A brief overview of the Luddite movement: militant textile workers in the UK who fought against job losses and deskilling brought about by the industrialisation of the industry.

The Luddites were textile workers in Nottinghamshire, Yorkshire and Lancashire, skilled artisans whose trade and communities were threatened by a combination of machines and other practices that had been unilaterally imposed by the aggressive new class of manufacturers that drove the Industrial Revolution.

In Nottinghamshire, where the Luddite attacks began in November 1811, the ‘framework-knitters’ or ‘stockingers’ who produced hosiery using stocking frames had a number of grievances, including wage-cutting, the use of unapprenticed youths for the same purpose, and the use of the new ‘wide frames’, which produced cheap, inferior quality goods. The fact that the stockingers objected to the latter because they were destroying the reputation of their trade illustrates the conflict between skilled artisans and the free-market/industrial mindset. The undermining of wages and the use of unskilled labour clashed with the existing ‘social contract’ between workers and masters that prescribed ‘customary’ wages that had been maintained by tradition over many decades. Oany of the smaller master hosiers supported the stockingers’ demands and some are thought even to have refused to name to the authorities men they knew were involved in the Luddite attacks.

In Yorkshire, the Luddites were led by the croppers, highly skilled finishers of woolen cloth who commanded much higher wages that other workers, and were highly organised. For the past decade they had petitioned Parliament to enforce obsolescent legislation enforcing apprenticeship, and against ‘gig mills’, machines invented in the 16th century which could do part of the croppers’ job. But the greatest threat to them was a more recent invention, the hated shearing frame which eventually almost entirely displaced them over the next ten years. In 1809, under pressure from the manufacturers, Parliament repealed all the old legislation, thus removing the artisans’ last hope of redress for their grievances by legal and democratic means.

The Lancashire cotton weavers and spinners were, like the stockingers, mainly outworkers, producing cloth on hand looms in their own homes and paid by the piece. Their overall conditions and status as artisans had been eroding for several decades, partly as a result of a huge influx into the trade of unapprenticed workers, many of whom had been forced off the land by the Enclosures. The factory system, with its vast mills and steam-powered looms, its long hours of dangerous work and its cheaper cloth that undercut the cottage weavers, was exacerbating their decline.

All these groups of artisans were resisting the ways in which the industrial system degraded the dignity of their trades, turning them into mere factory 'hands'. Although they were outworkers, paid by the piece, for a long time they had managed to maintain a modest and frugal lifestyle in which they had their own independence and other sources of subsistence, eg their own vegetable gardens, and a strong community ethic of mutual aid. This world is sometimes romanticised, and had already been destroyed to a considerable extent by the Enclosures: no doubt their life was far from idyllic. But the strength with which they resisted the industrial system is a measure of how much better it was compares to the harsh new world of factory wage slavery.

Revolution, war, starvation

In addition to the economic and technological changes which produced Luddism, the period after 1789 was one in which the communities of the emerging working-class were radicalised by the Revolution in France and the writings of Tom Paine, etc. The strongholds of radicalism were Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire and Lancashire where pro-Jacobin groups operated in secret. After the passage of the Combination Acts of 1799 which banned all trade union organisation, these too were forced underground, and the Luddite groups grew naturally from these two roots.

In the first decade of the 19th Century the cloth trades were depressed due to the wars with France, and unemployment often meant destitution and starvation. Throughout this period, in addition to the Luddite attacks there were many food riots throughout the North of England, which were also partly due to high food prices caused by poor harvests. In the period before 1811, many petitions to Parliament, asking for help for starving weaving and framework knitting communities were ignored by Tory Governments which were obsessed with the then-new laissez-faire economic doctrine. When the Luddite explosion came, the willingness of thousands of people to risk hanging or transportation to Australia is a measure of the desperation of those communities, and their feeling that they had nothing to lose. Those who insist that the Luddites should have realised that machines would eventually bring progress and prosperity, should ask themselves what they would have done to save their families in the dire situation that the Luddites faced.

Machine breaking

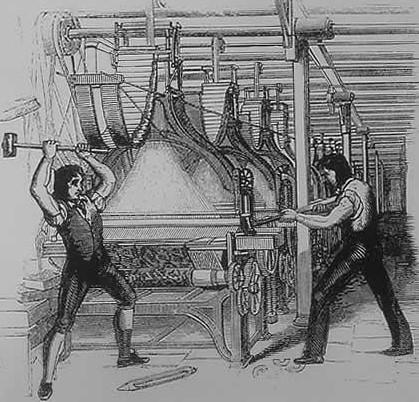

The Luddite uprising began in Nottingham in November 1811, and spread to Yorkshire and Lancashire in early 1812. The Luddites’ main tactic was to warn the masters to remove the frames from their premises. If the masters refused, the Luddites smashed the machines in nocturnal raids, using massive sledgehammers. It is widely agreed that the Luddites’ leader, in whose name their letters and proclamations were issued, known as ‘General Ludd’ or ‘King Ludd’, did not actually exist. The name is said to derive from one Ned Ludd, an apprentice weaver, who some years earlier smashed a loom in a rage at his master who had beaten him.

