Remains to be Seen traces the ashes of Joe Hill from their distribution in Chicago to wartime New Zealand. Drawing on previously unseen archival material, it examines the persecution of anarchists, socialists and Wobblies in New Zealand during the First World War. It also explores how intense censorship measures—put in place by the National Coalition Government of William Massey and zealously enforced by New Zealand’s Solicitor-General, Sir John Salmond—effectively silenced and suppressed the IWW in New Zealand.

The richly illustrated book, and downloadable PDF, is now available from Rebel Press, or at the foot of this article.

On the eve of his execution, Joe Hill—radical songwriter, union organiser and member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)—penned one final telegram from his Utah prison cell: “Could you arrange to have my body hauled to the state line to be buried? I don’t want to be found dead in Utah.”1 His fellow ‘Wobblies’, remaining faithful to his Last Will, did one better. After two massive funerals (the second in Chicago involving over 30,000 people), Hill’s body was cremated, his ashes placed into tiny packets and sent to IWW ‘Locals’, sympathetic organizations and individuals around the world. Among the nations said to receive Hill’s ashes, New Zealand is listed: “Hill’s ashes were placed in envelopes and distributed to IWW locals in every state but Utah. Envelopes were also sent to South America, Europe, Asia, South Africa, New Zealand, and Australia.”2

Yet nothing is known about what happened to the ashes of Joe Hill in New Zealand. Even the late Bert Roth, meticulous researcher and pioneer of New Zealand radical labour history, found scant answers to his own search in the 1960s.3 Were Hill’s ashes really sent to New Zealand? Or was New Zealand simply listed to give such a symbolic act more scope? If they did make it, what happened to them?

The ashes of Joe Hill themselves are shrouded in myth. Prevailing accounts of what happened to Hill’s body upon cremation are riddled with factual errors and embellishment. For example, the date of the distribution of Hill’s ashes— believed for so long to be May Day 1916—is wrong. Actual examples of ceremonies involving Hill’s ashes are also few and far between, and due to massive state censorship and suppression of the IWW any documentation of other ceremonies has been lost or destroyed. Such factors make it difficult to pinpoint the exact fate of Joe Hill’s ashes in New Zealand.

Despite the fact that no concrete evidence has been found, there is every reason to believe that the ashes of Joe Hill were indeed sent to New Zealand. IWW cultural endeavours were common in the country, there were members of the IWW and organised IWW Locals in many of its towns and cities, and despite state repression, there were still echoes of the IWW reverberating inside the New Zealand labour movement at the time Hill’s ashes were distributed.

However by 1917 the IWW in New Zealand had been whittled down to a scattering of individuals, violently smashed by a united front of employers and government during the Great Strike of 1913, and targeted throughout the First World War by regulations designed to stamp out militant labour and the Wobblies once and for all. Alongside anarchists and other radical socialists, New Zealand Wobblies felt the full force of the state.

While the repression faced by the IWW in New Zealand pales when compared with the brutality inflicted on the American IWW, New Zealand Wobblies nonetheless suffered severe persecution by the National Coalition Government. Many were arrested and imprisoned for twelve months with hard labour, while their publications were singled out and scrutinised. Although there is evidence to suggest that the industrial tactics of the Wobblies such as the ‘go-slow’ actually increased after the Great Strike,4 to preach revolutionary syndicalism at that time—on a street corner or in writing—was a sure way of ending up in jail.

New Zealand during (and after) the War was far from an ideal environment for Wobblies and their anti-militarist, anti-capitalist material. As well as the extreme jingoism caused by the nation’s involvement in the First World War, IWW ephemera faced far-reaching censorship measures put in place by the New Zealand government and, in particular, by Sir John Salmond—Solicitor-General and self-imposed guardian of the New Zealand state. Both internal and international correspondence was stopped, censored, or destroyed by a team of censors working under the control of the New Zealand Military, which in turn, was guided by Sir John Salmond.

Through the monitoring and censorship of IWW material and the targeting of Wobblies themselves, ‘Salmond’s State’ effectively “extinguished the flames that the (IWW) movement fanned.”5 Salmond’s accusing eye and his keen interest in suppressing material of the ‘mischievous’ kind played a pivotal role in silencing the New Zealand IWW during the First World War and, in turn, is likely to have determined the fate of Joe Hill’s ashes.

Joe Hill: murdered minstrel of toil

There are a number of books, articles and other cultural productions about the life of Joe Hill, though his farcical trial and subsequent execution on 19 November 1915 has some-times overshadowed his achievements as an organiser and writer of radical songs.6 With this comes the notion put forward by Hill’s detractors that his legend was ‘blown up’ after his death: “a far less authentic martyr than Little, Everest, Ford, Suhr [other Wobbly martyrs] or a half-dozen others, Joe Hill was easier to blow up to martyrdom because he had the poet’s knack of self-dramatization.”7

However such a view obscures the tremendous influence of Joe Hill’s songs and the importance of cultural forms in the struggle for social change—of creating, as Hill’s biographer Franklin Rosemont put it, a “working class counter-culture.” Those in power were certainly threatened by the existence of such forms and, as we shall see, used a number of means to stamp them out.

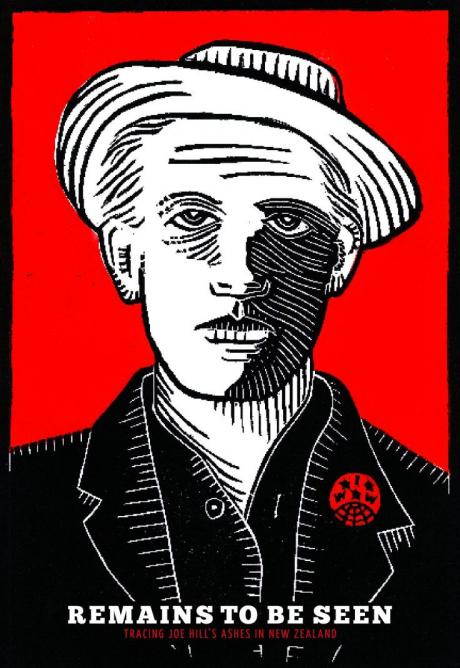

In an iconic linocut poster of Joe Hill, Wobbly artist Carlos Cortez rightly celebrates the many facets of Joe Hill: “union organiser, labor agitator, cartoonist, poet, musician, composer, itinerant worker, arbetarsangaren”—whose songs, as Cortez points out, “are still being sung.” Musicologist and author Wayne Hampton cites Joe Hill as “the most important protest songwriter in the history of the American labor movement,” placing Hill alongside John Lennon, Woodie Guthrie and Bob Dylan as the four most powerful “Guerrilla Minstrels” of the twentieth century.8 Indeed, the influence of Joe Hill and his songs have reached far and wide:

the rich ore of Joe Hill’s life and legend has been mined by many writers and poets. Joe Hill is found in books of fiction by Archie Binns; Elias Tombenkin; John Dos Passos; Margaret Graham; Alexander Saxton; and a number of others. He is found in plays by Upton Sinclair; Louis Lembert; and Arturo Giovannitti. He is found in poems by Kenneth Patchen; Kenneth Rexroth; Carl Sandburg; Alfred Hayes; and Carlos Cortez… Joe Hill appears in every kind of book from cultural studies to regional history books to books on revolutions and natural history…9

Not bad for a Swedish migrant worker, who, after emigrating to America in 1902 and working a string of jobs (including work on the San Pedro, California docks), found a home agitating and organising on behalf of the Industrial Workers of the World.

Many a Wobbly (and historians) believe that it was Hill’s organising that prompted his arrest and execution for the murder of shopkeeper John G Morrison, and his son, on the night of 10 January 1914. The murder—which appeared to Police as a crime of revenge—was attributed to Hill despite circumstantial evidence and international outcry. On 19 November 1915, Joe Hill faced the firing squad to the dismay of Wobblies, liberals, and even figures hostile to labour (such as US President Woodrow Wilson).

