Capitalist and Commonist Social Media

What’s wrong with capitalism and capitalist social media such as Google, Facebook, Twitter, Weibo, etc. ? How would a commonist social media world look like?

With contributions and images by Carolina Cambre, Mario Haim, Teresa Alves, Han-Teng Liao, Matheus Lock, Tsai Hui-Ju, Jim Fearnley, Patricia “Jav” Zavala Gutiérrez, Shudipta Sharma, Marcin Koziej, Simon Schöpf, and Jolnas Jørgensen

tripleC contest in context of the publication of Christian Fuchs’ book OcucpyMedia! The Occupy Movement and Social Media in Crisis Capitalism

—

By Carolina Cambre:

This image encapsulates many of the worrisome issues around capitalist social media browsers and platforms such as Google, Facebook and others: they turn our communications and information into shiny hot air minions for sale. For one thing they are the epitome of un-freedom. Just like our information, not only is the balloon tethered, but it is perpetually available to be seen and manipulated on these capital propelled sites. We are seduced by the shiny and attractive venue, but it is a mirage of shimmering foil. Our information is perpetually open to examination, the single eye making it something that is seen more than something that is capable of seeing. Similarly the mechanisms and workings of capitalist social media browsers are hidden from view just as we, as users, become more and more transparent.

Because the control is on the other end of the rope, like minions we can only operate or communicate on someone else’s terms, and we have no options as to what happens to our information once shared via these channels. At the same time, we need to communicate and we are hemmed in by the ubiquity and prevalence of some forms of communication over others. And thus we must join the party to some extent or be on the wrong side of the digital divide.

A commonist social media would, for one, never change the rules, or standards or agreements without general consensus on the part of users. The commonist perspective would not allow data to be harvested from individual users, neither would it force users to reveal personal information. Needless to say, anonymity often legitimates harsh or unkind types of communication but a commonist platform would allow users to monitor and set their own rules within sub-groups. There should not be any control over communication whatsoever, just as if someone is walking down the street. Concerns over illegalities and illicit uses of the platform would be group administered, with measures in place for alerting authorities regarding abusive types of communication. There would have to be mechanisms for accountability and arbitration.

Set the minions free!

—

By Mario Haim:

What we experience today is a post-pivacy phenomenon: On the one hand, technology has driven us towards capabilities that enable us to work, shop, or socialize whenever and wherever we want. As this comes with a flaw, though, namely an information overload, algorithms help us to filter and prioritize the information “we want”. On the other hand, both the technological ressources as well as the algorithms mentioned are provided by capitalist companies from a few selected countries. Their services are based on connections within and aggregations of huge amounts of data. To come full circle, today’s technological advances are partly due to a sale of our own privacy as we are the sources of this data. Moreover, since this has become everybody’s daily life and business, there is no realistic opt-out option. Currently, we have to “sell” our privacy to capitalist companies in order to be part of our own society.

Hypothesizing about a communist social media world is not my field of specialty but it seems to offer me two possible extrema: A deconstruction or a deprivatisation of the mentioned capitalist social media companies.

To start with the latter, converting these companies into governmental or publicly owned NGO’s would most likely lead to a slow-down of their technological innovations. This, in my opinion, is due to two theses: (1) As the internet is a global phenomenon a complete commonist internet is highly questionable, and thus there would be other capitalist players left. (2) The ones driving the innovations, IT experts such as developers, would then be harder to employ as their high personnel costs could more easily be covered by capitalist companies. Furthermore, a deprivatisation would not solve the main post-privacy issue as I explicated in the beginning.

Ultimately then, a complete deconstruction of such companies reveals the full dilemma: Our Western society does not work without today’s technology anymore. We are reliant on the social networks and the internet that the capitalist companies offer us in a oligopolistic way. Global contacts, always-online mobility, the never-ending stream of available information, and, lastly, the algorithms that help us cope with all this data and, hence, decide whether our information is findable or not, are a one-way development.

Privacy, however, is a high price for that. Even worse, it seems, that it even isn’t the complete truth (i.e. compared to global surveillance). A commonist social media world would, in my opinion, solve the problem of the involvement of capitalist companies at the cost of technological innovation, which would probably lead to other (again, capitalist) providers. Hence, in the long run, it would not solve but move the problem.