Machine breaking had occurred sporadically in disputes between workers and owners many times before, but the Luddites were much more systematic and organised. In Nottinghamshire, the Luddites played on the Robin Hood myth: as one of their songs had it,

‘Chant no more your old rhymes about bold Robin Hood,

His feats I but little admire,

I will sing the Achievements of General Ludd

Now the Hero of Nottinghamshire’

The Luddites were a secret society which administered oaths of silence to ‘twist in’ new members. These were extremely effective in preventing capture: for a year, despite flooding the Midlands and North of England with spies, and more troops than were currently fighting Napoleon in Spain, the authorities made only a few arrests of minor players. Spies were generally unsuccessful because all the members of Ludd’s army were well known to each other as fellow stockingers and croppers. Their success in evading capture, bemoaned in many reports to the Home Office, was due to the extremely strong support of the their communities, who were suffering with them and had been united against the manufacturers. Lord Byron, a Nottinghamshire landowner, mocked the efforts of the troops:

‘Such marchings and countermarchings!… and, when at length, the detachments arrived at their destination, in all 'the pride, pomp, and circumstance of glorious war,' they came just in time to witness the mischief which had been done, and ascertain the escape of the perpetrators, to collect the . . . fragments of broken frames, and return to their quarters amidst the derision of old women, and the hootings of children.’

Although there were already many laws on the statute books making the Luddites’ activities capital crimes, in February 1812 the Government passed the Frame Breaking Act, which specifically introduced the death penalty for frame breaking. It was during the Parliamentary debates about this bill that Lord Byron made his famous speech in defence of the Luddites. The Act, together with the influx of troops and spies seems to have brought an end to the attacks in Notttinghamshire at around this time, although this may also partly have been because there were not so many frames left to break, and because many of the hosiers had agreed to restore wages to their former levels.

In Manchester, a warehouse of a manufacturer who used power looms was burned down in early February 1812. In general, the Lancashire Luddite attacks focused on the large mills and some took place in the daytime as part of large-scale food riots involving hundreds of people and sometimes involving direct confrontation with soldiers. Several large mills in the Manchester and Stockport districts were burnt down and as many as 50 people, including women, may have been killed in the these incidents, which continued from February to May 1812.

Rawfolds MillIn the West Riding of Yorkshire, cropper attacks began in January 1812 and their nocturnal raids were highly successful in destroying frames in the smaller workshops and evading capture. However, resistance from some of the larger mill owners, supported by magistrates was stronger here. The most famous attack, by around a hundred men on William Cartwright’s Rawfolds Mill in April 1812, described in Charlotte Brontë's Shirley, was unsuccessful, since Cartwright was aware of the Luddites’ plans and the troops that he had installed in the mill killed two of the Luddites. This incident is generally seen as the climax of Yorkshire Luddism. After these deaths, and the outrage they caused among the Luddites' supporters, for the first time the Luddites turned to assassination. They failed with Cartwright, but succeeded in killing William Horsfall, another large mill owner and an outspoken anti-Luddite. Over the summer of 1812 the Luddite attacks on machines declined, and some Luddites turned to night-time raids on armouries, in the hope that a general armed insurrection could be mounted. In October 1812 the Authorities finally arrested George Mellor and two others for the murder of Horsfall. They and 14 others were hanged together at York in January 1813.

By the end of the uprisings thousands of frames, a significant proportion of the total number in England had been smashed. And although it is often argued that the Luddites effects failed, it seems that in Nottinghamshire many of the master hosiers were sufficiently intimidated that the wide frames were not widely used for some years and wage levels were considerably restored. Although Luddism was finally defeated by violent state power, it may have been the nearest Britain has come to revolution since the 1640s. As noted above, it happened when it did because of the coming together of a number of factors, only one of which was the introduction of machines that displaced labour. The other causes may be summarised as the imposition of the new free-market/industrial regime and the tearing up of the whole 18th century social contract by the manufacturers. The machines were perhaps the sharpest edge of the new regime and were chosen as targets because they symbolised the power of the new masters. The uprisings can be seen as the last gasp of the old order, a general howl of protest against the Industrial Revolution.

Although organised Luddism ended in 1813, there were sporadic attacks of machine breaking over the following few years, and in the 1830s the South of England saw similar protests against threshing machines, know as the ‘Captain Swing Riots’. Other countries also saw less well organised attacks of machine breaking, but for the rest of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, the Luddites were largely forgotten. It was only in the 1950s, on the brink of a new technological revolution that its publicists began using the term ‘luddite’ as a term of abuse for those who raise concerns about, or do not immediately embrace new technology.

After the crushing of their revolt, the factory system, with all its horrors could no longer be resisted and generations of working class men and women and children were forced to work 12 hours or more per day for a pittance, their lives running according to the rhythm of the machines, their deaths often caused by them.

Above all, the destruction of the Luddites by the State established the principle that industrialists have the right to continually impose new technology, without any process of negotiation, either with the people who have to operate it or with society at large. It is this principle and the resistance to it that have led in our time to backlashes against the corporate imposition of technologies like genetic engineering, nuclear power and now ‘geoengineering’.1