Admittedly, Hill’s trial and execution, so publicly played out in America and around the world, makes for rich folklore. But such an event alone does not explain the longevity of Hill’s influence. As Gibbs Smith points out in his seminal biography of Joe Hill, the simple reason was the legacy of his songs: “without them Hill would probably have been just another forgotten migrant worker.”10

Joe Hill’s songs spoke to, and engaged with, his fellow-workers, “turning into lyrical expression their everyday experience of disillusionment, hardship, bitterness, and injustice.”11 From rhymes about strikes to parodies of religious hymns, the songs of Joe Hill were both educational and organisational tools—conveying radical ideas more success-fully than a pamphlet or book ever could. And they were popular too: “Joe Hill’s songs swept across the country; they were sung in jails, jungles, picket lines, demonstrations. IWW sailors carried them to other countries. Wobblies knew their words as well as they knew the first sentence to the IWW preamble.”12

The songs of Joe Hill were certainly well received in Australasia. In New Zealand, The Little Red Song Book, one of the IWW’s most popular pamphlets consisting of revolutionary parodies and prose, helped spread Joe Hill’s songs amongst the labour movement of the day. Even the New Zealand weekly, Truth, quoted Joe Hill’s lyrics on occasion:

All of which reminds “Critic” of the words of Joe Hill’s song:

You will eat bye-and-bye,

In the glorious land above the sky:

Work and pray, live on hay,

You’ll get pie in the sky when you die.13

On Australian street corners Wobblies battled the Salvation Army in song, using Hill’s work and the Little Red Song Book to tremendous effect. “We used to have some really good singing at our meetings,” recalls Tom Barker, influential member of both the New Zealand and Australian IWW, and editor of its paper Direct Action:

as a matter of fact, we usually picked up the Salvation Army crowd when they had finished and marched away… we were waiting behind the girls with the poke bonnets and, once they’d given the big drum a bang and set off, we’d take over, put up our platform and carry on with the philosophy of the working class as we saw it.14

At union meetings up and down Australia one could hear “many a sweet voice singing cheerfully the songs of the IWW.”15 A particular favourite of Australian workers was ‘The Preacher and the Slave’ (also known as ‘Pie in the Sky’) quoted above.

Such popularity suggests that Joe Hill was no stranger to Australian and New Zealand shores, at least in song. Culturally, the IWW was well established ‘down under’ at the time of Hill’s final act—the dividing and distribution of his cremated remains. The story that his ashes came to New Zealand after his execution is not as far-fetched as it seems on first reading. Whether they made it past the New Zealand authorities however, is a story in itself.

The myth of May Day 1916

While his songs about capitalism, the plight of the working class and the possibility of a better world live on, so have myths around the distribution of Joe Hill’s ashes—nurtured by contributions from friend and foe alike. These contributions, factual or otherwise, have helped shape the prevailing account of Joe Hill’s ashes.

Joseph Hillstrom was cremated at Graceland Cemetery on 26 November 1915, his funeral the previous day having filled all 5,000 seats of Chicago’s West Side Auditorium.16 According to almost every narrative on Joe Hill, his ashes were then scattered around the world on 1 May 1916, (May Day). Barrie Stavis, author of the biographical play The Man Who Never Died, wrote:

Joe Hill’s ashes were placed in many small envelopes. These were sent to IWW members and sympathizers in all forty-eight states of the United States except one, the State of Utah… and to every country in South America, to Europe, to Asia, to Australia, to New Zealand and to South Africa. With fitting ceremonies and the singing of his songs, on May 1, 1916, the ashes of Joe Hill were scattered over the earth in these many countries.17

This, or similar variations on the May Day 1916 theme, has become Wobbly folklore. However it was not until the first anniversary of Hill’s death six months later (19 November 1916) that his ashes were actually distributed. Tiny packets containing the ashes of Joe Hill were given to delegates in Chicago for the IWW’s Tenth Convention, due to take place the following day. The rest of the packets were then posted on 3 January 1917.

The New York Times of 20 November 1916, reported: “one hundred and fifty of the envelopes were given to the IWW delegates at the Joe Hill meeting… the remaining 450 will be sent to IWW locals throughout the land.”18 In slightly more poetic terms the Industrial Worker, paper of the American IWW, noted:

in the presence of a great gathering of the workers and with impressive ceremony, Wm D. Haywood, General-Secretary Treasurer of the Industrial Workers of the World presented packets of the ashes of our murdered Fellow Worker to the delegates to the tenth convention of the organization and to fraternal delegates from the organised workers of other countries.19

Each packet bore a photograph of Joe Hill and the headline: “Joe Hill. Murdered by the Capitalist Class. November 19, 1915”; on the reverse was Hill’s Last Will and the words, “We Never Forget.” Packets that were sent by mail included a letter detailing Hill’s last wishes and a card instructing each “Fellow Worker” to “kindly address a letter to Wm D. Haywood, Room 307, 164 W. Washington St., Chicago, Ill., telling the circumstances and where the ashes were distributed.”20

Unfortunately none of these return letters have survived. Nationwide raids on IWW headquarters by the United States Government on 5 September 1917, and the subsequent destruction of IWW files has meant the loss of valuable information regarding the final distribution of Hill’s ashes. “From the Chicago HQ alone the authorities confiscated over five tons of material,”21 material that could have clarified what kind of ceremonies took place, when they took place, and where.

Of the few that have been documented it appears none took place on May Day 1916, as previously believed. One reference to a May Day ceremony appears in the 1932 novel Nineteen Nineteen by John Dos Passos, though it mentions no year. In 1948 Wallace Stegner wrote in the New Republic that “little envelopes of Joe Hill’s ashes were scattered next May Day [1916] over every state in the union and every country in the world.”22 Two years later in his fictional account of Joe Hill’s life, Stegner opens with a chapter titled “May Day 1916”, which describes a ceremony at Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Seattle. The notion that such ceremonies took place simultaneously around the world in 1916 is also reaffirmed: “…on that May Day, in every country in the world and every state in the Union except one, tiny envelopes of Joe Hill’s dust were being scattered.”23

There is evidence of such a ceremony in Seattle and it did take place on May Day, but in 1917, not 1916. Several thousand Wobblies and their supporters marched to Mount Pleasant Cemetery and scattered the ashes of Joe Hill over the grave of fellow IWW martyrs John Looney, Felix Baran and Hugo Gerlot, victims of the Everett Massacre.24

Of course it is not impossible that some kind of informal ceremony could have taken place before the ashes were officially given out, but it seems odd that the IWW would promote an early ceremony and therefore detract from the highly symbolic gathering organised for the anniversary of his execution.

Significantly, Stegner’s embellished account appears to be the source of the incorrect date used by subsequent historians. His novel was the first of a string of books released around the 1950s that revisited the life and death of Joe Hill and helped nourish his legend, although Stegner’s book and his earlier article was far from sympathetic to Hill—believing him to be “as violent an IWW as ever lived” and guilty of the murder for which he was executed.25

Instead of fertilising the world on May Day 1916, it seems that the ashes of Joe Hill were still firmly sealed in the IWW safe, waiting to be released on the first anniversary of his death.

To supporters in every inhabited continent on the globe

If the mistaken date on which Hill’s ashes were scattered has been accepted for so long, it is plausible that the list of countries where they were sent could also be wrong. Unlike the mistaken date however, the list of places said to have received Hill’s ashes originates with a more authoritative source.

Ralph Chaplin’s 1948 autobiography Wobbly was the first to list the countries where Hill’s ashes were sent, including New Zealand.26 Before Chaplin’s book, references to where they were actually sent were vague, preferring ‘in every state of the union’ or simply ‘around the world.’ Chaplin—a fellow IWW artist-poet and member of the five-person committee in charge of Hill’s cremation—kept Hill’s memory alive with frequent articles on Joe Hill in widely distributed labour papers such as New Masses and International Socialist Review.27 His eyewitness account of the funeral and cremation is the primary source for biographers of Joe Hill.

It must be considered that at the time of writing his book Chaplin simply listed current or past locals from around the world in order to give the act a sense of grandeur, regardless of whether the ashes were actually sent there or not. Chaplin had been the editor of the American IWW’s Eastern newspaper Solidarity, had written numerous poems about Hill, and was an accomplished Wobbly propagandist. However his listing of specific countries is likely to be credible, due to his intimate involvement with Hill’s funerals and cremation, and his central role within the organization itself. Of all the Wobblies active at that time, Chaplin’s cultural sensibility would have made him at the least interested in, if not the instigator of, such an encompassing event.

Ironically, by 1948 Chaplin had become a Christian, and while not going as far as repudiating the IWW he certainly was not writing his autobiography in order to preach the gospel of the ‘One Big Union.’ This, and the fact that a number of countries did receive Hill’s ashes as Chaplin described, lends credibility to Chaplin’s list.