—

By Teresa Alves:

As every social organism in this capitalist world, media is broadly subservient to the power of capital. As great part of capital in the world is concentrated in the hands of an elite, media is also dominated by a range of interests that reflect the concentration of income and wealth among the top earning 1%. Pragmatically, this means that mass media and social media are often a channel conveying thoughts, ideals and goals that are not representative of the other 99%.

For this reason, a commonist social media world would allow participation of the people across social classes, genders, ages, races, ethnicities and religions, allowing multicultural and transverse representation. Independent, alternative and free systems would improve the way people communicate among each other and with one another. Privacy laws and cryptography practices are extremely relevant, in order to build new forms of communication that are not controlled by the capitalist system and its flows of private interest. Let us build a world based on equality, freedom and justice with the help of social media that are actually controlled by the people.

—

By Han-Teng Liao:

Nothing is wrong with social media such as Google, Facebook, Twitter, Weibo, etc. except for the fact corporate social media for profit may prosper at the expense of the commonist vision that “social media of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the World-Wide Web”.

—

By Matheus Lock:

The question about what is wrong with capitalism and digital media is a tricky one because there are so many nuances and complexities that could lead one to analyse this relation in a very superficial way.

Before even to start thinking about a commonist social media, it is relevant to bear in mind that the development of digital technologies were only made possible because of the capitalist’s dynamics of production. In other words, immaterial capitalism and new digital technologies have become mutually interdependent. It means digital technology is not only a network structure that serves as a productive base to capitalism, but capitalists also invest in it with all their strength to extract as much value as possible; there is a movement of expansion of digital technology propelled by capitalism. Such a materiality presents an ambiguous potentiality.

On one hand, digital technology allows people to communicate, exchange information and knowledge, in order to create and share their own symbolic content, in a much faster, more accessible and dynamic way than previous communication technologies. This kind of technology enables people to engage in social interaction and in the production of their own political opinions and narratives. This potentiality of actions of the digital technologies introduces new practices, forms of sociability, political actors, groups, etc. There is a pluralisation of voices, collective production and political action.

On the other hand, there is a double movement made both by capitalism itself and by government towards complete control over digital technologies. It is well known that corporations such as Google, Facebook and Amazon track people’s consumer behaviour online to extract profit from it. They also try to limit collective creation of knowledge and sharing of information, controlling such production by restricting the flux of discourses and practices, and by lobbying for the privatisation and patenting of intellectual property. The second movement, the one made by governments, is as invasive and brutal as the one made by corporations. Nonetheless, as governments hold the monopoly of law creation and legal violence, their movement to control the flux of information and surveillance data is much more complex and deceiving than those put in practice by companies, which, in most cases have to respect some limitations imposed by sovereign states.

This is what can be labelled as a contemporary paradox; a paradox that presents all the potentialities and fragilities of digital media. For this reason it is very troublesome to state how a commonist social media world would look like. But we can risk toelaborate some basic principles of it:

* The internet should be kept neutral

* A common digital platform of social interaction should be posited outside capitalist relations of productions; which means that it should be an open source and open code platform created and maintained by anonymous peers

* All the information of the participants of this platform should be totally private

* This platform should be encrypted so as to make sure the information would be safe against government and capitalist surveillance.

—

By Tsai Hui-Ju:

Influencing everyday lives and changing social relationships online and offline, Facebook, which has 1 billion active users, has become the most influential social media channel. However, some critics have cautioned that, the more routine communication is mediated through online social media software, the more information technology companies oversee our digital trajectories. Facebook, a commercialized system, is not the panacea for human emancipation. Although we can see how social media helped people involve in the revolutions of the Arab Spring to communicate in real-time the places and times of events. Facebook, however, can be accused of invading its users’ privacy by the immoral practice of selling their personal data without their consent.

Today, Facebook users appear to operate freely but this freedom is in fact constrained by invisible controls. Facebook has been adept at hiding its complex privacy policy and its selling of personal data, a serious issue. In addition, Facebook’s strategies undermine the basic rights of its users. The social media site purports to offer a free service: chatting with friends, uploading personal photos, expressing comments, with not a cent changing hands. But Facebook is a company not a public service and this means that it has to sell something to make its profits.

