happened, though we didn’t know it yet. In fact, though, the retreat from punk modernism into postmodernism, from avant-Pop to New Pop, had been almost immediate, Mark claimed. ‘People thought they’d rather not have to hang themselves as part of their job, if possible.’

Asylyums with doors open wide

When I first heard Joy Division, aged 14, it was like that moment in In the Mouth of Madness when Sutter Cane forces John Trent to read the novel, the hyperfiction, in which he is already immersed: my whole future life, Good and Bad, intensely compacted into those deliReal sound images - Ballard, Burroughs, dub, disco, Gothic, antidepressants, psych wards, overdoses, slashed wrists. Way too much stim to even begin to assimilate. Even they didn’t understand what they were doing. How on earth could I, then?

It was clear, in the best interviews the band ever gave - to Jon Savage, a decade and a half after Curtis’s death - that they had no idea what they were doing, and no desire to learn. Of Curtis’ disturbing-compelling hyper-charged stage trance spasms and of his disturbing-compelling catatonic downer words, they said nothing and asked nothing, for fear of destroying the magic. They were unwitting necromancers who had stumbled on a formula for channelling voices, apprentices without a sorcerer.