One country that is known to have received Hill’s ashes by mail in 1917 was New Zealand’s nearest neighbour, Australia. Much to his surprise, Tom Barker received an unexpected package one Saturday morning:

to my astonishment, I got a parcel from the IWW organization at Salt Lake City containing a portion of the ashes of Joe Hill. We decided that we would have a ceremonial depositing of the ashes on the following Sunday in the garden near the Domain [the largest public space in central Sydney], so we could say that we had Joe planted firmly in Australia. The plan would have worked except for one thing—about two hours afterwards the police raided us.28

Barker and his fellow Wobblies were removed while the police went to work, ransacking the offices and confiscating material. When Barker returned, Hill’s ashes had gone. Asking the Chief at the Central Police Station about them, he was told: “you’re too late, I threw them in the back of the fire.”29

If Wobblies in Australia received Hill’s ashes by mail as Chaplin had indicated, there is reason to believe New Zealand Wobblies could have been sent them as well. According to the proceedings of the Tenth Convention of the IWW, no New Zealander was present at that convention, which suggests any ashes bound for New Zealand would have been posted there rather than distributed by hand in Chicago.30 At that time Australia and New Zealand shared the same postal shipping lines, with Sydney mail arriving from the Northern Hemisphere by way of Auckland.31 It would have been no more difficult to send Hill’s ashes to an address in New Zealand than to send them to Australia. In fact, New Zealand had been receiving a steady stream of IWW material by mail ever since the IWW’s 1905 inaugural convention in Chicago.

Sowing the seeds of rebellion

The modernisation of international postal lines, the inter-national character of IWW ideas, and the transient nature of those who adhered to them meant New Zealand Wobblies were far from isolated. The popularity of the IWW’s songs and the influx of IWW literature in New Zealand suggest that Chaplin’s claim of New Zealand receiving Hill’s ashes is highly credible.

The IWW’s origins and growth in New Zealand was typical of working class fermentation around the globe in the years leading up to the First World War. In response to the failure of unionism divided by trade and in order to combat the ever-increasing scope of capital, the ideas and tactics of revolutionary syndicalism gained adherents in many corners of the world. Radical socialists and anarchists found fertile ground for their ideas amongst the working class, and New Zealand was no different.

In 1908 the first IWW Local was formed in the capital, Wellington, with the intention of transcending trade unionism that “plays into the hands of capital to the enslavement and misleading of labour.”32 Before the outbreak of the First World War other Locals were formed in the cities of Auckland and Christchurch, while informal groups sprung up in industrial towns such as Huntly, Waihi and Denniston. In 1912 the Auckland Local “received its charter from the IWW headquarters in Chicago, becoming Local 175.”33

However, New Zealand’s connection to the American IWW goes back even further than 1908. According to Roth a number of Kiwi miners were present at the 1905 inaugural convention of the IWW in Chicago, including “Jones, later secretary of the Paparoa Miners’ Union.”34 William Trautmann, co-founder of the IWW and key speaker at the Chicago convention, was born in New Zealand and often spoke of his New Zealand roots.35 The New Zealand Socialist Party, through their paper Commonweal, had “voiced the creed of the Industrial Workers of the World” since 1906,36 while roaming revolutionaries such as Canadian H M Fitzgerald—much like IWW literature—bridged the gap between northern and southern hemispheres. ‘Fellow-worker’, the term Wobblies used to address each other in America, quickly replaced ‘comrade’ in New Zealand.37

Pamphlets and newspapers of the IWW had a wide circulation in New Zealand. The Wellington branch of the Socialist Party “found that it failed to anticipate the demand for American pamphlets.”38 According to the Secretary of the Waihi branch, imported IWW anti-militarist pamphlets were “finding a ready sale” in Waihi.39 Chunks of IWWism and Industrial Unionism, two New Zealand IWW pamphlets, sold in quantities of 3,000 and 1,000 copies each, while the Industrial Unionist, newspaper of the New Zealand IWW, reached a circulation of 4,000 (when the population of the entire country was little more than a million).40

As Mark Derby has pointed out, the distribution of cheap printed propaganda was vital to the spread of IWW ideas and tactics. “New Zealand Wobblies relied on the impact of IWW literature such as the Little Red Songbook,” moving from town to town “sowing the seed of rebellion.”41 The existence and spread of such material in New Zealand would suggest that Hill’s ashes, like past Wobbly propaganda, could have easily been sent to the Dominion.

The popularity of IWW, anarchist and revolutionary syndicalist literature in New Zealand is further illustrated by the formation of the Christchurch IWW Local in 1910. The city’s branch of the Socialist Party had no money in their social and general accounts, while the Literature Committee, which operated on a separate fund, had full coffers. Needing money for an upcoming election campaign, a motion was passed to join the three accounts together:

Unfortunately for this scheme the membership of the Literature Committee were anarchist to a man, and had no use for elections… Immediately the meeting concluded the Literature Committee went to work. By the small hours of the following morning they had completed their labours, which consisted of the ordering of over £100 worth of pamphlets and booklets… when they had finished, their finances were in the same state as the rest of the branch.42

Not surprisingly, at the following meeting the resignation of the Literature Committee was called for. The anarchists in question cheerfully left the Party and promptly formed themselves into a branch of the IWW. Some months later a rather large amount of wicker hampers packed with printed material started arriving from overseas—the second result of the Literature Committee’s nocturnal activities.

For those in power, the influence of the New Zealand IWW’s literature and its revolutionary adherents was no laughing matter. Faced by a militant working class and the eruption of outright class war during the strikes of 1912 and 1913, what one local Wobbly called the “deliberately organised thuggery by [Prime Minister] Massey and Co.”43 used violent means to quell the unrest, and the IWW itself. Striking workers faced naked bayonets and machine guns in the streets of Wellington, while special constables (volunteer, untrained additional police, mainly recruited from farm workers) revelled in cracking heads. The most militant agitators, including Wobblies, were arrested, or fled the country to dodge arrest.

Repression of the New Zealand IWW did not stop after the collapse of the strike in late 1913. The IWW and its members were monitored, scrutinised and silenced after the Great Strike and for the duration of the war that followed. Their literature and printed material became a primary concern for the state. By the time Hill’s ashes were divided into 600 packets and distributed worldwide there were no longer any IWW Locals in existence in New Zealand, only individuals scattered across the country.

Echoes of the IWW

After the defeat of the Great Strike, prominent Wobblies such as Tom Barker, Frank Hanlon and Harry Melrose moved on to more fertile shores, the harsh repression experienced during 1913 having “shattered the strong movement which Barker and others had built up.”44 The majority who did stay in New Zealand adapted to life without their own organization, and the increasingly stifling conditions of a nation heading towards an even larger confrontation—the First World War.

However the IWW in New Zealand was not dead, and there were certainly possible recipients of Hill’s ashes in the country in 1917. IWW and revolutionary socialist orators could still be found on street corners around the country leading up to and during the First World War, although no longer packing the punch they once had. Wobblies continued to organise during the war years—albeit quietly—either within other organizations, or on their own.

The Australian IWW paper Direct Action listed IWW contacts in the New Zealand cities of Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch up to 15 February 1915. The 1 October 1914 edition carried a news piece titled “From the Locals”, in which H J Wrixton, Secretary Treasurer of the Wellington Local, described the prevailing militarism and unemployment in the capital.45 Bill Murdoch, manager and publisher of the by-then defunct Industrial Unionist, was prominent in the Waterside Workers Union: “a big man with a big voice… there was seldom a meeting when it was not heard.”46 In 1915-16 Christchurch Wobbly-anarchist Syd Kingsford was still in the city working as a carpenter, though he kept his political activities quiet after the outbreak of war. Fellow Christchurch Wobbly Reg Williams did not, and was jailed accordingly. Other Wobblies set up “escape routes for conscientious objectors” during the war, “smuggling them in coal bunkers of ships to Australia.”47

In 1915 IWW stickers measuring two inches by two and a half inches were reported to frequent the Wellington wharves. Bearing the title “How to make your job easier”, these silent agitators advocated the direct action tactic championed by the IWW: the ‘go-slow.’ “Get wise to IWW tactics. Don’t be a pacemaker, someone has to be the slowest, let it be you… Fast workers die young. Live a long life. Join the Industrial Workers of the World, the Fighting Union.”48 In a cheeky swipe at conscription, one sticker was stuck in the middle of a National Registration poster.