To an extent, Facebook’s privacy policy gives more protection to big corporations and to the rich than to private individuals. It can be argued that the big corporations work in conjunction with Facebook whose users, under corporate surveillance, become consumers, consumers whose data, behaviors, and consumption habits are gathered and recorded ‘for accumulating capital, for disciplining them, and for increasing the productivity of capitalist production and advertising…’ (Fuchs 2012, p.141). Added to this is the fact that users’ personal background data is sold by Facebook and the day to day content, produced by its users, feeds into Facebook’s profitability.

Moreover, it is not only about the issue of ‘privacy policy’, but also reflects the problem of ‘surveillance’. These commercialised social media and ‘free’ online service always claim that they provide the open, free, and public space for everyone. However, Zuckerberg’s words could be the self-deprecating satire. He has given an interview on the ABC News ‘Nightline’ program arguing that ‘When you give everyone a voice and give people power, the system usually ends up in a really good place. So, what we view our role as, is giving people that power’ (ABC News Nightline, July 21 2010). Ironically, Zuckerberg’s words are a kind of propaganda for Facebook advocating democracy.

However, similar ideas such as emancipation, multi-polarism, empowerment, and grassroots movements have long existed on the Internet without the manipulation practiced by Facebook which has the potential to disempower people. So we can argue that people may have power, but Facebook itself is not empowering. Therefore, exposing Facebook’s strategies and analysing users’ interactions could help imagine ‘a new, public Facebook’ that would solve the current dilemma. In addition, the commonist social media could be done by several ideas, such as cooperatives, Public Service Broadcasting, local communities, and the national universities with public value.

References

ABC News (2010, July 21). Nightline: Inside Facebook. Retrieved August 30, 2013, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MSSeDJPVfrY

Fuchs, Christian (2012). The Political Economy of Privacy on Facebook. Television New Media, 13(2), 139-159.

—

By Jim Fearnley:

The major underlying premise of the Occupy movement is of a mutually-recognised community of interest among the “99%”, who are in alleged contention with the 1% who own the vast bulk of the world’s wealth. This is untrue, and the failure of a call to arms in the name of a traditional leftist proletariat, (implicitly composed of white, male, manual workers) will not be challenged by speculating an oppositional movement whose identity is so pluralist as to devalue the meaning of the term.

The New Left that developed before, during, and after the struggles of the 1960s represented a mixed blessing. ‘Struggle’ was siloed into partial identities based on ethnicity, culture, nationality, sex, sexuality, age, (dis)ability, etc., and thus recuperated by the equal opportunities agenda, while, however, analysing the specific experiences of distinct demographic groups. Class and economic status were routinely omitted from social taxonomies, which allowed for the recuperation of contestation, by, e.g., creating a black bourgeoisie to neutralise the radical threat of US street insurrections.

At the same time, the definition of the ‘impossible’ class was broadened to become far more contemporary and realistic. It now has the potential to embrace the relationship of the individual with the economy, perhaps best exemplified by the term ‘precariat‘. Those who have no reliable stake in the success of the economy thus become the new alienated class, including the redundant erstwhile bourgeois, displaced in the West by the encroachment of the digital economy and other developments.

However, the re-appraisal of the global economy in terms of its fundamental transformation over the last 20-40 years betrays an ongoing over-emphasis on Western societies. The concentration of the digital means of data production/storage in the hands of a few monopolistic players, indicates that traditional capitalist business is alive and well. Of equal concern is the extent to which the use of data (and traditional labour) as commodity enables a form of self-managed enslavement, which presaged and runs alongside ‘intern culture’, where individuals voluntarily work for free, sharing information about their consumer preferences and trialling new versions of software, for example.

Equally, alleged enemies of transnational ‘surveillance capital’, confuse changes in the form of commodities and their production (i.e. from ‘things’ to ‘services’ and ‘ideas’) in the West with a (non-existent) change in social relations. Because Western production now focuses on artefacts, affect, and communication does not mean this is the only terrain on which social struggles can be waged.

Indeed, it can be argued that an academicist prioritisation of mind over body (as beloved by ‘left’ and post-modernist schools as any other) repeats the division of labour expressed in all bourgeois revolutions, where consciousness is brought to us miserable serfs, thrashing about in ‘meatspace’. However, for the physical critique of the State to be meaningful, it will have to supersede symbolic demonstrations of ‘anger’, and thus diminish the notional 99% power base.

