I’m sorry to say that the great British novelist and television writer David Nobbs died a few days ago.

As many of you will know, David was one of my favourite writers. I first read his novel The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin in the mid-1970s, shortly after the TV series of the same name had started airing on BBC 1. It had the most profound effect on me. It’s no exaggeration to say that everything I try to do in my own writing - the combination of comedy and melancholy, of social commentary and farce - can be traced back to my encounter with this one novel. In a just world, it would now be published as a modern classic, and Reginald Perrin would be recognised as the British equivalent of Updike’s Rabbit Angstrom, or Richard Ford’s Frank Bascombe.

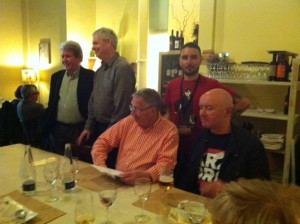

I was lucky enough to become friends with David and even luckier to have him adapt one of my own novels, What a Carve Up!, for radio - which he did brilliantly. We made several appearances at festivals together and these pictures are a memento from a trip we made to Barcelona last year.

This particular trip came about because a Spanish edition of The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin had just appeared, and a very bright young Spanish critic and novelist, Kiko Amat (the bearded guy in these pictures) had spotted the affinities between David’s book and What a Carve Up!. Kiko was running the Primero Persona festival and wanted to put on an event with the two of us. The idea was that we should be sitting on a bench as if we were in a railway compartment, with the British countryside back-projected behind us, and would have an informal, 45-minute conversation about British satire and comedy. Of course, this being Spain, we didn’t get on stage until about midnight, by which time David was extremely tired and we were both a bit the worse for Rioja. To compound the situation, the next event was a conversation with one of Spain’s most popular singers, Manolo Garcia, and the audience consisted largely of his fans, who probably had no idea who we were. David loved the absurdity of all this, as he loved absurdity wherever he found it. Earlier that day we’d met up with Irvine Welsh at a restaurant (David and Irvine always got on very well, and had tremendous mutual respect), then David and I walked down to the Rambla de Mar for a long, late lunch. He was my parents’ age but I never felt any sense of a generation gap, and this is my final, clearest and best memory of him: sharing a seafood paella together that afternoon, sitting beside the Mediterranean, and talking for hours about (what else but …) comedy.

(David and Irvine always got on very well, and had tremendous mutual respect), then David and I walked down to the Rambla de Mar for a long, late lunch. He was my parents’ age but I never felt any sense of a generation gap, and this is my final, clearest and best memory of him: sharing a seafood paella together that afternoon, sitting beside the Mediterranean, and talking for hours about (what else but …) comedy.

Last week my agent received an email from a reader in Bristol which came directly to the point: ‘Please would you ask your client Jonathan Coe to update his website? It seems untouched since January.’

Well, it’s a fair cop.

I will be honest and say that I don’t find blogs very easy to write – also, I would rather be sitting down to write my new novel - so I’ll make this one pretty functional and just bring readers up to speed with some things I’ve been involved with this year which may have gone under their radar.

An ebook of my short stories came out in June. It’s called Loggerheads and Other Stories  and you can buy it from either Amazon or Penguin. It’s quite short (74 pages) but there are some previously unpublished items in here and people might be interested in one or two of the stories which forge connections between Expo 58 and The Rain Before It Falls.

and you can buy it from either Amazon or Penguin. It’s quite short (74 pages) but there are some previously unpublished items in here and people might be interested in one or two of the stories which forge connections between Expo 58 and The Rain Before It Falls.

In July at the Collisioni Festival in Barolo I finally went public with my music, in a short concert with four wonderful Italian musicians led by Massimo Giuntoli. We played an hour’s worth of my tunes as well as a couple of ‘Canterbury’ standards – Alan Gowen’s ‘Arriving Twice’ and Pip Pyle’s ‘Fitter Stoke Has a Bath’. You can see some photos from the rehearsals and performance at Massimo’s website here.

In September I made my first ever visit to LA to do an interview about Expo 58 with Michael Silverblatt for his famous NPR programme Bookworm. It was a great interview and you can listen to it here.

Last month shooting started in France on Michel Leclerc’s feature film adaptation of La Vie très privée de M. Sim. I’m thrilled that the great Jean Pierre Bacri is taking on the title role. I stopped over in Paris recently to have lunch with Michel who showed me some early rushes from the closing scenes of the film – they looked wonderful.

That’s about it, although I should also apologise for being absent from the messageboard recently. I’m deep into the writing of my eleventh novel – provisionally entitled Number Eleven, so no great challenge for my translators this time – and am trying to maintain focus on that. I don’t want to give up interacting with my readers altogether, though, so recently I did something I swore I would never do, and joined twitter. This was actually the result of a rather alcohol-fuelled lunch with my friend Philippe Auclair, who bet me that if I joined twitter I would have 5,000 followers in two days. (Four months later I have less than half that, but never mind.) Anyway, if you want to follow me I’m @jcoescrittore, and nowadays that’s probably the best way of getting a quick answer out of me about one of my books.

The Festival De Cinéma Européen des Arcs takes place every December in the French Alps high above the little town of Bourg-Saint-Maurice in Haute-Savoie. It is the brainchild of two men, Pierre-Emmanuel Fleurantin and Guillaume Calop, who now live in Paris but were born nearby and whose love for the region is matched only by their love for cinema. The mountain resorts which form Les Arcs are well known for their winter sports and one of the principal aims of the festival is to combine the pleasures of skiing with film-watching.