Another silent agitator to appear in Wellington was Tom Barker’s infamous anti-war poster, To Arms!—a satirical poster calling on “Capitalists, Parsons, Politicians, Landlords, Newspaper Editors and other Stay-At-Home Patriots” to fill the trenches. Four copies of the poster were “smuggled across the Tasman... and pasted up outside the Supreme Court in Wellington,” causing the judge to suspend the court until the offending posters were removed.49

IWW and radical literature continued to find willing readers via well-known Wellington tailor and anarchist, Philip Josephs. One such reader was another Wobbly-anarchist, J Sweeney. On 3 November 1915, he wrote to Josephs from the small South Island town of Blenheim for one year’s subscription to Mother Earth and Freedom, anarchist journals from the United States and Britain respectively. As well as ordering literature, Sweeny asked Josephs to “remember me to the Direct Action Rebels in Wellington,” indicating there were still Wobblies active in the capital at that time. With typical Wobbly flair, Sweeney signed his letter: “Yours for Direct Action. No Political Dope.”50

Josephs’ distribution of foreign literature such as Mother Earth, his involvement with the IWW, and the fact that he was active for most of the war could have made him a recipient of Hill’s ashes. A Latvian-born Jew, Josephs had been actively involved in radical circles since his arrival from Scotland in 1904, eventually forming New Zealand’s first anarchist collective, Freedom Group, in 1913. A frequent speaker on topics such as ‘Anarchism and Outrage’, and ‘Socialism vs. Orthodox Religions’, Josephs also helped other ‘firebrands’ spread the word. “With the help of our anarchist friend and comrade P Josephs” wrote Barker in 1913, “I had 11 propaganda meetings in 14 days.”51

As well as organising speaking tours, it appears that in 1915 Josephs’ shop was, or had been, the Wellington head-quarters of the IWW. Any postage to the Local was received care of Josephs,52 as the New Zealand Police soon discovered. On 8 October both Josephs’ home in the Wellington suburb of Khandallah and his Cuba Street shop in central Wellington were raided by the Police. As well as “eleven newspapers in foreign print,” the Police found numerous IWW material, including “a number of unused official membership books, rubber stamps, and other gear used in connection with that constitution,” as well as IWW pamphlets.53 In one memorandum the Police stated: “it would appear from books found in Josephs’ possession that he obtains such literature from America.”54

However Josephs was not the only supporter receiving IWW literature in the mail at that time. Others around the country, and the Maoriland Worker, paper of the New Zealand Federation of Labour, regularly received copies of IWW newspapers Solidarity and Direct Action. But by 1917 the Federation had a deep-seated lack of sympathy for the IWW and unlike the labour movement in other parts of the world, failed to take up the cause of Joe Hill’s defence.55 The trial and execution of Joe Hill did manage to grace its pages, but only just—featuring in a mere eight articles (less than 500 lines). Most of them were straight news stories without editorial comment.56

This faint echo of IWW activity during the war is enough to suggest that there were Wobblies in New Zealand eligible to receive Hill’s ashes. Their activities, and wider working class objections to New Zealand’s involvement in the war, were also enough to set the repressive gears of the state in motion. For the National Coalition Government, headed by anti-labour conservative William Massey, socialist activity represented the threat of larger resistance to its involvement in the First World War, or even worse, a possible repeat of the growth experienced by militant labour leading up to the revolutionary moments of 1913. The government took measures to clamp down on any non-conformist activity it deemed seditious. “Any rhetoric which might encourage the development of strikes, conscience, or cowardice” was repressed,57 and the pretence of war conditions was used by the state to further cement its hold.

Seditious intentions

On 23 October 1914, the War Regulations Bill passed all of its readings in Parliament without a single word of debate. The resulting War Regulations Act empowered the executive branch of the National Coalition government to regulate all aspects of national life without reference to Parliament.58 During the course of the war, the regulations (initially of a purely military nature) were extended to cover dissent of the political kind. Individuals and organizations deemed capable of seditious activity were singled out and scrutinised—the activities of militant labour in particular.

Seditious activity was a category of elastic dimensions, defined by the state in such a way as to encompass a broad range of activity—including anything deemed critical of the New Zealand government, the war effort, and conscription:

Clause 1 provides as follows: ‘No person shall publish or cause or permit to be published or do any act with intent to publish or to cause or permit to be published any seditious utterance.’ ‘Seditious utterance’ is defined in Clause 3 of the Regulations as any utterance which is published with a seditious intention or the publication of which has seditious tendency.59

The final say on what exactly constituted seditious intentions often fell to Sir John Salmond, Solicitor-General of New Zealand from 1910-20. It was Salmond who widened the original definition of sedition laid out in the Crimes Act 1908, and the man behind the War Regulations Act. During his term as Solicitor-General, Salmond often “relied on common law authority to justify, in cases of necessity, state action which would otherwise be illegal.”60 It was his opinions to the Minister of Defence, the Police Department, and other arms of the state that sanctioned the censorship and repression of those in defiance of the War Regulations.

The Solicitor-General pursued sedition furiously, often in a way that blurred the lines of legality. “For Salmond, ‘legality’ ended when the State’s peril began.”61 If his advice to use special constables and naval forces against workers during the Great Strike, and the flurry of prosecutions during the war was anything to go by, ‘Salmond’s State’ had “a low threshold of pain.”62 As well as recommending that pacifists, unionists, and members of the Anti-Conscription League be prosecuted for ‘mischievous agitation’, Salmond ordered that the bells of Christchurch’s Lutheran Cathedral be melt-ed down on the grounds that they were made in Germany.

Rather than mere legal sanctions, such persecution under the War Regulations was clearly politically motivated. The Defence Department had earlier recommended the “wholesale arrest of agitators, leaders and resisters,”63 while Police or detectives could be relied upon to attend every public labour or anti-conscription meeting.64 Richard Hill, foremost historian of the New Zealand Police Force, notes that censorship “gradually increased in severity and in political rather than military significance.”65 Rather tellingly, those convicted of publishing information deemed valuable to the enemy were fined amounts ranging from 5/- to £10, while anyone who publicly criticised the actions of the New Zealand government was fined £100 or received twelve months imprisonment with hard labour. Of those convicted during the war for sedition, “almost all were socialist or pacifist.”66

When fiery unionist and Federation of Labour organiser Robert Semple was arrested for sedition in December 1916, Salmond recommended he be given “as long a term of imprisonment as is practicable.”67 Semple had told coal miners to resist conscription, which he believed was the “beginning of the servile state aimed not at the Kaiser but the working classes.”68 He was jailed for twelve months—his speech prompting the government to further the reach of the War Regulations Act and increase its prosecutions. (Ironically, Semple became a Cabinet Minister in the 1935 Labour Government and would later conscript New Zealand workers to kill their fellow-workers during World War Two).

As well as Semple, other labour leaders (including future Prime Minister Peter Fraser) suffered the long arm of Salmond’s law. Strikes in essential war industries were outlawed and defined as seditious. Socialist objections to conscription, Christians who argued that militarism was contrary to their religious beliefs, and sometimes, harmless banter between friends, were all defined as seditious. By the war’s end 287 people had been charged with sedition or disloyalty: 208 were convicted and 71 sent to prison.69

The New Zealand state was a world leader in using wartime regulations to political ends. As John Anderson, historian on the use and abuse of censorship during the First World War, points out: “the English government was more tolerant of criticism than the Massey administration, and did not readily initiate prosecutions for sedition.”70 In Australia, the Deputy Chief Censor:

requested that if anarchist literature was to be prohibited, action should not be taken by his office, because he did not think he was warranted in using his power against books which… were not objectionable from the standpoint of a military censorship.71

The New Zealand authorities, however, were quite happy to use the powers at their disposal to silence political opposition. When, in 1918, the British government advised that it was lifting export restrictions on British paper the Labour Leader, the New Zealand government “immediately urged that the prohibition be maintained.”72 Salmond and his cohorts insisted that they were using their discretion “in the public interest,” even though much of the suppressed material was of no military significance and “had circulated freely throughout New Zealand before the war.”73

Even after the end of the First World War the New Zealand government increasingly invoked the War Regulations in order to restrict the movement of socialists and their literature. The regulations “were entrenched, one year after armistice, by an Undesirable Immigrants Act, giving the state the power to ban entry to anybody deemed ‘disaffected and disloyal.’”74 Although the War Regulations were amended in 1920, it took a further 27 years for the Act to be repealed.