—

By Patricia “Jav” Zavala Gutiérrez:

Both Aldous Huxley and George Orwell, cared about the future of capitalism, and the society. Both feared that future. And yet both for different, and apparent contradictories, reasons. Now we can be certain that both got the issues right. The present economic politics it is nothing more that the old tramp but with new clothes.

Big-money people have assumed the old role of a monarchy, and worse. The different ways to obtain money and power have changed from the open terror and violence and scams to democracy and media. The oppressor justifies its rhetorical movements and hides its real intentions, not by using the theological justification for monarchy but for the delusion of democracy, and the corresponding manipulation of the media.

In this way, whoever is trying to uncover these facts is treated as a madman, an enemy of freedom and society. The victim is not only subdued, but the proper language for his condition of victims is taken away, cutting from the very beginning any possibility of changing the situation. Capitalists provide the money necessary in order for the politicians to win elections. This in turn creates laws that benefit capitalists. They frequently accept bribes for governmental contracts, which in turn make the rich and capitalists richer, and so everyone within the dominant class is happy. They are the ones who own democracy in our countries. And social media follows that pattern.

There is no need to encourage civil virtue: entrenched levels of corruption limit the possibilities of real change of the government. And corruption not only implies taking bribes, but also the lack of accountability. It is easier to cheat the public, to ask or force social media to signal whoever is trying to change things, than try to make the right decisions. Public and health services have suffered cuts for the sake of the economy, yet these same time laws and government rules have barely touched capitalist interests: While governments and normal people have been forced to be deprived for the last twenty years, in the same period capitalists have seen their fortunes grow at historical levels. There is a strong reluctance to question the fundamental basis of our culture and society, which in itself is crippling free enquiry, and freedom of speech, hiding the consequences of capitalism. Capitalist social media backs all of this. We are thus tracing the path of ancient Rome. The class war that Marx described is not over, yet. It’s still there, and more dramatic and violent than ever.

Is there any pathway out of this maze? I think education and honest and active politic actions could be a starting point. I don’t think they would/could be sufficient, but we have to start from somewhere. And a problem is that social media has to be involved in the creation of revolutionary class-consciousness. If that is possible then we can find ways that make sure that we are on the right track to the future.

—

By Shudipta Sharma:

The main problem of capitalism is that it always tries to ensure profit. Even in the name of social responsibility it tends to do its business. Capitalist media industry is not different. From the print media to today’s new media we are experiencing the same scenario. Though it always tries to represent itself as a pro-people social institution that makes a bridge between people and the government, we see, the main goal of the capitalist media is to making money. People are the second priority for them. They sell their audiences to their advertisers and tend to create a consumer culture.

On this background, many people think, social media such as Facebook, Twitter, Weibo etc. come as a boon for general people. Social media platforms also paint themselves that they facilitate an interactive space for all to express their opinion, views, feelings, emotion, etc. on any issue freely. They also try to get the credit of creating a real public sphere. However, we are noticing that the web 2.0 technology provides the capitalists a new opportunity to do business and they are utilizing it. In the name of public sphere they are also doing business. This new technology gives them a unique opportunity to exploit unpaid labour. Their unpaid users are acting as prosumer who creates and consumes their own content. Paid staff is merely managing the whole activities. Moreover, in many senses, social media platforms are a threat to people’s privacy that was almost secure in the traditional media era. In fact, social media platforms instigate its users to provide their personal information so that they can do business. The capitalist social media platforms record every single activity of its users. Without users’ concern they sell this information to advertisers, which facilitates targeted advertisements. In fact, their privacy policy allows them to do this. But most of the users are not aware of it.

Social media also help the authorities to create a surveillance society, where everything is being watched by ‘Big Brother’. Social media platforms provide its users’ information to the law enforcing agencies and help them to monitor anyone’s activities. So, we can say that users are not safe at all on this type of social media platforms. Moreover, their policy also allows them to deactivate any account whenever they want to. This is also a threat to users’ freedom and information. That is why, I think, this type of social media platforms are not pro-people, but rather a threat to people’s privacy.

So, I think, a commonist social media should be developed and maintained by its users. It would not store any information and there should not be any advertisement. It will be run with the help of users’ donations. It will be true a public sphere where anybody can join and express whatever they think. Users’ privacy will be strictly protected there. Nothing will be provided to the law enforcing agencies in any case.