As a confirmed non-skier, this aspect of the festival is not so appealing to me, but even so, I’ve always loved Alpine scenery, and will always jump at any excuse to get out of London in the run-up to Christmas, so when I was invited to be on the jury for this year’s festival I didn’t hesitate for long. And of all the things I did in 2013 – which turned out to be a pretty busy year, all told – this was certainly one of the most rewarding.

I’ve been on film juries before, at the Venice, Sitges and Edinburgh festivals, and it can be a frustrating experience if you find yourself at odds with the other jury members. But this was the most harmonious bunch of people I’ve ever worked with. Credit for that must largely go to the wonderful actor/director Nicole Garcia, who was our president, but I must also thank all the other members – Anais Demoustier, Cédomir Kolar, Anna Mouglalis, Eric Neveux and Larry Smith – for being so easy to get along with, and for taking part in a spirit of such mutual respect.

Our task was made a good deal easier, all the same, when the fourth day of our screenings came around and we saw Ida, the latest film by Pawel Pawlikowski. This austere, beautiful film, shot in gleaming black and white in the old 4:3 aspect ratio, won our collective hearts immediately. Agata Trzebuchowska plays a young, orphaned nun who is about to take her vows and renounce the world forever when a last-minute visit to her aunt changes everything. The film runs a lean, economical 80 minutes without a single wasted second: the performances of the two leads are flawless and the last few minutes incredibly moving, containing one image in particular which has been stamped on my memory ever since.

Unanimously we voted to give Ida the prize for best film. For our Special Jury Prize we chose Of Horses and Men, the debut film of Icelandic director Benedikt Erlingsson, which is truly something extraordinary. A series of short stories, essentially, about the relationships between the various members of a remote Icelandic community and their horses, this is by turns moving, hilarious, tender and savage. One scene caused several members of the audience to walk out while many of those who remained were convulsed with incredulous laughter. ‘Surreal’ was an adjective much used when discussing the film afterwards but I suspect that what we called surrealism was in fact merely the Icelandic version of reality.

One of the great things about the Les Arcs festival is that it’s not remotely elitist. Hundreds of members of the public from local towns and villages come to screenings of films from Bosnia, Italy, the UK and points in between. Among the films most enthusiastically received by the audience this year was We Are the Best, Lukas Moodysson’s comedy about teenage girls forming a punk band in 1980s Stockholm. Meanwhile, a more cerebral and chilling pleasure was afforded by Cannibal, a warped Spanish love story – very much reminiscent of Buñuel – with an outstanding performance by Antonio de la Torre as a respectable tailor from Granada with a nasty sideline in human flesh-eating.

At dinner on the first night, Pierre-Emmanuel Fleurantin talked to me passionately about the importance of the festival as a quintessentially European event, conceived to reaffirm the notion of a specifically European cinema at a time when the values of European cultural (and political) identity are being placed under unprecedented stress. And indeed, this was something that the festival triumphantly achieved. I came away from my week’s viewing thinking that I had seen twelve very diverse films, but also twelve films with something in common. Something hard to define, but which has to do with a shared aesthetic. None of these films were manipulative; none of them were propagandist. They evoked or imagined a reality and invited the audience to observe it, honestly, without judgment. Six out of the twelve films we saw had no background music and all of their stories seemed to be told through a camera whose gaze was cool but at the same time generous, fair-minded and even-handed.

Since my return from Les Arcs, most of the films I’ve seen have been American. The first one was American Hustle, by David O Russell, a director I’ve much admired in the past. And yes, I’m sure it was a fine movie. But I found it really hard to watch. Pawlikowski’s Ida was burned on my brain, its calm, lucid, unhectoring narrative strategy still acting as a kind of template. And here was an American movie bashing me over the head with its own cultural self-confidence, slapping 70s rock music over every scene to keep up the energy levels, the actors all giving loud, knowing, look-at-me, bigger-than-life ‘performances’, even the retro accuracy of the 1970s costumes and hairstyles giving off an air of self-congratulation.

I’ve had the same response to other American films I’ve watched since, even ones by fine auteurs like Soderbergh and Scorsese. Suddenly this feels to me like a cinema which is, at heart, much too pleased with itself, with its place in the world, with its right to command attention and its entitlement to a global audience. And yet nothing I’ve seen from America in the last couple of weeks has haunted or impressed me as much as, for instance, the wonderfully nuanced performance of Igor Samobor in Class Enemy, a Slovenian film about the quasi-fascistic methods of a German schoolteacher who drives one of his elite students to suicide. But will this powerful yet highly entertaining film – and many others like it - ever be shown in America or Western Europe outside the festival circuit?

Writing the introduction to my recent collection Marginal Notes, Doubtful Statements, I noticed that, of the writers, composers and film-makers I’d chosen to discuss, ‘many (if not most) … are outside the mainstream or the canon: they have been marginalised either by their gender, their aesthetic, by some awkwardness of temperament or even (from the British point of view) simply by having the bad manners to write in a language other than English’. In other words I realised, after putting these essays together, that I have always been drawn to figures who have been pushed to the cultural margins. Right now I sincerely hope that this category is not starting to include, by definition, all but a few of the most high-profile European film-makers. That would be a real tragedy.