German-born children of the devil

Members of the IWW were even more of a target than pacifists or labour leaders, due to their advocacy of direct action at the point of production, their fostering of an oppositional working class counter-culture, and their radical critique of capitalism. As Joe Hill wrote: “war certainly shows up the capitalist system in its right light. Millions of men are employed at making ships and others are hired to sink them.”75 Not surprisingly, New Zealand’s Crown Prosecutor “repeatedly stressed the distinction between sincere objectors… and ‘parasites’, ‘anarchists’, and other IWW types.”76

One livid writer in the Otago Daily Times wanted “doctrines bearing the sinister IWW brand” to be stamped out:

The stuff is poisonous—to a degree revolutionary and even blasphemous… in a time such as this, when the struggle in which the nation is engaged emphasises the vital importance of harmony and efficiency… the blatant proclamation of pestilential revolutionary doctrines such as the IWW preaches is little removed from treason.77

As a result, a number of Wobblies were arrested and given maximum jail time under the War Regulations. ‘Rabid Orator’ and past Committee member of the Wellington IWW, Joseph Herbert Jones, was imprisoned for a speech made to 500 people in Dixon Street, Wellington. “I want the working class to say to the masters,” said Jones, “we don’t want war. We won’t go to the war.”78 During his court appearance Jones read a long and ‘inflammatory’ poem that received applause from onlookers in the court (the text of which, regrettably, appears to have disappeared without a trace). The judge was not impressed, nor did he share Jones’ view that all he had done was defend the interests of his fellow-workers. He was sentenced to twelve months imprisonment with hard labour.

Another militant to receive a twelve month sentence was Sidney Fournier. Fournier had caused “hostility and ill-will between different classes of His Majesty’s subjects” by opposing the Conscription Act and calling on workers to fight the only war that mattered—class war:

The view of us workers is that we should be fighting the only war in which we can at least become victorious— that is, the class war, or the war between the classes of people who own and control the wealth in all the countries that are now at war, and the people who labour and are exploited by the wealthy classes in all countries. The truth is this war is being forced on us by conscription, because as we know they take any opportunity that will produce them more wealth and give them more opportunity of oppression, until a peace could be brought about to their advantage, as they conceive it.79

When Fournier was arrested he was found to have in his possession a membership card of the IWW, a book on sabotage, a manifesto against conscription and other “anarchist literature.”80 This, and his speech, was enough to seal Fournier’s fate. On his release he was blacklisted and prevented from working on the Wellington wharves.

For a few in power the persecution and jailing of Wobblies was not enough. One Member of Parliament wanted to take a leaf out of Australia’s book and make it legal to deport individuals associated with the IWW. MP Vernon Reed asked in Parliament whether Prime Minister Massey had considered the provisions of the Unlawful Associations Amendment Bill introduced in Australia, “aiming at the destruction of the IWW and kindred institutions, and providing for the deportation or undesirables; and whether he will introduce into Parliament a measure having similar objects?”81 In reply, Massey stated that such a law was under consideration, although it was apparently never introduced.

When they were not being arrested or threatened with deportation, it seems the Wobblies were causing all sorts of problems on the home front—if one believes the newspapers of the day. In line with their fellow-workers around the world, Wobblies in New Zealand quickly became scapegoats for any kind of unscrupulous activity during the war. The press was quick to dub the IWW as ‘Hirelings of the Huns’ and tar workers involved in labour disputes with the IWW brush. As one Wellington poet put it:

If you need a scapegoat, don’t let it trouble you.

Put it all down to the I-Double W.82

In 1917 alone over 300 newspaper articles mentioned the IWW—next-to-none were favourable.83 A Wellington Waterside Workers’ Union member noted in the Evening Post: “it used to be the ‘Red Fed’ bogey; now it is the IWW.”84 In one bizarre article, ‘The Critic’ responded to an auctioneer’s listing of ‘famous IWW hens’ in the Manawatu Evening Standard with: “‘IWW hens?’ If these belong to the order of ‘I Wont Work’ they will probably get it where the Square Deal would like to give it to their human prototypes—in the neck!”85 When the shipping vessel Port Kembla was destroyed off the coast of Farewell Spit, one writer in the Ashburton Guardian put it down to pro-German sabotage, stating: “this Dominion is not by any means free of the noxious IWW element” and “this type of human being should be put out of existence on the first evidence of abnormality.”86

Such war hysteria, coupled with state repression, made it near impossible for New Zealand Wobblies to raise their heads above ground during the later years of the war, let alone celebrate the death of one of their martyrs. To do that, Hill’s ashes also had to evade the watchful gaze of Salmond’s State and the strict censorship of correspondence, a feat in itself.

Guardians at the gate

The ashes of Joe Hill would have arrived in New Zealand at a time when the state was on high alert and guarding against such incendiary material. Even though the packet destined for Australia was received without incident, the odds were stacked against Hill’s ashes making it into New Zealand. State surveillance of mail was in place ahead of Australia, and as early as 1915 the New Zealand authorities had specifically singled out literature by the IWW as a primary concern. International and domestic mail was thoroughly checked by a number of censors, and the post office boxes of suspected individuals were monitored for seditious content.

Even before the outbreak of war, steps were taken to give the state more power to halt the importation of ‘indecent’ literature into the country. The Customs Act 1913 allowed Customs officers with warrants to search any house, premises, or place suspected of harbouring uncustomed or indecent goods, including books and printed material. From then on Customs worked closely with the Post and Telegraph Department, and during the war, with the Police and Defence Departments.

As a way of keeping tabs on the influx of imported literature, Customs adopted a system of publication lists that compiled titles of banned books.87 IWW literature was soon added to the list. In 1915 MP John Hornsby raised questions in Parliament about the “circulation in this country of pamphlets of a particularly obnoxious and deplorable nature, emanating from an organization known as the Independent World’s Workers [sic]—commonly referred to as the IWW.”88 Hornsby asked whether immediate steps would be taken “to prevent the circulation through the post of the harmful publications in connection with the propaganda of this anarchial [sic] society—a society which openly preached sabotage, which meant in plain English, assassination and destruction of property?”89 The resulting Order in Council of 20 September amended the 1913 Customs Act, “prohibit[ing] the importation into New Zealand of the newspapers called Direct Action and Solidarity, and all other printed matter published or printed or purporting to be published or printed by or on behalf of the society known as ‘The Industrial Workers of the World.’”90

The response to this action was mixed. The New Zealand Federation of Labour hardly batted an eyelid at such brazen censorship of a fellow labour organization. The Maoriland Worker “failed to raise its voice in protest against the restriction and the only mention of it occurs parenthetically in the issue of 27 October 1915,” that is, over a month later.91 In Australia, Direct Action reported the law in typical IWW fashion. An article headed “Kaiserism in New Zealand” declared “the fact that the employing class of New Zealand found it necessary to exclude… IWW papers and literature… is the best tribute to the influence of direct action propaganda.”92 In another article, Direct Action predicted the increase of its popularity:

Since Massey & Co’s special law was enacted against ‘Direct Action’ there is a greater demand in New Zealand for the paper than ever, and if the law remains in force for a year or two we hope to have a wider circle of readers in New Zealand than even in Australia.93

Direct Action was certainly sought after in New Zealand—by the state. Two months after the Order of Council was in place, the Post and Telegraph Department reported the witholding of “14 single copies [of] Direct Action; 2 bundles [of] Direct Action;” as well as “6 bundles [of] Solidarity.”94 When Charles J. Johnson was arrested in 1917 and found to have “an enormous amount of IWW literature” in his possession, including three copies of Direct Action, the Chief Detective said “with the greatest confidence” that “this man is a danger to the community.” Johnson asked to be let off with a fine; the magistrate replied, “Oh, I can’t let you off with a fine in these conditions.” He was sentenced to twelve months imprisonment with hard labour.95

As well as doing his utmost to silence seditious utterances, Solicitor-General Salmond took a keen interest in halting sedition of the printed kind—especially that of the IWW. When Joseph Ward, the Postmaster General, asked Salmond whether the International Socialist Review fell under the Order in Council of 20 September, Salmond replied:

there is not sufficient evidence that the International Socialist Review is in any way connected with the Industrial Workers of the World. Nonetheless this publication is of a highly objectionable character advocating anarchy, violence and sedition. All copies of it therefore should without hesitation be detained…96

Salmond quickly added that the right to detain other objectionable material “is in no way limited by that Order in Council.” In other words, servants of the state had free rein to censor any literature they deemed seditious, whether it was written into law or not. He ordered that the International Socialist Review “should merely be detained” but “all IWW publications should be destroyed.”97

The likelihood that Hill’s ashes received such treatment is very high. It did not help that the packet containing Hill’s ashes was explicitly revolutionary in appearance—even the clumsiest of censors could not have missed “Murdered by the Capitalist Class”—unless, of course, it was hidden inside another envelope. Even so, the state knew the names of New Zealand Wobblies and their sympathisers, and did not hesitate to open and withhold their mail.