—

By Marcin Koziej:

Current social media are placing too much focus on the individual. Users are nodes who make up the networks, and their digital relations are forming its links.

This is turning networking into an ego game, where users struggle to win by being a better node: tweet more, share more, and make a perfect impression. It is also creating index authorities [1], where nodes with more links (followers, friends) are holding a position of power. Such a mechanic is turning communication into competition, where the goal for each individual is to accumulate attention for him- or herself only, so s/he can be looked at and rewarded with likes and retweets.

Commonist social media, on the contrary, should turn communication into collaboration, by making various commons and common issues a basic building block of the network. When they would become nodes, relations, dependencies, and flows between them would become links. They would become focal points of attention, and us, humble users, would finally be just defined not by what we show off online, but what we participate in

[1] A term taken from Mathieu O’Neil, Cyberchiefs: Autonomy and authority in online tribes, 2009, Pluto Press, London

—

By Simon Schöpf:

Capitalist social media plays the game of distraction. The more we engage, the more we click, the more we ‘like’, the more we comment, the more we wipe our thumbs, the more money for the digital monopolies, paid by advertisers. Frankly, this distraction does get annoying in everyday life.

In The Shallows, Nicholas Carr presents a lot of scientifically backed research on the increasing fragmentation of our consciousness and argues that the web distorts our ability of ‘deep reading’, constantly throwing little snippets of information at us and not allowing the user to engage with one topic, at length and in depth. The “media work their magic, or their mischief, on the nervous system itself”, Carr says. How about extending this phenomenon to a new level and claim that capitalist social media, on another layer, also influence our ability of ‘deep listening’ and drastically further even, ‘deep being’? Does anyone remember the times when you could go to a rock concert or merely sightseeing and were still able to see the stage or the sight? Often today, the objects are somewhat hidden behind a fence of glowing devices, recording action just to never look at it again, just for the sake of recording. Not making use of the possibility to ‘share’ seems like ‘losing out’ by not letting everybody know what amazing things you are doing right now. And even though we end up not sharing our experiences anyway, the mere feeling of needing to share is what distracts from the real experience. We were made the main players in the game of distraction.

Communist social media would play a different game. It would not be financed primarily by advertisers, so it would not be primarily interested in distracting our minds from everyday life for the sake of likes and thumb-strokes. It would allow us to again re-gain our ability to think deeply, to listen deeply, to be deep. Such media would focus on the true needs of users that can be found in communication, co-creation, and co-operation; not in constant distraction.

Heidegger calls our ability to engage in meditative thinking the very essence of our humanity; “The frenzied-ness of technology threatens to entrench itself everywhere”, he says. Everywhere? We better act, then.