A public mischief and a public evil

While the Customs Act and the Order in Council only targeted IWW literature (such as newspapers and pamphlets), the correspondence of IWW members and other ‘subversives’ was also watched and withheld. The packet containing Hill’s ashes would very likely have been posted as correspondence to an individual Wobbly, making it a prime candidate for censorship. Whether on its own or inside another envelope, such correspondence to a monitored individual would have been gold to the watchful eyes of a censor.

“Immediately on the outbreak of hostilities a strict telegraph censorship was instituted,” wrote Postmaster Ward, and “a censorship of foreign postal correspondence was also established.”98 Domestic correspondence—both inwards and outwards—was closely monitored, so much so that some gave up on receiving mail entirely. On discovering that almost all of his mail (including Christmas cards) was being withheld, Charles Mackie, Secretary of the National Peace Council, advised his friends not to bother writing.99 According to official reports of the Post and Telegraph Department, 1,580 letters were withheld from delivery between 1914 and 1918.100

Both Customs and the Post and Telegraph Department had a number of censors working within their ranks, the latter including the Deputy Chief Censor, W A Tanner. But it was the military that managed censorship during the War. Tanner and other censors located across the country answered directly to Colonel Charles Gibbon, who was both Chief Censor and Chief of the General Staff of the New Zealand Military Forces. Postal censors were mostly officers of the Post Office and worked in the same building “as a matter of convenience”, but censors acted “under the instructions of the Military censor. The Post Office is bound to obey the Military censor.”101 The Defence Department’s earlier interest in the wholesale repression of agitators clearly carried over to agitation of the handwritten kind.

Salmond also took a keen interest in postal censorship, ensuring the monitoring of correspondence was carried out in full—whether it fell within his legal scope or not. Salmond often kept censored material sent to him, and regularly conferred with Gibbon on censorship matters: “I have been called upon to advise as to the censorship in New Zealand of correspondence and mail matter: and I have constantly acted as the legal adviser to the censorship.”102 However on one occasion his legal advice was deemed far from sound, causing an official enquiry into the censorship activities of the Post Office and the actions of Salmond himself.

The Auckland Post Office Enquiry, or the Bishop Enquiry as it became known, examined the censorship of correspondence pertaining to the Protestant Political Association (PPA), a sectarian religious organization headed by the vocal Reverend Howard Elliot. It was revealed that on the order of Salmond the post office box of this association was monitored, and all of its correspondence opened. In a memo to Colonel Gibbon, Salmond had gently instructed that the PPA’s “mischievous” material be censored: “perhaps steps could be taken by the Auckland censorship to see that all circulars… are examined, and if necessary, suppressed.”103 As a result a huge amount of PPA correspondence was opened and censored, so much so that the PPA, an organization with a wide influence and many followers, cried foul.

When cross-examining Salmond during the enquiry, Hubert Ostler, Counsel for the PPA and a past student of Salmond’s, hinted that the actions of his former teacher went further than mere legality:

(Mr H Ostler) Are we to understand that you are really the censor of New Zealand, Mr Salmond?

— (Salmond) No.

It sounds like it, does it not?

— No, I said I was the legal adviser.

But advise, of course, and when you advise the Military authorities they follow your advice, do they not?

— Usually.104

Ostler had no doubt that Salmond had overstepped his legal bounds. Yet, in the end, the enquiry officially sanctioned his censorship activities and that of the Post Office. Salmond did not escape lightly however, with some likening him to the Kaiser and saying he was “practically running the country.”105

In a stirring closing submission, Ostler remarked:

the action of the Solicitor-General in this case shows pretty conclusively that his practice of constitutional law is considerably weaker than his knowledge of it must be. In plain terms, I say the Solicitor-General’s action was unconstitutional and quite illegal. The people of this country, I say, will require the Solicitor-General or any other paid servant to act as a public servant, and in accordance with the law, not as a master and above the law, like a dictator.106

Yet act as a dictator Salmond did—sanctioned by the state as a necessity. “The existence of a state of war has made the establishment of censorship necessary,” wrote Massey in agreement.107 This state of war was not only directed at the Central Powers, but at the enemy within—elements perceived by the state as subversive and a threat to the running of their war machine. The IWW and its tactics of direct action represented a spanner in the works; printed material was one of its tools. Like the PPA, the correspondence of Wobblies fell victim to Salmond’s necessity.

Marked men in New Zealand

The New Zealand authorities had their eye on the correspondence of individual Wobblies. In 1915 Salmond asked Post-master Ward for “the names and addresses of the persons to whom these objectionable newspapers and magazines are sent.”108 As a result, New Zealand Wobblies—like Charles Mackie of the National Peace Council—became marked men for the duration of the war. One 1919 memorandum to the Minister of Defence noted that, on the advice of Salmond, “postal censorship is still being maintained on... inward correspondence from certain countries to specially marked men in NZ.”109 This special attention from the state ensured the mail of a number of Wobblies and their sympathisers was specifically stopped and opened, leading to raids on the homes of IWW members by Police, and—more often than not—imprisonment.

“The Johns and military pimps are on the look out for the correspondence of men known in our movement,” wrote William Bell in a letter that never reached its destination.110 Alongside detailed information on a number of Sydney Wobblies on trial for counterfeiting £5 notes, Bell’s letter described his attempt at trying to secure a dummy address “for the purposes of ordering leaflets without an imprint for secret distribution at this end of New Zealand.”111 Also mentioned in Bell’s letter was “a private meeting of picked trusted militants” due to take place at his bach [rural cottage] that week, confirming that Wobblies were still active in 1917 (albeit discreetly).112 Obviously Bell was not discreet enough. He was arrested and sentenced to eleven months imprisonment—his letter and earlier distribution of a pamphlet around Auckland having alerted the authorities to his activities. (During his hearing, Bell, like Fournier, provoked laughter in the courtroom. When the magistrate, referring to a comment in Bell’s letter, asked him what a ‘snide-sneak’ was, Bell replied: “A man who plays both ways. We have plenty in the Labor movement, unfortunately”).113

The letters of Wellington anarchist Philip Josephs, and anyone writing to him, were withheld after Salmond was alerted to orders for literature addressed to Emma Goldman, the US-based anarchist, feminist, and editor of Mother Earth. Salmond advised,

that the best course… is to arrange with the Post Office to have all correspondence addressed to Josephs whether within New Zealand or elsewhere stopped and examined. It may be that such examination will show that Josephs’ is an active agent of the IWW or of other anarchist and criminal organizations.114

One such correspondent was Syd Kingsford. “Please have enquiries made and report furnished regarding a man named ‘Syd Kingsford’, of 136 Tuam Street, Christchurch, who appears to be an agent in Christchurch for the distribution of anarchist and IWW literature.”115 Two Police intelligence reports show that he was under constant surveillance, while Colonel Gibbon made sure his correspondence was also censored: “the necessary action has been taken to have correspondence for… Syd Kingsford censored.”116

J Sweeney was another Wobbly-anarchist under the state’s spotlight. His November 1915 letter to Josephs (quoted earlier) never made it past the censor, who instead forwarded it to Colonel Gibbon so Police could find more Wobblies to monitor: “Herewith please receive a letter addressed to the anarchist P. Josephs. I forward it, as you may possibly wish the Police to know who are his correspondents in New Zealand.”117

The withheld correspondence of Sweeny, Kingsford, Josephs and Bell are but a few recorded examples of a larger targeting of Wobblies in New Zealand, “men whose correspondence it [had] been considered necessary to censor.”118 Although no record of the detention or destruction of Joe Hill’s ashes in New Zealand has been found, the monitoring of New Zealand Wobblies and their private correspondence points to a less than ceremonial fate.

Remains to be seen

The actions of Salmond and the censorship of correspondence illustrates a heightened level of surveillance and suppression by the New Zealand state during the First World War. Fearful of wartime industrial unrest and in order to avoid a repeat of 1913, the National Coalition government (and Solicitor-General Salmond in particular) used the pretext of war conditions to suppress any hint of labour militancy. As the visible expression of such militancy, the deeds and words of the IWW were targeted and suppressed, almost certainly including the little packet containing the ashes of Joe Hill.

Considering that Philip Josephs was one of the main distributors of IWW literature in New Zealand, that his correspondence was closely monitored on orders from Salmond, and that Salmond had previously ordered all IWW material to be destroyed rather than detained, the fate of Joe Hill’s ashes in New Zealand seems pretty clear. Regardless of whether they were sent to Josephs or another Wobbly in the country, it is almost certain that the packet containing the ashes of Joe Hill would have been stopped by one of the many censors, opened, and destroyed. Such action was within the guidelines set forth by Salmond and in keeping with the massive amount of material censored during the war.

When, at the conclusion of the First World War, Charles Mackie requested that his withheld material be forwarded to him, the Military’s Chief of Staff replied that the large quantity of confiscated material had been destroyed.119 “Most detained correspondence was destroyed,” confirms John Anderson, “except when it contained articles of value which could then be transmitted safely.”120 The lack of any record of the detention or transmission of the packet containing Joe Hill’s ashes lends weight to such an outcome.

As a result, it is highly likely that Hill’s ashes never made it beyond the national border. The monitoring of correspondence that existed in 1917 alone is enough to suggest that the ashes of Joe Hill never made it past state officials. That Sir John Salmond, War Regulations, Orders in Council, and various members of Parliament specifically targeted the IWW on a number of occasions surely sealed the deal. It would have been a small miracle for Hill’s ashes to see the light of day in the Dominion.

If Hill’s ashes miraculously managed to evade Salmond and his censors and some kind of ceremony had taken place, there are no oral or written records that recall such an event. There is no mention of any ceremony in the Maoriland Worker, even though the paper covered Hill’s execution and funeral. There is no mention of any ceremony in mainstream New Zealand newspapers, although the conservative Evening Post had covered the distribution of Hill’s ashes in Chicago and had previously jumped at the chance to publish anything IWW-related.121 No records, anecdotes or rumours of what happened to the ashes of Joe Hill in New Zealand have been uncovered. Of course there are always other possibilities, people to be interviewed, and archives to trawl, but it seems such historic silence indicates a job well done on the part of the censors.

It is possible that the packet of ashes received by Tom Barker in Australia could have contained another portion for his fellow-workers in New Zealand. Considering the transient nature of Wobblies at that time and his previous prominence in the New Zealand IWW, the American IWW may have wanted Barker to forward a portion of the ashes to his own contacts in New Zealand. If so, the ashes destined for New Zealand went up in smoke with its Australian counterpart.

Another alternative to Hill’s ashes being destroyed by the censors is illustrated by an example in the US. Toledo Wobbly George Carey did not release his portion of Hill’s ashes until 26 June 1950, and did so in a quiet ceremony on his own accord.122 Could the packet of Hill’s ashes in New Zealand have slipped through the state’s net undetected, quietly released by a New Zealand Wobbly fearful of repression if acting publicly?

Though this theory may please some (including the author), it seems unlikely. What is more likely is that the ashes of Joe Hill in New Zealand, like the New Zealand IWW itself, became a victim of state repression—targeted, suppressed, and denied the chance to “come to life and bloom again.” Sadly, the ashes of Joe Hill in New Zealand may have gone no further than the bottom of a state servant’s rubbish bin.

Jared Davidson is the author of This is Not a Manifesto: Towards an anarcho-design practice, Rivet, and other writings on design and anarchism. A poster-maker turned labour historian, Remains to be Seen is his first attempt at historical research. Jared is a member of the Labour History Project, designer of the Labour History Project Newsletter. He is also a member of the anarchist collective Beyond Resistance.

- 1. Joyce L. Kornbluh (ed), Rebel Voices: An IWW Anthology, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1964, p. 130.

- 2. Gibbs M. Smith, Joe Hill, Utah: Gibbs Smith Publisher, 1969, p.188.

- 3. Alec Holdsworth to Bert Roth, Bert Roth Collection, MS-Papers-6164-120, Alexander Turnbull Library (ATL), Wellington.

- 4. Fran Shor, ‘Bringing the Storm: Syndicalist Counterpublics and the Industrial Workers of the World in New Zealand, 1908-14’, in Pat Moloney and Kerry Taylor (eds), On the Left: Essays on socialism in New Zealand, Dunedin, 2002, p. 71.

- 5. Ibid., p. 69.

- 6. For an excellent exception see Franklin Rosemont, Joe Hill: The IWW & the Making of a Revolutionary Workingclass Counterculture, Chicago: Charles H Kerr, 2003.

- 7. Wallace Stegner, ‘Joe Hill: The Wobblies’ Troubadour’, New Republic, 1948, p. 24.

- 8. Mary Killebrew, ‘"I NEVER DIED. . .": The Words, Music and Influence of Joe Hill’, online at http://www.kued.org/productions/joehill/voices/article.html.

- 9. Kornbluh (ed), Rebel Voices, pp. 155-56.

- 10. Smith, Joe Hill, p. 15.

- 11. Ibid.

- 12. Kornbluh (ed), Rebel Voices, p. 127.

- 13. New Zealand Truth, 12 April 1919.

- 14. Eric Fry, Tom Barker and the IWW, Brisbane: Industrial Workers of the World, 1999, p. 27.

- 15. Verity Burgmann, Revolutionary Industrial Unionism: The Industrial Workers of the World in Australia, Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 1995, p. 119.

- 16. Smith, Joe Hill, pp. 179-190.

- 17. Barrie Stavis, The Man Who Never Died: A Play About Joe Hill; with Notes on Joe Hill and his times, Haven Press, 1951, p. 115.

- 18. New York Times, 20 November 1916.

- 19. Industrial Worker, 2 December 1916.

- 20. Kornbluh (ed), Rebel Voices, p. 157.

- 21. Melvyn Dubofsky, ‘Big Bill’ Haywood, Manchester University Press, 1987, p. 86.

- 22. Stegner, ‘Joe Hill: The Wobblies’ Troubadour’, p. 23.

- 23. Wallace Stegner, Joe Hill: A Biographical Novel, Penguin Books, 1990, p. 18.

- 24. Paul Dorpat, ‘Wobblies Unite’, Seattle Times, 22 June 1997.

- 25. Stegner, ‘Joe Hill: The Wobblies’ Troubadour’, p. 20.

- 26. Ralph Chaplin, Wobbly: the rough and tumble story of an American Radical, University of Chicago Press, 1948.

- 27. Kornbluh (ed), Rebel Voices.

- 28. Fry, Tom Barker and the IWW, p. 27.

- 29. Ibid.

- 30. Industrial Workers of the World, Proceedings, 10th Convention, 1916, Chicago: IWW Publishing Bureau, 1917.

- 31. Howard Robinson, A History of The Post Office in New Zealand, Wellington: RE Owen, Government Printer, 1964, p. 178.

- 32. Grey River Argus, 20 January 1908.

- 33. Erik Olssen, The Red Feds: Revolutionary Industrial Unionism and the New Zealand Federation of Labour 1908-13, Auckland, 1988, p. 132.

- 34. Industrial Workers of the World, ‘Industrial Workers of the World (subject)’, Bert Roth Collection, MS-Papers-6164-120, ATL, Wellington.

- 35. Mark Derby, ‘The Case of William E. Trautmann and the role of the ‘Wobblies’’ in Melanie Nolan (ed), Revolution: The 1913 Great Strike in New Zealand, Christchurch: Canterbury University Press, 2005, pp. 279-299.

- 36. Olseen, The Red Feds, p. 3.

- 37. Olseen, The Red Feds, p. 129.