—

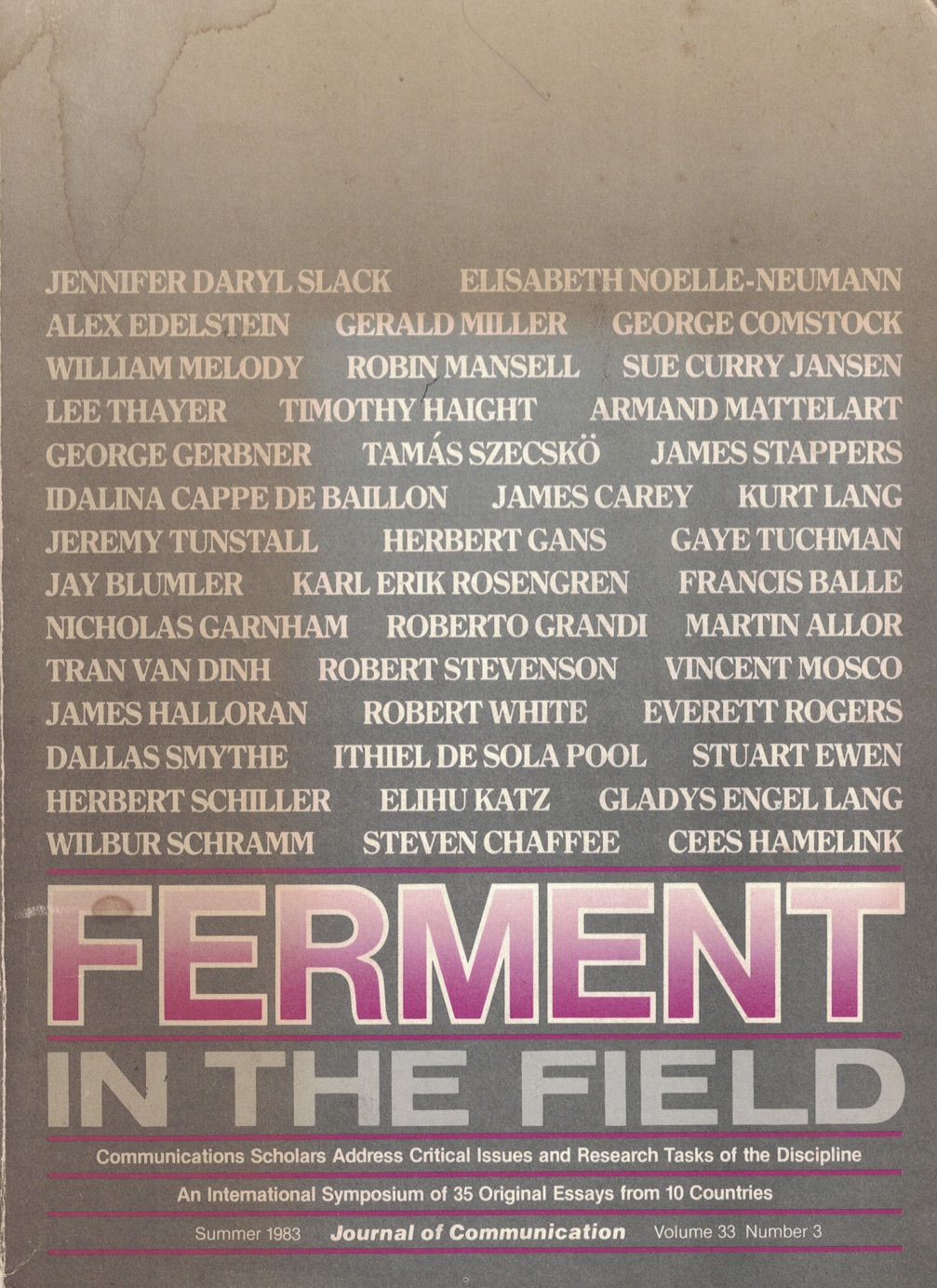

On Common Ground

By Jonas Jørgensen:

Last week it was reported in the media that more than fifty so-called ‘geoglyphs’ had recently been discovered in the northern Kazakhstan (Cf. http://www.livescience.com/47953-geoglyphs-in-kazakhstan-photos.html). These figurative or geometric ancient land art structures, that range from 90 to 400 meters in diameter, are usually hard to see from the ground, but known from other parts of the world as well, notably the Nazca region of Peru. What was novel about the recent discovery in Kazakhstan, however, was that, according to the researchers, it had been made by using images from Google Earth.

About a month ago, a different story was making the rounds on social media. ‘Google Maps Has Been Tracking Your Every Move, And There’s A Website To Prove It’, the headline declared, and the article further elaborated: ‘Today, Google is tracking wherever your smartphone goes, and putting a neat red dot on a map to mark the occasion.’ (Cf. http://junkee.com/google-maps-has-been-tracking-your-every-move-and-theres-a-website-to-prove-it/39639).

Vogelfrei (literally ‘bird free’, but meaning an outlaw (a person without legal rights) in German) was the term Marx used to describe the proletariat, created with the decline of feudalism through ‘the forcible expropriation of the people from the soil’. Some researchers have suggested that the geoglyph markings made on the soil have a ritualistic and cultic origin, while others think that ancient tribes used them to mark off ownership of land.

The image I have included shows a portion of my tracking data from Google from the last thirty days that I have reproduced manually. It is superimposed on a creative commons licensed photo of the hummingbird geoglyph at Nazca (Image credit: Irina Callegher, “Famous hummingbird, Nazca lines,” via Flickr. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0), as the images of the Kazakhstan geopglyphs are all copyrighted by DigitalGlobe, the company that supplies Google Earth and Google Maps with their images.