- 38. Olssen, The Red Feds, p. 17.

- 39. Maoriland Worker, 25 August 1911.

- 40. Peter Steiner, ‘The History of the Industrial Workers of the World in Aotearoa’ in Industrial Unionism, Wellington: Rebel Press, 2006, p. 6. Online at http://www.rebelpress.org.nz/publications/industrial-unionism

- 41. Mark Derby, ‘A Country Considered to be Free: New Zealand and the IWW’, online at http://libcom.org/history/country-considered-be-free

- 42. ‘Anarcho-Syndicalism in the NZ Labour Movement’, NZ Labour Review, May 1950, p. 26.

- 43. Alec Holdsworth to Bert Roth, Bert Roth Collection, MS-Papers-6164-120, ATL, Wellington.

- 44. Derby, ‘A Country Considered to be Free’.

- 45. Direct Action, 1 October 1914.

- 46. Frank Prebble, ‘Jock Barnes and the Syndicalist Tradition in New Zealand’, Thrall, Issue 14, July/August 2000, online at http://www.thrall.orconhosting.net.nz/14jock.html

- 47. Derby, ‘A Country Considered to be Free’.

- 48. Colonist, 11 November 1915.

- 49. ‘NZ Wobblies’, Lecture Notes, Bert Roth Collection, MS-Papers-6164-120, ATL, Wellington.

- 50. J Sweeney to P Josephs, 3 November 1915, ‘Censorship of correspondence, P Joseph to Miss E Goldman, July-November’, AAYS-8647-AD10-10/-19/16, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- 51. Industrial Unionist, 1 October 1913.

- 52. Direct Action, 15 February 1915.

- 53. Report of Detective-Sergeant James McIlveney, 12 October 1915, ‘Censorship of correspondence, P Joseph to Miss E Goldman, July-November’, AAYS-8647-AD10-10/-19/16, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- 54. Memorandum for Superintendent Dwyer, 21 October 1915, ‘Censorship of correspondence, P Joseph to Miss E Goldman, July-November’, AAYS-8647-AD10-10/-19/16, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- 55. Norman D Stevens, ‘IWW Influence in New Zealand: The Maoriland Worker and the IWW in the US: 1913-1916’, 1954, Bert Roth Collection, MS-Papers-6164-120, ATL, Wellington.

- 56. Ibid., p. 12.

- 57. Paul Baker, King and Country Call: New Zealanders, Conscription and the Great War, Auckland University Press, 1988, p. 168.

- 58. Alex Frame, Salmond: Southern Jurist, Wellington: Victoria University Press, 1995, pp. 166-167.

- 59. Evening Post, 16 January 1917.

- 60. Alex Frame, ‘Salmond, John William – Biography’, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, online at http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3s1/1

- 61. Frame, Salmond: Southern Jurist, p. 167.

- 62. Ibid., p. 169.

- 63. Baker, King and Country Call, p. 156.

- 64. Ibid., p. 166.

- 65. Richard Hill, The Iron Hand in the Velvet Glove: The modernisation of policing in New Zealand 1886-1917, Palmerston North, 1996, p. 359.

- 66. Stevan Eldred-Grigg, The Great Wrong War: New Zealand Society in WW1, Random House New Zealand, 2010, p. 327.

- 67. Frame, Salmond: Southern Jurist, p. 174.

- 68. David Grant, Field Punishment No. 1: Archibald Baxter, Mark Briggs & New Zealand’s anti-militarist tradition, Wellington: Steele Roberts Publishers, 2008, p. 33.

- 69. Ibid., p. 36.

- 70. John Anderson, ‘Military Censorship in World War 1: Its Use and Abuse in New Zealand’, Thesis, Victoria University College, 1952, p. 246.

- 71. Ibid.

- 72. Ibid.

- 73. Ibid., p. 247.

- 74. Eldred-Grigg, The Great Wrong War, p. 457.

- 75. Kornbluh (ed), Rebel Voices, p. 131.

- 76. Baker, King and Country Call, p. 168.

- 77. Otago Daily Times, 13 September 1915.

- 78. Evening Post, 19 January 1917.

- 79. Maoriland Worker, 24 January 1917.

- 80. Evening Post, 16 January 1917.

- 81. New Zealand Parliamentary Debates (NZPD), 1917 p. 859.

- 82. ‘NZ Wobblies’, Lecture Notes, Bert Roth Collection, MS-Papers-6164-120, ATL, Wellington.

- 83. Online search of Papers Past for 1917: http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/

- 84. Evening Post, 5 February 1917.

- 85. New Zealand Truth, 7 July 1917.

- 86. Ashburton Guardian, 21 September 1917.

- 87. Paul Christoffel, Censored: A short history of censorship in New Zealand, Wellington: Department of Internal Affairs, 1989, p. 10.

- 88. NZPD, 1915, p. 469.

- 89. Ibid.

- 90. The New Zealand Gazette, 20 September 1915.

- 91. Stevens, ‘IWW Influence in New Zealand’, p. 8.

- 92. Direct Action, 9 October 1915.

- 93. Direct Action, 23 October 1915.

- 94. IWW Publications: Interceptions of., 15 November 1915, ‘Miscellaneous Administration Matters—Prohibited Literature—”Janes Fighting Ships”, Newspapers and other Printed Matters’, ACIF-16475-C1-98/-30/25/17, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- 95. Evening Post, 20 October 1917.

- 96. J W Salmond to Comptroller of Customs, 29 November 1915, Crown Law Office, Wellington.

- 97. Ibid.

- 98. Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives (AJHR), 1915, F1 p.4.

- 99. Baker, King and Country Call, p. 78.

- 100. AJHR, 1915-1919.

- 101. AJHR, 1917, F8 p. 8.

- 102. AJHR. 1917, F8 p. 3.

- 103. Ibid.

- 104. AJHR, 1917, F8 p. 45.

- 105. Frame, Salmond: Southern Jurist, p. 177.

- 106. AJHR, 1917, F8 p. 122.

- 107. AJHR, 1917, F8 p. 7.

- 108. J W Salmond to Comptroller of Customs, 29 November 1915, Crown Law Office, Wellington.

- 109. Memorandum to the Minister of Defence, 6 November 1919, ‘Communications—Censorship Of Correspondence to and from New Zealand—Instructions Re’, AAYS-8638-AD1-705-8/41/1, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- 110. New Zealand Truth, 14 July 1917.

- 111. Ibid.

- 112. Ibid.

- 113. Ibid.

- 114. J W Salmond to Commissioner of Police, 20 October 1915, Opinions – Police Department 1913-1926, Crown Law Office, Wellington.

- 115. Memorandum for Superintendent Dwyer, 21 October 1915, ‘Censorship of correspondence, P Joseph to Miss E Goldman, July-November’, AAYS-8647-AD10-10/-19/16, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- 116. Memorandum for Colonel Gibbon, 28 October 1915, ‘Censorship of correspondence, P Joseph to Miss E Goldman, July-November’, AAYS-8647-AD10-10/-19/16, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- 117. W A Tanner to Colonel Gibbon, 4 November 1915, ‘Censorship of correspondence, P Joseph to Miss E Goldman, July-November’, AAYS-8647-AD10-10/-19/16, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- 118. ‘Censorship of Correspondence, National Peace Conference, June 1915 – July 1920’, AAYS-8647-AD10-11/-19/33, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- 119. ‘Censorship of Correspondence, National Peace Conference, June 1915 – July 1920’, AAYS-8647-AD10-11/-19/33, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- 120. Anderson, ‘Military Censorship in World War 1’, p. 72.

- 121. Evening Post, 6 January 1917.

- 122. Kornbluh (ed), Rebel Voices, pp. 156-7.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| remainstobeseen.pdf | 5.47 MB |

Comments

Book and PDF now available! http://www.rebelpress.org.nz/publications/remains-to-be-seen

Mods: maybe we can attach the file to the original article? And change the text to '...is now available...'

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EuAzCFcAe8U

Footage of the book launch

Done. What a beautiful book, congratulations on the launch Jared!

It was a great launch, glad I managed to make it down for it Congrats again, Jared!

Congrats again, Jared!

Did the IWW end taking on any books to sell?

Glad you made it too Asher! Thanks for the kind words everyone.

@Chilli: I'll have to check with the publishers, but I never heard back from either the UK or US IWW. I'll keep trying